In March 2023, I started conducting a series of site-specific improvisation performances in pristine or degraded ecosystems. The project, called [in situ], stems from my need to explore the space between social ecology, post-human environmentalism and improvisation. The ecosystem in which the improvisation takes place, with its human, more-than-human, living and non-living elements, is a fundamental aspect of the improvisation in [in situ], making each performance a unique and unrepeatable event (Erika Fischer-Lichte, 2008). It is a complex system linked to the place, the audience, myself and the time (Leonardo Barbierato, 2024). In September 2023,[in situ] was held in the Maremma National Park, as part of a week-long artistic residency called Dune-Utopie, focused on site/situation-specific art and the art-environment connection. During the first five days of planning and studying the area, I identified the performance space: a field approximately 50 meters wide and over 500 meters deep.

I had microphones for the environmental soundscape and my electric bass as sound inputs. The signal from the microphones and my instrument is routed to a mixer, which, through send-return, is connected to a chain of pedal effects, sampler, delay, loopers, pitch-shifter. Through the mixer, I can control the live sound flow coming from each individual microphone/instrument, partially or completely divert it towards these chains, modulate it with various effects, and send it to the speakers. The electroacoustic setup thus represents a key element for connecting the two systems at play, the performative and the environmental, allowing the sound flows/ideas from the environment and the improviser to blend and create something hybrid (on the description and operating mechanisms, L. Barbierato, 2024).

The elements of this meta-system are considered equally active and interact in a non-linear way, like any improvisational system (Marcel Cobussen, 2017): whether it is me, the audience, a cicada, or the wind moving the tree branches, each element has its own agency and is considered performative.

The term post-human here should be understood as an anthropic decentralization, an «abandonment of humanism but not of the human» (Cary Wolfe, 2010). Thus, it is not so much the exclusion of the human element in improvisation, but the shift of focus onto the relationship between post-human elements, or zoe (Rosi Braidotti, 2006) that is central during [in situ]. «There is no way of denying our partial perspective, our human sensorium and the specific capacities of our bodies. We have to accept being human, which is not to say that we should not value other forms of life. We need to acknowledge a life that is not ours – it is zoe driven and geocentered.» (Rosi Braidotti, 2017).

The [in situ] performance is thus an event of post-human collective improvisation. After technically organizing the setting and establishing a framework, the performances took place on September 15, 16, and 17, for a total of five performances at different times of the day. Each of these events was unique because, while remaining geographically in the same place, the time and elements changed. Even though I and some other elements participated in all the performances, our interactivity was different because our experiential and embodied knowledge led us to act differently based on previous experiences. Over the course of the five performances, my way of playing and listening to the ecosystem was influenced by previous experiences, and I felt increasingly reactive and focused, learning to manage stimuli – specifically by becoming aware of which stimuli to incorporate into my playing and which to exclude. Even the excluded stimuli contributed to the performance, even if they did not interact with me directly. Some human elements participated in multiple performances, and I noticed a different reactivity on their part too. It is difficult to generalize, but interactions tended to gradually become more intense and less soft over the course of the performances, both between humans and humans and between humans and non-humans.

In terms of intentions, the structure of the five events in Parco della Maremma was the same and the improvisation was preceded by a theatrical performance.

Afterwards, without providing further instructions, as the moving actor walked away, I opened the mixer channels dedicated to the microphones and let the ambient sound flow through the electroacoustic chain. From that moment, marking the beginning of [in situ], I had no idea what might happen and remained motionless, listening to the environment as a sound stimulus from which to start working on the improvisation.

During these five events, the interaction between the elements changed: initially the audience remained silent as if they were attending a traditional theatrical performance or concert. For this reason, initially, most of the stimuli came from non-human elements, such as wind, cicadas and birdsong.

Over the course of the five performances, there emerged, with progressively increasing intensity, a strong participatory dynamic that, especially from the third to the fifth performance, saw the audience becoming increasingly central in directing the course of improvisation and interacting with the performers. Particularly in the last two improvisations, a very intense dialogue developed between the audience and me, which marginalized the role of environmental sounds, and drastically decreased their impact on the improvisational system. I will specifically talk about the third performance, which took place on September 17th around 4:30 PM.

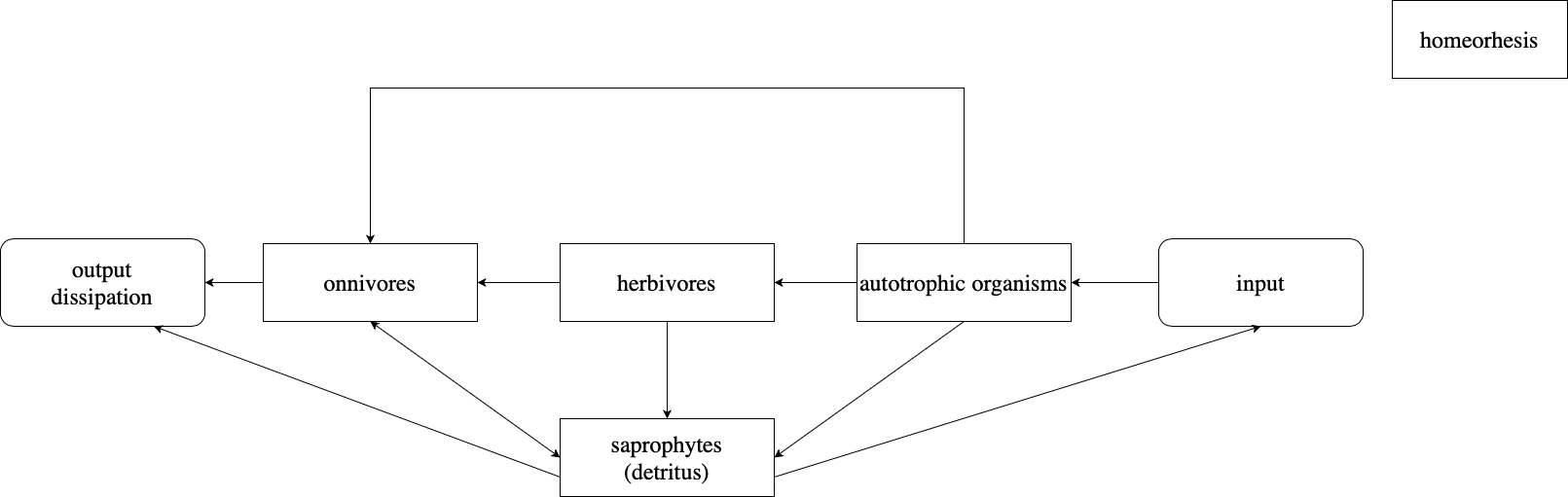

The relational and performative dynamics in [in situ] are in a dynamic balance similar to the ecosystemic ones. In an ecosystem, there is not a rigid stability but a continuous adjustment among different levels. To be sustainable, the energy and nutritional inputs and outputs of the ecosystem must be in balance, yet it is never a static equilibrium but a dynamic one, whose value can fluctuate over time. This equilibrium is subject to a series of controls, including feedback controls, where the downstream element controls the upstream one, as well as predator-prey mechanisms, parasitism-symbiosis, resilience-resistance. The type of equilibrium that results is called homeorhesis (Eugene Odum, Gary Barrett, 2006). It is an emergent characteristic, not observable through reductionistic investigation, but emerges only when considering the ecosystem at a higher level (for example, the level of a community).

As you can see in the video, the relationships between actants give rise to new behaviors. In my view, these behaviors emerged during [in situ] precisely because of how it is structured: open microphones on human and more-than-human elements allows for experiential knowledge of the agency of components traditionally considered inert and passive during improvisation performances. Not succumbing to the temptation to assume artistic control, but rather working to lose it without imposing predetermined behaviors on the audience, allowed the performance to disintegrate and reassemble as an event where there is no barrier between active and passive intelligences (Jacques Rancière, 2011) and where one approaches a sort of zoe-egalitarianism (Rosi Braidotti, 2017). In the first audio example at the end of the paragraph, some participants explore the sound of a pine cone and some water bottles that were discarded in the park. In the second audio excerpt, it is through the voice that a participant tries to relate with me and the instrumentation, finding a balance between the intensity of emission and the proximity to the microphone. The interplay between us highlights this alternative aesthetic of performance and, more interestingly in the context of this article, the behaviors that emerge within the performative system suggest a new ethic, a different conception of norms and values that govern (post-)human and non-human behavior in a momentary event. These emergent behaviors within the performative system suggest a new ethics, a different conception of norms and values governing (post-)human and non-human behavior in a temporary event.

The emergence of this ethics is probably associated with the disassembly of prevailing social and performative norms. Through their ruins, it is possible to reassemble an alternative scenario, a sort of Deleuzian assemblage (Gilles Deleuze, 1968), mutable and ephemeral: brieftopic. This brieftopia is closely tied to its temporality, and in this, I see an explicit materialization of Deleuze’s ontology from the perspective given by Paulo de Assis in the musical field (Paulo de Assis, 2022): in music, the concept of assemblage opposes the classical paradigm, where musical objects, such as scores and compositions, were thought of as well-defined and immutable entities, proposing instead an idea of music more akin to an event, where heterogeneous materials, signals, and functions aggregate, remodel, and disintegrate. According to Cornelius Cardew, while written composition is catapulted into the future, improvisation exists in the present: in its concrete form, it disappears forever the moment it occurs, nor did it have any prior existence before the moment it occurred, so there is no available historical reference (Cornelius Cardew, 1971). Even recordings and documentation, such as those I have included in this presentation, are essentially empty, as they separate the sound event from the space and time in which it occurred. But, despite this experiential and temporal constraint, the effect of the performance persists in the souls of the participants.

As we will see, this “remodeling and disintegrating” does not mean “being inconsequential” and has a potential that extends beyond the art world.

Resistance and resilience are examples of these emergent behaviors in ecosystems. Emergent characteristics, like transitions to chaos, are elements found in complex systems, thus also in improvisational ones (David Borgo, 2005). Situations of self-organization, transitions to chaos, and resilience are perceived during [in situ] both by me and by the audience, as intuited from what was said in the previous paragraph, and I believe it is a clear aspect for an experiential knowledge (David Kolb, 1974) of the performative agency of non-human elements (Donna Haraway, 2018). But, besides having performative relevance, I also believe that the potential of this experiential knowledge can be translated into environmental and social realms, recognizing agency in components traditionally considered socially and environmentally inert.

The concrete experience that the audience/actor becomes the starting point of an experiential knowledge that has the potential to propagate into society (Benjamin Simpkins et al., 2010). It is precisely in this possibility that the subversive and socially impactful potential of a certain type of artistic performance lies, and it is precisely this way in which this point event can reverberate and propagate over time, space, and society. In this regard, if sound is both ephemeral and linear/time-based, it can perhaps be argued that improvised music cannot be anything but a brieftopia. The brieftopic moment that manifests during the performance could be the moment when we realize our hyposubjectivity (Timothy Morton, David Boyer, 2022), where by “our” I do not mean a shapeless mass of living and non-living species, which would highlight the concept of “being all the same.” The hyposubject I am writing about are subtractive concepts, but not eliminativist, which represent a common ground between different species and elements. «They are content to play, take care of, adapt, get hurt, laugh. Hyposubjects are inherently feminist, anti-racist, colorful, queer, ecological, transhuman and interhuman. Hyposubjects are like squatters who occupy and inhabit cracks and cavities» (ibid.). Therefore, the brieftopia is a temporary context in which to develop hyposubjectivity and the changing, transitory, and sometimes violent interactions among the various components, whether human or non-human.

These behaviors sometimes lead to performative insights and moments of co-creation, as in these two examples.

A whistle is sampled and provides the foundation on which I and a human participant improvise through feedback and electronic modulations.

In this sense, the brieftopia, at least as understood in this article, is itself an hyposubject that with its brevity and depth contrasts with anthropocentric hyperobjects, which are instead phenomena so enormously extended in space and time as to go beyond human understanding (Timothy Morton, 2018). There are non-linear inter-relationships between these aspects, between the small and the large, between hyposubject and hyperobject, between brieftopia in performance and social and environmental change, between interspecies interactions and the balance of an ecosystem. Maybe non-linearity and complexity allow us to «open a space between what is and what might be, embracing the challenge of perhaps» (Davide Sparti, 2023)?