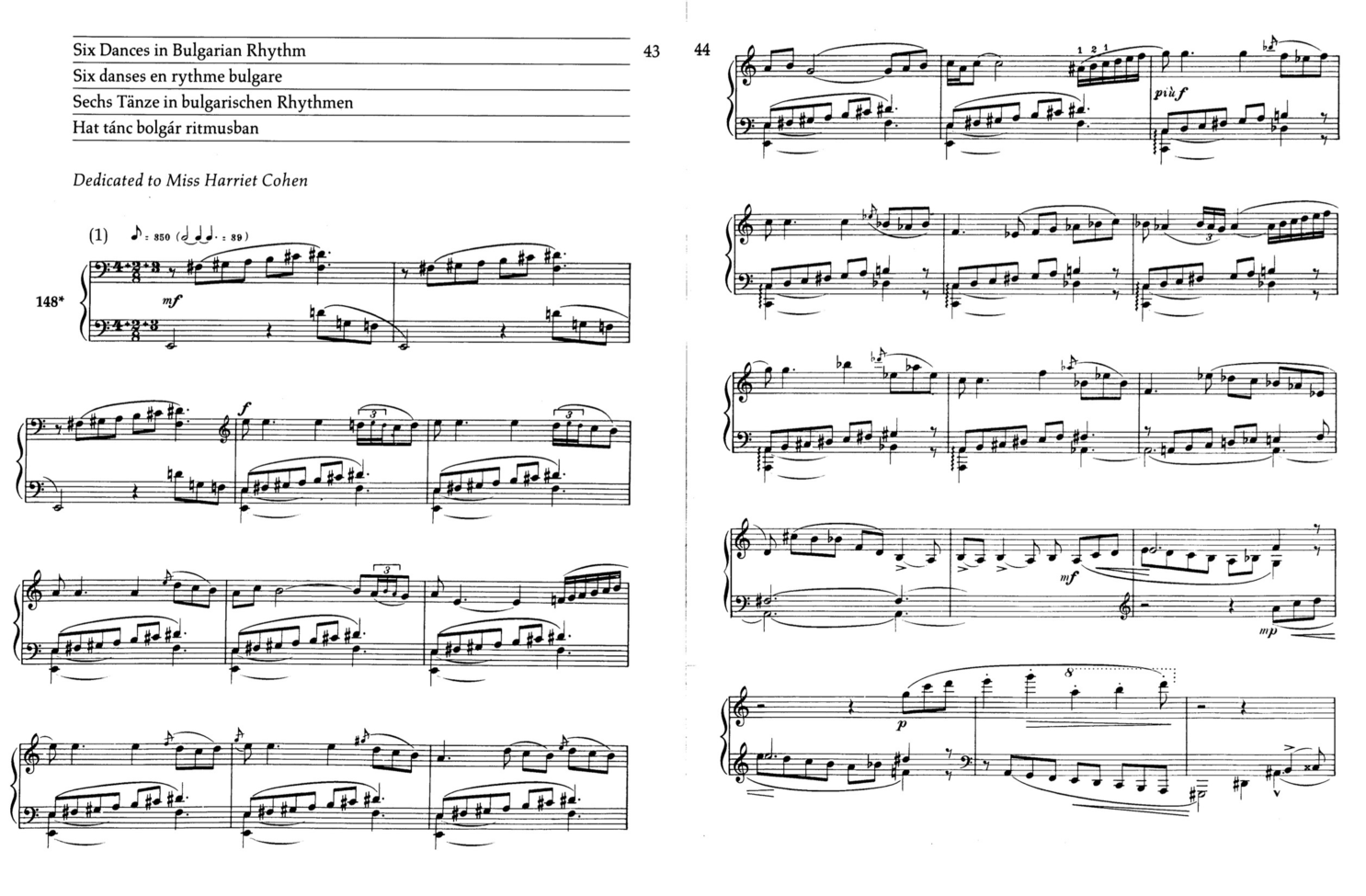

Movement II, bar 3-6 & 45-55

In bar 3-6, both the upper and the lower staff of the piano score are closely connected in rhythmic alternating staccato notes, forming together one single voice. I decided that despite being transcribed to two different instruments, the effect of one single voice should be maintained. To do so, I wrote the voices in the same register. As a result, the violin and guitar parts are in the same octave or one octave apart, whereas in the original they are one or two octaves apart. It is remarkable how the use of a smaller register is connecting the voices and bringing the two instruments closer to each, since the golden rule described above is to avoid having the guitar and violin in the same register, lest they overpower each other. In this passage, they are not overpowering each other because both voices consist of alternating staccato notes. There are two audio examples, one in a lower octave and one in a higher octave. The higher octave has a more defined and clear, direct sound. Because the violin part cannot be transcribed one octave lower, the guitar part should be transcribed one octave higher. In both cases, the guitar part is beneath the violin part, unless the original. As the violin part has the supporting bass voice on the downbeats, this switch of voices gives a strange effect. In bar 45-55 they do not overpower each other either because of the constantly descending and ascending violin melody which is floating through the guitar register, but not staying there.

Achieving a good balance between both instruments is a common stumbling block in violin-guitar duos. As the classical guitar is one of the quietest instruments, it is difficult to compete with other instruments in terms of volume. This has to be taken into account not only when playing together, but also when composing and transcribing. Throughout the transcription process, we have found that the balance between the two instruments is generally better when they play in different registers. Each instrument can then resonate and project to its fullest. When they are in the same register, the violin overpowers the guitar. If the violin has a melody that needs to be supported by the accompaniment, using the lowest register of the guitar is most effective. However, if certain notes or small melodies need to ring through, it is better not to play them in the lowest register of the guitar. For this reason, I have often transcribed passages in the middle register of the guitar, but doubled some notes in the lowest register so that there is still a palette of low notes.

Movement I, bar 4-21

In the piano version, the left hand supports the right hand, allowing the melody to sing freely over the accompaniment. This support is achieved by using the lower register of the piano, which gives a wide range of sound. When this accompaniment is played in the same register on the guitar, it has the opposite effect. It sounds muffled and doesn't have much resonance because it's too low. Transcribed an octave higher, it sounds louder and it is more supporting the violin. There is still an octave between the violin and guitar part, so they don't drown each other out.

Movement I, bar 1-4

In each bar of this section, there is a clear dissonance of D against D# in the same octave. Because the violin part is transposed one octave higher, there is one octave difference between the D and the D#, which makes the dissonance less strong. It is also less strong because the violin and the guitar have a completely different attack and the violin is a louder instrument. Therefore, doubling the D in the guitar part by adding it an octave higher and lower strengthens the dissonance.

III. Octaves

On both the guitar and the violin, octaves are a virtuosic technique. This is expressed in the sound, which is thicker, rounder and generally larger than octaves on the piano. In piano literature, octaves are often used to make a passage louder and more accentuated. Although octaves are also used to make a passage louder on the violin and the guitar, they add a different color too. That is why it is less common in the guitar and violin repertoire to write octaves. Therefore, it should be chosen very carefully and with a very clear intention.

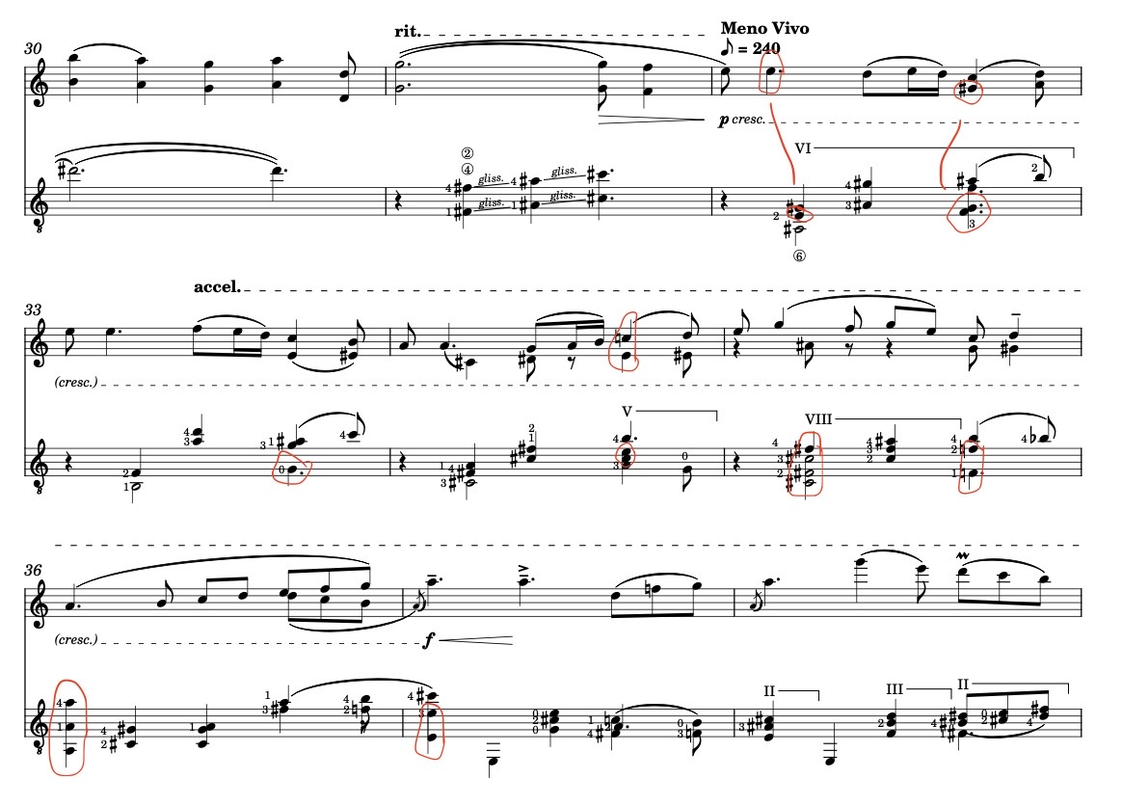

Movement I, bar 26-33

In the first movement, Bartók often writes them in the upper staff. In this movement, it is not always obvious to transfer them literally to the violin part. The octaves are very virtuosic on the violin. In bars 28-31, the markings mezzo forte and expression are written, and the lower staff is basically empty. At the end of the passage, there is a ritenuto leading to a meno vivo. We can therefore assume that this is a small 'solo' before the new section of the piece begins. This is why the octaves on the violin work well in these bars, as they actually emphasise the soloistic, expressive character and they have time to sound.

Movement V, bar 29

In bar 29, I decided to add octaves in the guitar part in the melody to give it more power and sound. This is explained chapter IX about dynamics.

Movement II, bar 1-15, 26, 27-30, 30-34, 55-64

Since many of the little melodies and rhythmic figures are written in bass clef, it is necessary to transpose them up one or even two octaves in order to play them on the violin.

In bar 44, however, the octaves are more difficult to play. Firstly, they are very high, and secondly, they are not a solo, as the guitar also has a part. In this high register it is difficult to produce a resonant, full sound, so it is easy to miss the point. They also lead into a new section, but there is a poco allargando, no ritenuto. The new section is not meno vivo, but calmo. It is not such a big difference, but there is less time to let the octaves resonate, and because they are so high and difficult to play, we decided to leave them out.

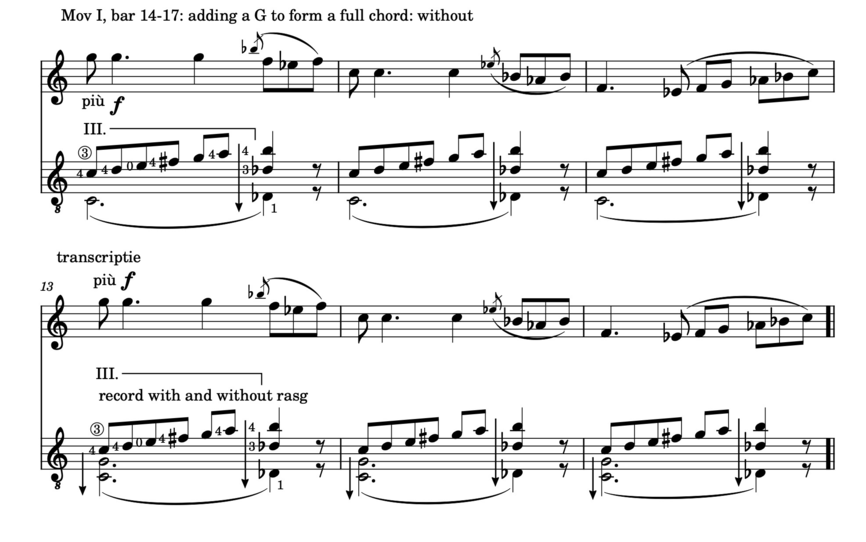

Movement I, bar 13-18

In bar 13, più forte is written. As for the forte before, the composer wants this part to be very loud. To support the strong violin part, it is necessary to have chords in the guitar part. This is the only way to make the guitar part more resonant. In bar 13, the chord is formed by adding a G to the two C’s on each first beat of the bar. The G is already in the violin part, so there is no new musical material. In the original score there is an arpeggio sign. To give the guitar part even more support and strength, I decided to add a rasguado instead of an arpeggio. That makes the sound more percussive and powerful. More about rasguado in chapter VII about articulation.

Movement I, bar 32-44

As mentioned before, the register in this entire section is too large to literally transcribe for guitar. There are a lot of big jumps. I decided to place the upper voice in the middle range of the guitar, high enough to resonate clearly, but not in the violin's register. I often didn't transpose the basses up to keep a wide range of sounds.