1.4. The Earth: Sonic Citizenship in the Anthropocene

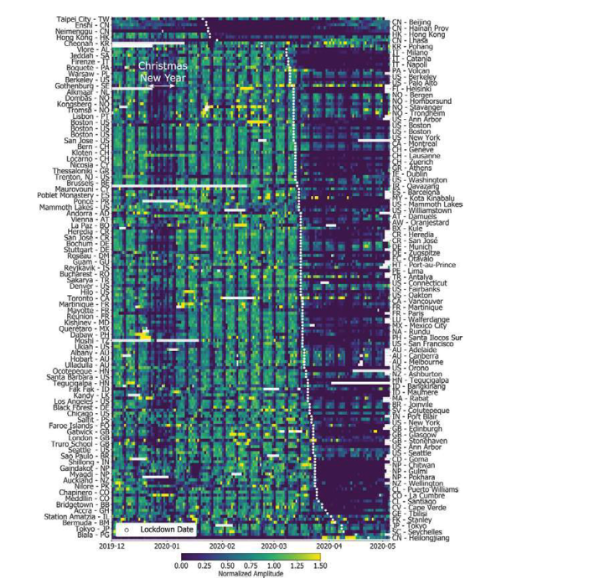

A predominant narrative on sound during the initial phase of the (partial) lockdown periods was that the world had become quieter because of the pandemic. Remarkable press images of abandoned streets from cities like New York, Paris, and Copenhagen were featured in public news media. In addition, scientists at seismic sites located close to cities published graphs of declining noise curves to illustrate this new, pandemic silence (figure 1).

Such reports may seem to be far from the local, messy perspective of our lived experience that is key to the concept of sonic citizenship. However, on a larger scale they evoke the same questions that we have debated in the analysis so far regarding how the collective is at play in our relation to sound. Questions about who has the right to make sound, who has the right to silence or who has the right to be heard were at the core of the reports detailing an increase in bird song due to the silencing of anthropogenic sound (Luther 2020). Researchers found that the alleviation of auditory pressures on animals that rely on survival and reproduction during the Corona lockdowns resulted in “higher performance songs at lower amplitudes, effectively maximizing communication distance and salience” (Derryberry et al. 2020). The world is currently witnessing a drastic, global biodiversity crisis, where not only habitats, but entire species are threatened, as described by the IPBES reports (Brondizio et al. 2019). Therefore, questions about how anthropogenic noise impacts bird song or communication among whales (Johnston and Painter 2024) raise broader ethical concerns about how we coexist with other species that have equal rights to livable habitats as well as more utilitarian questions concerning how we maintain livable spaces for the other species that we depend upon for our own survival. In this context sonic citizenship emphasizes the concerns regarding interspecies co-habitation that are currently emphatically addressed in both scholarship – for example, by authors such as the American biologist and thinker Donna Haraway, with her concept of “companion species” (Haraway 2003), or the Belgian philosopher of science Vinciane Despret, with her work on “the bodies we care for” (Despret 2004), as well as in the arts and field recording practices (Vandsø 2020). As an example, consider the American-Cuban artists Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla’s artwork The Great Silence (2014), which follows videos of the Arecibo Observatory and the Amazona Vittata parrots that are currently threatened with extinction. Through the subtitles, one parrot ponders why humans are so interested in listening to outer space rather than to the species they share the Earth with, even though both humans and birds are vocal learners.

The question of the right to be heard, as addressed by Sophie Rosenfeld in her research on the freedom of speech, as well the question of the right not to be severely impacted by the sounds made by others, takes on new relevance in an interspecies context where our failure to listen to other species and extensive anthropocentric sound production carries severe consequences. These issues lie at the heart of soundscape studies and acoustic ecology, as exemplified by the American field recordist Bernie Krause’s decades-long field recordings (Krause 2012). Sonic citizenship thus emphasizes concerns already present in the extensive field of acoustic ecology, such as questions concerning our ethical and social responsibilities to those we impact with anthropogenic noise as well as our obligation to listen (and thus pay attention to) our companion species.

On a larger scope the reports from seismic stations bear witness to the material entanglement between us (the social world of humans) and that which we often perceive as a mere background to our existence – our environment, or “nature” – which is characteristic of the suggested geological Anthropocene epoch (Crutzen and Stoermer 2000; Waters et al. 2016). What we see in these seismic statistics is that our everyday modes of transportation leave a mark in the very crust of the earth that is now saturated by human-induced seismic waves and infrasound (Ganchrow 2016). The trans-liminal nature of sound described by Andrisani, or Rice with his concept of sonic incontinence, therefore not only transcends the distinction between indoor and outdoor, private and public, it also challenges the boundary between humans and nature, a distinction we often take for granted, as seen when we differentiate between human history and natural history (Chakrabarty 2009). Sonic citizenship situates us as both listeners and producers of sound within a specific techno-material environment and place that we share with others. The seismic measurements demonstrate that, sonically speaking, we are not mere inhabitants of a globalized world, characterized by a matrix of financial transactions. Instead, we are earthlings; we are residents of specific places, be it our homes, cities, nations, or the Earth itself. In all cases, our relationship with sound is inherently a relationship with others. This collective dimension raises questions about belonging or exclusion from the social sphere and about power relations, rights, and obligations to the collective.

Figure 1: Global temporal changes in seismic noise. The daily global median is plotted, normalized to the percent variation of the pre-COVID lockdown baseline and sorted by lockdown date. Each line in the image corresponds to a seismic station. Data gaps are shown in white. Location and country code are given for each station. From Lecocq et al. 2020. Reprinted with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).