Establishing the Musical Storyworlds

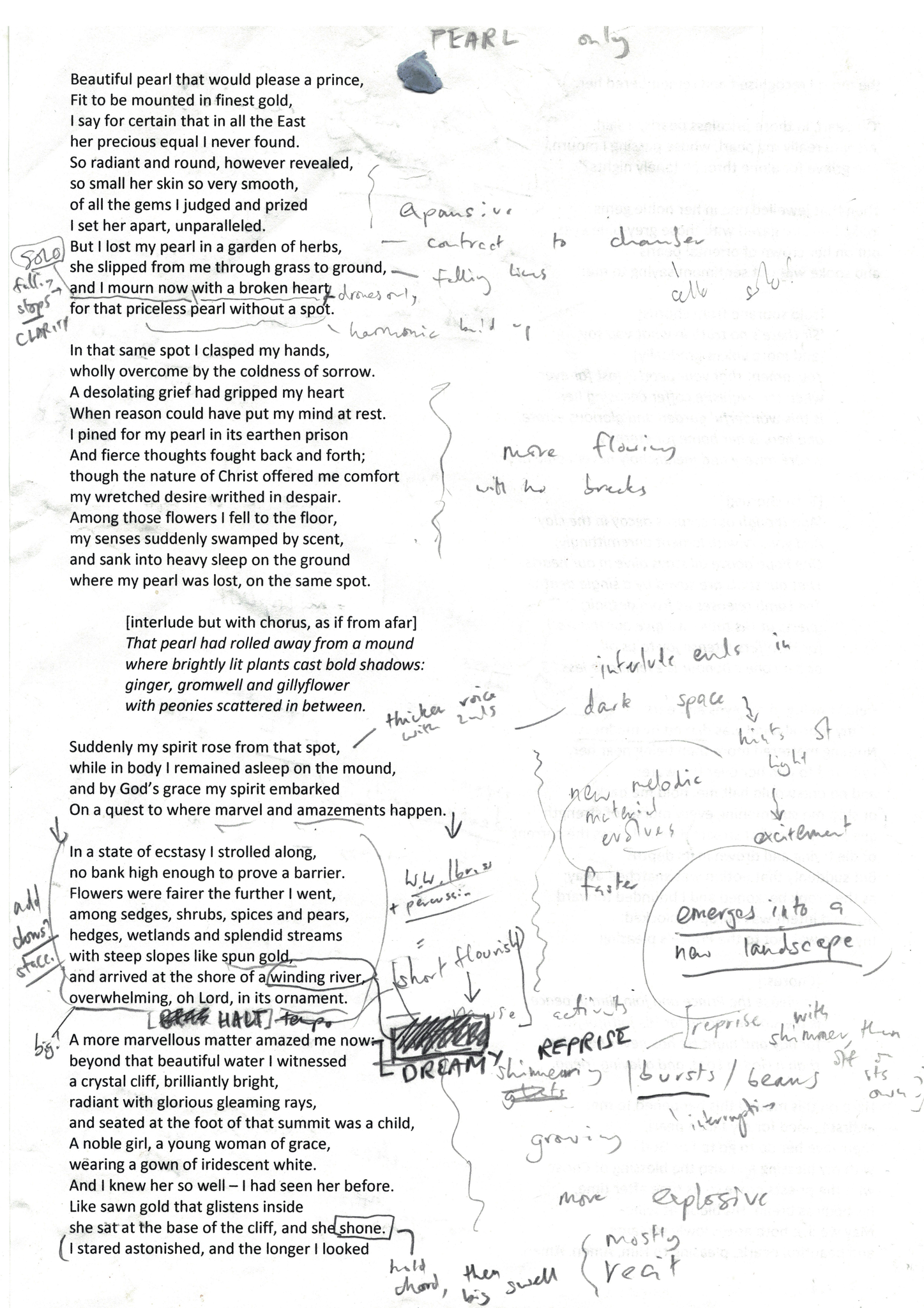

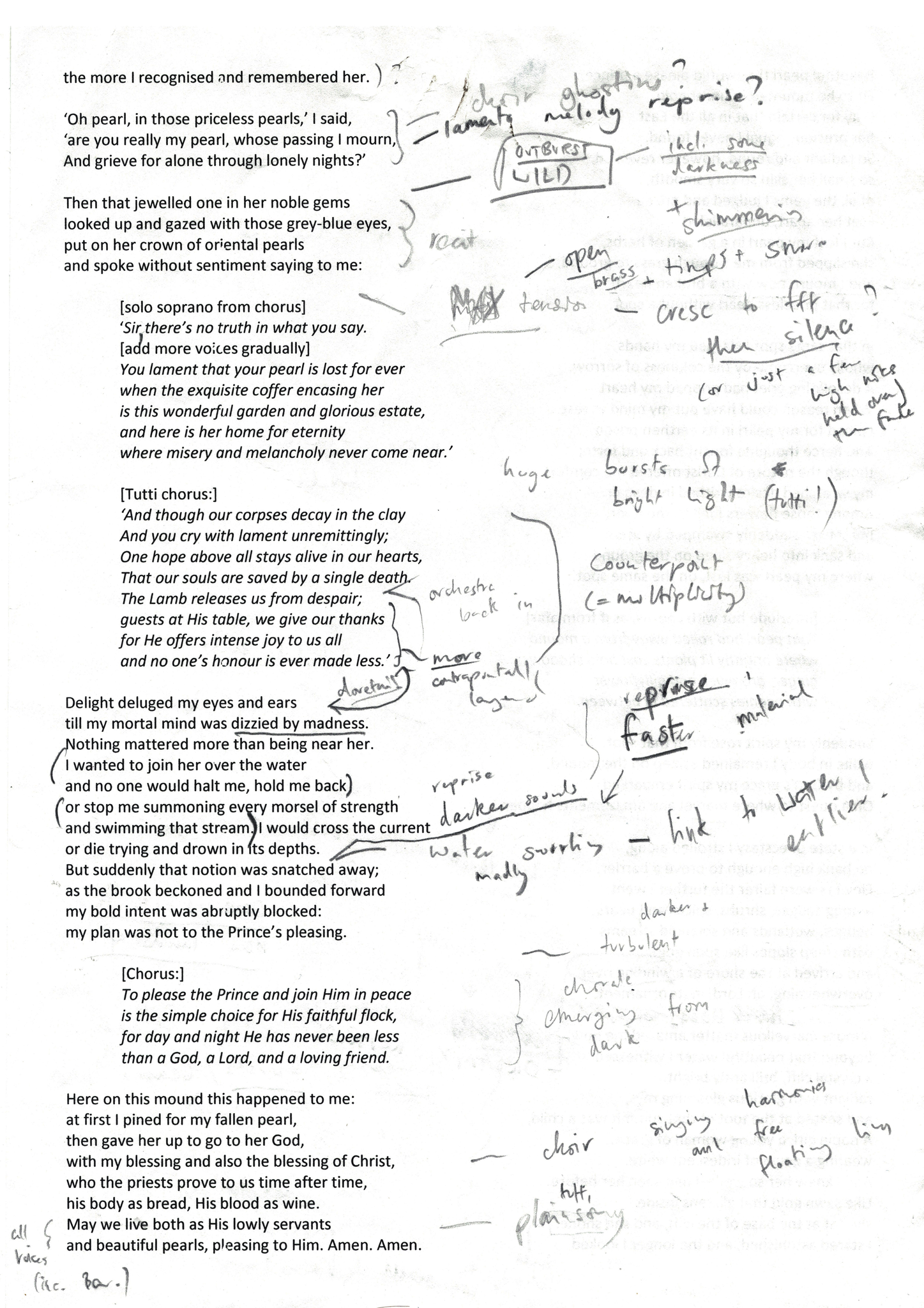

In a recent publication for Adaptation (Kaner 2024), I analyse the first movement of my clarinet quintet, At Night (composed concurrently with Pearl, and thus sharing many of its narratological techniques, including the musical depiction of dreaming), by drawing on the scholarship of transmedia narratologist Marie-Laure Ryan (2014) to demonstrate how a sequence of differing musical storyworlds adapts and depicts the narrative of Robert Louis Stevenson’s poem ‘The Land of Nod’ solely for instrumental forces. To do so, I employ Ryan’s storyworld components (Existents, Setting, Physical Laws, Social Rules and Values, Events, Mental Events) (2014: 31–37) alongside Almén’s (2008) specifically musical narratology as a way to unpack my use of familiar musical topics (see the following section) and their underpinning with evolving harmonic processes, to convey a succession of narrative ‘scenes’ and unfolding ‘events’.1 Thus, as I set about creating the broad narrative-structural outline of Pearl, I took a similar approach to adapting Armitage’s translation of the poem: seeking out appropriately characterful, topical, materials to depict the storyworlds of the piece. This approach can be seen in my early annotations of the libretto (reproduced in Figure 2), which offer both literal musical (‘mostly recit.’/ ‘open brass’) and metaphorical descriptions (‘burst of bright light’) of the emerging musical work, including those that pertain to its long-range harmonic design (‘MAX tension’), demonstrating my early concern with both the storyworlds of the piece and its narratively underpinned harmonic teleology.

Employing Topics to Situate the Musical Narrative2

Leonard Ratner’s Classic Music: Expression Form and Style (1980) introduced topics to the lexicon of musicology as an early eighteenth-century ‘thesaurus of characteristic figures’ with various associations including specific ‘affections’ and ‘picturesque’ qualities, that could be employed by composers as ‘subjects for musical discourse’ (9). In the more recent Oxford Handbook of Topic Theory, Danuta Mirka offers a refined definition, which since Ratner’s seminal work has gradually expanded in meaning through its use in the work of many scholars; her position is simply that topics are ‘musical styles and genres taken out of their proper context and used in another one’ (Mirka 2014).

In a significant sense, then, topics are a specific form of musical intertextuality (‘intermusicality’ as Wolf (2008: 213) terms it). As Mirka notes, they are frequently associated with certain affects (pathetic, tragic), and often in conjunction with certain melodic tropes (such as the sigh motive, Mannheim rocket), in that they ‘allow one to recognize a style or genre [… to] form part of topical signification’ (2014). Such a framing thus positions topics as a ‘source of meaning and expression’ (Mirka 2014) and arguably offers composers of narrative works a valuable tool with which to ‘get us into the musical story’ (Klein 2013: 23).

How exactly topical signification takes place varies (and can be subject to debate). On the one hand, topics may act mimetically, by resembling the sighs, accents, and inflections of the voice, as ‘indices of emotional states’ (Mirka 2014). Yet they may also operate as signs associated with affect by cultural-historical convention, whereby ‘affective signification of topics is indirect because it arises from their similarity (icon) to genres or styles that, in their turn, are associated (index) with specific affects or affective zones’. If the latter is true, ‘recognition of these affects is based on the listener’s recognition of styles or genres’ (Mirka 2014). Nevertheless, music psychologist Patrik Juslin posits that our perception of musical affect may be directly triggered by mimicry (or exaggeration) of ‘voice cues from emotional speech, such as vibrato, sights, screams, moans, or a ‘crying’ voice […] which leads us to ‘mirror’ the perceived emotion internally’ (2019: 291), and Mirka herself concedes that listeners can perceive a topic’s affect ‘by virtue of musical motion characteristic of it’ (2014), even when it is unfamiliar to them. Ratner’s original definition also includes ‘picturesque’ effects that more directly imitate of external (non-vocal) sounds. Again, while the use of pictorial effects need not imply reference to other music, certain well established topics have been shown to ‘originate in pictorial effects that have turned into styles’, meaning that their signification ‘arises from their similarity to genres or styles rather than from direct musical imitation of nonmusical sounds’ (Mirka 2014).

This emphasis on intermusical connections similarly informed my thinking around topics in Pearl, which form a broad network of significations (including the picturesque and emotive), with a range of origins, and in all cases, in relation to other musical works of some kind. Whether or not listeners are immediately aware of these was of less concern to me; as Umberto Eco notes regarding literary intertextuality, the device often ‘provokes in the addressee a sort of intense emotion accompanied by the vague feeling of a déjà vu’, acknowledging that no ‘intertextual archetype is necessarily “universal”’ (1985: 5, my emphasis), and is contingent on the cultural knowledge and experience of the reader (see also Primier 2013: 93).

Nevertheless, through my most recent series of projects, I have come to see topics a powerful musical storytelling technique that can furnish listeners with interpretational cues with the power to enrich their ‘understanding of the way music carries particular meanings’ (Almén 2008: 92; cf. also Kaner 2024). As Almén emphasizes, the presence of topic(s) never necessarily denotes the presence of narrative and vice versa, explaining that ‘topic is expressively static’, whereas ‘narrative is expressively dynamic’ (Almén 2008: 48). Accordingly, I consider it incumbent on me, as a composer drawing on the semiotic potential of topics in the service of musical storytelling, to do so with an inherent musical dynamism that facilitates the evolution of hierarchies over time (as is crucial to Almén’s conception of narrative). This process can involve the juxtaposition of contrasting topics through the course of the work (‘troping of two otherwise incompatible styles [… to] create new meanings’) (Hatten 2004: 68). However, it is equally possible for narrativity to arise within a single topic (‘topic as frame’) (Almén 2008: 79), through the manipulation of parameters such as harmonization, rhythm, texture, all of which may signify changing affective states and interrelations between the constituents of a narrative musical hierarchy. Both strategies were important for me as I composed Pearl, as I discuss below.