This article has been previously published in Finnish with the title "Lohdutusten arkisto" (Ruukku 4, 2015), and develops the themes introduced in the essay "A videowork as a genre picture" (Ruukku 2, 2014).

25.10.2012

Today, at the kitchen table – as I was eating macaroni with Tilda – I figured out how to make the video about Hammershøi. In other words, I now know what I want to say with my work: I want to console the woman in black seen in the paintings.

How will this happen? I hear words, a variety of human voices, in my head. Words of consolation spoken in different languages. Whispers. Including babbling (Tilda).

I should start recording what Tilda says. The rest of the words of consolation I can collect at the NSU winter symposium.[1] I could give a presentation about Hammershøi and ask listeners to write to the woman in the paintings. Or perhaps I could get them to speak the words directly onto tape.

And what would pictures of consolation be like? They should at least contain light. In Hammershøi’s paintings the sky always seems to be cloudy, everything seen out of the windows is grey.

Rays of sunshine could appear amid the grey. Not a harsh, bright, spring sunshine that makes everything feel even more gloomy, but a soft, gentle light. The kind that filters through a thin covering of cloud.

What else? A candle. A slender white candle in a metal candlestick. On a windowsill or on a small, round table in front of a mirror.

And children’s voices in the background. Clear, insistent, selfish. The kind that know nothing of adult sorrows.

It makes no difference what the woman is grieving over, that is not the viewer’s business.

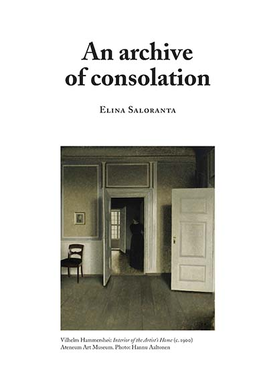

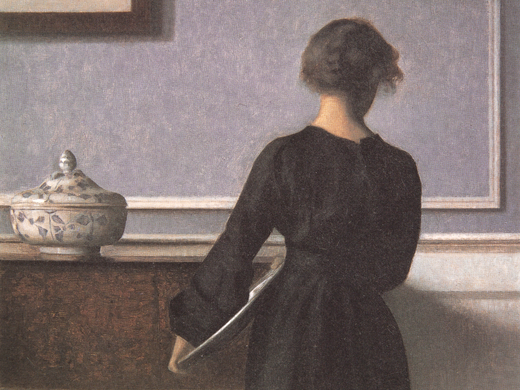

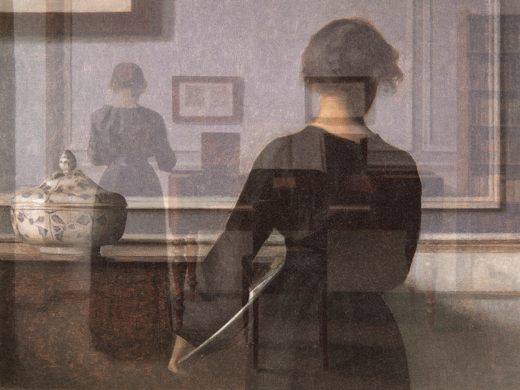

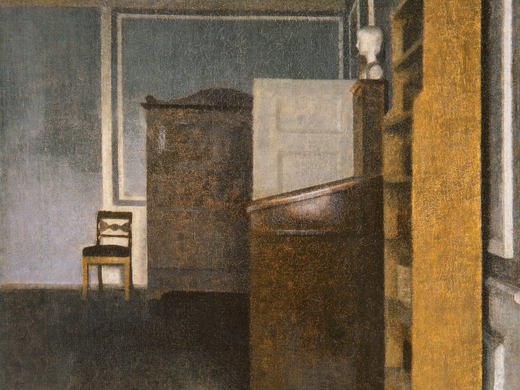

The above text describes the moment that my Voices of Consolation (2014) came into existence. The candle, my daughter Tilda’s babbling, and more children’s voices got left out during the process, but on cursory inspection the work keeps to the vision that I had at the dining table. The video’s image track consists of interiors – silent, half-empty rooms with white panel doors – by the Dane Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864–1916). On the soundtrack a group of people are trying to console the woman who wanders around in those rooms. She is Hammershøi’s wife Ida (1869–1949), but that is not relevant with regard to my work – the most important thing is that, on that October day, I was able to see her as a mirror for my own low spirits.

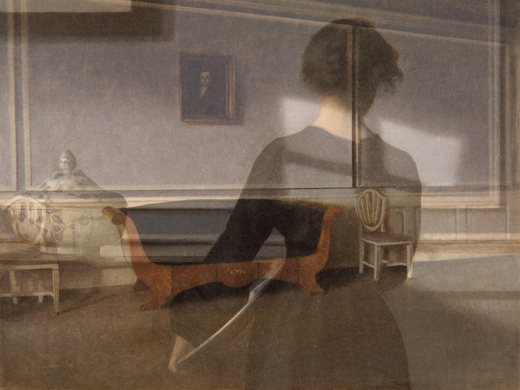

I carried on planning the work on the evening of the same day, after getting the children to sleep. Then, too, I was sitting at the kitchen table with a dog-eared postcard in front of me. The card was of Hammershøi’s painting Interior of the Artist’s Home (c. 1900), which is in the Ateneum Art Museum’s collection in Helsinki. The sequence of three rooms depicted in the painting is astonishingly reminiscent of the view that opened up before me from my place at the table, which I had also filmed on numerous occasions – the last time in the videowork Two rooms and a kitchen (2010). In my mind these two spaces slipped on top of one another. They began to be visible through each other like the double exposures or slow cross-dissolves that I love so much. Hammershøi’s Danish Classicism was combined with 1920s Töölö [2] Neo-Classicism, a Biedermeier chair appeared beside the wall, and Ida’s black back took up position in the doorway. The experience made an impression on me: this was the first time that the same sort of thing happened to me while I was writing as happens when I am making art. I realized that the way I construct images had already become a way of thinking, and that my diary entries were beginning to resemble my videoworks.

Could a structure like this work in a research text, too? Let’s see. My research is linked to the interaction between image, word and sound (or voice), and to the greatest extent that is what experiments in writing are. Added to that, my research is already in its final stage, so it is only natural that the artistic strategies begin to be visible on the level of the text, too.

Let’s imagine that my essay is a house in which there are several different rooms. As I am writing, I go (in slow dissolves) from one space to another. A moment ago, I was in the kitchen. Now, I am moving to the dining room. This is in Hammershøi’s home country of Denmark, where the Nordic Summer University (NSU) gathered in July 2012. So, chronologically, I have gone back a few months from when I was eating macaroni with my daughter. This time, I am having coffee with some colleagues. I have just given a presentation of my work and we are talking about something that someone came up with at the end of it: my videos remind them of the paintings by the Dutch artist Jan Vermeer (1632–1675). This was an important conjecture; I realized that I am at heart a genre painter and that the context of my works is not video or film, but painting.[3] I suddenly remember hearing about an artist who has been dubbed “the Danish Vermeer”. I don’t know his name, but everyone understands who I mean. When coffee break has ended, I go over to a computer to Google. Hammershøi’s paintings spread out in front of me like film frames. Dozens of ‘takes’ of the same rooms.

This was my first encounter with Hammershøi. Or, at least, that’s what I thought – later on, I realized that there was one of his paintings in the Ateneum, and that I had already long since bought a postcard of it. I remembered that I had also seen one of Hammershøi’s works in the Aarhus Art Museum in 2011. The small-format, brown-toned interior had made a big impression on me, even if I had not made a mental note of its maker.

There was thus already a strong connection between Hammershøi and me even before I became aware of it. Having realized this, I thought of writing about it, but the filmic quality of the paintings tempted me to take a look at what kind of video would come out of them. It was just that I didn’t know what I wanted to say with the work, until I noticed I identified with Ida. At first, I thought of adding views of my own home to the paintings in the way that I had outlined in my work diary. The aim was to parallel two times, two artists’ homes, and two women, so that it would not be entirely clear who is being consoled here. Later on, I decided to limit the material to Hammershøi’s works, but I still managed to begin the shooting sessions, and I will be returning to them again in my writing. Before that, I will pay a visit to the cellar of our textual house. There is a low, windowless room there, its floor covered by a brown wall-to-wall carpet. It was in this room that I recorded the consoling voices in February 2013.

THE CELLAR

The room is actually in the basement of the Iceland Academy of Arts in Reykjavik. It is a small, intimate seminar space, where a winter symposium of the NSU’s artistic-research study circle is going on. As a recording studio the space is nothing special, since it has fluorescent lights and mechanical air-conditioning. The lights buzz so badly that they have to be switched off. The air-conditioning cannot be turned off, so it will have to represent the hum of the wind or the murmur of blood circulation.

The participants sit at the back of the room on chairs arranged into a semicircle. They are artists and researchers from different disciplines, some of whom are working on their doctoral theses, while others are simply interested in artistic research. This last aspect is important: in this community artistic research comes across as one way of making art. Also important for the success of my own work is the fact that among them are numerous representatives of the performing arts – they are used to all sorts of ‘lab work’ or playing together.

The microphone is positioned in front of the participants in the light of a small table lamp. Leaning against its stand is a postcard, the same one that lay on my kitchen table at the start of this essay. Before beginning the recordings, I show the people some other paintings by Hammershøi and tell them who the woman who appears in the pictures is. I say that the woman’s identity does not matter, in any case, and everyone can think of who they want. My only hope is that the consolers will use their own mother tongue or some other language that they know well, not just English. I also ask them to repeat their lines a couple of times, so that I can adjust the sound level, if necessary.

One at a time people get up and step in front of the microphone. I stand behind it with earphones on. I look each of them in the eye and give them the signal to start. There is something of the ritual, something almost religious, about the situation. The room’s underground location, the darkness and the buzzing make their own contribution.

Initially, we go in seating order. The first in the row hums. The second carries on with singing. I don’t understand the words of the song, but I am told that it is a love poem by the Icelander Rósa Guðmundsdóttir (1795–1855). The third whispers: “Are you okay? Are you okay, Elina?”

The next eight alternately whisper and sing. The songs are lullabies: the English-language Mocking Bird is followed by the Finnish Nuku, nuku nurmilintu (Sleep, sleep little bird), and even a song from Tuva, performed by a Danish woman who had spent time in Siberia. The whispers are in Icelandic, French, English and Danish. They offer assurances that Ida has no need to fear, that all is well. One reminds Ida that she loves her and urges her to take good care of herself. But what moves me most is the phrase: “You are so much more than this.” It not only consoles, but also challenges.

The twelfth consoler says nothing, but tries to touch Ida. In practice she strokes her own arm close to the microphone. The next one lets out the quiet shush from between her teeth that she normally uses to soothe her own child. Another, slightly older woman sitting beside the young mother says that time heals all wounds. Then, one critical participant has had enough and shouts: “Now it’s time to scream!” I ask her whether she would like to do this, but she declines. The next person in the row does not raise her voice either, but whispers quietly in Greek: “Speak to me, speak to me…” Finally, a Danish actor gets up from the row of seats and urges me to cover my ears. I turn the sound level down. The scream, nevertheless, is so badly ‘distorted’ that it is technically unusable. But psychologically the cry does its job. People burst out laughing, and from this point on there is space in the room for voices other than gentle ones.

The change is not immediately visible. Maternal words, stroking that avoids ruffling the fur, can still be heard: “I know, I know, it will be okay. It’s going to be okay…” and “I don’t know what to say. I’m so sorry…” Then, one of the consolers gives a long monologue, in which we can sense a mild irritation. He speaks Norwegian, but I understand that he is trying to coax Ida to go for a walk. The man’s Danish companion in the next seat joins in and reminds us that the sun is shining outside.

There are three other Finns in the group, apart from me, the first of whom has already performed. Now, it is another one’s turn. “Hi there…” she says in Finnish, “Only you give yourself value.” The words are true, but for some reason to me they seem bland, embarrassing even. Of course, I don’t reveal my reaction, but say that we need some more short lines to counterbalance the lullabies. “Life isn’t fair…” the next in the row says, “We know that, but it doesn’t make it any easier.” The phrase is in no way any more original than the previous one, but it is easier to put up with it in English. And it is even easier when you don’t understand the language at all: for example, to my ears the Polish translation of the Russian Alexander Pushkin’s (1799–1837) poem sounds exotic, and has me admiring ‘Slavic sentimentality’. In contrast, my third compatriot’s adage: “You’ll be alright. The sun shines on a pile of twigs, too…” makes my cheeks burn red with shame.

We have now been round everyone once, but I ask whether anyone still wants to say anything. A few of those who performed earlier volunteer. Once again they try to tempt Ida to go for a walk and, in addition to Pushkin, there is also a quotation from the Dane Karen Blixen (1885–1962). People become keen to use new languages, too: a Norwegian starts speaking Hungarian, a Greek Portuguese, and an Irishman, who previously spoke English, Irish Gaelic.

Suddenly, one of the ones who, earlier on, addressed Ida in a maternal manner walks boldly up to the microphone and blurts out: “Seriously, he is a fucking idiot. You’ll get over it.” The whole room bursts out laughing. It is like a continuation of the laughter that had its beginnings in the scream, but, now, we howl with tears in our eyes, and the outburst feels like it will never end. A Danish philosopher observing the situation – the only one who did not want to share in the consolation – urges me to keep the laughter on the final soundtrack.

When the laughter has abated, the Icelander who sang Guðmundsdóttir’s love song at the start gives a speech to Ida. It is in Icelandic, but someone interprets it for me: “Dear Ida, all these people have tried to console you, and you just turn your back… You have to look at us!” I am already seeing in my mind how Ida turns towards the viewer of my video at this point, we may even see her in close-up.

A few people still want to try their luck. We get to hear more ‘Slavic sentimentality’ and Scandinavian sighs. The last consoler, nevertheless, refuses to sigh, and shouts lustily in Swedish: “Hello, hello, I’m home! Where are you?”[4]

Before we go back out into the daylight, I, too, stand in front of the microphone and utter my own words of consolation: “It’s alright, everything’s fine, everything’s fine…”[5] This is the mantra that I am in the habit of repeating to my daughter when she cries. For a moment, Ida’s name is actually Tilda.

THE KITCHEN

I have described the recording situation very precisely for two reasons. In the first place, I have wanted to foreground the fact that the soundtrack came about as a group effort, as the result of a kind of group dynamic. The recordings were not made one at a time in a soundproofed booth, but rather the participants were in the same place the whole time. They heard each other’s lines and reacted to them. That is why a certain dramatic quality already began to be built into the work in the recording situation. It started off gentle and witty, fractured at the point of the scream, and then ultimately broke down when fucking idiot entered the picture, and softened once again towards the end. “Hello, I’m home!”, however, is gentle in a different way from the initial whispers. It is not a sublime cry, but a commonplace, outright cheery one, which prompts us to ask whether things are ultimately as bad as we imagined.

In the second place, I am interested in the relationship between the finished work and the raw material. What choices did I make when I was doing the editing, and how did the pictures influence the voices? But, before I can consider these matters, I have to create an overview of the work’s pictorial world. I will begin by returning for a moment to the shooting sessions that I did in my home when I was starting the work. If my essay is a house, I am now stepping back into the kitchen. Winter has turned to spring, and the room is flooded with light. The camera stands on a tripod in front of the sink unit. I have set it up there many times before, but now the legs are adjusted to be longer than usual, at the same height as Hammershøi’s painting easel. On top of the camera is a yellow spirit level bought from a hardware store. It is a tool to which I have become downright addicted – it irritates me enormously if the door frames are not straight!

There is all sorts of stuff lying around on the floor – electrical leads and toys – but on the camera’s viewing screen the apartment looks almost empty. The wide-angle lens and the numerous doors also make it look more spacious than it really is, instead of a flat with two rooms and a kitchen, we could be in a large, bourgeois home. At the back of the last room is a bookshelf, its glass doors reflecting the light. This brings to mind the small-paned interior window that recurs in Hammershøi’s paintings. In the centremost room no furniture can be seen other than a small, round table, the same kind that Ida has. Above the table – where Hammershøi would have hung a framed picture – is a rectangular mirror, in which a patch of sky is reflected.

I place a candle on the table and press the “REC” button.

Stop. The candle looks pathetically small in the wide-angle image, and the sky is burnt out. I take the candle away, and draw the thin white curtains in front of the window. This creates a Hammershøi-esque haze, the feel of a cloudy day.

New take. The outlines of the mirror are delineated beautifully now that the overexposed sky no longer seeps over the edges. The shape is repeated in the door panels and in the glass panes of the bookshelf. But what is that mess over there? Behind the glass we can make out some storage boxes and a few photographs.

Pause. I wonder how much stuff would have to be got rid of for the picture to become a ‘Hammershøi’. The aim is not to aestheticize, but to abstract – just as Hammershøi abstracted his home by emptying it of furniture and turning Ida’s back to us.

I remove two boxes from the bookshelf. They are too recognizable – IKEA. At the same time, I turn one photograph round so that the model’s face becomes visible. A picture within a picture, Hammershøi pulled tricks like this. The Finnish painter Paul Osipow thinks he used them to drum up applause from the public.[6]

I hear how I, too, receive applause. The applause is, nevertheless, mingled with boos: You’ve done this already, why are you repeating yourself? I maintain vocal silence and carry on the filming sessions for a few more days, but I no longer find within myself the motivation that I had before. Not even the sun of approaching night, which normally gives me inspiration, helps. In the end, I give in and decide to limit the pictorial material in my work to Hammershøi’s paintings.

Even if these shooting sessions failed, they have research significance, since they say something about my relationship with Hammershøi – about the way I have conducted a dialogue with him. This has not happened solely with the aid of literature, but also by moving objects around and by pulling the curtains in front of the window. Isn’t this artistic research at its best? I can’t help also thinking about the investigations that artists of former times carried out when they copied the old masters.

Copying makes it possible to acquire a lot of information, and I believe that I, too, realized something fundamental about Hammershøi when I tried to copy him. Above all, I realized that you can’t view his works through melancholy alone. The emptiness of his rooms is not a sign that something is missing – he simply happened to be someone who was fascinated more by walls than by furniture. The greyness of his palette is not colourlessness, but an interest in a certain, limited colour scale. His model does not have her back to us because he wanted to repel us, but to make it easier for us to identify with her.

There is plentiful support for my insights in the Hammershøi literature. For example, the Swede Görel Cavalli-Björkman warns against psychologizing Hammershøi’s works, and reminds us that the artist was primarily interested in aesthetic questions.[7] Osipow and the Swede Ola Billgren go even further in the correspondence they conducted about Hammershøi’s works in the 1990s.[8] On listening to these men, Hammershøi comes across as an abstract painter whose passion was the geometric shapes of doors, windows and wall panels.

This affinity for geometry can go so far that the impression becomes too neat and meticulous. Billgren uses the word “sterile” to refer to Hammershøi’s rooms and, at the same time, hints at the couple’s childlessness.[9] Could this hygienicness, for its part, explain why it was impossible for me to connect my home to Hammershøi’s home? Perhaps the toys lying around on the floor were too much, perhaps too many storable items had accumulated on the bookshelf. It may also be that children’s voices were left out of the work for the same reason. Children don’t belong in Hammershøi’s world, not even in the background.

And yet, for me, Hammershøi’s rooms are not gloomy. On the contrary, they are just the kind of bare, stimulus-free spaces to which I would frequently like to withdraw in the midst of everyday life. For me, art in general is a kind of quiet room. I am able to take myself there by reading or looking at pictures, but also by directing my gaze at something impressive, for instance, the evening sun. One of the most important spaces to withdraw to is, of course, the studio.

THE STUDIO

The air-conditioning makes a noise and the lighting is dim. We can’t see outside from the narrow window, but into the adjacent entrance hall. We are again almost underground, in the depths of the former bread factory occupied by the doctoral programme of the University of the Arts Helsinki’s Academy of Fine Arts before the mould that had spread through the building forced it to move.

On the computer screen are images of Hammershøi’s paintings. I have reproed the pictures from books and cropped them so that the aspect ratio is 4:3. Now, if not before, the paintings look just like film stills. The feeling of committing a sin prompted by doing the cropping is alleviated by the knowledge that Hammershøi himself cropped his own compositions after they were completed.[10] So the edges of the pictures are not sacrosanct.

The majority of the pictures were painted at the Strandgade 30 address where the Hammershøis lived for ten years. It is surely no coincidence that the house was built in the 1600s, in the century of Hammershøi’s idol, Vermeer. In fact, the whole city district is reminiscent of a Dutch port city.[11] When the Hammershøis had to give up the apartment, they moved elsewhere for a few years, but then returned to Strandgade opposite their former home.[12] With artistic license, I give myself permission to combine paintings made in the different apartments as if they were views of the same location.

To start with, I choose about ten of the pictures, and place them one after another on a timeline. For the duration of each frame I enter 30 seconds. Then I add a long cross-dissolve at the cutting points. In practice two frames are now constantly overlaid and the image track is in continuous metamorphosis: just when a painting has become visible, another one begins to be glimpsed through it from beneath, a door opens up in a wall, a mirror turns into a window, a chair shifts position…

The next thing to go on the timeline is the recordings that I made in Reykjavik. The voices have not yet been edited in any way, they include all the repetitions, coughs, and the roars of laughter following fucking idiot. The first thing I remove is the repetition. Then, I censor all the most embarrassing words of consolation – a couple of Finnish ones and the one that mentions my name. A few are also left out for technical reasons, for example, the idea of touching does not come across solely with the aid of the sound.

Before starting the editing I have already decided to hold on to the dramatic quality that emerged in the recordings, but the multi-layeredness of the images has me wondering whether the voices might occasionally be superimposed on one another. And what if I were to choose from among the words of consolation a few that are to be repeated throughout the work?

I test this out by making a copy of the soundtrack and overlaying it with another. The speech is now mixed with humming, the whispering rises above the lullaby, the different languages can be heard through each other. And yet I am unable to let the voices carry me away, but rather I struggle to hear what the individual people are saying. I realize that I want to make each of the spoken lines distinct, even if I don’t understand their content. I want to focus on one voice at a time.

I thus decide to go back to the original plan and keep the voices separate. In my mind the work will be an archive of words of consolation. In an archive things have to be presented systematically and matter-of-factly, so that everyone can find what they need. Nor is an archive ranked in order of value, but, rather, all the material in it is equal. I even go so far as to put pauses of exactly equal duration between each of the spoken lines. Later on, I abandon such a mechanical approach, but a certain dryness – a cataloguing quality – is retained as the soundtrack’s editing principle.

Along with these thoughts the place for the voices also becomes clear. I realize that the voices don’t belong inside the images, but in front of them. I thus don’t try to create the impression that the words of consolation echo around the rooms, nor that those who utter them are in the same space as Ida. Instead, I think of the consolers as being in the same place as the viewer. They stand facing a two-dimensional surface – a display screen, a film-projection screen or a painting. They speak, sing and whisper to the pictures.

Pictures are mute, and that is why I don’t feel a need to have other voices in the work. The only exception is the line: “Hello, I’m home!” before which, in my mind I hear a door banging shut. I borrow the sound from my earlier work Room (2008), which shows the changes that occurred in a bedroom after the occupant of the room died. Viewers will very likely not notice where the sound comes from, but the researcher in me chuckles happily. The works are in fact clearly related to each other. Both consist of static interiors that change in slow cross-dissolves, and we could say that Room is my first genre picture – in the sense that interiors are heirs to the genre painting. The banging of the door is thus a small intertextual reference between two works that represent the same genre.

On the soundtrack the bang is accompanied by footsteps and the floor creaking, and, for a moment, I play with the idea that the sounds come from Ida’s movements. The idea is, nevertheless, absurd, since Ida does not get around by walking, but passes through walls like a ghost. Hammershøi’s paintings are already silent to begin with, and the surreptitiousness of the dissolves makes them even more soundless.

Now that the structure of the work is clear, I start looking for places for the individual images and spoken lines. In the case of the pictures I look at how door frames and wall panels coincide when two paintings are on top of one another. And yet I don’t try to achieve a perfect match, but, rather, I enjoy it when the lines are multiplied and a translucent grid forms on the picture’s surface. If a door frame is skewed, I straighten it, but otherwise I don’t manipulate the images.

With the voices I try to ensure that different languages are distributed evenly and that there is always a phrase in English at suitable intervals. I don’t want to subtitle the work, but I hope viewers will grasp the idea of it from slight hints. By leaving the words untranslated I also try to conceal how time-worn they are and to direct attention to the colours and cadences of the voices.

Originally, I was going to start the video with Interior of the Artist’s Home, which is in the Ateneum’s collection; after all, it was one of the work’s starting points. But the picture does not seem to fit the beginning, since Ida is barely noticeable in it – she is just a dark figure beside a wall. Instead Interior, Strandgade 30 (1908), which I saw in Aarhus, is as if it were made for the introduction. In it Ida sits in the foreground of the picture with her back to the viewer. The room is the same one as in the work in the Ateneum, we even see the same chair and framed picture there. If we think of the paintings as film frames, they could be from the same scene – a careless photography assistant has just gone and switched the pictures between shots.

This pair of images becomes the establishing shot for my video, the initial image that introduces the story’s location and main character. During the scene, Ida gets up and starts to move around. The rest is constructed like a long tracking shot. The camera stays behind Ida’s back and follows her wanderings around the labyrinthine space. Sometimes Ida disappears from view, sometimes we find her sitting at the table or the piano. In the second-to-last image we return to the same space as we began with. Ida is sitting there reading and, for the first time, we see her from diagonally in front. An insistent woman’s voice demands that she turn even more and look towards us. Unlike how I imagined it in the recording session, Ida does not obey. She doesn’t even appear all that downcast. Then the doors of the room open, and Ida evaporates into the air. All that remains is an empty space and the question: “Where are you?”

Apart from that last line the words do not seem to require to be paired with any particular picture. That is why I mainly edit the soundtrack and image track separately, seeking each one’s own inner rhythm. I try to avoid illustration, but in one instance I make an exception: when it says on the soundtrack that the sun is shining outside, a paned-window-shaped patch of sunlight appears on the wall of the room. I don’t need to film this myself, since the patch is there in Hammershøi’s painting Sunshine in the Drawing Room III (1903), right beside the Empire sofa. The sofa having disappeared, the sun is left to warm the back of Ida’s neck in Interior with Young Woman from Behind (1904). As if this were not enough, the next consoler reinforces the words of the previous one: “Look, the sun is shining… I know you don’t see it, but I want you to feel it.”

Why on earth would I want to create a situation in which voice and image don’t just illustrate, but also outright underline each other? I don’t know. Perhaps this was one attempt to subvert the banality of the words, to turn it into something self-conscious. Or perhaps it was just fun for me to go along with the speakers’ wishes, to put the sun there shining at precisely the moment they were uttering their words. That underlining can also be a reading instruction, a way of saying that, in this work, things are as they are said to be. Viewers do not need to look for hidden meanings, the work does not try to symbolize anything.

The power of the patch of sunlight is, nevertheless, based on it being an exception to the rules. Elsewhere the images appear to be indifferent to the words; they change at their own pace regardless of what is happening on the soundtrack. Not even fucking idiot makes Ida jump; she just sits motionless at the piano (and doesn’t play).

I, in contrast, jump every time I hear those words. I experience that, at that moment, time is ruptured and the start of the 20th century becomes the start of the 21st, a refined genre picture becomes coarse contemporary art.

In the recording situation that rupture was followed by a concrete eruption, an outburst of laughter. What were we laughing at then? Not perhaps the rift in time, since deep underground in that windowless seminar room we were outside of time. By that I mean that we were in an interior world, in a place where the different centuries can perfectly well exist simultaneously. Before fucking idiot, however, we had lulled ourselves into a certain mood. We had got used to the whispers and the lullabies, and even if the scream had already shaken us up, nobody could have expected anything so gross – especially when this was about a Danish national hero, a restrained, well-liked man.

Fucking idiot was thus a rupture in the register, in the mode of speech, and the outburst of laughter was its physical manifestation, a sound that derives from something breaking. Pop. Crackle. Bang! No wonder I was told to keep the laughter on the soundtrack. It was like a breath of fresh air in a room that had gone stale. But at the editing table, faced with the image, that giggling no longer feels refreshing, rather, it brings to mind those pre-recorded laugh tracks on television.

I edit out the laughter. Left in its place is a silence, which viewers can fill with their own reactions. After the pause, I insert the Tuvan lullaby. This is the most visible change that I make to the original, to the drama that took shape in the recording situation – the majority of the lines spoken are so uniform in tone that moving them from one place to another doesn’t change the structure of the soundtrack.

If I had to choose one sentence that I’d like viewers to remember from the archive of words of consolation, it would be: “You are so much more than this”. That’s why I am putting it second to last, just before Ida evaporates into the air, and the furniture along with her.

The last line spoken is not actually words of consolation, but a rhetorical question. Some might experience it as being said by Ida after she has returned home. I, nevertheless, think that Ida leaves forever, and the question is asked by someone else – perhaps Vilhelm, who opens the door unsuspecting that the apartment is empty. Admittedly, the voice is that of a woman, but in art little things like that don’t matter… In any case the question goes unanswered, and viewers will have to answer it themselves. Or perhaps the answer will come in a future work, perhaps Ida will still burst into speech.

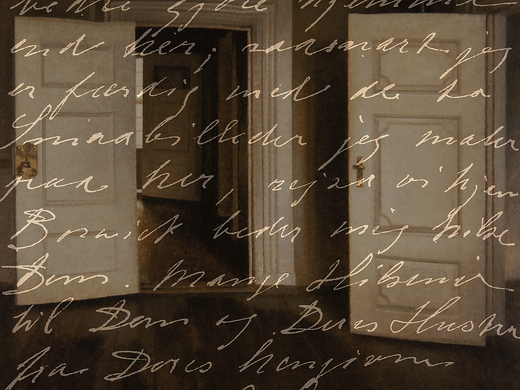

THE LIBRARY

Before the video is finished, we need one more transition. This takes us to the University of Helsinki’s library to look for a picture of Hammershøi’s handwriting – I would like to use it behind the opening and closing credits. I have already been through the library’s Hammershøi collection several times, but there is one work on the shelf that I have previously overlooked. It is Sophus Michaëlis and Alfred Bramsen’s Danish-language Vilhelm Hammershøi. Kunstneren og hans Værk from 1918. I open the book at random. Between the pages is a thin, pale-blue sheet of paper with something written on it in an ornate hand. I initially think it is a slip of notepaper, but I soon realize that it is part of the book – an authentic-looking reproduction of a letter written by Hammershøi! The letter is addressed to Bramsen, but I am sure that it is ultimately intended for me. It is a personal message from Hammershøi, a sky-blue letter from the dead.

I borrow the book and take it a few blocks away to graphic designer Jorma Hinkka’s studio. Hinkka has created the opening and closing credits for almost all my videoworks, and even if the credits can appear to be only a minor detail, they are an important part of the whole – after all, in its own way typography is a dialogue between image and word.

Hinkka photographs the letter and crops it to a suitable shape. We have to give up the pale-blue background at this point, as it doesn’t go with the images. In the finished work the background to the letter is black and the handwriting golden yellow. The shade has been picked out of the golden-framed picture at the start of the video.

The title and the closing credits in pure white stand out from the handwriting. The typeface is called Auto. It is ‘grotesque’, i.e. the strokes are all of uniform width and none of the letters have serifs on the ends of strokes. That is why it works well on video. In their proportions the letters are, nevertheless, reminiscent of Antiqua serif lettering, which has its roots in ancient Rome. The overall impression is classical in a similar way to Hammershøi’s paintings.

The texts also change in the same way as the pictures do, with a cross-dissolve. At the beginning, the title disappears from the frame before the background does, so that all that remains is the handwriting. The first picture rises on top of it, or actually behind it, since the words appear to hang in the air in front of the space of the room. They are like a curtain through which the work is viewed. And because the script is calligraphic, that curtain has to be lace. (I doubt that Hammershøi would have been overjoyed about this association, but Ida would surely have understood me.)

As the work ends, the curtain of text again appears over the image. Now, I see it as a front-of-stage curtain, which closes after the film finishes. The audio equivalent of the stage curtain is, of course, the signature tune, in this case the humming that is repeated at the beginning and end.

The credits give the participants’ names, but also say how the work was made: “The voices were recorded in the Nordic Summer University’s study circle on artistic research in 2013. I showed the participants a painting by Vilhelm Hammershøi (Interior of the Artist’s Home, c.1900) and asked them to console the woman in it.” The way the text is formulated brings to mind a new, and perhaps surprizing context – idea-based conceptual art. The work could be used as a basis for creating a recipe that would be repeatable anywhere, even ‘live’ in museums. It could be a Fluxus-type instruction piece: Choose the picture that you would like to console, and sing to it…

At the end, I indicate where the images in the video come from: “The images are of Hammershøi’s paintings and have been photographed from the following books…” There are only three sources, and they were not chosen for their academic legitimacy, but for their printed impression. The details of the books have, nevertheless, been given with academic piety, in the same way as in research texts. With this gesture I want to compare the pictures in the work to citations. I think: I will cite Hammershøi by borrowing video-screen-shaped items from his paintings. Because I had no possibility of filming the originals, I had to resort to second-hand sources: art books.

One of those sources, Ordrupgaard Museum’s exhibition catalogue Hammershøi > Dreyer; The Magic of Images (2006), is visually particularly interesting, since it compares Hammershøi’s paintings to the films of the Dane Carl Theodor Dreyer (1889–1968). Dreyer himself said in an interview that his first film, The President (1918), was inspired by Hammershøi, and it is easy to see the original models in his later films, too.[13] So, I am not the only maker of moving images to notice Hammershøi’s filmic quality.

In my case, this observation was undoubtedly influenced by the fact that I got to know Hammershøi by Googling. It is possible that my work would not have come about at all without this banal detail, since online the paintings burst out in front of me in the readymade form of a film strip, serially.

Annette Rosenvold Hvidt, the editor of the Ordrupgaard exhibition catalogue, conjectures that Dreyer, too, may have seen Hammershøi’s paintings in reproduction. In real life on the surface of the paintings there is, in fact, something that Hvidt calls tar.[14] I would describe this as meaning that, if Hammershøi were a camera, then there would be a soft-focus filter (or a piece of pantyhose fabric) over the lens. Reproduction reduces the works’ ‘tarriness’ and makes them more graphic. This applies particularly to the black-and-white prints that were available in Dreyer’s time, but also to the low-resolution digital images that I saw online. In a way Hammershøi’s paintings are more filmic the more rudimentarily or the more poorly they are reproduced!

Hammershøi was not a camera, but in some respects he acted like one. His contemporaries already noticed this: it was said that Hammershøi’s painting style resembled the mechanical objectiveness of the camera, and that his works could be replaced by photographs.[15] Subsequently, researchers have tried to trace the origins of this ‘objectivity’. There has been speculation about the extent to which Hammershøi painted from photographs, or about whether he used optical aids, such as a camera obscura.[16] From an artist’s viewpoint, the discussion of aids is always a bit troubling, but Billgren (himself a painter) brings a fresh viewpoint to this: at the turn of the century, Hammershøi was in no way the only artist to resort to photography, but unlike the others, he let it be visible![17] Also intriguing is the Dane Gertrude Oelsner’s idea that Hammershøi had a ‘photographic eye’, a way of seeing the world that was shaped by photography.[18]

There are even templates for Ida in the history of photography. One of these is an 1856 portrait of Marie Laurent by the Frenchman Félix Nadar (1821–1910). In the picture Laurent is seen from behind with her hair up and her body wrapped in a sculptural cloth, which accentuates the soft, white skin of her neck. Hvidt links this mode of depiction to ideas of the unconscious – the neck is the subliminal side of the face.[19]

At the beginning of this section, I got a letter from Hammershøi, but, of course, it would have been even more exciting to get a letter from Ida. Some letters from her have, in fact, been preserved, and on the basis of these the Dane Poul Vad describes her as a good wife, although “touchingly naïve” as a human being. It is also known that Ida suffered from “attacks” of the same kind as her mother did. During them, Ida undoubtedly longed for consolation, but were the attacks really the “desperate cries for help” of a woman condemned to a bourgeois marriage, as Vad thinks?[20] Or did Ida inherit migraine from her mother as I did?

On the day that I wanted to console Ida, I myself was in need of consolation. I found solace in Hammershøi’s paintings, in their cool, quiet rooms. The best thing was that in those spaces I did not have to pretend to be in a good mood. Herein lies the power of art, its capacity to console. As the philosophers Alain de Botton and John Armstrong say, art “does not deny our troubles; it doesn’t tell us to cheer up.” Instead, art reminds us that sorrow is normal and universal, it “is written into the contract of life.” The worst thing is to be left alone in our suffering.[21] In Hammershøi’s rooms we don’t have to be alone, Ida is there.

IN CONCLUSION

At the start of my essay I asked whether a research text could be constructed like a picture, and I said: “Let’s see.” Now, it is time to look at the results of that experiment. What does it look like, is the house still standing? The reader is better able to answer that than I am, but what I can say is that the writing was not easy. I often had the feeling that I am not capable, that I need help, perhaps even consolation...

Now, in retrospect, I can console myself with the fact that the task was a demanding one. I tried to translate my language of artistic expression into another language, into writing. Or was I trying to turn writing into pictures? In any case, I moved ever closer to literary expression, which has been drawing me to it for a long time, but which poses greater technical challenges than an informational text.

Now that I have used the word “literary”, I have to point out that I don’t imagine that I have created anything new in terms of experimental literature. I know that, for example, the Frenchman Georges Perec (1936–1982) has written an entire novel with chapters corresponding to the rooms of an apartment block (Life a User's Manual, 1978). No, my essay is an experiment in terms of my own production and the tradition of academic writing. Instead of Perec, my role models are practitioners of autoethnographic research, who in their texts have used diary extracts and evocative description.[22]

Penning descriptions is still relatively unproblematic, but how do I write dissolves? This was the biggest technical challenge in my experiment, and I don’t yet know whether I succeeded in this. What in general could be the textual counterpart to a cross-dissolve?

In the language of film dissolves generally refer to the passage of time, but when the fades are long enough, the images in practice become double exposures. At least, that is what happens in Voices of Consolation, in which two paintings are constantly superimposed on each other. In a text this could mean that the whole thing had several levels, which were not separated by clear boundaries, by straight cuts.

Dissolves are thus not necessarily transitions in time. They can also stand for the existence of multiple layers. Or they can be linked to the tone of the text, to how light or airy the narration is. Or do the dissolves only arise during the reading experience, when the mental images evoked by the text start to be glimpsed through each other?

In this experiment, however, the dissolves were only a mental game, around which I drew parentheses. Of much greater importance were the rooms, the way that the text was constructed like a house. Underlying this idea, of course, were my videoworks, but I suspect I would have come up with it anyway. The point is that art does not come about in a void, but in concrete spaces and situations. When I start writing, I go back to those places in my imagination. I see the walls, ceiling and floor of the seminar room. I hear the buzz of the air-conditioning and the comments uttered semi-casually. Those aspects do not necessarily end up in the text, but they do help to recall things to mind.

The ultimate motivation for the experiment was, thus, a desire to write as my mind works. To find a rhythm and a structure that serve recollection.

If the character of my text had to be summed up in a single sentence, it would be the question that I ask myself at the start of this essay, after I have realized that I want to console Ida: “How will this happen?” Thus, I don’t ask why Ida should be consoled, but rather how that could be done. Nor do I stop to consider the reasons for my own melancholy. That doesn’t interest me, I prefer to wonder how the feeling could be utilized artistically, what form could be given to it.

That sentence reflects the questions posed in my research more broadly. My work does not focus on abstract “why” questions, but rather its interrogatory word is the practical “how”. In the field of artistic research I am one of those for whom researching means making and the end results, too, are preferably artworks. The background to this is the idea that art itself is like research. It simply has to be made visible, and at best it succeeds by describing the processes involved in making the works.

Voices of Consolation is one of the end results of my research. It is a context made flesh, a consequence of my having realized that I am fundamentally a genre painter. It is an answer to the question of how to give research the form of art.

“An Archive of Consolation” answers the same question in its own way. It is an attempt to describe the process by which an artwork comes about so that the structure of the text reflects the structure of the work.

This essay does not, however, stop at description alone, since it not only tells how Voices of Consolation came about, but also demonstrates it in practice. It even does this in the authentic locations, the artist’s home and the university. At the university it takes readers down to the cellar and shows them where the microphone stood when the words of consolation were recorded. In the artist’s home it shows how the space is turned into a ‘Hammershøi’. This is my experiment’s most surprizing discovery: from the reader’s viewpoint the text serves as an illustrative demonstration.

Sources

Armstrong, John & de Botton, Alain (2013) Art as Therapy. London: Phaidon Press.

Berman, Patricia G. (2007) In Another Light. Danish Painting in the Nineteenth Century. London: Thames & Hudson.

Billgren, Ola & Osipow, Paul (2015) “Hammershøi”. In Timo Valjakka & Susanna Luojus (ed.) Hammershøi. Hiljaisuuden maalari. Stillhetens målare, 27–106. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society.

Bramsen, Alfred & Michaëlis, Sophus (1918) Vilhelm Hammershøi. Kunstneren og hans Værk. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

Cavalli-Björkman, Görel (1999) “Såsom i en spegel. Vilhelm Hammershøi och det holländska interiörmåleriet”. In Lena Boëthius & Görel Cavalli-Björkman (ed.) Vilhelm Hammershøi, 20–25. Stockholm: Nationalmuseum.

Fonsmark, Anne-Birgitte (2006) “Hammershøi > Dreyer. The Magic of Images. The Link from a Painter to a Filmmaker”. In Annette Rosenvold Hvidt (ed.) Hammershøi > Dreyer. The Magic of Images, 11–26. Copenhagen: Ordrupgaard.

Hvidt, Annette Rosenvold (2006) “The Strange Thing about Hammershøi”. In Annette Rosenvold Hvidt (ed.) Hammershøi > Dreyer. The Magic of Images, 43–62. Copenhagen: Ordrupgaard.

Vad, Poul (1992) Vilhelm Hammershøi and Danish Art at the Turn of the Century. Translation Kenneth Tindall. New Haven: Yale University Press. Danish original 1988.

Notes

[1] NSU stands for Nordic Summer University (Nordisk sommaruniversitet). I have been part of the NSU’s artistic-research study circle since 2010, and apart from Voices of Consolation I have made the videowork Reflections in a window pane (2012) there.

[2] Töölö is a district of Helsinki.

[3] In art history the term “genre painting” refers to paintings of everyday life, and I see my videoworks as kinds of present-day genre paintings. I have written more about this in my essay “A videowork as a genre picture” (Ruukku 2, 2014).

[4] “Hallå, hallå, jag är hemma. Var är du?”

[5] “Ei mitään hätää, kaikki on hyvin, kaikki on hyvin…”

[6] Billgren & Osipow 2015, 38.

[7] Cavalli-Björkman 1999, 21.

[8] Billgren and Osipow’s correspondence (Hammershøi) appeared in English in 1995 published by the Danish Bløndal. In 2015, it was published in Finnish and Swedish in Hiljaisuuden maalari. Stillhetens målare (Finnish Literature Society).

[9] Billgren & Osipow 2015, 83.

[10] Vad 1992, 366.

[11] Vad 1992, 181.

[12] Vad 1992, 318.

[13] Fonsmark 2006, 12.

[14] Hvidt 2006, 52.

[15] Vad 1992, 369.

[16] Berman 2007, 233.

[17] Billgren & Osipow 2015, 92–93.

[18] Berman 2007, 233.

[19] Hvidt 2006, 58.

[20] Vad 1992, 98.

[21] Armstrong & de Botton 2013, 26.

[22] Autoethnography is a branch of ethnographic research in which researchers also seek to personalize the research and include themselves. In practice they may make personal field notes or otherwise write in ways that open up their own experience. [Uotinen, Johanna (2010) “Kokemuksia autoetnografiasta”. In Jyrki Pöysä, Helmi Järviluoma and Sinikka Vakimo (ed.) Vaeltavat metodit. Joensuu: Suomen Kansantietouden Tutkijain Seura, 178–189.] I have written about my relationship with autoethnography in my essay "Hienopesu 40 astetta" (“Delicate wash 40 degrees”) published in Lähikuva 3/2013.

Translation: Michael Garner