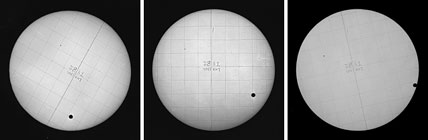

This is a story of another use of glass plates: 1882, astronomer David Peck Todd traveled to the Lick Observatory in California to photograph Venus transiting the face of the Sun from their solar photographic telescope. More than a century later, these frames were digitalized, animated, and compiled into a movie. As the transit unfolded, Todd obtained a superb series of plates under perfect skies. His 147 glass negatives were carefully stored in the mountain vault. But as astronomers turned to other techniques for determining the scale of the solar system, the plates lay untouched and were eventually forgotten. 2002, Anthony Misch and Bill Sheehan found all 147 negatives, still in good condition, at the observatory. To their knowledge, this collection of photos constitutes the most complete surviving record of a historical transit of Venus. As they looked at Todd's extensive sequence of images, they realized they could turn them into a film. A similar thought may have occurred to Todd himself, for a number of his contemporaries were already making the first forays into chronophotography — the forerunner of cinematography. Indeed, Pierre Jules Janssen invented his famous photographic revolver to capture the 1874 transit of Venus. It was actually this instrument that originated chronophotography, a branch of photography based on capturing movement from a sequence of images. To create the apparatus Pierre Janssen was inspired by the revolving cylinder of Samuel Colt's revolver.

The revolver used two discs and a sensitive plate, the first with twelve holes (shutter) and the second with only one, on the plate. The first one would take a full turn every eighteen seconds, so that each time a shutter window passed in front of the window of the second (fixed) disk, the sensitive plate was discovered in the corresponding portion of its surface, creating an image. In order for the images not to overlap, the sensitive plate rotated with a quarter of the shutter speed. The shutter speed was one and a half seconds. A mirror on the outside of the apparatus reflected the movement of the object towards the lens, that was located in the barrel of this photographic revolver. When the revolver was in operation, it was capable of taking forty-eight images in seventy-two seconds.

At the base of this effort, there was again a scientific challenge: in that period scientists wanted to determine the astronomical unit and be able to measure the Solar System. Only the Venus transit was enabling this procedure.

The technology developing around the chance to capture phenomena connected to darkness and the study of the sky would require a chapter on his own in history of film technology: how and why was there an interest in creating instruments able to mediate information? Initially there were no audience concerns, but the instruments eventually became devices for communication with other recipients than those intended at the start.

Digital imaging technology made reanimating Todd's transit images a comparatively simple undertaking. The result, which premiered at the International Astronomical Union's general assembly in Sydney, July 2003, appears below and shows Venus's silhouette flickering strangely as it marches across the Sun's face. It's the shadow-show of an astronomical event— a moving record of an event seen by no one living now, and a preview of what millions saw once in their lives on June 5–6, 2012.

https://skyandtelescope.org/observing/celestial-objects-to-watch/reanimating-the-1882-transit-of-venus/ © 2003 University of California Observatories / Lick Observatory.