II.Inspirations

Before I got the opportunity to create a multidisciplinary work of my own, I was an audience member to a number of those already. That served as a pot of inspiration for the direction I wanted to take. Below I have listed a number of examples and described what they have inspired in “Inseparable”. In the beginning of each section I have provided the title of the performance and as a subtitle a summary of what the performance has meant for me. (For more information, please visit the dedicated page to this Chapter)

1. Snow in June by Leine Roebana, Tatiana Koleva, The (Youth) Percussion Pool and Jakob Koranyi

A seed to grow; a first contact with the collaborative cross-arts form.

"Snow in June" is a contemporary interdisciplinary dance and music performance. It was the first one of that kind that I saw. It was performed back in 2015 - two years before I moved to the Netherlands for my studies.

The music was composed especially for the occasion by Tan Dun and a number of pieces were added by Iannis Xenakis. The musical performance was by a percussion quartet - The Youth Percussion Pool, together with the artistic leader Tatiana Koleva and a cellist - Jacob Koranyi, accompanying a group of eight contemporary dancers.

The musical language and sound worlds were completely new for me. They ranged from very active and pulse-driven to abstract soundscapes, atonal melodies and silence.

As of 26.02.2024 the concept of the show was described in Dutch (translated to English for the research) on Leine Roebana’s website as follows:

"The world according to Tan Dun through the eyes of LeineRoebana. A world in which the animated landscape forms the backdrop for 'a journey of the soul', where humans and nature, fire and water, become unbalanced.

Snow in June is overwhelming at one moment, subtle and concentrated the next. The performance lets you experience how rich silence can be, how music never lets silence disappear, and how in a stationary dancer, the movement continues."14

That moment was also my introduction to this particular contemporary dance movement language. Back then, I couldn't take everything in. Both the musical, as well as movement languages were completely new for me. I still remember the impact the performance had on me and how impressed and drawn in I was. The activity of the densely textured moments, the deafening silences and the contrast between music and dance at times - those were the strong imprints in my mind.

I take this moment in time as the seed that was planted to grow later on.

2.Freedom by Club Guy&Roni and HIIIT

Inseparability

Freedom is once again a cross-disciplinary performance and this time the crossing part was even stronger than what I had seen before.

This is (part of) the introduction the website of NITE as of 26.02.2024:

"The always striking dancers of Club Guy & Roni and percussionists of Slagwerk den Haag reclaim the freedom unjustly taken from Mohamedou with an energetic 'in-your-face performance, where boundaries between dance, music, set and instruments blur. Together, they manage to create a polyphonic narrative where Guy Weizman's maximalistic approach returns in an associative , gripping performance that unddoubtedly will provoke dialogue.

The starting point for the dance performance Freedom is the story of Mohamedou Ould Slahi, who was unjustly detained for 14 years in Guantanamo Bay, where he was interrogated and tortured. (...) Ould Slahi, as a writer, advocates for a world where freedom is an inherent right and forgiveness is a core value. Mohamedou writes the original text for the performance as a 'writer in residence'at NITE for the 21-22 season."15

The main impact FREEDOM had on me was seeing the four percussionists (making the music live acoustically, with the use of electronics and pre-recorded tapes), being an interlocking part of the choreography throughout the entire performance. There was no separation between dancers and musicians in their presence on the stage, just as promised. Everybody was a performing piece of the storytelling by the entirety of the cast. Everyone was part of the choreography and an embodiment of the music. This inseparability of the artists struck a chord in me.

That was a definite element I want to embed in the performances I make.

3.Zamenhof Project: Breaking the Codes by Jerzy Bielski

Audience participation

The Zamenhof Project impressed me on many levels. The size of the production; the multiple abilities of the performers - acting, dancing, singing; solos, ensemble scenes, the use of speech and a band, playing music composed for the occasion; establishing contact with and managing an entire audience to obey commands; and much more.

The focus in the room was high. There were numerous elements used besides the performative ones - a wide number of languages, codes and signals; light design and installations to be climbed on; unusual costumes with various fabrics and elements.

Here is the introduction to the piece from Bielski’s website:

“It's a project inspired by the ideas and the life of a linguistic genius Ludwik Zamenhof. In this large-scale interdisciplinary piece Bielski constructs a world which surprises, challenges and confuses. His work, praised by the public and the press, is unconventional, limitless and deliberately outside any boxes. The international cast, consisting of actors, musicians and dancers who between them speak seven languages, involves the audience in an exploration of communication (or miscommunication) and language. An event in which music and visual elements such as theatre, contemporary dance, installation, video, set design, costumes and light are completely integrated. The traditional separation of stage and audience also becomes blurred.”16

The audience participation was something that left the brightest mark in that show for me. We were asked to change our seats for a new perspective in the middle of the show. We got split into groups, according to numerous types of physical features (at a certain point you lost the trace of where you belong to). As the audience was split into three parts and situated in the shape of a triangle, we were asked to face the wall, wave flags, obey commands, speak out slogans, do physical activities and were even shouted at if not following the commands. A separation in the group was created so fast that one could easily associate the happening with world scale events. I tried imagining the reactions of the different personalities in the room. This was a safe, yet highly provoking social experiment both for the performers, as well as for the audience. About a dozen human principles and tendencies were demonstrated and questioned during the performance.

The point of the show – unity and separation through or beyond (mis)communication became not only understood but also embodied by the audience's experience. Not only audience engagement but audience participation was key to challenging people to experience what the artists were sharing. This element I discovered, made a performance into an impactful and memorable experience. This feeling is something I want my audience to leave the theatre with as well.

Audience participation was an element in “Inseparable”, which was certainly not as physically engaging as in the above mentioned play but was meant to trigger the audience and provoke thoughts or even interaction with the performers.(Please refer to Chapter IV. “Premiere and Touring” for audience reactions after “Inseparable”)

4. The Circle of Truth

Co-creative multidisciplinary participatory nightlife experience

Cited from the website of The Circle of Truth as of 26.02.2024: “Inspired by the Faustus story of Thomas Mann, The Circle of Truth employs a revolutionary combination of theatre, art, nightlife, and digital culture to delve into our complex relationship with the truth. In this 2.5-hour interdisciplinary mindfuck, the devil himself assists you in stepping out of your comfortable social bubble to perceive the truth from a fresh perspective. The show spans across our 3000m2 warehouse at the NDSM, taking visitors on a captivating journey through interactive installations and performances by diverse local cultural pioneers.”17

The Circle of Truth is actually a performance I took a very small part in. The main composition was made by Nicholas Thayer - a composer, artist, musician and maker, mostly busy with electronic music creation, who happened to be a teacher in the conservatory I was studying in. He approached me for a one hour recording session for a project he was working on. I ended up recording most of the acoustic percussion samples he later on used in his final track.

Back in the studio I had absolutely no idea what my playing was going to be used for. I won't attempt explaining the experience, as that would take a few pages on its own but will only mention the major events that made this a somewhat shocking, eye opening, inspiring, confusing and profound experience:

- Audience participation - once again but this time on a much larger scale. The performance took place in an entire industrial building (NDSM). The audience was taken through its rooms on a two and half hour performance-filled tour. We were experiencing multiple stories that were being created for, with and by us. Each group would unknowingly see a slightly different story to the other, which made the discussions in the end (they facilitated plenty of communication between the audience groups that were formed) wildly fascinating and profoundly confusing.

- The possibility and organisation of such a large scale performance was something that staggered me. The combination was of electronic dance music, contemporary dance, theatre, a journey through an unfamiliar building, being blindfolded, led through a room, and adding nightlife queer elements to the mix, culminating in an electronic night club dance party. This mixture was perfectly synchronised and orchestrated to function simultaneously in a huge building with a few hundred people involved.

- The story was a melting pot of philosophy, satire, poetry, life experiences and many more, told through a contemporary underground reality's eyeglass.

- The real goal – creating connection and mutual understanding. Experiencing somebody else's story and being challenged to see beyond one's appearance or behaviour.

This project impressed me and I believe has a connection to “Inseparable” in that so many disciplines were interconnected. The storytelling and the hidden underline of presenting the three audiences with three slightly different scenarios was successful and indeed confusing. I loved that feeling of having been fooled. I believe we managed implementing this element of the audience being fooled in the very opening of Inseparable.(Please find audience feedback on this topic in Chapter IV.)

Research question

What is the creative process behind a multidisciplinary performance including cross-disciplinary practices with additional focus on audience engagement and social impact?

Research abstract

The following research observes the artistic creative process of a cross-disciplinary theatrical dance and percussion performance, called “Inseparable”. It discusses and analyses the process and methods behind the creation of the piece; the pros and cons of dance-percussion collaboration, and of working as a team of performer-creators; the involvement of a director; the creation of the final performance with a technical crew (light & sound); and the emergence of a mutual artistic language.

The cast includes Zaneta Kesik and Matija Franjes - two dancers (doubling as choreographers), and Joao Brito and Kalina Vladovska - two percussionists (doubling as composers), creating the narrative, dramaturgy, choreography and (some of the) music on their own. The director, Renee Spierings, was invited to be an external coach. Teus van der Stelt and Maurits Thiel - light and sound artists - took care of the final presentation. The four performances took place during and thanks to Muziekzomer Gelderland 2023 and were produced by Jarick Bruinsma.

Furthermore, in the research I discuss the social impact of the project's themes – technology addiction and human communication - and I examine a number of reactions and feedback from audience members.

The chosen form of presentation is a research exposition.

Bibliography

- Bielsky Jerzy, Zamenhof Project: Breaking the Codes, Work, last accessed on 26.02.2023 http://www.jerzybielski.com/work/

- Ford, Byranda. 2013. ‘Approaches to performance: A comparison of music and acting students’ concepts of preparation, audience and performance’ Music Performance Research, 6: 152-169, as quoted in Kossen-Veenhuis, Tomke. 2017. ‘The great thing about collaboration is that it never is perfect’ An Ethnography of Music and Dance Collaborations in Progress, 2.4 The Role of Notation page 39, PhD Thesis, The University of Edinburgh https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/25685?show=full (last accessed on 28.02.2024)

- Join The Circle of Truth, last accessed on 26.02.2024 https://www.jointhecircleoftruth.com/

- LeineRoebana, Snow in June, last accessed 26.02.2023 https://www.leineroebana.com/voorstellingen/snow-in-june/

- NITE, Freedom, last accessed 26.02.2023 https://nite.nl/en/voorstelling/freedom/

V.The Future

My aim from this moment on is to improve the show, develop the elements that we had to compromise on or left behind because of time limitations and expand on the material we have. Some of these elements include:

-

Representing the impact our devices have on us with even more impact (more consciously making bald choices, while also taking care of how extreme we can go with that) both at the opening of the performance within the audience, as well as during the speech scene;

-

Developing further the musical and choreographic material that we created;

-

Developing the story line and choosing places to make it more concrete or deliberately open to interpretation;

-

Expanding the length of the performance;

The aim right now is to take the performance on tour through the country and beyond in the summer of 2025/season 25-26.

By having completed the current research and conducted the interviews with the cast and crew members, I had an opportunity and motivation to contact them with clear questions and find out what they have experienced, would like to have done differently in a potential following production and would like to change/develop in the current one.

A follow up of this research is a new research that I am starting, together with one of the dancers – Zaneta – which would explore even deeper what the possibilities of crossing into each other’s disciplines are. Through discovering what could come out of that collaboration, we are aimed at presenting the outcome at my final master presentation in June in the form of a performance. Later on, this project would be taken further and offered to various festivals, venues and competitions.

VI. Conclusion

The current research focused on the analysis of the creative process behind the multidisciplinary dance, percussion and light performance “Inseparable”, including cross-disciplinary practices, with an additional focus on audience engagement and social impact.

Through a thorough analysis of the process, aided by audio, video and photographic documentation analysis, as well as a number of interviews, conducted with the cast, crew and audience members, I have presented the development of the project in time, the conclusions I got to after conducting this research and advice I received during the entire process. Additionally, the interviews with cast, crew and audience have provided deeper insight into the impact of the creation process on the team, as well as the performance as such on the audience. The information gathered, thanks to the conducting of this research, proves relevant for any further creative process I am to engage in from this moment on. Furthermore, the findings may prove relevant not only for dance and music/percussion collaborations but to any performance art’s collaborative creative process.

The impact of the elements of audience engagement and social impact in “Inseparable” has been proven successful through the feedback gathered during the interviews conducted with audience members.

The information gathered during the conducting of this research will directly be used to improve the performance “Inseparable”, as well as the future rehearsal and performance processes from this moment on.

I. The Idea and Preparation

1.Technology addiction

"This topic is very close to my heart. I was very happy to see that you brought this topic up so openly. I started realising that a lot of people are struggling. It’s a huge distraction. It’s drastically changing my brain, my attention span is getting smaller and affecting my memory., affecting the music I listen to. (...) It was a realisation for me that the topic might be something to open up about.”1

The idea for the creation of “Inseparable” came to me as a byproduct of something I had been doing, noticing and made aware of for a few years already. That was the rapidly growing issue of people’s (unconscious) increase in mobile device usage, most noticeably in my own peer group of ages 18-25 but certainly not limited to that frame.

This notion brought my awareness to observe how often conversations with the people around me were interrupted and hindered, thanks to their mobile devices. I noticed how people (including myself before) oftentimes react to a notification or a call in an unconscious compulsive manner, as if they were obliged to respond to the device and nothing else was of higher importance that second. The moment I got shocked and decided I wanted to do something about it is when I observed frustration and aggressiveness as response to one attempting to bring awareness to the issue, make a remark or demand the attention back to the initial conversation. One can notice how powerful habits can be and how our sympathetic nervous system can fire right away, as soon as it feels threatened by the lack of this newly created “safe space” in our hands.

A parallel motif for action was my own experience with social media and technology addiction, of which I am no less guilty or a victim myself and the moment it began interfering with my life.

I took on a journey fighting with myself (a battle I am still leading) against the addiction to my phone, finding new ways to limit my use and observing with fascination and - at times when it goes too far - profound frustration how creative I can be with sneaking excuses on myself just to reach to my back pocket again and again. It is an ongoing battle and a challenging one, since our society’s functionality has been centred around mobile devices. Nowadays we use them for the purpose of communication, planning, information exchange, everyday tools that have gone out of use thanks to the rapid development and practicality of phones (such as calculators and many more), education, work, promotion, pleasure, shopping, the capturing and sharing of memories and the list goes on…

I began talking to my closest ones about this addiction and aimed at making them aware too. Until today, I continue to meet strong resistance most of the time when the issue is addressed but opening up about my own experience always helps open up the space for others to share as well.

Those experiences gave me a powerful web of ideas that I wanted to convey in and gave the dramaturgical line of the performance, discussed in the current work.

2.Cross-disciplinarity

The nature of the collaboration was another aspect that was clear to me from the start. I wanted to experiment with the combination of dance and music performance (in particular percussion playing) in a cross-disciplinary manner. The term cross-disciplinary refers to the integration and collaboration of two or more disciplines. It involves combining knowledge, methods, and perspectives from multiple disciplines, often blurring the boundaries between those. The reason why I chose dance as the second discipline is because of my own developmental path as a performer. Throughout my entire childhood and adolescent years I have had dance as a complementary art discipline to music making. Music became my professional career path but the passion, focus and need for the inclusion of movement in my music making never left me. Movement and body awareness are a great focus in my everyday workflow when studying and preparing a piece or performance. Naturally, I wanted to take this one step further and find like-minded people to make the crossing of arts come true. (Please refer to Chapter IV. Premiere and Touring for audience feedback on this and other elements during interviews after seeing the performance)

3.The Choice of Music

As a classically trained musician, I sought for a central inspiration for the musical content of the performance in already existing compositions.

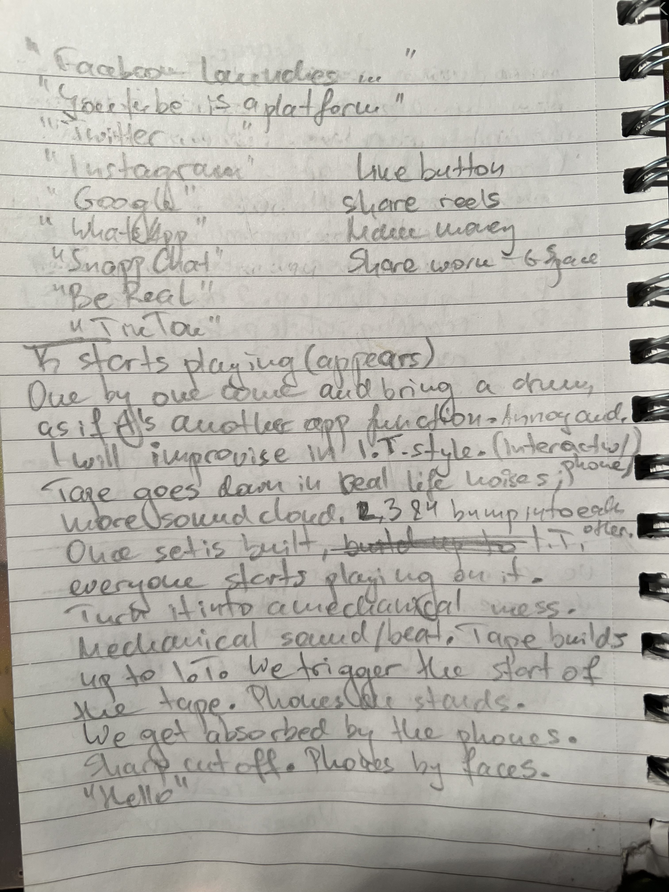

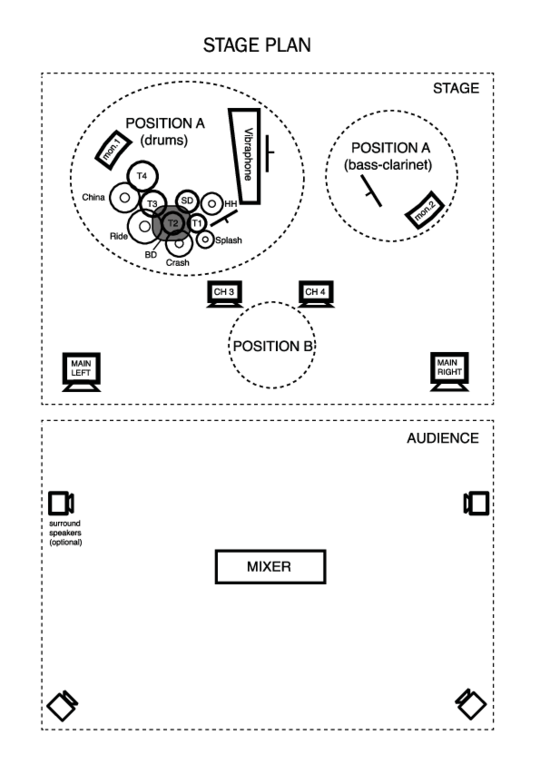

“IT” by Pierre Jodlowski covered the topic of technology addiction perfectly. It is a piece in which the musician plays along a tape, which seems to command his actions. The first half of the piece requires the percussionist to learn a certain set of physical gestures or actions, which are later on organised in constantly growing in length sequences. Those actions are then to be performed in perfect synchronisation with the tape. Please find the instruction pages of "IT" in the attached document:

The nature of this composition allowed for its cross-disciplinary interpretation, as it already includes movement as a core element.

“IT” provided the musical and dramaturgical material for the first half of the performance, as it also served as inspiration for the opening of the show, which included audience interaction. (Please refer to Chapter IV. “Premiere and Touring” for more information on audience interaction in “Inseparable”)

The idea for a second composition was Rebonds A by Iannis Xenakis, arranged in a duo version. As this piece holds strong gradually unfolding power and is built upon ever growing in density phrases, I found it a suitable one to be interpreted as a musical conversation between two players and give a strong base for a choreography to be created along to it, leading to a powerful and cathartic ending of the show. However, this idea got changed early on in the making process, as you can read below in Chapter III.1.

4.The Muziekzomer2 Residency

The opportunity to even begin shaping all of these ideas into a performance came from the invitation of the festival Muziekzomer Gelderland to be their artist in residence for the year 2023. I was provided the freedom both finance-, as well as facilities-wise to create, and the support of a professional team that helped me make this one, alongside three other projects, come true in one summer.I received the initial request, as well as support in the first stages of putting all of my ideas above together by the Artistic director of the festival. The festival production and marketing team, as well as a personal producer, helped with the practical side of making such a production come to reality. I was put into contact with Rene Spierings, who became the director for the show, with whom I continued shaping the performance from idea, through rehearsals to premiere show. Throughout the creation process, I had regular meetings with him to plan the process and make sure that he had a broad and deep overview and knowledge of the progress, so he could help me with it. As this was the first time I was undertaking such a project, his presence, experience, brainstorming sessions and much more proved to be vital. (In chapter III. “Rehearsal process” I mention multiple ways in which he contributed to the process)

5.Finding the cast

Thanks to the nature of the project, my aim was to find flexible multifaceted performers. I was seeking people who are inclined to experiment with other disciplines, feel excited being challenged to leave their comfort zones and have an active and creative mind.

For both creative and budget reasons, I decided to seek dancers-choreographers and musicians-creators, as I aimed for us four to make the show ourselves. Furthermore, with a smaller team, I believe one can achieve a more intimate connection and a simpler communication that would help in creating the content altogether as a team.

I knew that contemporary dance is the discipline that will provide movement artists most open and flexible. As soon as I knew who I was looking for, I began a process of finding the contacts and choosing the people. Below follows a description of the process.

As I was following a Master specialisation with HIIIT3(at that time Slagwerk den Haag) and one of my teachers in the Royal Conservatory was Niels Meliefste, I saw an opportunity. The teacher in question works together with the dance theatre company Club Guy&Roni4, located in Groningen. This company has an academy, called Poetic Disasters Club5, where young dancers apply and follow an internship and training in the style of the Club for one year. This academy was my goal.

I reached out to Niels and asked him for his thoughts and help. He sent me the contact of Roni Haver (one of the two choreographers of the Club). The rest went rather quickly - I quickly had an appointment with her in Groningen. I prepared a short presentation of the idea I had and my questions for her. The meeting happened on January 25th 2023 in Groningen and went very well. She was receptive to my idea, drive and inspiration. Right away, she asked me questions that helped me think forward into the process and take the necessary steps.

I asked Roni if she had any advice for me as a beginner maker in this genre. Her response was something I followed religiously during the process. She shared that it is important to work together on both music and dance as a team with the aim to deeply integrate the two disciplines.

After our meeting, from Roni I received the contact of four dancers that have been part of previous editions of the Poetic Disasters.

Once I had conducted a small research on the names, I contacted them with the information about the project and appointed short meetings to discuss a potential collaboration. The meetings were taking place online together with Joao Brito - an artist, percussionist, maker and fellow student at the Royal Conservatory. I had approached him earlier in the year with the invitation to collaborate on this project with me. Each dancer was interviewed individually. Finally, unanimously Brito and I chose two of the four dancers that felt suitable for the project and were available and excited for collaboration. The two dancers were Zaneta Keşik and Olympia Kotopoulos.

Rather soon though, Olympia contacted me with the realisation that this extra project would be too much for her to handle and politely declined, offering me another contact of hers that she regularly collaborated with. I decided to trust her judgement and directly contacted him with the project description. This last member of the cast was Matija Franjes.

I chose to mention Olympia here because she offered to help us at any stage we might need her and in Chapter III.3 I mention the feedback we received from her after sharing the recording of our first run through at the conclusion of rehearsal week two.

As soon as this change happened, the cast was created and consisted of Zaneta Kesik and Matija Franjes as dancers and choreographers, Joao Brito as a percussionist, sound designer and composer, and myself in the role of a percussionist and dramaturge.

Looking back at the recruiting process, I notice that I had to persist and seek for all the contacts myself. Rather often I find myself inviting friends or colleagues I am familiar with to join a project of mine but the extra effort of seeking the right people provided a sense of better understanding of myself, the process, the people I was involving and a clearer, broader and more critical view over the project. Additionally, reaching out to a new discipline provided new professional contacts and opened a new network field.

6.Preparation

The moment I had a team, an idea and a schedule felt like a checkpoint. I realised what felt like the most daunting moment had come. I was faced with the task of creating the content of the performance. It was the first time I was going through this process and fear was certainly part of it. Luckily, excitement was equally present.

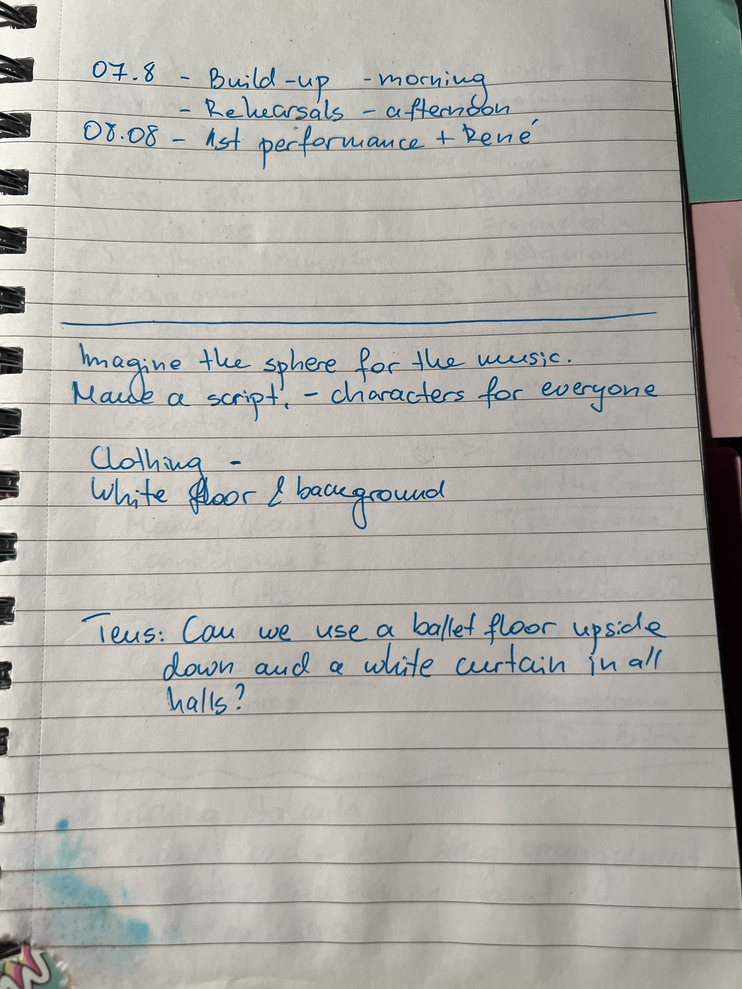

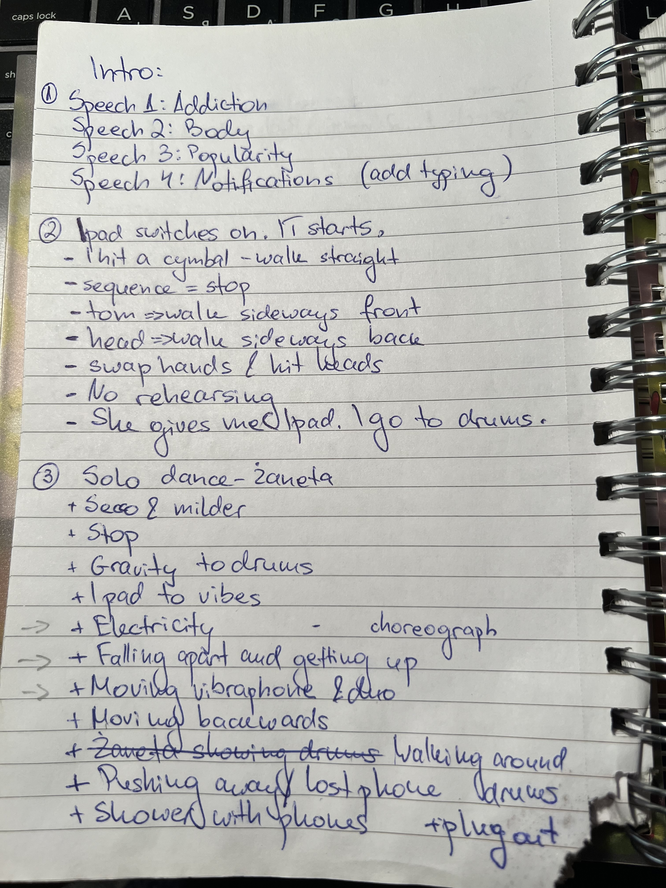

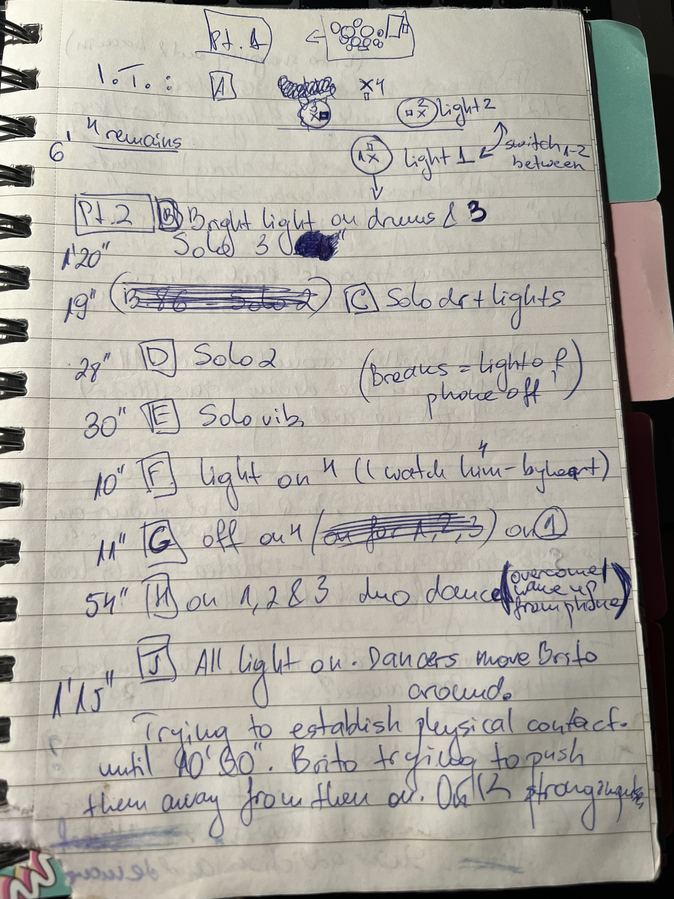

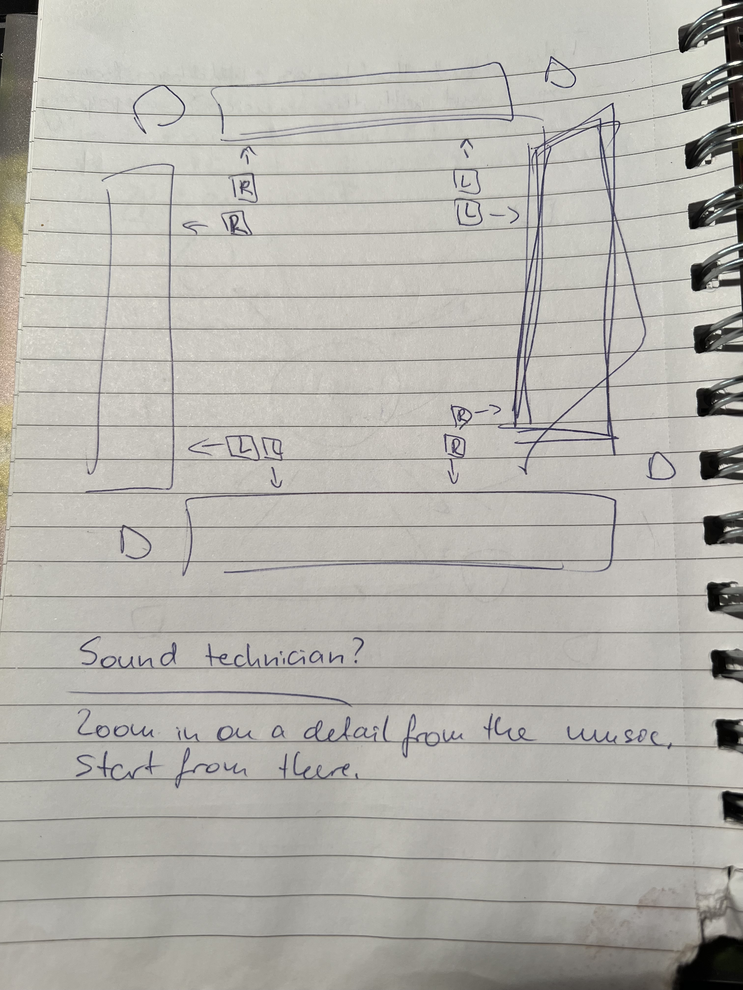

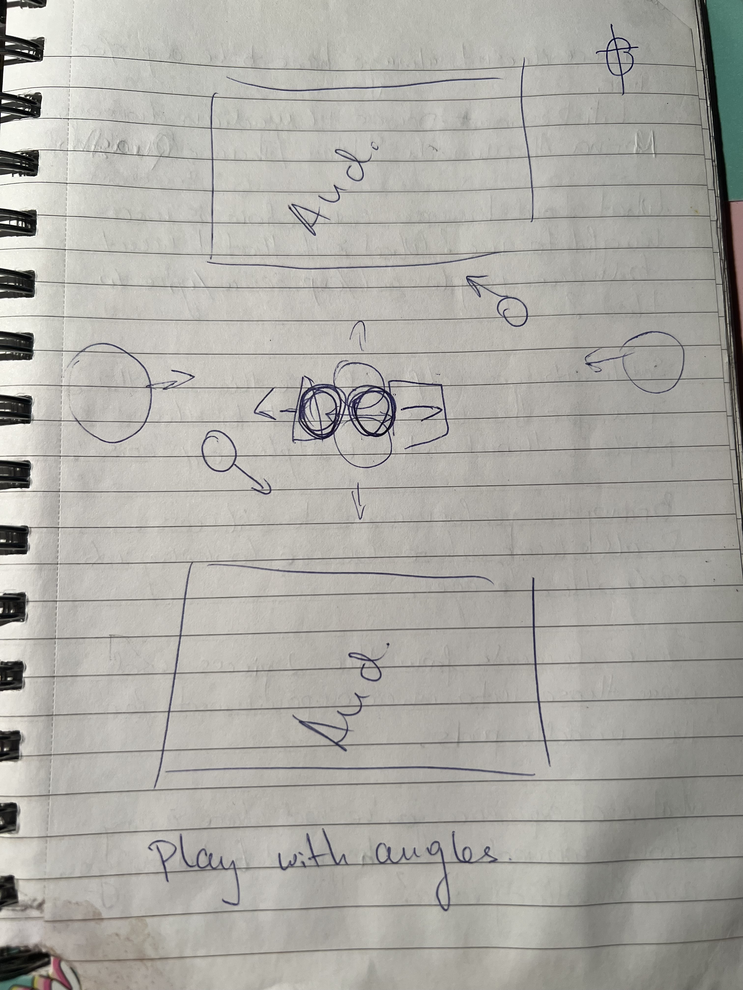

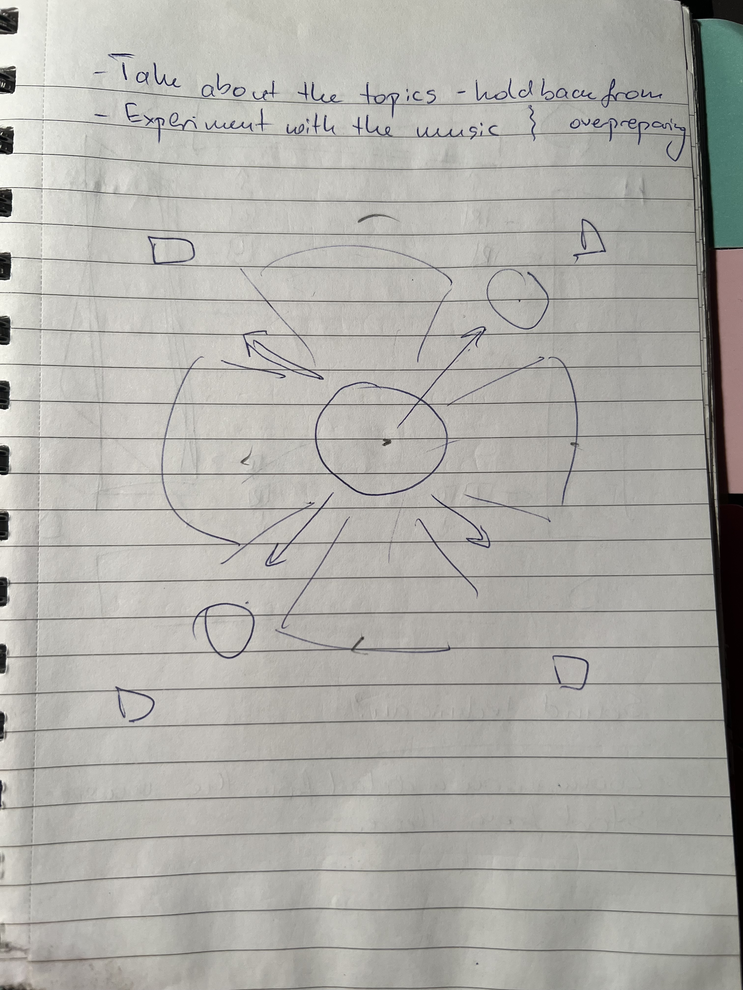

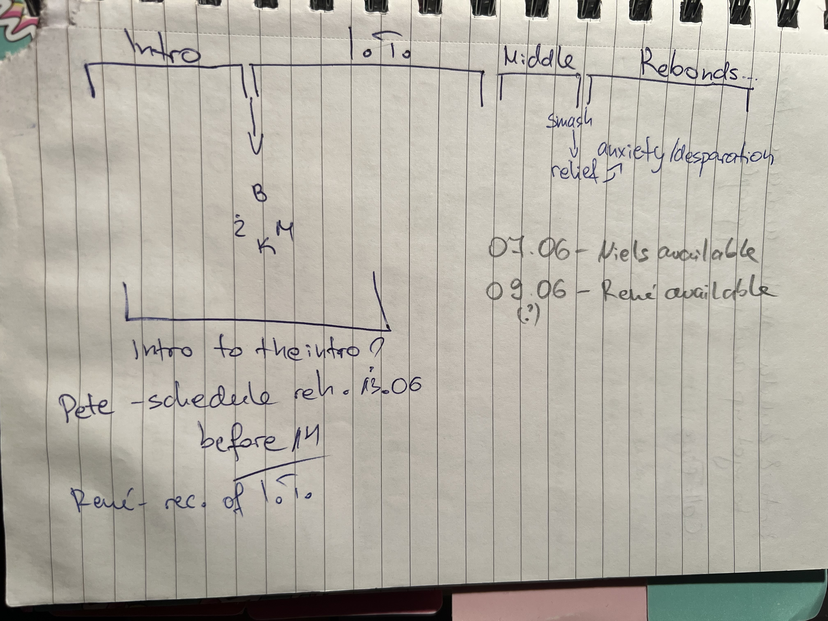

At that moment, I was involved in another project outside of the Hague. We happened to have plenty of free moments in between a number of performances every day. The weather was sunny and we were performing at an outdoor festival. Unknowingly, having a structure for the day, my basic needs covered, good weather and restricted free moments when I could sit down and work on Inseparable, provided me with the space I needed to get creative. In each longer break I would sit down somewhere on my own and use the one starting point I had - the composition IT – to help me start building material. In an afternoon I managed to build a structure and a clear story line throughout the piece. (Please refer to the photos for a copy of my worn survivor notebook pages from that day)

Of course we ended up changing a lot of it throughout the rehearsals but it was a strong departure point for the work and provided me with some more comfort, going into the first meeting with the cast.(Please refer to Chapter III. “Rehearsal process” for the development progress).

Another strong moment in the preparation period was a brainstorm session that I had with a colleague at the conservatory. I needed a second person to structure my thoughts and bounce ideas off of. At that moment I was busy with exploring the possibilities of changing the audience positioning in the venue. Earlier, in the first year of my Master degree, I joined the elective “Performance and Communication” in which we explored the (re)positioning of an audience and how that can affect the connection to the artists and the final experience of a performance. Due to the unusual nature of the collaboration, the involvement of stationary instruments and the pre-existence of technical amplification and light requirements (please refer to photo), the alteration happened to be challenging. I ended up with a number of possible audience positions (please refer to photos for examples) which were depending on the technical possibilities but after a discussion with the festival it was clear that that is not a possibility for the venues we were to perform at.

Despite the moments of inspiration and my efforts to come up with as much material as I could, most of the structure and content ended up forming from the collaborative work with the four performers. It would have been impossible to imagine and create the vastness and depth of the final product on my own. The inspiration and experience wells that all four of us were, allowed us to create something bigger than our individual abilities.

Rene on the importance of preparation: “You were very well prepared. You knew what direction you wanted to go. Sometimes we had to find some ways in the direction you choose but you were always very adaptive for every step we made.(...) For that reason, it was easy working with you. (...) The direction you choose has to come from the performer or the creator and then the director with a birds eye view can see. (...) You have to have an idea and it can change until the premiere. Even then, it can change because sometimes you feel it doesn’t work. (...) You had pretty clear (and we had a good frame on the music piece), so that was clear. The basic idea was addiction and that’s what really triggered me because it’s also (for them) a big issue nowadays with a lot of artificial intelligence and all. (...) Everything you do in theatre you have to think through. What’s possible and what’s the skills of every person working and try to get the best out of everyone. That’s what you did. You took the role of leading the pack. (...) We have a direction, within which we can change. You know that the people who are creating, they co-create and they leave each other enough space to co-create together and then you come to the next level. That’s what happened in this project.”6

6.1 Setting material before the departure point

Looking back at this moment now, a question arises. To what extent is it useful to have prepared ideas and set material before the departure point of a project, be it a first meeting or a rehearsal?

I remember during the meetings with Rene that I had loose ideas or rather pictures in front of my eyes but I could not see them clearly on a stage, in a setting, with development. Everything was rather a feeling, a colour perhaps that I could sense in my imagination and try to put into words. Already then I wondered how much of the content should/can I come up with on my own.

At first, looking back at it, I supposed that during that process he’s been asking me about the content not so much for the story line or concept but rather to push me to envision and set the practical aspects of the project - the number of performers, the amount of instruments, technicians, length, requirements for rehearsal and performance space, purchasing music and its rights, etc. - all the practical elements that are necessary to give us the chance to create a piece. This is what the production team needed to take care of and it depended on me to provide them with the necessary information about it.

After I conducted the interview with Rene, though it turned out quite the opposite. Here is what he told me: “Practicalities are always in the second spot. The artistic idea is always leading. Always! (Something) practical you can eliminate during the process because you can always say “Oh that’s impossible” but you first should try it. That’s very difficult. That’s why we need a financial director. Always in every company the artistic and financial directors always clash. For me it’s “sky is the limit” but the truck is only that big and you have to deal with it. There are some borders. But you should always start with a big idea!”7

It is intriguing how intertwined the practical and creative aspects of a performance are. Having the space to create/experiment is dependent on the availability of facilities and to find the right conditions you need to know what they are, which comes from knowing what you are about to create. It is a closed circle.

This leads me to a conclusion that on the one hand, to find the space (both physically and mentally) to create and seek out of the box, one needs to initially put themselves into a box (define limitations), so they can have a point of departure. At that point our mind is the only constricting element (the broader one can think - the bigger the box becomes), if we leave the question of budget in the background, that is.

On the other hand, gathering four highly creative minds in one room provides an endless source of possibilities. Through improvisation and experimentation, eventually the group collectively comes to conclusions for which material feels most right to use for conveying the message it aims to. A remark I received by Matija during the interview shows: “You already knew what you were going to make. It very often is not the case when people come and start working on a project. It was very helpful, actually because you were already very clear with things you wanted to do.(...) Making dance, very rarely we work with any kind of score. (...) What we do a lot of time is we talk a lot about the subject and then we go into the space and try to find either a practice or some sort of exercises that relate to the subject that we are talking about.”8 Upon asking the director about his opinion on this matter, he said: “(Matija), he immediately works on the floor and is very creative. So, you have very different people and have to communicate in a very different way and the result is very different.”9 (Further on this topic at the end of section III.1)

“Dancers learn nearly entirely in groups and do not usually practise individually outside the studio much, whereas musicians learn mostly through one-to-one lessons and individual practice, and less so by playing in an ensemble.”10

In the end, I believe I managed to achieve a good balance for what was required by the festival and to remain flexible, leaving enough space that even ideas that felt “set” in the beginning were easily transformed or entirely left behind if there was a convincing reason for that. (Please refer to Chapter III.5 for a list of ideas that were constructed, cut out, transformed and used throughout the rehearsal process)

7.Budget

As briefly mentioned earlier, the budget is a very big factor to how big or small a production can be. Depending on it - your idea can be as big as you can imagine - it won’t happen, unless you have the money for its size. Once you have shrunk your idea to the constraints, any change you’d like to make or add needs to be once again, according to and fitting within the budget.

“If the bag of money is limited the amount of problems you can solve is also limited and that’s something I can talk to you (the creator) about because it doesn’t really matter where it (the compromise) comes from but at some point it either has to come from the concept and desires or it has to come from finance.”11

I realise that money is what enables us to create a project in the first place (as we all need to make a living and have a limited amount of time to spare for work) but it is also what can constrict the creative process so holy to a creator. Short amounts of rehearsal and preparation time may push artists to be efficient, quick, adaptive and practical, which can all be positive consequences but the creative mind also needs a sense of freedom and timelessness to be resourceful.

Those moments are what I find artistically deeply valuable. The sense of timelessness and shared creativity with other artists is what develops me as an artist, as a person and together with that, pushes the work field forward. Once the mind is free to fly within the creative timeless space, that is when ‘the magic’ happens, we can tap into the effortless source of creativity and innovative ideas can be created.

To come back to the topic of budget, I feel that the way projects, such as this one get funded may constrain creativity and thus often result in a poorer artistic value of the products, all the while providing the source of income, enabling us to create and work in art for a living in the first place.

“I know that my personality is that I don’t like changes. I understand I have to work on that. (...) It’s also a skill. Sometimes it’s also fun (…) to find a solution. I do like that part of problem solving. You sometimes have to kill your darlings.”12

“I love last minute changes. I really really love that! You realise sometimes it can be frustrating but it gives me an extra adrenaline (…) excitement… (...) I work better with pressure. I just do it and I know I am going to do it nice.”13

At the end of the day, I choose to turn to myself for solutions and seek the best ways to adapt to the conditions. I seek for the ways I can be most efficient in my work, using time limitation and pressure as a motivation source, all the while training myself to tap into the creative space in question despite that pressure.

III. Rehearsal process

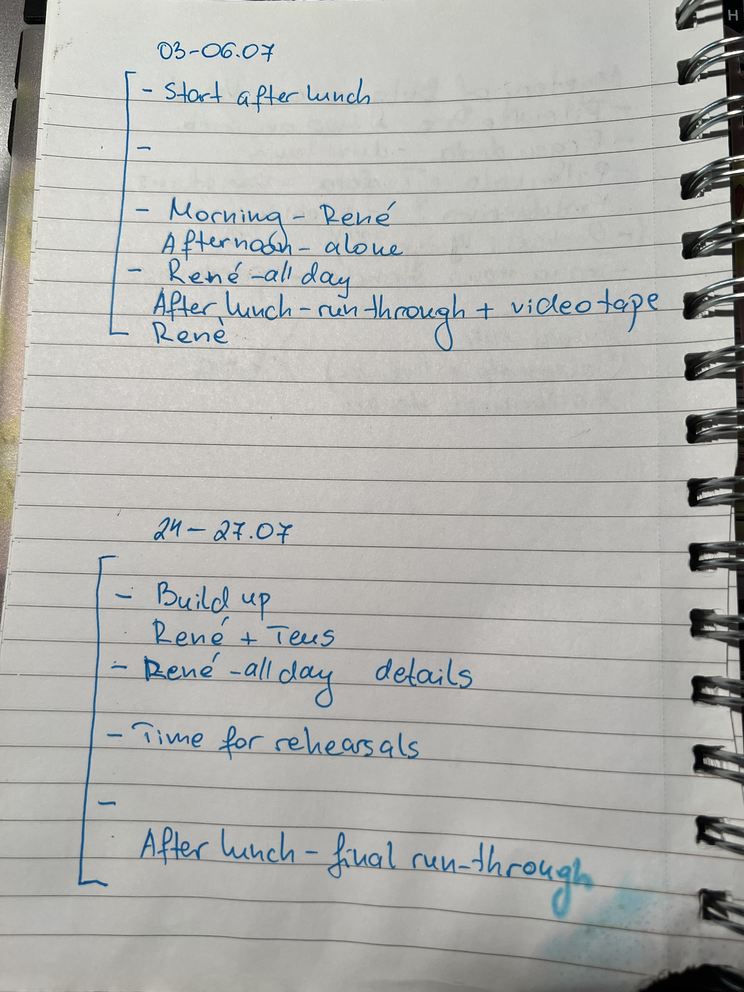

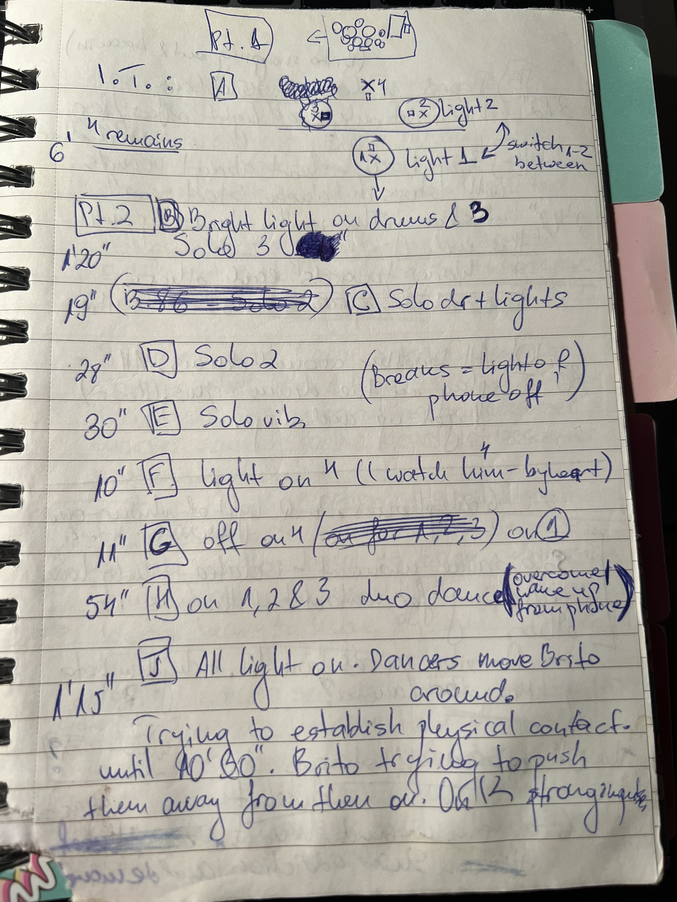

The rehearsal process spanned from the first meeting on 31.05.2023 to the premiere day - 08.08.2023. It consisted of four parts, namely:

1.1. First meeting

2.2. First rehearsal week and prototype

3.3. Second rehearsal week and first run through

4.4. Third rehearsal week and montage

1.First meeting

The first meeting day took about three hours. During this time I planned for the team to meet each other for the first time, have a short introduction round, then to have the idea and outline of the show explained by me and questions and ideas for an end.

Already at the very beginning we were faced with an obstacle. One of the members had a delay of an hour with another appointment and the rest had to wait for them to arrive. That was an unpleasant situation, as it was not an option to explain the concept to the rest and have one person stay uninformed and unknown to the rest of the team. Luckily, we all decided we had time and waited for the member to arrive.

At the start of the meeting we had the short round of introduction and I began explaining the framework of the show, together with the musical content planned, my dramaturgical ideas and introducing the rest of the team that was to join us later (both technicians and director). (Please refer to photo for the structure I presented on that day)

During the presentation of all the material I had already built, I aimed for building a picture of the framework before diving into details. This was a good strategy to keep things clear and stay on track but thanks to the curiosity of the rest and their aim to understand me better, I received plenty of questions right away. Of course that was to be expected and very welcome. I strived to stay away from presenting the material as a lecture. This was, after all, a co-creative process from day one. The inquisitiveness of the team took ideas I had mentioned right away into a playful state of development, critical viewing, brainstorming for new ideas and at times direct disposal of old ones.

For example, the piece Rebonds A by I.Xenakis seemed like a good idea in the first place. As I outlined the show and delved into some more musical detail the outside perspective of Joao Brito provided a good point that the composition is indeed strong with its musical material and development but the acoustic drums sound was too far away from the rest of the musical material we were about to make. That included electronic music tracks and the pre-existing track of IT. The acoustic nature of this piece was not going to fit, so we decided to drop it right away and create music of our own on the same principle of continuous development and material expansion.

A second example is that I had the conviction that we needed click tracks to be able to synchronise movement and sounds from the tapes that were to be played, as the idea was for them to include notification sounds as cues for specific transitions, that were meant to occur simultaneously with the sound. After a discussion with the rest of the cast we got to the conclusion that that would be useful but rather impractical.

During the rest of the meeting important questions were asked, such as “What is a standard rehearsal day schedule for a dancer?” “What do you need to have in the rehearsal space?”

At the end of the meeting, by suggestion of Joao Brito, we distributed tasks to each member. All of us needed to write the text that eventually became the middle section of the show. The two of us with Brito needed to create the opening track of the show in the coming week. I needed to find a studio available for the amount of hours we needed and suitable for work with movement. That last element was something that challenged me. I knew of a number of musical studios but no dance studios (as I had never before needed to use one), that had enough space and a clean floor. Luckily that is when Rene came to our rescue. He offered us the studio of the percussion group Percossa (whose artistic leader is Rene), which rehearses in the Hague as well. They work with theatrical performances and therefore also had a mirror wall, which came in handy for the learning of some group choreography.

It was reassuring to see how often the rest of the team recognized and perhaps associated themselves with what I had experienced and was presenting as a dramaturgical line for the story. As this topic is so relevant for today, it was easy to recall moments in the crew’s memory when they had experienced the states I wanted to convey with the music and movement.

We also coined a number of keywords for the different sections at the end of that day – uncomfortable, provocative, triggering, isolation, loneliness, longing for contact, catharsis, overcoming, reconnection.Another positive sign was that the group was excited by the project, worked well together as a team right away and were looking forward to jumping into the creative process.

- A remark to myself after that first meeting:

- Both Brito and Matija expressed that they relate easier to visual explanation of the material. For example, I drew the structure of the show on a board as a starting point and notated a number of checkpoints and positions. Brito requested that I draw a tension graph, representing the different checkpoints and how the energy is to evolve throughout the performance. That helped him envision the kind of music he needed to make. It is better if I can explain an idea both visually, as well as with words.

2. First rehearsal week and prototype

I will begin by stating that the first rehearsal week went nothing as planned. Here is how it went:

Everybody was on time for day one and the progress that day was great.

The first thing I had planned were a number of get-to-know-each-other games. I thought of doing those games at the first meeting already but this was a much better moment. The games were of a shared physical nature and were focused on building on areas, such as:

- - Breaking the ice

- - Building mutual trust in the group

- - Getting out of our comfort zone

- - Exploring movement (in couples, as well as in a group)

- - Letting go of control

- - Cooperation

Those games let us open up to each other, bring us to a relaxed focused state and build a playful atmosphere right away.

Following, the work on building our performance of IT began and covered the rest of the day. We took the ideas I had outlined in my notebook from back in April and began exploring them. Later in the day, we learnt the choreography, written by the composer for the opening of the piece. The opening of the piece IT includes pre-choreographed gestures that need to be executed in sync with a tape. Those gestures correspond to a number of command sequences that are firstly presented by a voice, after which executed by the performers in sync with corresponding sounds, assigned to each movement. The performers execute a sequence of rhythmical gestures, as if they are playing on an imaginary drum set, accompanied by a sequence of corresponding drum set sounds.

(Please see the photo-video example comparison of paper to action from that day)

At the end of the day one of my teachers happened to pass by the studio and we showed him what we had. We had not yet made any choices, even less so began reasoning those choices and having what we presented be questioned right away felt rather vulnerable. Yet, receiving feedback on your process can, more often than not, be useful.

The day was concluded as a successful beginning of the process. That same night I received a call from Matija that an old injury of his has resurfaced and he is unable to get out of his bed because of the pain. He was not able to join us for the rest of the rehearsal week, nor perform at my First year’s Master examination concert.

On that day the three of us with Zaneta and Brito had to decide on how to continue. I decided I would like to reform the performance into a duo for this week and work one on one with Zaneta. Brito assumed the role of the sound designer and composer only for the rest of that week.

With Zaneta, we spent two days coming up with many ideas for movements, shared moments of intertwining the arts, choreography, meaning, experimenting. (Please see page from notebook)

By the end of the week we could present a complete performance of the first half of the show (from the opening of the show to the ending of IT). Three run-throughs took place. The first one had Joao Brito as an observer. The second and third ones – Rene Spierings, as in between them, there was a two hour long working session. During that session ideas and decisions were challenged. We worked on:

- - The clarity of the intro by Zaneta coming on stage from the audience.

- - Executing the beginning of IT as perfectly as possible.

- - Movement, as well as instruments specific work for both of us (with special focus on the sections, in which we were both playing on an instrument or were both executing a specific choreography simultaneously)

(Please refer to video for a compilatoin of examples from the run through with Rene)

Following here, I am elaborating on the insight I gained from the work we did to prepare the moments of crossing the arts. I have structured the information in two paragraphs. One for crossing into music (Zaneta playing an instrument) and one for crossing into dance (me performing choreographed movements).

- - Crossing into music:

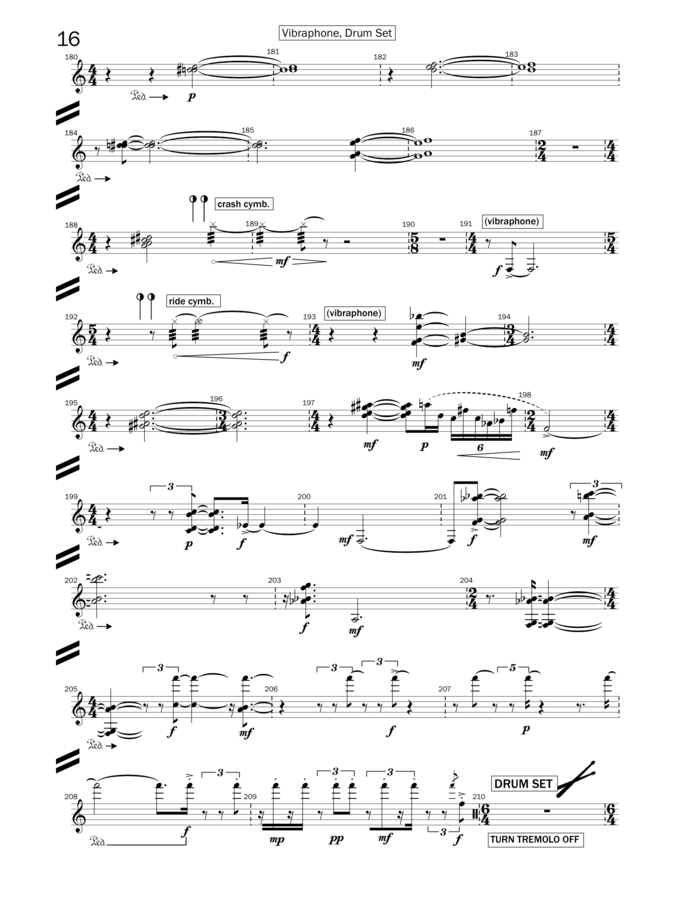

The moment we had to play the vibraphone together, there were two main tasks. One was to remember the notes (as we split four-note chords amongst the two of us with each one playing two notes at a time) and the second - to remember the counts of each measure. The meters were changing nearly each bar and were often irregular too. The place in the bar, where a chord needed to be played, was also always different. (Please refer to the score page of the vibraphone section)

“It was interesting to see how different our brains work. Also, mine and Matija’s already. (...) I was making a choreography out of it. (...) I think Matija was more understanding with the tones. (...) For me, my side was the correct side.(About counting) That was super funny because I was quite confident in the beginning and you were counting and I was like “whaaaaaaaaaaaat? Maybe not.. Maybe not…” I took it really from the choreography and memorising the movement through the whole instrument and also the sound that I can remember and get used to. I remember which place has which sound. (About playing the drum set) In the drumset that was also very much about the movement for me.”18

How we approached this process was that first we learned the sequences of notes. That part went rather well.

After we had the notes correctly remembered, it was time to add the rhythm. She asked me to help her remember the counts of the bars as they are (I remark this is an entire page of music with each bar in a different measure and playing on a different moment of the beat every time). We attempted that and rather soon got to the conclusion of it being awfully impractical. There was no chance of us remembering the bar counts and playing each chord together with eventually no counting out loud. Frankly, I did not want to remember an entire page of oddly changing irregular meters either. We had decided to learn the music entirely by heart, as the theatrical aspect of the performance would benefit greatly from that.

How we ended up solving this situation was that I wrote down which words from the audio tape corresponded to which rests or notes in the score. Using those words as aural cues, I would anticipate and cue the moments we had to execute the chords. All Zaneta needed to do is know which notes she had to play next and follow my lead.

This solution was simple and effective (including for the moment when eventually four of us had to perform this section). It challenged me out of my comfort of reading such complicated compositional sections and I had to find new ways of listening and connecting with a tape recording. Putting myself in the place of a dancer was a good trick to think “out of the box”. They don’t necessarily read scores. They rely on their ears to contextualise what they hear and remember cues in a different way than reading a meter and imagining a pulse that is not necessarily there. Eventually, I used this method for learning the entire composition by heart, including the moments I was playing on my own.

Throughout the process of rehearsing with Rene as a director, a second layer – a movement layer - was added to this section on top of the musical one.

The idea he had was for us to move in a manner that I deem similar to figurines playing the bell of a clock counting off the hour. Those figurines move in a mechanical way, aiming for the stroke, executing it in a separate movement and swiftly retracting their arm back into starting position, ready for the next stroke. As the show deals with the topic of becoming un-human/cyborgs, robotic movements were a strongly present element in the choreography for the percussionists (mostly for the duration of IT). (Please refer to video for better visualisation)

The next section, where the dancer had to play an instrument, was once again in IT. This time it was happening around the drum set. What I did there was once again to alter the score in such a way that it would be little noticeable sound-wise and yet much more simplified. (Please refer to copy of the score page) How I altered the rhythm to help Zaneta play with ease was instead of playing rllrllrllrll (r=right hand; l=left hand), we changed it to simple alternation (rlrlrlrlrl). The effect of fast alternated notes ended up sounding nearly the same, perhaps even better as we were playing on two different drums at the same time. Our approach for that section was mostly the same as by the vibraphone – we learnt the aural cues of the tape and the words or noise signals that we had to search for. We would shift to a different drum for each new segment. This time I did not need to cue the entrance as much. Here choreography came into play, as we were physically shifting from one position around the drums to another. The time to reach the next drum filled in the rests in the score. Via repetition we, both physically and aurally got used to the timing of the tape and movements. This was a spot, where choreography and music were inseparably intertwined. I needed to remember where to move to each time we played a new drum and that activated new ways of thinking and contextualising performance for me.

- - Crossing into dance:

There were a number of other moments when I had to work with choreography and movement. As previously mentioned, in both examples above we were dealing with the combination of movement and music.

One place where that occurs is the very opening of IT. As previously mentioned, the choreography is pre-written by the composer and explained on the score. Here again the two disciplines came into each other and this time interestingly so in a number of layers. As a musician and percussionist, from a score, I learned the movements the composer had designed. Next, I taught the choreography to the dancer. She in return contributed by making the movements more characteristic for the style. An audio tape was “commanding” what movements to do and yet through listening we had to learn the sound cues and timing for each movement/sequence. The skills we both have outside of our disciplines came in very handy at this moment. The same goes for the later stages of rehearsals when all four of us were learning this section. (Please refer to video of four of us performing the opening of IT)

On top of this movement and musical material, we created an extra elaborated choreography that added to the story we wanted to tell throughout the piece.

Finally, a major moment for me crossing into the dance discipline was the fact that we decided to make all of my movements while playing robotic and machine-like. This was a learning process for me all the way until the premiere of the finalised performance in August. I experimented with this type of movement when I was practising on my own, as well as at home, doing any regular chore. I watched videos of the latest human-like robots. I tried finding the characteristic stop and go motion in robots’ movements, imagining my “brain” calculating my next action and making the look of my eyes empty, if not even a tad unfocused.

This character is something we worked on together with Zaneta and Rene. Joao Brito also needed to take this role of a robot, playing on a vibraphone. Another characteristic movement we had to learn was imitating the shaking motion of getting electrocuted.

All of these and more were elements that Zaneta (and later on Matija) had to teach me (and eventually Joao Brito), while I taught her how musicians think via a score and how to play on both a vibraphone and a drum.

The theatrical elements of the show were closely and with a sense for detail coached by Rene Spierings.

Altogether, this was a strongly developmental process for both of us.

As mentioned above, Brito took the role of a composer only for that first week. That did not mean that he worked isolated from home or had any less pressure. Most of the time when I wasn’t rehearsing with Zaneta, the two of us would be planning the audio tape, leading into IT’s beginning. We spent time brainstorming what words, phrases, information we would like to hear in that tape. We sought quotes from speeches of key figures, who have contributed to the development of technology. I wrote and recorded a text, introducing a figure that is addicted to their phone. We then, with the help of effects, modified the voice such that it was unrecognisable and that it could belong to either gender. Joao spent a lot of time with the two of us, adjusting the tape as we needed it and composing alongside our process with Zaneta.

During that first week, despite the lack of two members, I was still working on ideas for the quartet version and writing down scenes (In the slideshow some example pages). In these moments, as mentioned before in chapter I.6.1, I felt the pressure and need to know exactly what I wanted to achieve even before we had experimented and brainstormed as a team. Perhaps the time pressure and circumstances were helping put some extra pressure on working quickly.

- A remark to myself:

One major difference that we noticed at the sound check before my exam was the different approach and use that we give to it before a performance. What a sound check would mean for a musician and more specifically for a percussionist is to set the instruments in the correct place, make sure everything I need is present and in the correct place, check the sound and light (if necessary) and perhaps play the most difficult sections (especially if in an ensemble setting) to make sure everyone can hear and/or see each other and feels comfortable in their spots.

The difference to a dancer is that they need to feel all the space they have on a stage, as it is always different to the rehearsal spaces. They need to make sure they all have the same idea for spacing their movements, especially if in an ensemble setting and that they can hear the music well everywhere in the space, while moving.

The conclusion after our sound check was that there was too much time spent on designing the lights with the technician, just enough time spent to set up, very little time spent on sound checking anything and way too little time spent on spacing and rehearsing with Zaneta (as the performance happened a few days after the rehearsal week with no time of coming back together in between). She felt rather rushed and as if what she needed was not met. I did not predict the length of the work with the light technician, as we had met before and spoken about the different scenes and cues he would need to look for. Next time, despite the initial meeting with the light technician, I will make sure to either already work in more detail with them or give a detailed cue list with technical specifications to avoid losing too much time.

Unfortunately, at a later performance of this same segment in a setting with three performers, the light design once again took up most of our on-site rehearsal time.

Until the second rehearsal week I needed to make the choice whether to keep Matija in the group or not. With him being that late for the first meeting and leaving for the entire first week of rehearsals (although he could not help that), I was losing my trust in him.

We had a number of conversations between the entire team and we finally decided to continue our work with the same people. He made promises that he will take care and make sure that his back problems don’t occur once again. In the end, I am glad that we did continue working together, as he proved to be a strong and contributive figure in the creative process. “When he’s on the floor he gets ideas. He immediately works on the floor and is very creative. That’s different people! But you made the right choice to keep him. We need them (those kind of people) in the theatrical profession.”19

3.Second rehearsal week and first run through

Before the kick off of the second rehearsal week, a meeting with Rene and I took place. We planned what needs to happen until the premiere day and when. That helped bring clarity to how much time we have and how we need to pace ourselves through the rest of the days. (notebook photo of planning)

On 03.07.2023 rehearsals with the complete cast resumed. We recapped the material we had until then and began experimenting once again, this time taking time to simply create and not yet work on material right away. The most rehearsed part turned out to be the opening choreography of IT. We did that every single day, since it needed to be perfectly synchronised with each other and the tape.

The rest of the choreography for IT went pretty quickly. We left the intro with the audience to be developed in week three. I was left with the impression that it was on the late side to create it then only but when asked during the interview Rene mentioned:

“We could go further in the beginning/the opening. There was a lot of empty theatrical space we could use and by starting the performance like how we started now with calling and sitting in the audience. The people really liked it and they were classical people. I really like this tension. Go further! Be rude! Make it very uncomfortable for yourself but also for the audience. That’s a point where I would have liked to have more time in the beginning that we could do more performances with the audience and then try to (find) what’s the maximum we could do to get very uncomfortable. (...) We couldn’t do it earlier because the rest of the content wasn’t finished until then and then there’s always one or two spots that (you think) you should have tackled earlier… but you have to also feel it. When I was in the hall I felt it and then you incorporate everything - the audience and their reaction - then we have to be very sharp on it.”20

Because of time constraints and lack of technological skills and availability we dropped the idea of a second layer tape with notifications and buzzing devices around the audience. The idea of Brito being a central character in IT also dropped. He joined me at the vibraphone and the dancers mostly improvised on the spot every day, each creating a narrative for themselves and for the group picture. The ending of the piece was planned in a certain way until the first feedback moment with René that same week. A drastic, rather controversial suggestion was made and that became the pinnacle of the entire show. To keep the suspense and chronological order of the story, I will postpone sharing what that suggestion was until the end of this section.

Most of the work left now was for the creation of the second half of the show. That included a vibraphone piece excluding the dancers (as that is what we eventually decided upon), the intimate middle section and the final build up to the end.

The composition we ended up choosing for a vibraphone duet scene was Apple Blossom by Peter Garland. The piece is originally scored for four players on one marimba but we managed arranging it for two on a vibraphone. It is a minimalistic piece, the musical development of which unfolds slowly and closes relatively quicker, like a blossom. This piece felt like a suitable one for a long restful moment after the storm we will have created. (Soon you will find out what that is.)The other role of this composition is to take the energy down and bring people back to a calm state, so they can comprehend what we called the “Speaking section” that followed.

Instead of having our voices recorded (or we were also discussing wearing headsets) and introducing ourselves in the beginning of the show, we let the speech idea unfold in the middle of the performance. The texts that were one of the tasks to send three days after the first meeting on 31.05 turned into the material used for the creation of this section. A short back story: I enjoy working with text and reading and have done so since I was very little. I even won a creative essay writing competition at the age of nine. :) I did not take on a journey of developing it much yet but the moment the opportunity to create the text and find a clever and playful way to intertwine two stories into each other presented itself, I knew I wanted to be the one making it.

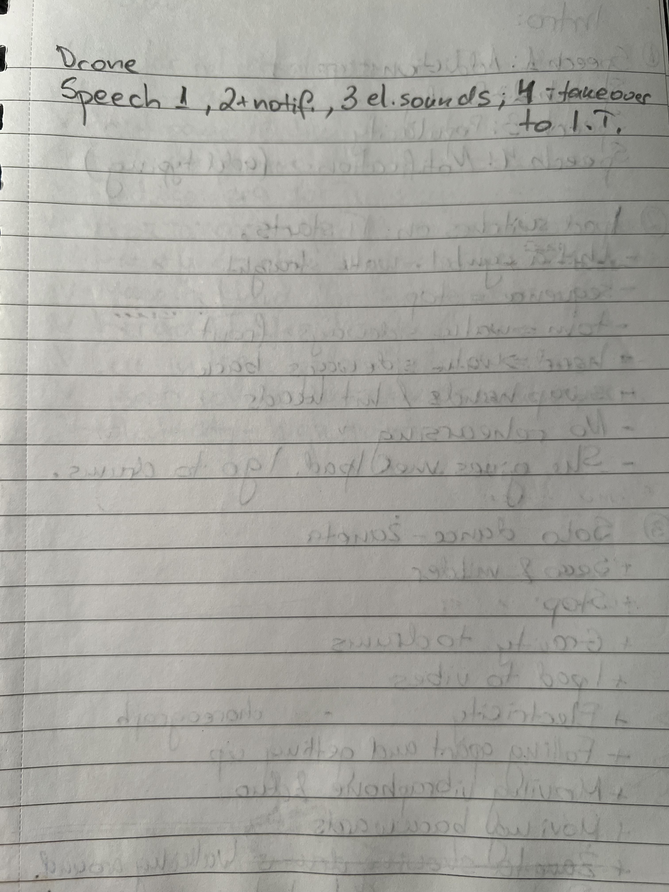

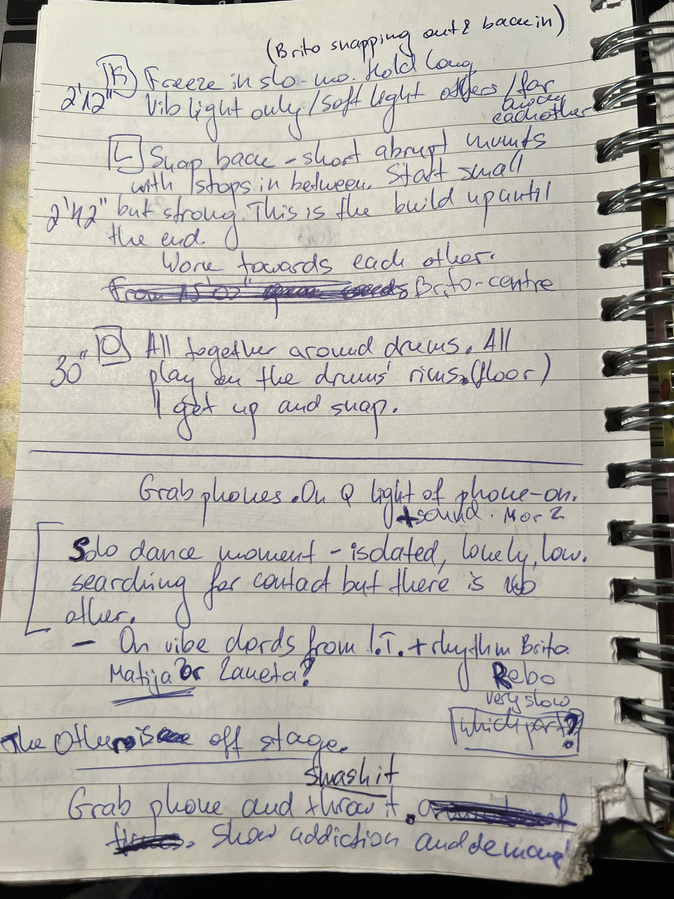

All four of us had written down experiences we’ve had related to our phones. The result was two parallel monologues/confessions, presented successively in small paragraphs by Joao and I, that gradually grew to pick up speed, interlock and eventually independently merge into one and the same word “Scrolling and scrolling and scrolling and scrolling…”

While Joao and I were enjoying taking the role of actors (and stressing about forgetting what to say), Matija and Zaneta gracefully took the role of embodying the stories we were telling. Please look at the following video, as I would not want to put this moment into words:

One may have noticed that we have the tendency to split the cast into couples for each major scene. That is actually an element we became conscious of throughout that second rehearsal week, thanks to my PIA coach Pete Harden.

“There’s a lot of one-to-one relationships (about the text, movement and about the music we are hearing). I miss a little bit of counterpoint. There’s a beautiful moment when you are destroying the drum set and you are alone in the front but you (Zaneta) have a little bit the same energy… I’d love you to be a different person at that time.”21

Oops! Here, I’ve given it away early… Well, here is what happened:

The grand idea that Joao came up with in a moment of wild creative freedom was to “destroy” (rather more like carefully take apart with the convincing acting of handling the instruments in a harsh manner) the drum set at the very end of IT. This suggestion, perhaps tossed in the air without too much thought was an immediate bull’s eye! All of us were crazy and adventurous enough to decide to do that! (Even the director - Rene. He eventually found our destroying action rather mild. Different opinions were shared by the production! I know Joao’s palms were itching to grab the instruments and put all of his energy into “destroying” them!) Now, there is a very logical pathway to how we got to this conclusion. The drum set was a metaphor for addiction for my character (a human that has become a “robot”, controlled by the voice of the IT). The symbol for addiction had to be destroyed to shake me out of the state of addiction and help me get out of that control state. (Please refer to video for this moment of the show)

Hmm hmm (clears throat…) moving on…

The flow of the creation process of the second half that week went as follows:

The four of us would get together and select a section we were going to work on. We would decide what we were going to do in that section, what needs to be created for it and how much time we are going to take making that. As soon as those parameters were clear we would break into couples (musicians-dancers) or sometimes individually and begin working. As soon as the time was up (or we felt it was a good moment) we would get back together and check in with each other on what we have so far. We would usually check how the music and dance unite and see if anything needs to be changed and proceed in the same fashion further. This way of working proved rather productive. Everyone had the freedom to take their space and do their task, while at the same time there was plenty of communication and connection between the individual activities.

Indeed, an issue that remained somewhat unspoken arose during the interviews and that was that at times we had one space to create both music and choreography simultaneously. That came in unhandy in moments when Joao and I needed to improvise for the last scene of the show and Zaneta and Matija were creating choreography at the same time. In the moments when we needed to play we were trying out structures we had come up with and generally getting more and more comfortable playing with each other (unifying our timing, our sound approach and developing an understanding of each others’ improvisational language). The dancers needed time on their own to come up with the structure of their choreography (which was a sequence) and they needed to count out loud to make sure they were executing the sequence in sync. Plenty of discussions occurred between them at that stage. Them needing to hear each other and us playing on bass drums and wooden rims in the same room was indeed unclever and did contribute to some tension within the work process. The separation of the two groups in two different rooms would have been a wise choice. I believe we began taking shifts and communicating better when the one pair needed the space for themselves for a certain moment.

An element that followed as a result of the two processes running in the same room was that we ended up checking with each other rather often and immediately tried solving too many problems at the same time. Zaneta pointed this out during the interview. “Sometimes it again felt like we were trying to solve a lot of things at the same time. (...) I didn’t feel like it was disturbing us in any way (...) because everyone was involved but that’s what I can think of about creating in the same time.”22 It was certainly possible to create in that way and this is not necessarily a bad approach but trying to work on one step at a time is always worth the try to see if the workflow would be better or quicker that way.

The section that proved most difficult to create was the ending of the show. We had decided upon creating our own music and that went rather slowly. Joao and I were experimenting and improvising on two kick drums, alongside an electronic track, which we kept and developed until the end. This section remained unfinished until two days before the premiere. The dancers also had trouble choreographing it as we wanted to use the basic idea of building on repeating patterns that evolve and grow constantly but without changing too much to create a densification of the material, slow and long build up of tension, representing transformation and finally a liberation at the very last note of the show.

“Even like next to Rene if there would be a choreographer or a dancer it would be perfect. (...) That’s always the best but if you have this guide that has some knowledge in both departments, then of course you can also take care of your own… (...) It really helps because you cannot see from the outside, so having that outside eye whose profession and the eye is specific for the movement it’s also good.”23

“Sometimes you try things and you don’t see it from outside and later you realise something doesn’t work. (…) It’s very hard to make and perform.(...)...Having a choreographer or somebody to guide you movement-wise.. Some people manage it but I find it something I would struggle with, especially when it’s with more people. It’s a very fun challenge and I think we did very well. When it comes to movement and choreo, things can go so much further and deeper when you have a constant outside eye who understands movement to give insight on frequent basis and give direction movement-wise.”24

All of this worked out eventually but I believe there is still plenty of room for improvement in the section in question. With more time, space for creativity and perhaps some very welcome outside people input, the music can become much more elaborate and virtuosic and the dance can achieve the expression of even more tension and struggle, so that the cathartic ending can feel like an even stronger release.

I believe we did not manage to achieve the goal of having the highest tension moment of the show in the very end. The demolition scene from the end of IT seems to have left one of the strongest impressions. “The scene with destroying the drums was very strong and it’s difficult to carry on from there (build higher tension).”25 It is true that united destruction and chaos do bring more tension than two separate couples, using a rather minimalistic approach to build tension over a long time span. This is something I want to develop further in this show.

I believe the further we went into this second rehearsal week, the quicker we began making decisions, as time was pressing and the first week had gone way differently to what we all expected. This is the moment I would like to go back to when we continue work on this project and question some of the choices we made.

The conclusion of this rehearsal week was the recording of the very first run through of what was then the full material we had created. That happened on the last day’s morning in front of Rene and Pete Harden. Pete happened to be my PIA (Personal Integration Activity) coach. This is one of the three pillars of the Master Programme at the Royal Conservatory and I had chosen to connect the current Research to my PIA project.

Wonderful feedback was given to us after that run. One great example of Rene generating ideas and workingon theatrical elements is this excerpt:

"I want to try if when you beat this note and then go back in a specific zero point. Every time, like you are a machine. You have this youtube movie of this electric vibraphone that’s also doing this. I would love to see that. It’s very difficult, so you have to play the 'f' and go back. If you do it with the four of you, then you are really a machine.”26

“Since you are both human when you start speaking (to Brito) You are more saying facts but you (to Kalna) ”Your bike is stolen” It has to be like FUCK!! My bike is stolen! Not like Siri: (immitates artificial voice) My bike got stolen... Go all the way!!!"27

An extra person that received a recording of this run was Olympia (as mentioned in Chapter I.5, Olympia was initially invited to be part of the cast but due to time constraints she chose to suggest Matija as a substitute for her spot) and she took the role of an experienced observer seriously! Here is the document that she sent to us a few days later with suggestions:

Interestingly, nearly all of her suggestions ended up being implemented in the final performance. Some of them overlapped with the discussion with Rene and Pete and others were new for us too.

Here is a compilation video of the first run through:

4. Third rehearsal week and montage

In the last rehearsal and montage week we moved to the premiere venue and what turned into my home for three weeks - Orpheus, Apeldoorn. That week took place between 24-27.07.2023. This was the final stage of preparing and finishing up the work. For the first time we had lights and sound designers at our disposal, ready to work with us and make the final product complete. This was an exciting time of seeing everything come together, as well as be faced with new challenges and questions.

I was not aware that we would have Theus (light) and Maurits (sound) with us for the entire week. This remained rather unclear until we all came to find each other there with more time than expected. That was wonderful and left space for both of them to get creative and experiment with numerous options for the different scenes or issues we were facing. They co-created the final state of the performance with us.

Light design: Teus van der Stelt was our light designer. Why the title designer? Because he performs together with the cast on stage, through his lights. He has a creative, inquisitive approach to the story line and music. He asks questions about the story, alongside technical and cue questions, and co-creates with us the best ways to bring that story across. He made use of the musical score of IT to understand the music and find the tension line and cues he needed to create the right atmosphere. He always hummed and tapped along with us to make sure he was following and connected to what was happening on stage.

Teus was faced with a number of challenges, such as the different heights of the venues and their technical abilities, as the Muziekzomer often presents at unconventional venues, which do not always include conventional technical requirements. A number of scenes always had to be checked and eventually readjusted before a performance because of those variable parameters. (This topic is developed further in Chapter IV. “Premiere and Touring”)

Sound design: Maurits Thiel was our sound designer and once again, the reason why he is a designer is because he commands the speakers in a manner similar to playing an instrument. He did wonders with the sound, despite the conditions we presented him with. He was faced with rather challenging and drastic situations that needed solving, starting with the usual adjustment to the sound qualities of various venues, all the way to making use of creative means to solve unconventional challenges. Maurits accommodated any wish we had and thought along with us what the best choices were.

Maurits was very helpful in balancing the sound of the tapes that Brito had created and match extremely well the atmosphere they were creating with the acoustic instruments input/our voices. I believe he played around with the brightness/darkness, volume and reverb, alongside dozens more options for the sound quality at all times.

A crucial moment was the destruction of the drum set. Great idea but then, there can, by any means, be no microphones on or around the drums. No budget is ever going to cover that for four shows (what is left for a tour). What he came up with is extremely clever.