Disturbing Sounds

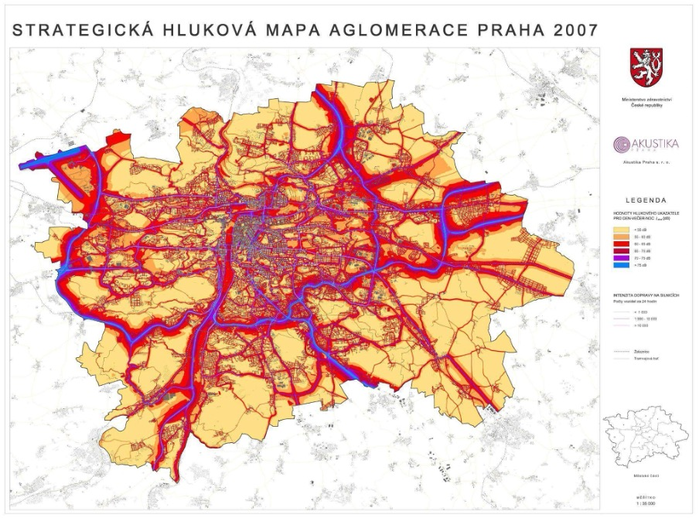

Throughout history, transportation has been identified as a heavy source of noise. According to Goines and Hagler (2007), chariots and horse riding were forbidden at night in ancient Rome because it would disturb sleep. Following industrialization, this complaint has only grown, and “within the European Common Market, 65% of the population is exposed to unhealthy levels of transportation noise” (Goines and Hagler 2007). According to the EEA Report No 22/2019,

Environmental noise from road, rail, aircraft and industry sources affects millions of people, causing significant public health impacts. [...] Long-term exposure to environmental noise is estimated to cause 12,000 premature deaths and contribute to 48,000 new cases of ischaemic heart disease per year in the European territory. It is estimated that 22 million people suffer chronic high annoyance and 6.5 million people suffer chronic high sleep disturbance. As a result of aircraft noise, 12,500 schoolchildren are estimated to suffer learning impairment in school. (EEA Report No 22/2019)

Although transportation is a clear example, there are many other sources of noise pollution; in fact they are ubiquitous in our society, some of them more necessary (e.g. to make our contemporary society function properly) than others. Notably, some of these sources are becoming more and more welcome in our households and social interactions.

The omnipresence of sound derived from household appliances is an increasing constant. In the domestic space, there are electronic devices everywhere, some more sonorous than others, some more constant than others: fridges, heaters, washing machines, dishwashers, vacuum cleaners, air conditioning, blow dryers, hi-fi sound systems, etc. In public spaces, there are smartphones and smartwatches with constant notifications, amplified conversations, and so on. “In residential populations, combined sources of noise pollution will lead to a combination of adverse effects such as impaired hearing; sleep disturbances; cardiovascular disturbances; interference at work, school, and home; and annoyance, among others” (Goines and Hagler 2007: 292). The implications of such sounds socially and psychologically are numerous and complex. Goines and Hagler expand on their analysis with a series of rhetorical questions, highlighting both sonic ambiguity and sonic subjectivity.

What about sounds that accompany an undesired activity, that have no societal importance, or that we consider unnecessary? […] What about the uncomfortable sound levels at concerts, in theaters, and public sporting events? What about the noise of slow-moving train horns in urbanized areas or the early morning sounds accompanying garbage collection? […] What about the risks to children from noisy toys and from personal sound systems? (Goines and Hagler 2007: 288)

Due to this auditory saturation, especially in overcrowded cities, it is understandable why many people want to isolate themselves with headphones and choose their own auditory input. Hence, “public space pushes into the private [... and] private space pushes into public” (Flusser 2005: 324). It is interesting to observe that this sonic isolation occurs in a way that also contributes to auditive saturation (loud headphones, constant input, etc.). Even harder to understand is the phenomenon in which individuals choose to have private phone conversations on speakerphone, adding noise to their communication while at the same time contributing to the saturation of the soundscape.

In other words, the complexity of this discussion resides in the relationship between sound and hearing, privately and publicly. Hearing is a constant activity, but it takes listening to notice it. The practice of field recording facilitates this, as it preserves a specific listening experience in time and unfolds a perspective of the space that may not be accessible otherwise. For that reason, field recording can be considered a research tool, which will be the topic of the next paragraphs.

Figure 1 – Strategic noise map of Prague in 2007