Eiksmarka Omland is a work situated somewhere between a solo violin piece with tape part and a duet for two performers. The work draws on inspiration from other pieces in Christian’s output as well as being influenced by my folk music heritage and by materials that I previously recorded and shared with Christian. It consists of a pre-recorded tape part and a partly improvised live violin part, together structured around a psalm-like melody. In the tape part, the piano and the Indian harmonium, both played by Christian play a significant role. However, in the process of recording the elements of the tape, we experimented with combining different layers of sound on top of the structure of the melody. Thus, often several elements can be heard at the same time: my violin played with a low octave string, Christian’s Indian harmonium, sounds played with percussion mallets inside the piano, or our improvised clusters of chords and noise-like sounds played on the different instruments. ‘Omland’ is the Norwegian word for ‘surrounding country’. In the work, the live violin is surrounded by those materials that we recorded in Eiksmarka Church in June 2023.

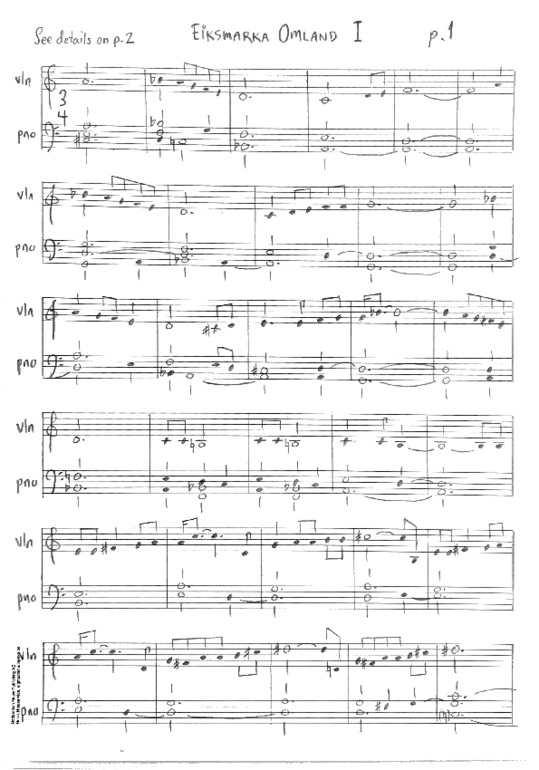

The work is structured in five parts in which parts I, III and V are based on the melody composed by Christian (see score, page 1-2). Sections II and IV act as contrasting interludes and have a more improvised and free character (see score, page 3). When I play with the pre-recorded tape part, I am engaged in a duet with Christian, although in this duet our voices are separated in time. In the concert situation, the tape part is played from an old-fashioned cassette player. This is an attempt to de-technologize the work and a way of representing the absent duo partner with an object onstage next to me. As I will elaborate on below, this way of structuring the live performance in relation to the pre-recorded materials was a topic for discussion and experimentation throughout the compositional work.

The imaginative and compositional work on Eiksmarka Omland spanned five years, from 2020 to 2024. But despite the generous overall time frame from initial workshop to premiere, our work together was affected by the limited opportunities to physically meet. The pandemic struck in the early phase of working together. Sweden, where I live, and Norway, where Christian lives, implemented very different approaches to handling the spread of infection, and this meant that we could not meet in person for long periods of time. Further, during the course of my research project, my family expanded from including one to three children. During my two year-long maternity leaves I wanted to reduce the time I spent away from home; and this, too, limited our opportunities for face-to-face work.

In a January 2024 Zoom meeting, Christian and I reflected together about our work process so far. Our conversation spanned topics such as the limits the pandemic set for our work, the level of initiative each of us took and expected from the other, as well as how we view the legal and artistic ownership of our composition. During the talk, we also came to realize that some misunderstandings arising from our different practices and backgrounds had impacted our communication and process. My transcript of our conversation lays the foundation for this reflection. In the light of our dialogue, I will further discuss the topics of time, improvisation and the artistic palette in our project.

The tape materials of Eiksmarka Omland were recorded at Eiksmarka Church in June 2023 by Espen Reinertsen. In November 2023 the full work was recorded by Vegard Landaas and Thomas Wolden at LAWO Classics for the album Palette.

Conversation: Christian Wallumrød and Karin Hellqvist, 10 January 2024

Karin: Early on in our work process, I shared some ideas and materials with you, including the recording of Emerentia Dialogues (recorded at Stjärnsund mansion, 2020) and materials connected to my background in folk music. How was it to start our process in this way?

Christian: I think this was a very good way to start our work and I welcomed it. I have heard you perform many times in situations where you perform specific, notated things. I feel as if I know your way of performing to a certain degree. Now I got to know you better and learned about what you grew up listening to, who you played with and that you engaged with so many different kinds of music. I feel as if I can hear in the way you perform that you have roots in other places and other traditions. I was able to create a wider picture of what you are interested in when you choose yourself. For me, this became an integral part of the whole project. Further, as I remember it, you mentioned early on that you imagined our work to be connected to things I had created earlier. Specifically, you spoke about the tune Psalm (available on Christian Wallumrød Ensemble, A Year from Easter, ECM, 2005). This acted as an impulse. Additionally, we discussed my personal artistic areas of interest. All of those things together, with their associations and links, were concrete and they had the potential to act as a starting point.

Karin: Yes, and I was also interested in whether the piece could become a kind of duet between the two of us, although you could not perform it with me live. In Eiksmarka Omland, as it turned out with the pre-recorded tape part, I now really try to follow you as a duet partner through this material.

Christian: Seen in relation to open, improvised materials that are not yet defined by notation, how did you experience the fact that the material became very concrete at one point – with a notated melody and a harmonic structure?

Karin: Interestingly, in my overall research project, notation has played significantly different roles. Notated elements have entered at very different stages in the compositional processes. Funnily enough, I thought that notation would enter our process at a rather late stage. I imagined that we would improvise much more. But the parameter of time restricted us. We did not have much time to develop materials in an improvised way. Consequently, we soon reached the core of the piece, the notated melody. In retrospect, I wonder how much I contributed with the me-specific that my research project explores, to the work on the melody? The melody is composed by you. As we recorded the melody for the album in November 2023, it was an exciting co-creative process of looking at the melody from different viewpoints. But I do not think our focus was my intuitive way of performing it? Therefore, I have been thinking about whether this would have been different if notation entered later? I also imagine that you as a composer naturally enough have a certain idea of how you’d like to hear it. It is interesting, this field of tension – what happens if you do not like the way I play it? What happens with the decision making in the work with this melody? As notation enters the collaboration, something happens.

Christian: I suppose there are several aspects to this. When notation enters, as you say, things become more concrete and tied up. There is something very decisive about what is written on the paper. However, for me, notation is anyhow very secondary. It is just a kind of necessity. I think you are right, that my idea of how things should sound can be rather firm. When I compose, I listen for what sounds nice and I try to get away from what I do not find as nice. In this case, I could have decided not to notate the melody. As I use notation, I try to notate as closely to how I imagine it to be as possible. Still, the notation is very limited in detail. The idea here was that I wanted you to play it as you like, with your tone colour and ornamentation. However, there is a matter of definition. I think of the pitches one plays and how long they sound as the central framework of the melody. What do you think of, concretely musically, when you think about playing it your way, with a greater freedom to form it as you wish?

Karin: When we worked with this melody, leading up to the album recording, I already knew it in its basic form; the pitches and their duration. During our work sessions, we discussed my performance of it, twisting and turning performative aspects. We used some adjectives for the way we wanted to form it, for example light. Working that way turned out to make a big difference to how the melody actually sounded. It affected the tempo, flow and level of ornamentation for example. It was still basically the same melody, but the impact of the interpretation made it sound very different. At some point in the process, we got stuck. Then we said – what happens if we now just go back to my intuitiveway of playing this melody? To rather forget what we had just done. Then I played the melody in a more ‘natural’ way and I felt freer with it. It made us realize that we actually wanted a faster tempo and a more flowing feeling than we had recorded previously. In retrospect, how much of this intuitive way of playing the melody actually made it through the process? I think of you as an artist with a strong musical integrity, and in my perspective, you know very well what you think works and what doesn’t. If you experienced that I did not play the melody as you heard it, was it difficult to suggest to me to play differently?

Christian: No, I don’t think so. To me, this rather sounds more like to what degree we have the opportunity to try outdifferent things. There are so many things in a process that impact how much time we have. To me, the best way of working is doing it– trying it, playing it, finding out what works and not. Hands on. In this project, we had several meetings and situations where we could play together and try things out. But perhaps not so much time in relation to the scope of the overall project? I thought all the time that beside this melody part, something more needs to be there. I did not think it was difficult in the situations where we were to form the style of the melody. But think I waited for some impulse or suggestion from you on how to proceed. I was very curious to know how you thought that our process could develop.

Karin: It is good to talk about that! From my perspective, being co-creative with the material is a new situation. I felt that I did make suggestions, like the voicing of the melody parts in the lead-up to the recording in November. The melody then came in three different versions. We delegated the tasks between us so that I was to make counter parts to the melody sections and you would make sketches for the transitions between them. I created suggested counter parts. But it was not my suggestions that made it to the end, you came with new parts. They were very nice! Then, I thought that perhaps they came from an understanding of the melody with the chords that I do not know about. Most likely, you were inspired by what I had done before. I imagined that you had a strong sense of the melody and perhaps you didn’t find my suggestions interesting enough. I became unsure of whether I was ‘allowed’ to fill that space and reluctant to suggest new things.

Further, for the time aspect, there were several factors that contributed to us not having as much time as we both wanted. We live in different countries, there was the pandemic, I was on two year-long maternity leaves and so on. Processes were constantly put on hold. We met to improvise, then a year passed before it was possible to meet again. In the other case studies of my project, some collaborations were rather structured around the fact that we circulated materials between us from a distance. You and I needed to meet to play together. So, I see too that it probably would have been a different piece if we could have met more and been more involved in the doing that you describe.

Christian: Yes, I think so too. And I also see that during this process, the initiative you take or don’t take, is influenced by the signals I send. I sometimes thought that it would be good to have more initiative from you, and I understand that this also can have as much to do with me. It is a two-way thing. It shows us very clearly that different forms of collaboration need different things to develop. In our case, the collaboration is performer-based as I am active in the piece too. Therefore, it is based on the fact that we are in the same room, talking together. I always wished that our meetings could be longer and happen more often, so that we had the chance to find out about things together. Perhaps, those feelings then made me try to take some kind of responsibility for the process to develop. For example, when the recording session at Eiksmarka Church in June 2023 came closer, I thought that it might be good if we had some concrete suggestions, a kind of structure. That idea turned into a few sketches. Again, I was open for those sketches to lead us somewhere else, as an open invitation to something we do together.

Karin: I think the material it generated, the middle sections of the piece, were well communicated as a starting point for something more. I understand that you felt the need to take responsibility for the process and I really appreciate that. I have learnt a lot in this process, as a ‘young’ co-creator and improviser. It is interesting that I feel that I have taken initiatives but experienced those as not in line with what you imagined, and then became passive, while you wish that I would take more initiative and give more input. Perhaps initiatives would be differently distributed if I had written the melody? That is why I think about what happens when notation enters and how it affects me as a ‘classical’ musician. Even if this relation to the score is partly what my research project aims to challenge, it still resides within me, from my education and from my still limited experience of co-composition.

Christian: I was missing that our creative process could as much go the other direction. Now the notated suggestions came from me, but they could also come from you.

Christian Wallumrød & Karin Hellqvist: Eiksmarka Omland I-V (2024).

From Palette (2024), LAWO Classics

Karin: If we had had this dialogue earlier, perhaps the piece would have developed in a completely different way? Developing a piece is a process of searching. I remember at one point we discussed the melody and you said that is was ‘more or less ready’. Looking back at that moment now, I think I there and then got stuck in the thought that this notated melody was the finished main framework for the piece. I did not understand until much later that other materials could enter the piece. I remember us talking about the melody like it was the core of the work.

Christian: That is interesting. It might very well be that I have been unclear regarding how I have thought about the melody as a ‘tune’. When you say this now, I understand that you have thought that we continue working and circling around the melody. That it is the main element and that we find different ways of playing it, or finding ways of improvising around it, all the time based on the tune. I, on the other hand, tend to think, with this kind of closed-form material, that there is not much more to it. It is ready, and I do not have the imagination to develop it further.

Karin: So, we have had rather different views on what function the melody had and how to continue working with it. We also have different ways of working with materials. I come from a practice with over-layering materials through my work with technology. In our case, I thought that we now had the core material, and we will rework and experiment with in different ways. I now understand that you thought that it acts more as an impulse to other kinds of materials. It is interesting that we have had such different ideas of what role the materials we started with should have onwards. It is also a matter of communication. When two people work together and aim to evaluate things collaboratively, one person might take for granted that a certain material was merely a part of the process, while the other may not share the same view. I see that our thought-processes have been different. I became confused about how I should continue working. To me, this says something about the role as a classical musician that I bring to collaboration. It is not meant as a way of saying that you should have done things differently.

Christian: And if so, it is not a problem either! I have things to learn too. It always has a consequence how things are being communicated. The material we worked with just before the recording in Oslo was based on a rather unhelpful notation from my side. I intend there to be a high degree of improvisation on that material, but I had to use some form of notation to describe my ideas. I think it is worth noting what happens in the space where I quickly try to notate something this way. To me, the result is not primarily notation. It is just a way of suggesting – can we try this or that? It is destined not to become exactly as I imagine it, because the description is so open. However, I think this exchange worked well. You made your solutions to the notation, as you tried to decipher it. It actually resembled very well what I tried to say in notation too. But how did you perceive this way of working?

Karin: I agree, I think it worked well as a way of experimenting. I do not think your notation was that unhelpful though. It efficiently communicated openness. I remember that finally, we decided that – okay, now I have tried out the suggested pitch material, so I know more or less what it is. Now, we instead put notation away to give space for an improvisatory process during the album recording. I would wish more of those elements could have entered our process earlier. To circulate this kind of material more between us.

Christian: I agree. And this is on the one hand the backside of the material becoming a ‘tune’. Anyhow, this later work method felt like a true co-creative process. It became an improvisation within a very clear framework.

Karin: Finally, regarding the ownership of the work. How do you structure ownership in the Christian Wallumrød Ensemble?

Christian: I think very concretely about what the sounding result of the process is and how it is created. Oftentimes, I have created most things, if not all. Other times, I hear that the specific things another musician contributes with has a profound impact on how the result turns out. Then, I try to set a percentage to divide what I consider the outcome to be. The times we improvise together, I just make an equal distribution of the ownership between us.

Karin: Over the course of my research project, I have come to consider ownership in new ways. One way of seeing it is seeing music as a result – what ended up in the work and who made the decisions? Another way of seeing it is the process-oriented view. How do we together propel a process forward, how much do we participate in the process itself? When thinking about ownership in our case, I can see that you composed the melody and also structured the middle parts in notation. On the other hand, the process toward that was a collaborative endeavour. What I have contributed might not end up clearly visible in the notation. But my contributions have taken us to the results, along with yours. Therefore, I suggested sharing ownership by 30%/70%. What do you think about this?

Christian: I think that it is fitting, considering both process and result. When I think about how the different parts are constructed in our work, I see it to a large extent as quite conventional. In the melody, I take a lot of decisions and they become a large part of the piece. The middle parts are created more collaboratively, where we have contributed equally. We also improvised things on top of this. You compose it through playing it, there is evaluation in that. Considering that the melody I composed takes up a lot of space, I think 70%/30% as a whole reflects somewhat what we did. Seen with a pragmatic view.

Karin: I am in a process of considering a layer beyond the concrete, pragmatic view. A layer that is not seen in the score. I explore an expanded view on ownership. For example, the folk music I shared with you in the initial phase of the work – this is not seen in the final product, only we know of it, but it contributes to the final work. When entering a collaboration, we share a common world, common time and the common will to do something. Can this be reflected in the ownership and have something to say as much to say in the final, concrete score? Within classical music, we are not used to thinking like this. There is very rarely legal ownership for performers who actually do collaborate. Opening up to acknowledging those impulses and contributions in the process is a way of starting to see its value, showing what performers bring into the work.

Christian: Yes. It is a great point coming out of a practice that is inherently unfair by tradition. I suspect that the thoughts that you share here can help break those structures.

Karin: Yes. Then we also live in a world designed so that we need to register legal ownership of works and then we get some money when those works are performed.

Christian: It is also connected to identity and role. It can be somewhat challenging to give away the privileges one has of ownership. Composers have long traditions of seeing themselves as different from performers. All things that contribute to challenging those ideas are welcome.

Reflections around the work on Eiksmarka Omland

Time and priorities

In our conversation in January 2024, Christian and I both mentioned that we perceived the time to work together as limited. The pandemic and my two maternity leaves restricted how much I could travel to see Christian. Further, Oslo is my ‘research city’, where I am a research fellow at the Norwegian Academy of Music, while my family is based in Stockholm. Therefore, I did not feel that I could ask Christian to travel from Oslo to Stockholm to work with me as this was not mentioned in the premises for the collaboration from the start. In the later stages of my project, the work on some of the other collaborations intensified, and as a consequence, I had less time to work on Eiksmarka Omland. I became busy with the time-consuming work on Solastalgia, One and the Other (Speculative Polskas for Karin) and Gradients, as well as the process of performing and writing about the already finished works in my project. Eiksmarka Omland is a performer–composer-based work, which, among other things, means that it is created by two performers who are busy performing. Beside my fellowship activities I had a concert schedule to prepare and Christian was performing and touring a lot too, with focus turned to other processes and materials.

All five case studies in my research project were created partly during the pandemic and around my maternity leaves. However, the projects that could nevertheless flourish the most are the ones that generate new work methods developed to deal with the premises. In the process of composing Eiksmarka Omland, the physical meeting between us as two performers was at the core, and we did not wish to compromise too much with that. Thus, we waited, and the pace of our work became somewhat slow from the start. As a consequence of those different time-related circumstances, the work on Eiksmarka Omland was put on some kind of lukewarm hold between our spread-out meetings. As I experienced it, Eiksmarka Omland never really took centre stage in my practice, and perhaps didn’t in Christian’s either.

The fact that Eiksmarka Omland developed at a slow pace may further be connected to some misunderstandings that we discovered in our conversation. I believe those misunderstandings were related to us both being rooted in different practices and artistic fields each of which comes with preset expectations and work methods. The melody that Christian composed early on was for him one of many possible sonic modules in the process toward a piece. I, on the other hand, interpreted it as the overall framework and core of the piece. In retrospect, I see this misunderstanding lingering as a question-mark between us: Christian waited for me to take initiative to create new materials and I waited for us to keep working on the melody.

Improvisation and efficiency mindset

During the work on Eiksmarka Omland, I sometimes felt insecure when entering the territory of improvisation. Prior to my fellowship period, I rarely engaged in improvisation. However, during the research project, I started to improvise more often in different settings and I began developing an understanding of myself as an improviser. Even though I felt that Christian and I were creating together a generous safe space, I sometimes had difficulties connecting to my creativity in our improvised sessions. Perhaps this was because I felt as if I entered Christian’s creative domain and practice rather than us exploring new territory together? I sometimes became judgmental toward my young improvisatory practice instead of focusing on the creative act of improvisation.

At times, I also felt somewhat fenced in by an ‘efficiency mindset’ that I connect to my classical performer’s role. When having several demanding pieces to study as a soloist or in an ensemble, an efficiency mindset can be beneficial, or even crucial in order to learn the music within the given timeframe. The ability to estimate how much time and what approach a certain work needs in the practice room is a skill that I have developed over the years. I earned the sensitivity of estimating the workload connected to different musical styles and notational approaches. The analytic efficiency mindset wants each work session to lead to concrete results or improvements according to my estimations.

However, in the case of Eiksmarka Omland, our process was one of searching, experimenting, and improvising. Being results-orientated seemed to stifle the emergence of new creative possibilities. My creativity in the context of Eiksmarka Omland needed time to develop, or to suddenly show up. My efficiency mindset would at times challenge this space for reflection and pondering. Our improvisation sessions included elements of not-knowing and of artistic evaluation in the moment. My aim to be fully present in such a process provided me a challenge to grow with. Sometimes, improvisation offered me a space to let go of my doubt and experience joy and surprise in the moment, able to connect to my inner voice, preference, and taste. Other times, my mind was somewhere else, occupied with a future result.

The artistic palette and Eiksmarka Omland

What happened to the artistic palette during the work on Eiksmarka Omland? When improvising with Christian, I used a web of abilities drawn from the embodied, contextual, intuitive and relational dimension of the artistic palette. The act of improvisation connects me to my resource of embodied knowledge. It includes the patterns of my inner reactions, ways of phrasing, intuitive ornamentation and my sense of musical pace. Improvisation is further constructed in my communication with Christian and is situated in the context of the artistic material. It connects me to intuitive decision-making and is related to my desire to develop the musical work. When engaging in improvisation, I develop skills connected to the moment; pre-reflective abilities of instant evaluation, response, and decision-making.

Eiksmarka Omland, as a duet of two performers de-synchronized in time, requires that as I perform the work, I relate to Christian’s interpretation of the melody in several sections of the work. It is not a live interpretation that Christian plays in the moment, but a reflection of it, fixed on a tape part. Precisely following Christian’s pre-recorded lines while connecting to my intuitive way of playing the melody is a challenge that requires practice. Carefully following the pre-recorded tape part feels somehow similar to following a strict score in the classical music tradition; I have limited leeway. However, I do not want the exercise to be all about being ‘correct’ in the timing of the tape. I want it to be a space where I feel free to shape my performance in the moment. Practising the material toward its performance in September 2024 therefore became a process of internalizing Christian’s interpretation through repetition. In our album recording session in November 2023, I noticed that the times I felt most connected to the artistic palette, were in the freer parts, where notation was set aside, and I related freely to the tape part. I now want to experience the same level of freedom in the more carefully notated parts, where I follow Christian’s line. When negotiating my space in the set framework of score and tape, I use the artistic palette to develop a way of being free and creative in my performance. Not able to change the tempo of the tape, I instead explore and refine other layers of interpretation as ornamentation, timbre, and phrasing. Despite the strict framework, I feel I can challenge myself to not fall into the mindset of the faithful classical performer.

A spark for collaborative work?

Eiksmarka Omland may not have been created through the most continuous shared work process of my research project. However, the process comprised far more interaction between us as participants than most works created in my pre-research repertoire, and the interaction provided me with experiences to learn from. The work process offered me a space to reflect about myself and my artistic palette in the framework of improvisation. Already from the start, I learned to share the responsibility of the imaginative process together with Christian. Questions about decision-making and notation turned into an enlightening discussion around ownership. Some central turning points in our shared work process were not discussed in depth along the way. Thus, a few decisions evolved from suppositions and misinterpretations rather than actual artistic opinion. As I assumed that I understood what Christian meant, I accepted it as his decision, instead of raising it for further discussion. In line with a more passive classical performer’s role, my creative space was restricted. By reflecting around this process, I have learnt the importance of discussing expectations and work methods early on.

In my research project, some case studies continue to develop working partnerships where shared creative work has already unfolded prior to my research. Both Carola Bauckholt and Henrik Strindberg have written solo works for me as a result of creative processes during which we have come to know each other, and I have had an active role. I have premiered Liza Lim’s work in ensemble settings and performed other works by her. The research collaborations of this project with Carola, Henrik and Liza have all provided very rich shared processes. Am I perhaps more likely to develop fully collaborative work when there already is such a connection established? In the beginning of the work on Eiksmarka Omland, I knew Christian through his music. However, I had very little insight into the practical way he works, and we had never worked together. Today, I know much more about his practice. Through our process, I have learnt more about my own practice too. Perhaps Eiksmarka Omland can spark further creative and collaborative work, building on to the new knowledge and understanding we have earned through the process of creating it.