Objective with this program:

The School Choir Advancement Programme aims to empower school choirs to further enhance their choral programmes and provide choristers with an inspiring choral education experience by working closely with overseas renowned conductors. The Programme also aims to provide the music teachers of participating schools with high-level professional development opportunities.

Together we developed strategies primarily for how to communicate with each other during the mentoring period, until the end of June 2025. The program is aimed at three selected teachers from primary school and four from secondary school. My colleague from Malaysia – Susanna Saw – is in charge of primary school and I take care of secondary school. We collaborate with local mentors who stay in regular contact with our mentees.

We – the overseas mentors - will engage with the choirs’ conductors on a regular basis, ideally conferring online once every two weekly rehearsals. These sessions will delve into detailed planning for upcoming rehearsals, score analysis, and rehearsal techniques. We will continuously assess rehearsal effectiveness by reviewing video recordings provided by the conductor.

After a commencement workshop with all school choirs involved, I and the local mentor conducted an initial visit to each participating school. We worked closely with the choir, observing and identifying specific development areas for the mentor, and establishing the goals for the upcoming year.

My first mentee

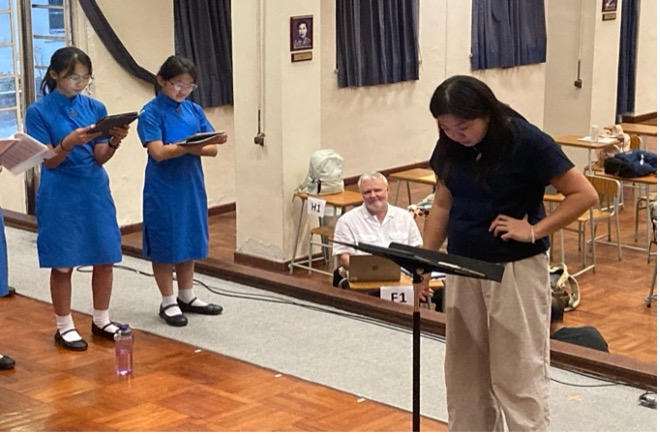

After a lunch meeting, it was off to meet my first mentee at the Heep Yunn School, a school for girls I was already well acquainted with after my project with the older girls' choir there in March. It was a true pleasure to meet the girls in the choir again and their skilled music teachers. We talked for half an hour about expectations for the program, the mentees' own wishes for professional development areas. This was followed by the observation of regular choir practice.

Meeting music teachers - conducting class:

After this first exciting meeting with my first mentee, it was on to a new conducting class, this time with beginners. It is still about music teachers, but who have not received much training in choir conducting in their studies. The average age here was also somewhat lower than in the previous group. In addition to focusing on conducting technical aspects, the commission for me was also about the choir director's role for the children in the school choir.

The first exercise I did with them was to stand along the walls – against the wall with eyes closed – and listen to a beautiful piece I played on the speaker system. Here it was about moving to the music completely freely with your arms – let the music define you, submit to the music. This reflects my philosophy – that in order to acquire the right to define the music, you must first learn to submit to the music. For some, this is a very challenging exercise. It's about letting go of your own control, allowing yourself to be engulfed by the music. It's also diffult for some not to move their arms in a pre-conditioned conducting way. Afterwards, some thought it was lovely and relaxing, and some experienced almost stress. This is always the outcome of this exercise - and perhaps it tells you something about how you see yourself in the interaction between you and the music.

I then chose to involve them in a warm-up exercise I do with my own choirs, where they get to walk freely around the room and improvise with their voices, experiment and aim to find the best version of themselves. This was also done with accompanying movements in the arms, and here they impressed me with a surprising amount of freedom. This exercise took about 5 minutes, and afterwards they had the opportunity to express how they experienced it: "wonderful", "free", "freeing".... Lovely feedback that naturally led me to talk about the role we have in front of our singers - to release the knowledge and creativity the singers already have, to bring out the silent knowledge - to make it explicit. That it is not about imprisoning the children in our own perception and knowledge, but through involvement and liberation build the choir together. An interesting comment came from their normal teacher on this course – "the kids are already free – we just need to allow them be free..."

The last hour of this session was used for musical direction of the group – each of the 6 teachers got 8 minutes in front of the group. It is not a lot of time, but enough time for me to identify what I thought were fundamentally important things to explore and contextualize. I think it is interesting to note that even though these were beginners in the trade, and very nervous about exposing what little they thought they knew, there was never any doubt about going up and doing what had to be done. This is clearly a product of the culture they have grown up in – that when someone expects something, you meet it without hesitation or questioning. This is quite different from what I experience in Norway and at my own institution – that when I open up to meet some expectations – to do what needs to be done – the students are often passive, hesitant and reluctant... But then again, they are also a product of the culture they grew up in...

My second mentees

This day was all about my meeting with my mentees at Carmel Pak U secondary school, a school for both boys and girls. First, an introductory meeting with the two mentors - here called Karen and Peter - who share the responsibility for this fine choir, about 60 young people of which 7 are boys, the rest girls. We talked for half an hour about expectations for the program, the mentees' own wishes for professional development areas. One main focus they both expressed was efficiency during choir rehearsals.

Then followed my observation of regular choir practice. These observations formed the basis for the debriefing we had afterwards. And the main focus they themselves expressed, became very clear during my observation. After my experiences both earlier this year and now during these two observations, choir rehearsal efficiency through wise methodological choices appears to be a subject area that should be stimulated and developed. Throughout the rehearsal, the pupils are conditioned to relate more to the notation than to listening – listening both horizontally and vertically, and not least to themselves. The fact that you then use the piano to a far too large extent does not help them with the development of aural skills. The pace of work can also be higher.

There is quite a small degree of involvement in the work, but mostly the pupils are passive recipients. What was a very positive observation was the good, warm and relaxed atmosphere that prevails in the rehearsal room. This is due to the fact that both teachers in themselves are very warm and good in front of the students.

At the end of the debriefing, they were both given both collective and individual tasks to work on until we would meet again digitally. These tasks were about musical, methodical and personal things. This choir rehearses one day a week, after school hours 16 -18. Interesting about these young people is that no one takes part in this choir due to a credit elective. They are there solely because they wish to be there. And that is noticeable - the motivation is high, the practice room is large and airy (and not too noisy!!) and they can also use several rooms for practice (since it is after regular school).

Meeting the program choirs:

Today was the day for us mentors to meet the choirs that belong to our mentees. The project will end in June with workshops and masterclasses as now, but also with a concert where all 5 choirs with their mentees will have a section each. We, the mentors, will also lead our choirs with two songs each. Introducing and rehearsing these songs therefore became the focus of the day's activity.

This was a demanding exercise. You have a room that is large enough, a temperature outside that is high enough (close to 30 degrees..) and air conditioning that therefore has to be turned on quite a lot. This creates a quite high noise level, which in turn leads to my communication with all 220 young people, having to take place with microphone, which in turn disrupts my natural communication.

And framework conditions factoring in to rehearsal efficency, is something we both mentors have tried to focus on – noisy sound, cramped spaces, untidiness... All of this contributes to reducing the opportunities for good listening in the ensembles – a common feature we clearly observe. Without understanding this, it becomes utterly difficult to try to bring about change in listening in particular; one has to try to change the framework factors. But, these are school choirs... So what to do? Force the students to have the choir after school? Not always possible – then many are already on their way to "cram-schools". Should you extend the rehearsal time in the middle of the day? Hardly.. that would create enormous scheduling complications. No, unfortunately this is not easy to solve.

I placed my young people by their parts and with the voices that cooperate the most next to each other, so that they could support each other. Ideally, I would have changed the entire placement, but with only about 90 minutes at my disposal to go through my two songs, this was not possible- The two songs I introduced are:

«Tundra» by Ola Gjeilo

«Pols fra Dunderlandsdalen», arr. by Ragnar Rasmussen

two good examples from Norwegian choir music - reoresenting folk music and art music. My goal was to bring this music up to a level so that they can continue to practice them appropriately until we meet again in June. I reached the level I wanted just in time.

I placed my young people by their parts and with the voices that cooperate the most next to each other, so that they could support each other. Ideally, I would have changed the entire placement, but with only about 90 minutes at my disposal to go through my two songs, this was not possible- The two songs I introduced are:

«Tundra» by Ola Gjeilo

«Pols fra Dunderlandsdalen», arr. by Ragnar Rasmussen

two good examples from Norwegian choir music - reoresenting folk music and art music. My goal was to bring this music up to a level so that they can continue to practice them appropriately until we meet again in June. I reached the level I wanted just in time.

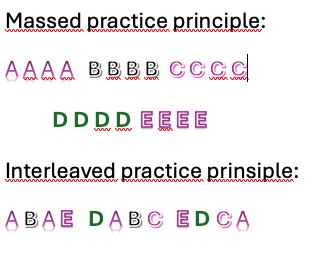

Since I earlier had introduced my mentees to "Interleaved practice" as a practice method, I used this method throughout this session; A maximum of 10-12 minutes on each part I practiced before I jumped on to another part of the song. This is a method that is increasingly practiced in schools, and of course it also works in choirs. The starting point for the method is recent brain research that says that the brain must be stimulated with something new after about 10-15 minutes. Two sources I lean on in this my own development of rehearsal methods are Daniel J. Levitin's "This is your brain on music" (2017) and Sharon Paul's "Art and Science in the choral rehearsal" (2020). To the right is an example of how to work with shuffled learning, and reflects how I myself carried out the exercise:

The image to the left visualizes the difference between massed learning practice and interleaved learning practice

I myself have no doubt that this method was what allowed me to so quickly reach a good level of knowledge, even with difficult physical/communicating framework factors, being new to the young singers and the relatively short time at my disposal.

Over the years, I have myself developed a similar strategy for studying music with my choirs, without being aware of the scientific theories supporting my own practice theory – that it actually had a name. Understanding what the students understand – or don’t understand – is fundamental in all good pedagogy. This is by far new – the Danish philosopher Søren Kirkegaard (1813 – 1855) shared these ideas in the art of helping with the world in “Kirkegaards Writings, Vol 22”:

If One Is Truly to Succeed in Leading a Person to a Specific Place, One Must First and Foremost Take Care to Find Him Where He is and Begin There.

This is the secret in the entire art of helping.

Anyone who cannot do this is himself under a delusion if he thinks he is able to help someone else. In order truly to help someone else, I must understand more than he–but certainly first and foremost understand what he understands.

If I do not do that, then my greater understanding does not help him at all. If I nevertheless want to assert my greater understanding, then it is because I am vain or proud, then basically instead of benefiting him I really want to be admired by him.

But all true helping begins with a humbling.

The helper must first humble himself under the person he wants to help and thereby understand that to help is not to dominate but to serve, that to help is a not to be the most dominating but the most patient, that to help is a willingness for the time being to put up with being in the wrong and not understanding what the other understands.

Meeting music teachers – a workshop:

An early morning awaits, to take me as quickly as possible to the next assignment – 3 hours workshop with music teachers for Primary school who also conducted a school choir. I met a relatively timid group of 14, most of them aged 25 – 35.Does the fact that there were only female teachers reflect a gender unbalance in the education system? Are there more female teachers in primary school? The first responses I got from my Hong Kong colleagues, indicates that Hong Kong reflects Norway in this respect. A further investigation of this will hopefully either substantiate or negate this.

My first focus was on warm-up/preparation. An attempt to converse about what we are actually preparing in this first phase of a choir rehearsal did not lead to much activity from the participants. Only when I put words in their mouths did they dare to engage in a dialogue. But, I knew that my play activity would lead them to "warm up", with the focus on the principle that the play activity should not only be an activity, but that being founded on conscious knowledge development, be it on a social or musical level. The contextualization I moderated after each activity created a great engagement in them.

The second focus area was repertoire, where I presented two songs to them, both of them Sami music by Frode Fjellheim – "Night Yoik" and "Eatnemen Vuelie" from the film "Frozen". I was initially pretty sure that "Eatnemen Vuelie" would be known to them – that they had been familiarized with this music from before, but that was surprisingly not the case. So it was nice to be able to present both of these songs to them – they fell into good soil, relevant to their own choirs.

A third focus area I had been asked to address was conducting/gestures. I did work with this topic, but quite quickly chose not to work with beating figures when I saw that they already had a good enough grasp of this. I therefore turned my focus more towards how they actually practice conducting/gestures, and exemplified this. In my experience, many conductors do not understand how to practice their instrument, or that they need to practice it at all. Therefore, I think it is important to address this and give concrete, practical examples of how to do this. Also here I used the free movements to recorded music, just like in the conducting workshop already mentioned.

The fourth focus area was about vocal development/awareness for the children. I have noticed that there is often a rather excessive focus on head voice in vocal training. It was therefore timely to talk to these 14 teachers about how they view the difference/similarities between vocal styles - head and chest voice. I introduced a good and rhythmic exercise, beneficial for the use of the chest voice in a good and inspiring way. Interestingly, however, as soon as they all started singing this exercise, the pre-conditioned head voice immediately defined the exercise. By implementing kinesthetic amplification using hands, I got them to find the natural chest voice, and in the exercise use this to understand the difference. This immediately had a very positive effect and they quickly realized how to alternate between the two. For me, this moment was very important – this was really something they could translate into their everyday life with their children.

After completing these focus areas, I asked what each participant felt was the most important thing to take with them. The answers that came were:

- To allow the children to develop independence in the choir

- To always connect an activity to knowledge building

- How to work on developing both the pop voice and the classical ideal

All in all - a successful and relevant workshop!

Meeting a choir with their teacher - "I AM":

Then it was time again for a clinic – a visit to St Catharine's School For Girls. This was a happy bunch, about 30 girls aged 12 – 16. The commission for me was about:

To strengthen students' projection of voice and breath, to improve the tone quality;

I started by asking the teacherto perform the warm-up as she usually does. This is to see if she uses her own exercises consciously to strengthen what she has asked me to focus on. Immediately I saw that her exercises could be much more strongly linked to both voice projection, breathing and sound development. By connecting her body to her own exercises, the experience of deep and quiet breathing was reinforced. The girls exhaled after I led the exercise as if they had just made a vigorous bodily effort – just as intended. Singing supported is so important to these young girls – but then they also need to know what it means to sing supported, how it feels and how it sounds. By alternating between supported and unsupported singing, they understood the difference and I was able to draw on this later during the rehearsal.

We continued to work in this way, where through kinesthetic reinforcement I could develop her own exercises, rather than giving her new ones. I think this is a fundamentally important pedagogical point – to use what they have and change this, give them a new suit, a new function. Then the students can also focus their attention on how to do the exercises, rather than on what to do.

The next focus point was expressed in the song we started working on, where the focus was on storytelling through awareness of the language and pronunciation. Throughout my stay here in Hong Kong and in my meetings with various choirs, the focus mostly seems to be on notes and not melody lines connected to text. The song became monotonous and apparently completely without awareness of strong/weak syllables. Here it took a lot of repetition and stops every time they did not respect the prosody in the text.

At the same time, this moment gave me the opportunity to focus on who in the choir is responsible for telling the story in the music. In the dialogue between me and the singers, it was clear that they naturally placed this responsibility on everyone in the choir - "We all are..". Not entirely unexpectedly, I could then turn this towards the fact that it is I in the choir who has that responsibility. In the competition they will participate in in March, each and every one of them must own their individual performance, have their own story to tell, so that whoever you look at in the choir, you see that singer's version – not the choir's or the teachers’s.

This developed into a question from me about who is responsible for the intonation in the choir? A few seconds of pause followed, then one of the girls pointed to herself and said "I am...?..." «wow, here's one who has understood the concept of responsibility in the choir".... Several then followed and pointed to themselves – "I am" .. This was absolutely epic moment!! Not least to see the expression they had in their eyes – they were radiant! "What about phrasing then" - collectively: "I am"... precision in time/rhythmics? "I am"... Dynamics? "I am" ... The moment when they realized that they're in control themselves. I do believe this will really help them. Their teacher stood next to her with a happy smile – beautiful!

To compete or not to compete….:

My colleague Susanna Saw, gave an inspiring talk about sharing impressions and thoughts about preparing young children for singing competitions. Singing competitions are a common phenomenon in Asia – where children as young as primary school students are encouraged to participate. Again, the competitive element shines through, and the actual discussion about whether children should compete at all seems completely absent. Susanna's review was very thorough and covered many basics in elements both from the preparation and from the competition itself. At the end of the lecture, I was invited to share my thoughts on this. For me, it was important to focus on whether it is justifiable to let such young children compete? In Susanna's lecture, she repeatedly highlighted the challenges of this – parents and the school's need to promote how good the school does to the local community, all in order to recruit children and parents to apply to that school. For many schools in Hong Kong, success may seem to be measured by the number of trophies the school can display from various competitions in sports and culture. I think we have to go quite far back in Norwegian school history to find the same thing. But I certainly believe that we have also had that attitude. Within the choral world, this is discussed at both national and international level.

«...And I used to think that competition could be healthy and fun if we kept it in perspective. But there is no such thing as ‘healthy’ competition. In a competitive culture, a child is told that it isn’t enough to be good. He must triumph over others. But the more he competes, the more he needs to compete to feel good about himself. But winning doesn’t build character; it just lets a child gloat temporarily. By definition, not everyone can win a contest. If one child wins, another cannot. Competition leads children to envy winners, to dismiss losers...» Alfie Kohn, author of No Contest: The Case Against Competition (https://www.ineos.com/inch-magazine/articles/issue-5/debate/)

“Competition is good for children. It is quite normal for people to judge themselves against others, thus in that respect competition is quite healthy. In a supportive environment it can teach a child to accept failure without losing self-esteem. However, it becomes unhealthy when the competitor is forced to compete or feels that they have to compete in order to gain love or status within the family.” Lyn Kendall, Gifted Child Consultant for British Mensa (ibid)

When I clearly declared that I strongly disagreed with the principle of allowing children to compete because parents or school want it, but that it must be because the child itself really wants it, many nodded in agreement. That it to the child – and for that matter also for adults! – must not be about picking one winner in singing – since singing is an objectively unmeasurable activity. That you should rather establish levels – such as Gold, Silver and Bronze levels – that the children can be motivated to navigate towards. This is also the principle on which this festival – the Hong Kong Inter-school Choral Festival – has been based. No one winner will be announced. And Queen actually sings "We are the champions...".

My third and last mentee:

Then followed a briefing together with mentee no. 4, teacher of the Precious Blood Girls Choir. This time it was Sarah – as I call her here – whom I have met before, when my choir Defrost Youth Choir visited this fine school.

I made some observations already then about this teacher, so when I heard that Sarah was one of my mentees, I was glad to reconnect with her. Sarah was very honest and sincere, and really put into words the things I was a little worried about from my first meeting her. In all her honesty, it was never a question of blaming anything else or other than herself, for the choir not developing as she wished. This honestty is the best starting point for a process where you put yourself under the microscope. And once again, it was a lot about the efficiency of the exercises, help with methodology, tools...

In the process that followed, where she was to carry out a completely ordinary exercise that I (and my local co-mentor) were to observe, she took to heart an organizational tip I gave in the briefing – to place the voice parts in circles. This is to create a clearer sense of belonging to their voice, help each other in the rehearsal (since they can hear each other well), but also that everyone in the circle is equal. In addition, it allows the teacher to get a little closer to each circle/voice. In the debriefing the next day, she expressed great joy about this method – using placement of the singers as a method for effective learning.

On the whole, I must be honest to say that there were many things here that need to be adjusted along the way – Sarah's own intonation, activity level that tends towards stress, untidiness in the rehearsal – everything seems somewhat unplanned... . Some of this is connected to her as a professional, other things are connected to her as a person – the person behind the professional. In a mentoring process, you cannot separate these – they belong together.

What caught my interest the most in her work with the girls was the relationship between reading the solfa syllables and singing the lyrics. Solfa is method is something the students are drilled on from primary school. They are good at reading the solfa-syllables relatively fast, and I only saw scores where the abbreviation for the syllable was inscribed. A good piece of preparatory work that the teacher must do.

Sarah started teaching the two parts (sopranos and altos), and after about 20 minutes of work, I could hear that they knew their part about 90%. Then she begins to rehearse the choir by singing the lyrics to the same part she has just rehearsed. Suddenly the girls no longer knew their part! So then Sarah has to start teaching the parts again, this time with the lyrics.

How can it be that a part once learned with solfa, is totally obliviate with the correct lyrics? I find this highly interesting, and it is something we will investigate further together in our mentor group. One can assume that through many years of conditioning, strong synapses have been established in the part of the brain that handles the solfa – which I imaging must be in the left hemisphere, solfa being a kind of language with syllables. The experience of music is mostly handled in the right hemisphere. Even though solfa is in a sense also a language, maybe the meaningful words connects more to the music itself, which could possibly explain why they seem unable to connect the solfa with the words and music?

I consulted my mentor colleague Susanna Saw from Malaysia, who is a Kodaly method exper, on this issue. She confirmed that this is a very common phenomenon in the Asian countries where solfa is used. The problem – according to Susanna – stems from not using Solfa functionally – as it is intended to be used. Solfa is a tool for understanding harmonic and melodic structures. She herself did not want to encourage teachers to use solfa – because they do not have the necessary training in understanding solfa on a deeper level. If you use solfa initially in learning, you must give the students a transition to the text by using neutral syllables such as no, no, or la, la... It made sense for me to consult an expert in this matter like Susanna – and it confirmed my own analysis of the phenomenon.

I gave my mentee the task next time to start with neutral syllables, then go to the lyrics, and as a third level possibly use solfa. But then you also have to ask yourself why you would use it at all? Then it has nothing to do with the musical expression, but only a cognitive understanding of what is going on. This is also congruent with a common and good method – first to experience, then to understand.

In order to bring out more empirical data through my mentees' work, by shedding light on the issue from a neuro-perspective since this phenomenon was not unique to this teacher and this group of students, all mentees have now been given the task of using solfa only to give the students an understanding of how the notes are connected as melody and harmony. The result of this joint exploration will come in Reflection – part 3.

In the debriefing that followed this rehearsal, I felt that I had to go into the things that might be sensitive. Sarah was genuinely happy that I put my finger on the things she herself felt she did not have good enough skill in. A nice and constructive conversation about how we should proceed to slowly but surely adjust her work, and a good foundation for continued constructive talks.

Summary:

To get so close to the work of these 4 music teachers is a privilege. The dialogue I have – and will continue to have until June 2025 – is characterized by curiosity and self-realization. These are never easy processes – putting yourself under the microscope where every little detail is observed, assessed and commented on. However, if you are to enter into change processes, you need a large portion of honesty and humility. One of my mentees has already realized that the professional change that is needed cannot happen without also a personal change. Her students will never primarily see her as a professional, but as the person she is behind the professional.

«Leadership on the whole will constantly be undergoing changes; changes that will manifest themselves in training of leaders in the corporate world, and should of course also reflect upon training for conductors – or teachers as I prefer to use. This will again necessary involve development of new – or at least – alternative didactic and leadership methods.

Music is all about humanity – where the teacher needs to learn leading the whole person behind the voice or instrument. If you can’t see the person behind and understand what she understands, you will be limited in your efforts to move her in the direction you want her to move. And your ensemble will struggle to reach its inherent potential.»

“Reflecting on - and rethinking - current practice in the field of conducting, leadership and up-to-date pedagogical psychology will inevitably equip the teacher with necessary tools in order to become the eclectic, compassionate and empathic conductor, growing from the inside out. (Caplin, Building the choir inside and out, 2025).

An equally important building stone in this building process, is how you nurture your own growth on a general human level. Skills in music alone does not give this growth. Digging into other fields like literature, languages, history, social studies, psychology and of course didactics, will aid you in your quest towards the eclectic and empathic and assisting leader – becoming able to understand the individual behind the voice. “ (Ibid)

The self-pronounced challenges my mentees want help with were consistently similar. This is also consistent with the picture I got from my first encounter with Hong Kong choral culture in March 2024. It is about building one's own self-confidence, developing more effective exercises through strengthened didactic insight. Another particularly interesting issue is the balance between the desire to develop the fundamental knowledge of vocal technique, intonation, rhythm, and the school's desire to produce choirs that win in choral competitions – the balance between process and goal. This will also affect me as a mentor, to what extent I can expect constructive, qualitative and long-term work with the mentees' students, while the teachers themselves are pressured to deliver quantitatively.

I empathically understand very well their challenges and struggles they will meet – we have to hurry slowly!

Sources:

https://blog.alexanderfyoung.com/interleaving/

https://www.ineos.com/inch-magazine/articles/issue-5/debate/

https://www.ineos.com/inch-magazine/articles/issue-5/debate/

Daniel J. Levitin: "This is your brain on music" (2011/17) Atlantic Books

Sharon Paul: "Art and Science in the choral rehearsal" (2020) Oxford University Press

Søren Kirkegaard: “Kirkegaards Writings, Vol 22”

Frode Fjellheim: Night Yoik, © 2001 Boosey & Hawkes

Frode Fjellheim: Eatnemen Vuelie , © 2002 Boosey & Hawkes

Ola Gjeilo: Tundra, © 2011 Walton Music Corp.

Ragnar Rasmussen: Pols fra Dunderlandsdalen, © 2003 Norsk Musikkforlag A/S, Oslo

Thomas Caplin: The Learning Conductor, © 1997/2005/2017 Musikk-Husets Forlag A/S, Oslo