According to a recent ancestry DNA test conducted by i3S (Institute of Investigation and Innovation in Health, Porto University), my genetic GPS is Germany, even though I, and my family for as long as I have known, are British. That said, I have lived and worked outside the UK since 1998. The point is, however, that while distances across time can be geographical, inasmuch as humans are involved one can add to this such distances’ subjective effect. By subjective, I myself am placed as a sentient being amidst my physical actions and movements, and in part such sentience impacts on and determine the latter. Keeping with this idea of genetic ancestry, only 0.5 % of me is Neanderthal, a species which is considered to have become extinct some 30,000 years ago, but not before interbreeding with Homo sapiens who first left Africa at some 65,000 years (New Scientist, 2021, p.101). Spatial and temporal distance is involved in this mapping to a complex extent, considered through a lens – writing and visual artwork – that distances me from what is otherwise self-reference not so much by the content but by the two combined mediums. Yet this question of distance is paradoxical, since the medium is at-once a separator and a binder.

Insofar as distance can concern one’s own intrinsic sense of subject within the work, Ricoeur (1992) suggests that ‘selfhood implies otherness to such an intimate degree that one cannot be thought of without the other; that instead one passes into the other…’ (p.3), and proposes a movement between the two notions, personal and public, in the form of ‘narrative identity’ (pp.118-9). ‘Narrative identity’ is the volatile component, as it were; a speculative idea that defuses the question of self with a more mobile notion that can key into and out of overly self-identification. Narrative can as well be constructed, as if one were the chief fictitious protagonist of one’s own novel. Further to this idea of the compound sense of self and other, Ricoeur (2008) terms the ‘dialectical counterpart to the notion of belonging’ ‘distanciation’ (p.32). This has implications concerning the text and, by implication, other creative mediums. Ricoeur states:

…to understand is to understand oneself in front of the text…. …of exposing ourselves to the text and receiving from it an enlarged self, which would be the proposed existence corresponding in the most suitable way to the world proposed’. (2008, p.84)

The efficacy of the Ricoeur reference is due to its concern with the phenomenology of the text (hermeneutics), when text figures substantially in the DNA ancestry project and in my artistic practice in general, and of course as this article itself.

The ancestral DNA reading – any such reading applied to anyone of us – in a sense performs ‘distanciation’. Here one is, determined through biological evidence, yet simultaneously alienated by inhuman statistics and, in my case, a geographically distant genetic GPS. While one may naturally be curious as to one’s ancient origins and lineage through the millennia, forms of art-working make it possible to displace oneself into, arguably, a more engaging example of ‘distanciation’ and so distance oneself from bio-technologically derived content. The following discussion concerns the implications of distance in the research question through more intimate sense of involvement in and as the medium of its exploration.

For the past two years I have maintained an email exchange with the Vienna-based British artist and academic Derek Pigrum. Throughout this correspondence we have shared and tested explanations of theoretical interests in a format that may be termed remote – however well our friendship has developed through this means – and is in this sense distanced. While such an exchange is not, therefore, indicative of ‘distanciation’, occasionally the shared writing is inflective of the Ricoeur definition cited above.

An example of such correspondence may be that while writing this article Pigrum sent me an email conveying two not unrelated references. The first of the references is in response to a comment of mine in my prior email to Pigrum concerning the tiny Oa in Golding’s story, which belongs to a Neanderthal girl called Liku and, when she lays this ambiguous phenomenon down on the ground of a cave, gives it the feminine pronoun. Pigrum (personal communication, August 6, 2023) states: ‘The thing the little girl named female and the fact of the passing down only through the female line [reference to my mention of the female mitochondrial DNA( mtDNA)] suggest to me the very last lines of Goethe’s Faust where he mentions ‘the Mothers’ or the place we all return to until it is time for us to pass into another body. The second of Pigrum’s references is actually a quote by Walter Benjamin from Blanqui in his (Benjamin’s) Arcades project, where in the context of the concept of eternal return, and the repetition in nature of a limited number of ‘heavenly bodies’, Pigrum (personal communication, 6 August, 2023, citing Benjamin), conveys Benjamin’s Blanqui quote to me:

“So each heavenly body whatever it might be exists in infinite number in time and space, not only in one of its aspects but as it is at each second of its existence, from birth to death… The earth is one of these heavenly bodies. Every human being is thus eternal at every second of his or her existence”.

My reply to Pigrum (personal communication, August 7, 2023):

On both counts, I like the idea of the dynamic point; that eternal return has somehow to do with this point of eternal fixation…. I’m relating this idea of point to how the shaft of light, like a spine, meets also at the coccyx of the spine that’s now in my drawing. But it does also credit my intention to stay with the genetic GPS and its centring on Germany….

Such exchange has prompted me to consider that the suggestion of eternity in a point, formally, conceptually, symbolically, may also imply infinite spreading outwards; that eternity has and is an aura. In Golding’s The Inheritors, there are at least two references supporting this idea. (Golding, 2021, p.105): ‘And because he was one of the people, tied to them with a thousand invisible strings, his fear was for the people’. While the idea of ‘a thousand invisible strings’ here concerns place and time, the connection’s invisibility suggests another more cosmic force at work. Golding also writes:

There were the smells of many men and women and children and, finally, most obscurely but none the less powerfully, there was the smell compounded of many that had sunk beneath the threshold of separate identification into the smell of extreme age. (2021, p.190)

The idea of the compounding of smell into that of ‘extreme age’ suggests the at-once bringing together of many bodies, the millennia back in time of the referenced people, and the idea of the infinitude of human life as a concept. However, Lok represents such sheer expansiveness as a corporeal and symbolic point, to which the Blanqui quote also alludes, if one rationalises it as slightly more earthbound than celestial.

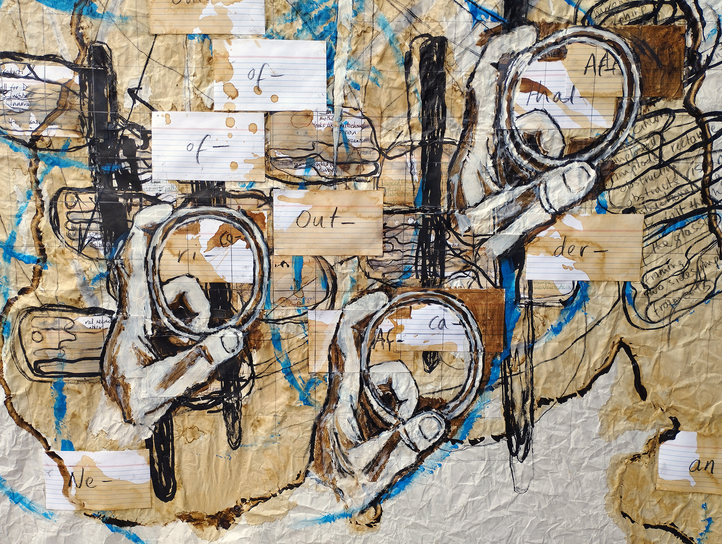

The map of Germany as visible in the two versions in the drawing in the state shown in Figure 6 is in plan view and perspectival elevation, the genetic GPS in the latter pointed to by the vertical shaft of light of the curtains and the coccyx of the spine, both of which are implied in the horizontal undulation of light above the curtains. Ettinger’s theory of the Matrix and Metramorphosis not so much contradict but range contiguously with the predominant psychoanalytical theory of Freud and Lacan. While Lacanian theory points to, and has as its point as the symbolic Phallus and the symbolic Father, Ettinger’s matrixial is first experienced by the pre-natal embryo in the third term of a pregnancy as the simultaneous within and without of the mother, of the earliest and primitive beginnings of an at-once ‘I’ and ‘non-I’ (Ettinger, 2020, p.126). The matrixial is from then on expansive in an, albeit limited sense, connecting oneself to significant others into the post-natal and onwards through adulthood. Ettinger, however, equates this matrixial movement not to the pre-linguistic Imaginary of Lacan’s three structural psychic registers, Imaginary, Symbolic, Real, but to a pre-linguistic Symbolic, during a time before gender differentiation and subject to a continuity of experience through adulthood as identification with the feminine of the mother, no matter what one’s gender.

I am applying this idea of psychological terrain, as it were, to that of mtDNA; female DNA that is passed only from woman to daughter, beginning with the earliest recorded hominin fossil in Africa some 3.2 million years ago, a girl who came to be called Lucy (New Scientist, 2022, pp.31-2). While ancestral DNA is a topic of significance to the entire globe and many millennia of time and space, where the female gene, as opposed to the male Y chromosome, provides biologists the greater evidence – which is itself a global matrix – Ettinger’s matrixial is significant just in the present psychic life of an individual and in relation to the others within one’s immediate community. However, given that I invest a sense of self in my visual practice anyway, in this instance through a few prompts from the ancestral DNA test, the smaller matrix extends via the human subject – in this case the internal-me in relation to a movement towards externalisation of an idea – and the far larger matrix contracts according to my focus on but a modicum of its potential for exploration.

In the context of discussion of the difference between the Latin route of the term God and the Hebrew equivalent, AHIH, Ettinger (2020) equates the former with the question of ‘being’ only, and the latter with an understanding of being that also encompasses ‘becoming’ (pp.136-7). This is interesting in relation to Pigrum’s reference (cited above) to Blanqui’s understanding of human’s eternality that can have as its metaphor the point, which can therefore also accommodate the idea of becoming, a future time, and physical movement. Further in the same context, Ettinger (2020), through the metaphor of ‘migration’, has referred to three kinds of exile: ‘…“inverted exiles” a migration to an unknown desired destination’; ‘…“return” for migrations towards a known destination’; ‘…“exile” for movements of expulsion… abandonment of the desired place…’ (p.135). Across time, place, and space, one can imagine that mothers and daughters will have been variously subject to all three types of migration in their lineage down to oneself in the here-and-now, albeit for one’s brief time on earth.

While the text that constitutes the present article is of course itself open to hermeneutical analysis, a more apparent example for such consideration would be either transcription of speech – such as the short instance above – and the relatively more enunciated language of emails, however academic their content, the latter especially when their addressee is a friend. What follows by way of example, is my email addressed to Pigrum (personal communication, August 13, 2023) that was the first iteration of what I explain, above, of Ettinger’s interpretation of becoming:

I've been encouraged to write this partly through reading… Ettinger on the meaning of the name God in the book of Exodus. Ettinger contrasts the Latin, Greek, French and English meaning of the term AHIH, which is Hebrew for God, as it occurs in Exodus, and means 'I am', with the Hebrew meaning, 'I will be/become', the latter of which infers the idea of future and movement, rather than the static now. Then Ettinger (2020) states: 'AHIH ASHER AHIH [Ettinger translates it as 'I am that I am', or 'I am that is'] is a future departure leading to another future departure with no resting point or destination. It indicates a movement of desire with no objective, no destination. Any fantasy that occupies the place of the object of desire of the first I will be/become, is expelled by the second I will be/become. The repetition itself traces a chain of future distances, and thereby evacuates any fantasy objects'.... Being and becoming, although coinciding in Hebrew, are incompatible in French and English' (pp.136-7). This last sentence seems to in part answer why Lacan critiques philosophy from the point of view of being, since in his theory becoming is by far the more important condition….

The comment I make within the email in its last sentence concerning Lacan’s critique of philosophy has been in mind due to some reading from several months ago. In his Seminar XIX, …or Worse, Lacan (2018) discusses the difference between the One as being and the One of repetition (p.116). According to Badiou (2018) on this question of critique of philosophy, Lacan challenges being as used in the philosophical sense by thinking (p.140). Badiou (2018) states: ‘…in Lacan’s eyes… there is thinking only where there is a local absence of being’ (pp.61-2). This is given that thinking is associated with becoming. I am therefore drawing a link between Ricoeur’s ‘distanciation’, of which the above is an approximate example in textual practice, when movement within the self concerns what he terms, as cited above, ‘narrative identity’, and the philosophical notion of becoming. It is, however, significant for the latter concept and my recourse to theory for what I myself have had to say in the article, that these have mostly been from the domain of theoretical psychoanalysis rather than philosophy. (One’s visual practice considered in its on-going state as process, is automatically more suited to the idea of becoming than being.)