Politics of collective movements in post-socialisms

Volha Sasnouskaya

The research addresses collective movements and their exhaustion (bodily and political), focusing on choreographies of protest actions, socialist mass celebrations and raves, and the relation between festive and the political. It approaches collective choreographies through the concept of a movement score, used in dance studies to graphically record, analyse, preserve and transmit dance and movement. In this research project a movement score is seen as any kind of graphic transcript of movement (including text) that intersects multiple temporalities of its enactment, and is used as a tool to critically approach the temporality of political action and to question the linear time of revolutionary event.

The project departs from archival materials on the socialist mass celebration published in the USSR and available at the National Library of Belarus, and from the experience of 2020-21 anti-governmental uprising in Belarus against the rigged elections, and its consequent suppression, followed by the ongoing Russia's invasion in Ukraine, supported by Belarusian government by the use of its territory and infrastructures. It analyses specific collective choreographies (state parades, protest marches and gatherings, raves, various acts of disruptions and sabotage) and traces the transformations of the notion of political movement in post-socialisms.

In socialism, state ideology was represented and rehearsed though the bodies and collectives movements — in mass revolutionary spectacles but also in everyday practices (for example, physical culture). Ana Vujanovic (2013) suggests approaching them through the notion of social choreography developed by Andrew Hewitt (2005). The shifts in this performance of state ideology in late socialism could be described as the condition of “vnyenahodimost” (being outside, spaces of out) (Yurchak 2005), when still participating in official rituals, people would give them new, unexpected meanings, being at the same time within and outside the existing power discourse.

I would claim that after the fall of state socialism, neoliberal transformations and instalment of authoritarian political regimes in the region, the notions of the collective and of political agency in Belarus, and in most of post-soviet region, has been in crisis.

Being normally crucial for the social unrest, collective movement had a particular place during the 2020-21 uprising in Belarus important specificities. In Belarus, the public space is severely restricted, with very strict laws on organisation of protests and regular practice of their suppression. So general political participation has been often implemented though non-direct political activity, such as civic organisations or culture. At the same time the state still stages military and physical culture parades, however much less spectacular and met with almost no enthusiasm. In the 2020-21 uprising, with a state monopoly on legislation and public speech, direct bodily engagement remained the only and most efficient means of struggle, whose affect also guided political imaginations regarding the strategies and prospects of resistance.

The most common protest choreographies were procession — protest marches, walks or solidarity chains, and various forms of disruption or refusal — strikes, labor unrest, withdrawals, walkouts, etc. I would claim that two essential characteristics of those choreographies — exhaustion and interruption — are crucial for understanding the dynamics and potentialities of the uprising. As the provide a different perspective on political action and temporality, where not only political movement, but also the stuttering, the interruption of linearity of revolutionary time, which is often imagined as driving either to a definite failure of victory, becomes a political practice (Sosnovskaya 2021).

How the exhaustion and disassembly of socialist choreographies, and this overlapping of crises of collectivity and political agency shift the notion of politics in post-socialism? Whether there are new forms of collective choreographies that enact political agency, and in what way?

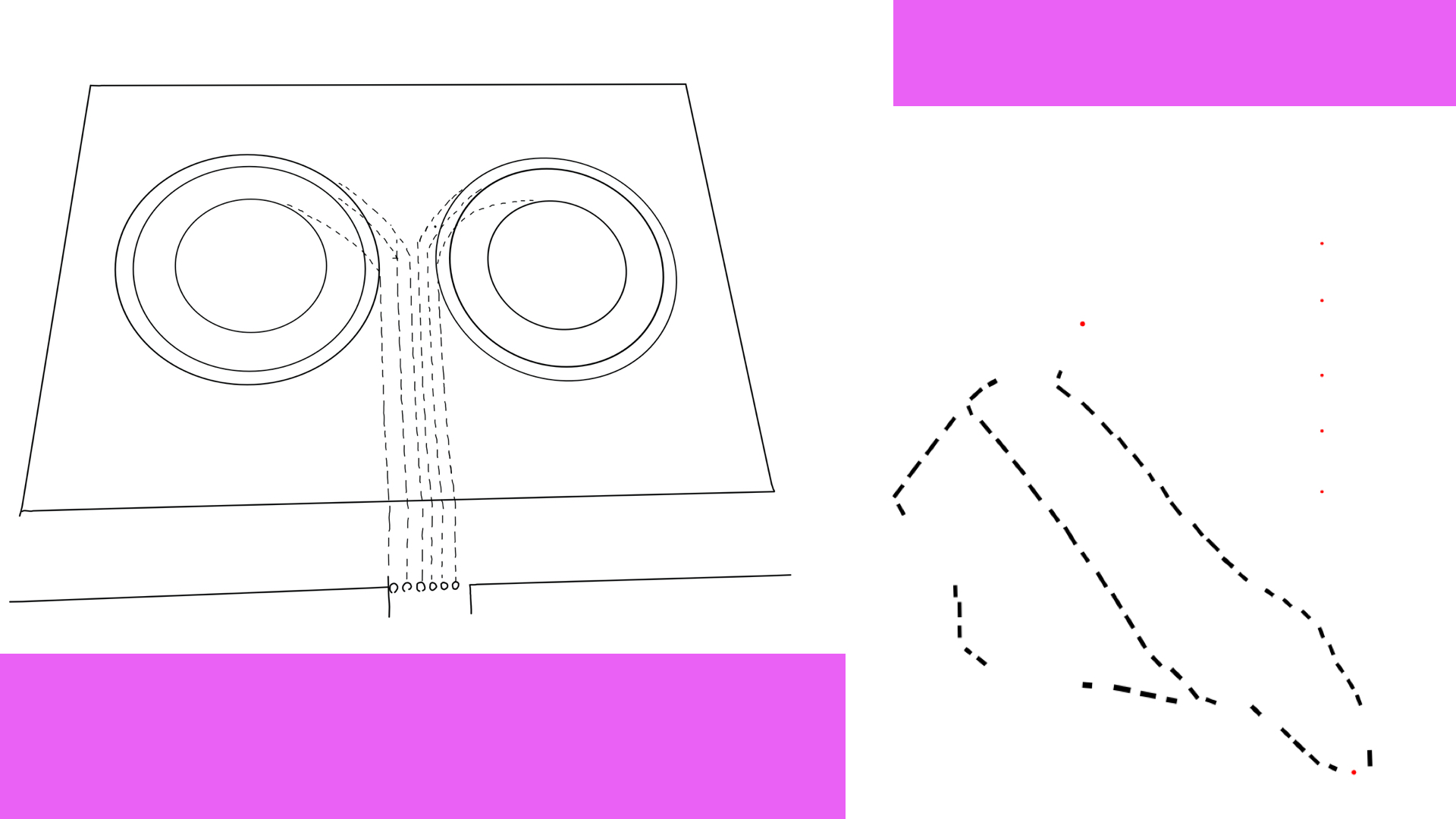

In dance studies, a movement notation is a tool to graphically record, analyse, preserve and transmit dance and movement; the movement score brought a new approach, implying less stability, multiple possibilities, uncertainty, stressing the process of interpretation (D’Amato 2015). In this research the notion of score brings together texts and movement notations for the soviet revolutionary mass celebration from the National Library of Belarus, and routes of the protest marches during 2020-21 anti-governmental uprising in Belarus, each being characterised by certain kind of exhaustion (political and physical).

The project inquires how movement score of mass choreographies and protest marches adds to the understanding of political movement and political event.

As a conceptual or methodological tool movement score is crucial from several points — it’s relation to body or bodies and time.

Reading and writing a notation score is “the essentially somatic experience”, requiring reader/performer active physical participation (D’Amato 2015, 2). Since the score is always shared — by multiple of bodies that performed and read it — it troubles the notion of authorship (Gies 2010). Score is thus not a complete explanatory tool, but also a tool to stress what stays beyond the archive, what is forgotten, omitted, non-articulated, remains in the body and is not meant to be shared. Always incomplete and unstable, the score is not so much a representation of movement, but rather an outline of possibilities (Watts 2010). Movement score also stresses the complex relation with time, history, and the body. It connects the past, documenting the notated movement, with the present moment of its reading and embodiment, with its potential future enactments. “Because a score potentially contains various and different possible futures, it is always political” (Gies 2010, 83). Working with the socialist choreographies adds another layer, since in socialism, the future and its collective imagination in the experience of celebration and revolution, connected to the “festive energy” and emotions was part of political project, an act of creating visions of a future and its realisation (Mazaev 1978, 223), that is now being looked back at though the archive. At the same time, reading closely the materials on mass celebrations, one notes that many of them bear a more complex temporality. The time of the event is blurred: it involves revolutionary histories one is going to celebrate — or even stages it — and the program for the future. At the same time, later socialist texts are characterised by certain a-temporality: published shortly before the collapse of the USSR, they were written in the very similar language of the more early texts, as if denying the passage of time since the October revolution. Thus the materials on mass celebrations bear a complex temporality, intertwining rehearsal, repetition and political action.

Another troubled temporality is the notion of post-socialism, which is often criticised for unifying various geographies and historical experiences of different former socialist territories. It is also criticised for being always characterised by its absent past — socialism, thus being just a disguise of the future promised by the neoliberalism, a never-ending catch-up to Western colonial temporality. A future which states the impossibility of any alternative futures, of any alternative to capitalism (Müller 2019).

Speaking from the present moment of crisis and political ruin (of post-socialism, of smashed revolution in Belarus and the ongoing war in Ukraine), I am questioning the notion of ‘aftermath’ and employing the concept of repetition (of movements, texts and historical events) or rehearsal embedded in the movement score to simultaneously address the past and future of the collective movement.

Writing about the experience of the smashed Grenada Revolution, David Scott addresses the “contemporary aporia of the crisis of political time” (2014,). He claims that whereas modern historical time has been normally understood as a linear continuous change, leading to some improvement, now these rhythms of relation between past, present, and future have been broken or interrupted: “And what we are left with are aftermaths [of political catastrophe], in which the present seems stricken with immobility and pain and ruin; a certain experience of temporal afterness prevails in which the trace of futures past hangs like the remnant of a voile curtain over what feels uncannily like an endlessly extending present”(2014, 6). He however states that these catastrophic aftermaths have provoked “a more acute awareness of time, a more arresting attunement to the uneven topos of temporality” (2014, 2). I wonder if this interrupted linearity of revolutionary time have also a different potential, could it be that a stretched-out present opens a space of possibility?

The present seen as a a profound and lasting temporal break, for rehearsing and exercising the future now, “… an event of … enduring unfolding of affective connections, an ‘affect virus’ through which new socialites emerge” as Isabell Lorey puts it (2019, 38).

Then there is also a possibility to rethink post-socialism not as afterness or belatedness, but, as Neda Atanasoski and Kalindi Vora approach it, through the notion of queer time, which “complements the past conditional temporality of what could have been,” as non-unified, and propelled by multiple political desires and uncertainties (2018).

This project approaches movement score as any kind of graphic transcript of movement (including text) that intersects multiple temporalities of its enactment. Further developing the definitions of a score departing from the research materials, it could be added that:

Score is a guideline one would not trust or maybe even rebel against.

It departs from certain political event or experience and triggers political action for the future; The present time is the most uncertain.

Score might be strict but the command loses its power as soon as it is pronounced or read.

It demands political engagement, but it might be different from what is inscribed in the score.

Making a score means being engaged in a shared political practice, in the event that started before you and will continue with or without you; a collective movement, that could be fulfilled and enacted anywhere, at the distance. You might even not want to be part of it and deny your relationship, but score will incorporate your movement without your willingness. In that sense it is always collective.

By enacting a score, the energy, the conditions, certain powers of the original event are re-enacted. This repetition establishes a new temporality, which is fragile. And is meant to be exhausted. The action continues after the exhaustion.

Score is mundane.

What does it mean to treat historical document and event as a score? Does it acknowledge both the untranslatability — of the political event, bodily movement and affect — and the possibility to be activated and shared? Could the document or even the political event it refers to be transformed and unsettled through the act of it reading? Does it allow us to establish a different, corporeal relation to the archive and past events? Does it allow to establish a more complex temporal relations between the political events, archives and projects, other than linear logics of genealogy, as in socialism transitioning to post-socialism? What stays in the body after the event, after the experience of revolution — and how the movement could be continued? What if revolutionary movement is a set of unspectacular intimate gestures?

The exhausted movement continues in a score, always ready to be activated, precisely making the breaks, interruption and exhaustion significant, and unsettling the relationship between past and future, event and a document.

The artistic method to approach those movement scores and research materials imply a series of operations that intertwine movement, texts and visual representations, such as lecture-performances and collages.

Lecture-performance texts are composed through a montage and quoting of various historical and theoretical texts and images. Their recomposition suggests other modes of reading, narrating and interpreting, articulating the overlaps, exhaustion, ruptures and stumbling, playing with discursive power and triggering new, unintended meanings, affects and fantasies to emerge. They often imply choreographic gestures of embodying the scores, experimenting with the modes of reading, rhythm, scale and duration; with exhaustion of choreographies through repetition. Through those artistic practices I wonder what stays in the body after the event, after the experience of revolution — and how the movement could be continued? What if revolutionary movement is actually a set of unspectacular intimate gestures?

References

Atanasoski, Neda, and Vora, Kalindi. 2018. “Postsocialist politics and the ends of revolution”, Social Identities no. 24 (2): 139-154.

D’Amato, Alison. 2015. Mobilizing the Score: Generative Choreographic Structures, 1960-Present [Doctoral dissertation, UCLA].

Gies, Frederic. 2010. “Score Politics” In Alice Chauchat (ed.) Everybodys Performance Scores. Everybodys publications: 82-83.

Hewitt, Andrew. 2005. Social Choreography: Ideology as Performance in Dance and Everyday Movement. Durham: Duke University Press.

Lorey, Isabell. 2019. “The power of the presentist-performative: on current democracy movements” In Ana Vujanovic and Livia Piazza (eds.) A Live Gathering: Performance and politics in contemporary Europe. Berlin: b_books.

Mazaev, Anatoly. 1978. Prazdnik kak social’no-hudozhestvennoe iavlenie: opyt istoriko-teoreticheskogo issledovaniia [Festival as a social and artistic phenomenon: a case of the historical and theoretical study]. Moscow: Nauka.

Müller, Martin. 2019. “Goodbye, Postsocialism!”, Europe-Asia Studies, no. 71 (4): 533-550.

Scott, David. 2014. Omens of adversity: Tragedy, memory, justice. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Sosnovskaya, Olia. 2021. “The Walk. On gestures, movements, and rhythms of the current resistance in Belarus” In Kasia Wolinska (ed.) Danceolitics. Berlin: Uferstudios GmbH.

Vujanovic, Ana. 2013. “The “Black Wave” in the Yugoslav Slet: The 1987 and 1988 Day of Youth”, TkH (Walking Theory), no. 21 (Social Choreography): 21-28.

Watts, Victoria. 2010. “Dancing the Score: Dance Notation and Différence”, Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research, vol. 28, no. 1: 7-18.

Yurchak, Alexei. 2005. Everything was forever, until it was no more. The last Soviet generation. Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Citing Sources

performance

2021

I am looking at the text, opened in front of me. l Reading is a gesture. l I trace the geometry of its lines, trying to slip off to the margins. l In the stillness of a page, I am trying to imagine the preceding and the forthcoming move. [slide]

The piece derives from artist's reflections on the materials she encountered in the National Library of Belarus, while studying the concept of a socialist celebration: books, texts, images. This story overlaps with her experience of the recent and ongoing anti-government protests in Belarus. The performance traces the relationship between the language and movement, event and document, affect, score and the political. Understanding score rather broadly, as any graphical or textual material describing and calling to action. It operates on multiple temporalities: the past of a movement’s trace, the future of the constantly imagined action, the present gesture of a reader.

Production Centrale Fies_art work space (IT) / Live Works

With the support and choreographic advice of Alix Eynaudi and Elizabeth Ward; and Aleksei Borisionok

Supported by Huggy Bears Art Space and Tanzquartier Wien

Documentation:

'A Forest Marathon. pARTisanka Party’ / HAU (Berlin, Germany) 2022.

‘Performing Infrastructures’ / ZIRKA (Munich, Germany) 2022. Photo credit: Constanza Meléndez

LIVE WORKS SUMMIT / Centrale Fies (Dro, Italy) 2021. Photo credit: Roberta Segata, Courtesy of Centrale Fies

Exercise

digital collage, digital print on textile

2021

The work explores relationship between language, affect and political movements through the concept of “scores” in the context of the ongoing uprising in Belarus, as well as other political events in (post)socialist history. Analyzing movements as gestures and collective choreography, the artist uses the concept of scores in a broader context: as a graphic record of motion, including texts, documents, images. The score is used in recording movement, dance or music, and allows to operate in multiple temporalities.

A as a means of representation, it suggests a certain degree of untranslatability. The artist studies the use of language, speech and text in politics, in describing current events and experiences of the past. She addresses affects of language and explores what remains beyond language.

Incredibly relaxing meditation music

lecture-performance

series of prints on textile, 40x40cm

2019

Intertwining multiple voices and visual quotes with a stuttering music mix, the work studies the concept of exhaustion. The artist’s narration fluctuates between body energies, dynamics of the affect, contemporary capitalist impositions, historical politicality of stillness, choreographies of the imagination, the multitude of the undoing, etc. etc. etc.

Exhibition view:

'ODKSZTAŁCENIE / ДЭФАРМАЦЫЯ / UNLEARNING' group show / Domie (Poznań, Poland) 2021

'Turn up, time of my life, go up in fire', group show / Display (Prague, Czechia) 2023

Text

text, digital collage

2020

A letter about the impossible experience and about the invisible strike of library workers; a manifesto of striking readers. Minsk 2019, 2020, and 1973*.

Exhibition view:

'A Secret Museum of the Workers Movement', group show / Hoast (Vienna) 2021. Photo Credit: Wolfgang Obermair

'Outdoors, gunpowder burns quietly'

solo show

Annenstrasse 53 (Graz, Austria)

2023

The title of this installation cites a soviet book on pyrotechnics and mass celebrations, which played an important part in socialist political imaginaries. The works installed at Annenstrasse 53, are imbricated in Sosnovskaya’s ongoing research, which investigates the collective movements, protest choreographies, and politics of celebration. The works depart from the texts describing and archival materials from official socialist festivities, as well as Sosnovkaya’s personal experience of the recent political movements and raving during the time of post-socialism. Where rhymes, failures are revealed in the collision of different images and narratives through montage and quotation, special effects of powerpoint aesthetics are superimposed onto the affects of language and its insufficiency, tracing the multiple temporalities of political action.

“Exercise” (digital collage, print on textile, 2021) explores relationship between language, affect and political movements through the concept of “movement scores” in the context of the 2020-21 anti-governmental uprising in Belarus, and other political events in post-socialist history. It approaches the post-socialist temporality critically, through a complex non-unified experience of various desires, actions, imaginations, and potentialities. “Outdoors, gunpowder burns quietly. In a closed space gunpowder explodes” (digital collage, print on metal, 2016) refers to the idea that fireworks and gunpowder used in the military are parts of the same power and ideological constellations. “The F-Word” (video, 12:10, 2021; in collaboration with a.z.h.) addresses political struggle, police and state violence through the discourse of fascism during 2020-21 anti-governmental uprising in Belarus, tracing the political, social, affective and symbolic effects it produced. The video is part of the “Armed and Dangerous” project and platform initiated by Mykola Ridnyi (Ukraine).

After the brutal suppression of the 2020-21 uprising through continuous repressions and with Russia’s support of the regime, Belarusian territory and infrastructures are now being used for Russia's war on Ukraine, what raises new urgent questions on the collective agency and strategies of political action.

Photo Credit: Simon Oberhofer

'Reading is a gesture'

workshop at TQW Winter School / Tanzquartier Wien (Vienna, Austria) 2023

workshop within the program “Collective Art Practices: Reimagining the Future” / Bult night club (Almaty, Kazakhstan) 2023

'Exhaustion is a practice' workshop at 'To Get Things Done: Energy Politics and Aesthetics' / Josefov Summer School (Jaroměř, Czechia) 2023

The series of workshops address the notion of political movement and its exhaustion, exploring the bodily relation to political events and festivities.

It engages with texts, documents and personal experiences focusing on protest gestures and choreographies through collective writing, reading, and movement practice. Shifting between mass gatherings and intimate gestures, uprisings and celebrations, bodily movement and its interruption, the workshop invites us to approach historical documents and events through a notion of movement score, questioning the definitions of the political and unsettling the linear temporality of the revolutionary event(s).

Related publications:

Olia Sosnovskaya. Future Perfect Continuous / Ding magazine #3 'About the future in times of crises'. 2020

Olia Sosnovskaya and Aleksei Borisionok. 'The Futures of the East' In Baltic Triennial 14: The Endless Frontier (A Reader), edited by Valentinas Klimašauskas and João Laia, Contemporary Art Centre (CAC), Vilnius and Mousse Publishing, Milano. 2022

Olia Sosnovskaya. 'The Walk. On gestures, movements, and rhythms of the current resistance in Belarus' In Danceolitics, edited by Kasia Wolinska, Uferstudios GmbH, Berlin, Germany. 2021

Olia Sosnovskaya. 'Shouldn’t language go on strike too?' / TQW Magazin. 2021

Olia Sosnovskaya. 'Incredibly relaxing meditation music', Score for a performance lecture (fragment) In Artistic practice and social change. Observations from from Belarus and Sweden. Konstepidemin Publishing House, Gothenburg, Sweden. 2019

Olia Sosnovskaya. 'burn, on fire, alight, inflamed, glow, ablaze, fervent, go up in smoke,' Score for a performance lecture / Anrikningsverket Journal №1: Convulsion. 2019