If these little threads are indeed 'remains' in the sense defined by the anthropologist Octave Debary, incorporating both the dimension of loss and conservation,1 they have the particularity of being the remains of other, more imposing remains: the tapestries. Discoloured, worn, holey and fragmented, old tapestries are part of our heritage. As the philosopher Vinciane Despret has written, an inheritance 'is not received passively, but is constructed. Inheritance is above all an act of creation'.2 While some old repairs are sometimes clumsy, performed with a coarse, disharmonious thread, they are nonetheless endearing, touching because each repair is a personal act of creation.

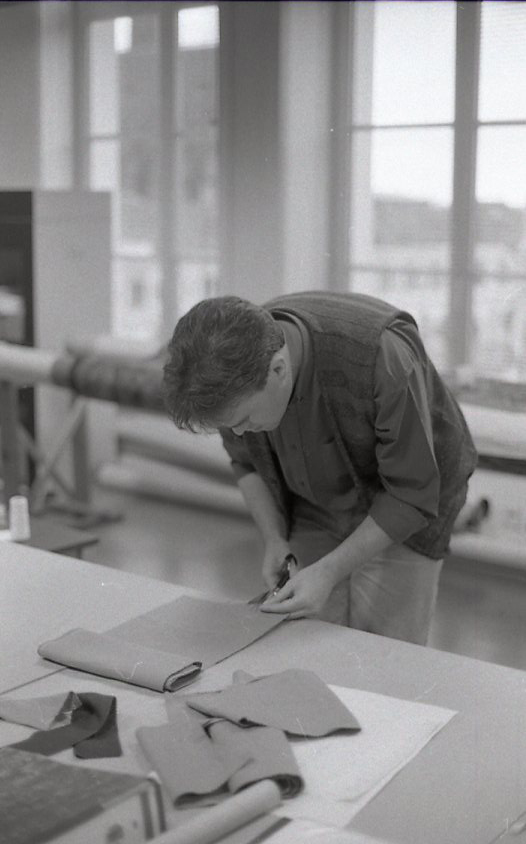

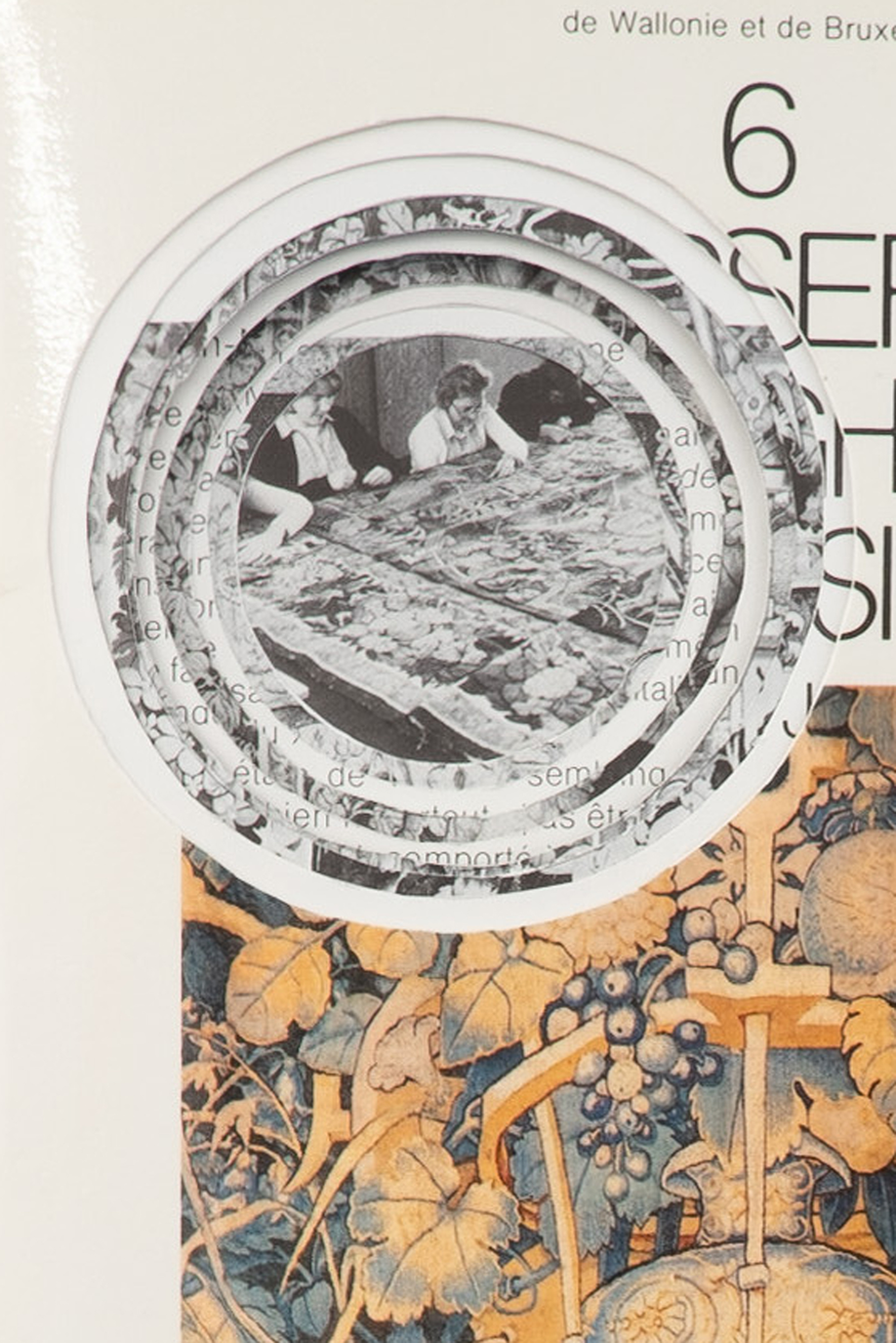

Inheriting these tapestries invites us to think about how to conserve and protect them and how to respond to the effects of time on the object. Most museums have a dedicated conservation and maintenance area. The TAMAT restoration workshop is unique in that it is always open to anyone who wishes to visit. The conservator-restorer is available to answer questions from visitors and professionals alike and to pass on expertise. The central position of the workshop - at the very heart of the museum, halfway along the exhibition route - is a clear indication of its importance and role.

The conservator-restorer's purpose is 'to fight the passing of time'.3 The yarn scraps we're looking at here bear witnesse to this same relationship with time. Even as the woven image inexorably deteriorates, thread by thread, humans cling to it, using a variety of methods to try to ensure an eternity to which they themselves have no right. Waste has a potential for truth, it 'doesn't lie'4 and in this sense it is the truth of the reverse. It is the other side of the object,5 including the patrimonial object, because of its ability to reveal who we are, to tell 'our stories without our suspecting it'.6 If everything is done to ensure that the tapestries live on, who's to say that, in the end, the fragments of the threads, the waste - admittedly very small but very resistant - won't survive longer, if kept, than the tapestry itself?

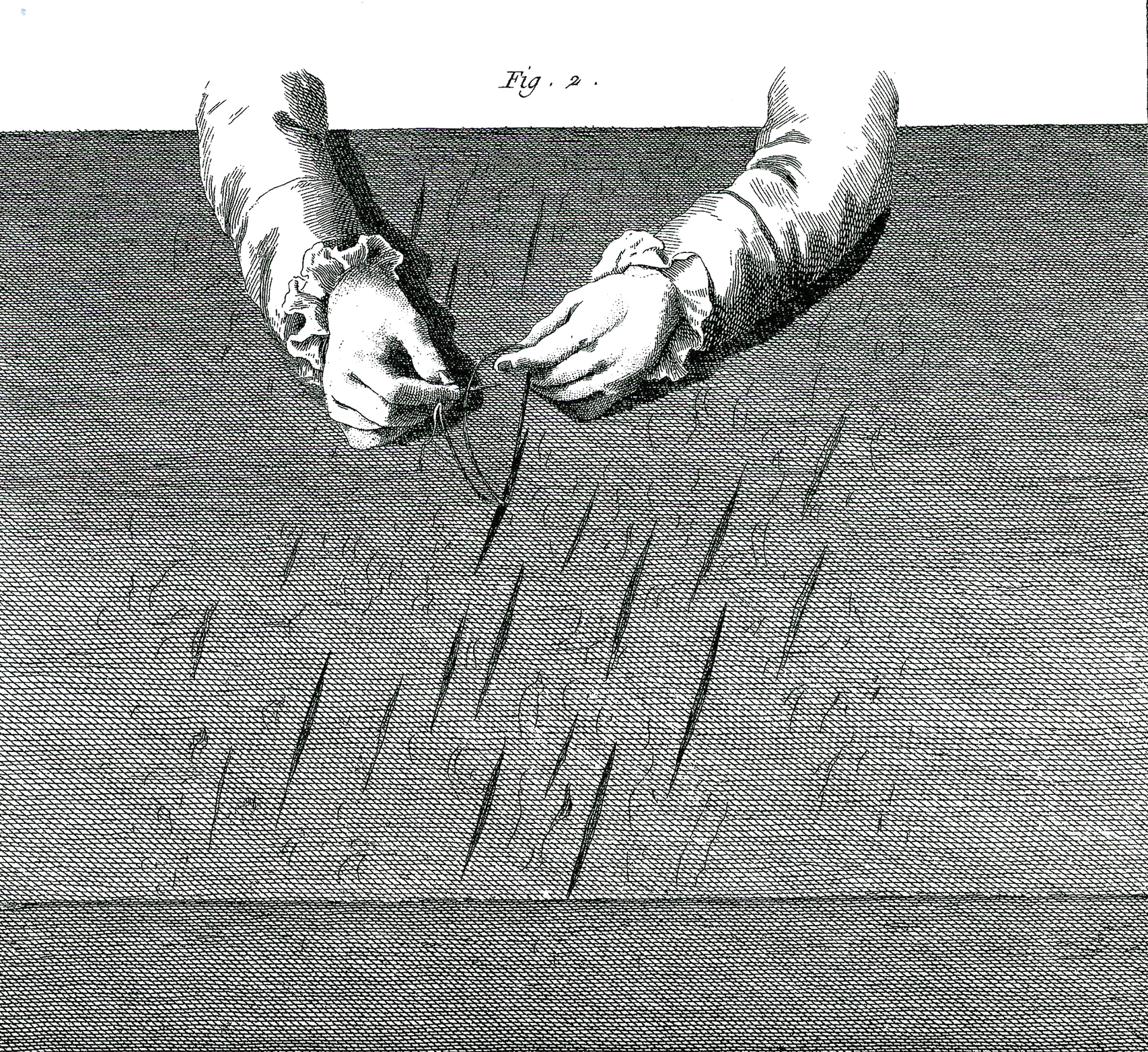

From the outset, tapestry required darning (rentrayage in French), a special finishing operation. This is a 'technical sewing or tapestry operation' consisting of 'giving an invisible limit to a tearing process'.7 Darning needs to be repeated whenever necessary, as the intermediaries gradually unravel with time and from the weight of the hanging tapestry. Seams give way, threads unravel, and the weave loosens. Isn't it incredible that the darner's trade is as old as the tapestries themselves?8 During the restoration of Les jeux d'enfants tapestry, the conservator-restorer took care to remove the unsightly stitches sewn between two colours, using a neutral thread to close the opening and allow the image to be read more fluidly.

Attempts at repair have been many and varied, both in the materials used (silk, wool, synthetics, cotton, etc.) and in the gestures (reweaving, cutting, reassembling, recomposing, recovering, sewing, etc.). But the gestures and materials of the past are still visible; they are embedded and interwoven in the material of the present. They constitute the substance of the present and, as philosopher Didi-Huberman points out, they enable us to understand it better by putting it into perspective. Significantly, on the back of an old tapestry that I was able to examine, I saw a lining made up of several pieces of recycled fabric. The observation bears witness to different conceptions of restoration in different eras. In traditional societies of the past, when resources were in short supply, the emphasis was on recycling, reparing with what was available. In our contemporary societies, where there is usually an overabundance, these fabrics would be removed and replaced with large pieces of plain, new linen. This was the case with Les jeux d'enfants, where high-quality linen pieces chosen to match the colour scheme were sewn to the back to stabilize the tapestry. The weakened warp threads were then fixed stitch by stitch to the coloured fabrics. As a result, different approaches to restoration have been adopted, depending on the materials available and the period in question.

Once restored, the tapestry will be conserved in museum-quality conditions so that any deterioration will be greatly slowed down, but there is no guarantee that no further maintenance or repairs will be required. Let us not forget that the tapestry has only been preserved this long thanks to a series of restorations; our scraps of threads from all periods attest to this. Doesn't the act of remembering, imbued with oblivion and loss, imply endless conservation and maintenance work?