-

Wikipedia contributors. “Anna Maria van Schurman”. Wikipedia, 1 december 2023, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anna_Maria_van_Schurman.

-

“Anna Maria van Schurman - De eerste vrouw aan de universiteit”. Historiek, 21 september 2022, historiek.net/anna-maria-van-schurman-vrouw-universiteit/67986.

-

“De ludieke acties van de Dolle Mina’s”. IsGeschiedenis, 28 februari 2023, isgeschiedenis.nl/nieuws/de-ludieke-acties-van-de-dolle-minas.

-

“Dolle Mina actiegroep | feminisme | Atria.nl”. Atria, 9 november 2015, atria.nl/nieuws-publicaties/feminisme/feminisme-20e-eeuw/dolle-mina-actiegroep.

-

“Dolle Mina (Nederland)”. Wikipedia, 11 januari 2024, nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dolle_Mina_%28Nederland%29.

-

Stanford University. “How World War I strengthened women’s suffrage | Stanford News”. Stanford News, 4 mei 2022, news.stanford.edu/2020/08/12/world-war-strengthened-womens-suffrage.

-

“Aletta Jacobs”. Europeana, www.europeana.eu/en/exhibitions/pioneers/aletta-jacobs.

-

“Aletta Jacobs”. Canon van Nederland, www.canonvannederland.nl/nl/alettajacobs.

“Aletta Jacobs”. Wikipedia, 4 april 2024, nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aletta_Jacobs.

Anna Maria van Schurman (1607-1678) was a remarkable woman from the 17th century. A pioneer for women in higher education and has a lasting impact on the academic world.

She was born on November 5, 1607, in Cologne. From the age of eleven, she received education in Latin and later in Greek, just like her brothers. She was a humanist, linguist, theologian, poetess, and artist. She mastered many languages and was skilled in various art forms, including engraving techniques, paper cutting art, wax art, and pastel portraits.

In 1636, she was admitted as the first female student in the Netherlands at the University of Utrecht. She was allowed to attend some lectures, but had to sit behind a curtain so as not to distract the male student¹.She corresponded with important scholars of that time. Her academic attainment was praised, and her portraits hung in the Italian Academy of Sciences and the royal palace in Stockholm.

Aletta Jacobs began her medical studies, and in 1878, she successfully passed her medical examination. Consequently, she became the first female physician, and in 1879, she even earned her doctorate. Her dissertation was titled 'On the localization of physiological and pathological phenomena in the large brains'. Jacobs also advocated for women's suffrage. However, it wasn't until 1919 that women's suffrage was introduced. Three years later, the first voting rights for women were exercised in the Netherlands.

Aletta’s passion for medicine emerged early, inspired by her father’s profession. At a young age she defied norms by attending school, even though girls were not typically allowed. Her father insisted that all his children receive an education.

In 1870, Aletta Jacobs became the first Dutch woman officially admitted to a high school (HBS). A year later, she boldly requested permission from liberal minister Thorbecke to study at the university. Her letter, preserved in the National Archives, sought permission for university education. In 1871, she was admitted as a medical student at the University of Groningen, initially for a one-year trial period. Despite challenges, she persevered and in 1878 became the first known woman to successfully complete a university degree,making her the first female Dutch physician. Her doctoral research, titled “On the Localization of Physiological and Pathological Phenomena in the Large Brains,” earned her a doctorate in 1879.

She further sharpened her skills in London, specializing in women’s health and pediatrics.

Jacobs was a tireless advocate for women’s rights, education, and suffrage. Her activism extended beyond medicine.

As a doctor, Jacobs opened a practice to help women with contraceptive methods, including the use of the pessary. In 1882, she established the first birth control clinic in Amsterdam.

Jacobs also fought against workplace harassment and abuse, advocating for better conditions.

Throughout her career, Jacobs wrote several books, including the remarkable work titled “The Woman: Her Build and Her Internal Organs” (1899). Given her experience treating women, Jacobs had a deep knowledge of how the female body worked. This book likely contributed to female emancipation by providing women with knowledge about their own bodies, which was a radical concept at the time. It empowered women with the understanding of their own physiology, which was a crucial step towards gender equality. However, it wasn't until 1919 that women's suffrage was introduced. Three years later, the first voting rights for women were exercised in the Netherlands.

On June 14, 1956, a significant legal change occurred—the abolition of the “Wet Handelingsonbekwaamheid,” roughly translated as “incompetent to act.” Prior to this, married women faced severe restrictions. After marriage, they couldn’t work, open a bank account, or travel alone. In fact, some women were even fired upon marriage. Their primary role was expected to be childbearing and household management, while men provided financially. Legally, a married woman in the Netherlands was not competent to enter into contracts independently; her husband’s cooperation was necessary for any legal actions.

World war I played a significant part in the women’s suffrage movement in Europe and also the Netherlands. As women filled jobs vacated by men fighting the war overseas, public attitudes toward women’s role in society began to shift dramatically. Women’s contributions during the war were recognized, and this helped dismiss any remaining widespread beliefs that women were unable to cope with traditionally male jobs. Women’s significant role in the war effort was acknowledged by political leaders. For instance, by 1918, President Woodrow Wilson acknowledged to Congress that women’s role in the war effort was vital. The industrial demands of modern war also meant that women moved into the labor force and contributed to the war effort on the home front. This change in dynamics ultimately strengthened the suffrage movement. It however wasn’t easy. The fight for female voting rights was influenced by strategic considerations rather than principles of equality, freedom and justice stemming from enlightenment ideals. On the one hand you had conservative and religious parties which wanted to uphold traditional values by not letting women vote, but on the other hand also aware that it might be strategic to let them vote, because they are likely to preserve Christian values and family value. It was argued if womens’ suffrage shouldn’t be postponed to deal with other outdated or unfair aspects of the political system.

The late 1960s witnessed the emergence of two influential unions: De Man Vrouw Maatschappij (MVM) and Dolle Mina. Each played a distinct role in advancing gender equality:

-

De Man Vrouw Maatschappij (MVM): This group focused on lobbying the government for policy changes that would promote equality. They aimed to dismantle discriminatory structures and create opportunities for women.

-

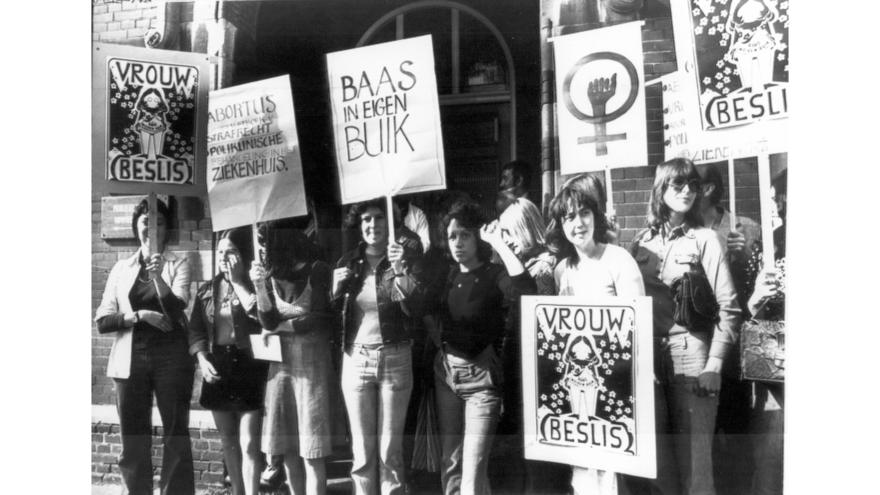

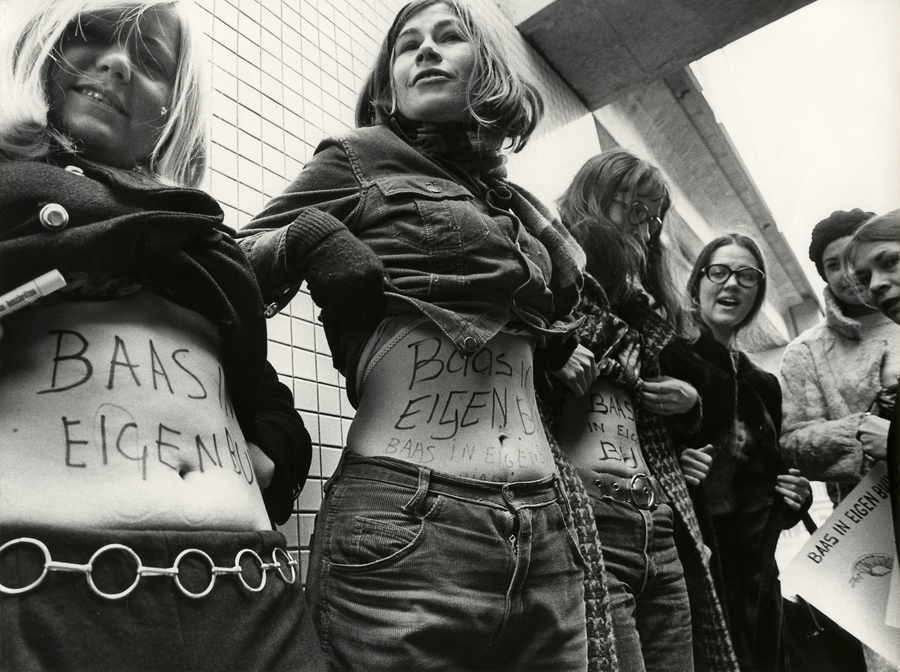

Dolle Mina: In contrast, Dolle Mina was a spirited group of activists who took to the streets, challenging societal norms. Their rallying cry included the powerful slogan “Baas in eigen buik” (Boss of my own belly), advocating for abortion rights and reproductive autonomy.

Some of their most important protests were:

Wilhelmina Drucker, a feminist during the First Wave of Feminism, lent her name to the Dolle Mina group. In honor of her legacy, the Mina activists gathered at her statue in Amsterdam.

Their symbolic act was the Burning corsets. These restrictive garments had long been associated with societal expectations imposed on women.

By setting corsets ablaze, the Dolle Mina activists challenged traditional gender norms and celebrated freedom from oppressive clothing.

The very next day after the corset burning, the Mina’s marched to the Amsterdam City Hall. To warn brides-to-be about the potential “slavinnenrol” (slave role) of married women. They distributed pamphlets with a provocative question: “Who will remove the hairpin from the sink?” This seemingly mundane task symbolized the unequal division of household labor.

Simultaneously, they staged a protest by blocking public men’s toilets (“de krullen”) to highlight the absence of public women’s restrooms.

The influence of the Dolle Mina movement spread beyond Amsterdam and Utrecht. In February 1970, new Dolle Mina groups formed in cities like Arnhem, Deventer, Maastricht, Leeuwarden, Tilburg, Den Bosch, Eindhoven, Breda, Vught, and Groningen.

But also across the border in Belgium people joined the chorus, with groups forming in Antwerp, Ghent, Leuven, and Brussels.

Some other things they did were, distributing condoms to students at the Huishoudschool (Household School) to protest the double sexual standard.

Disrupting a gynecologists’ meeting by launching the slogan “Baas in eigen buik” (Boss of one’s own belly). They demanded every woman’s right to terminate a pregnancy. (Even though abortion rights were not achieved until 1981).

They achieved all of this while maintaining a stylish and sexy appearance, leaving no room to be labeled as unattractive, dull spinsters. Dolle Mina activists often embraced a style that rejected traditional feminine attire. They favored clothing that allowed for freedom of movement and expression, often opting for practical and comfortable attire over restrictive or gendered garments. This could include items like jeans, t-shirts, and sneakers, which were more commonly associated with male fashion at the time.

In their playful yet powerful actions, the Dolle Mina activists left an indelible mark on Dutch society, pushing boundaries and demanding equality. Their legacy continues to inspire generations of feminists.