"Art is a kind of expression.

Good art is complete expression.

The work of art is the object seen sub specie aeternitatis (from a universal perspective); and the good life is the world seen sub specie aeternitatis. This is the connection between art and ethics."

Ludwig Wittgenstein, The Collected Works of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Electronic edition. Notebooks 1914-1916, 84.

Who is afraid of the female nude?

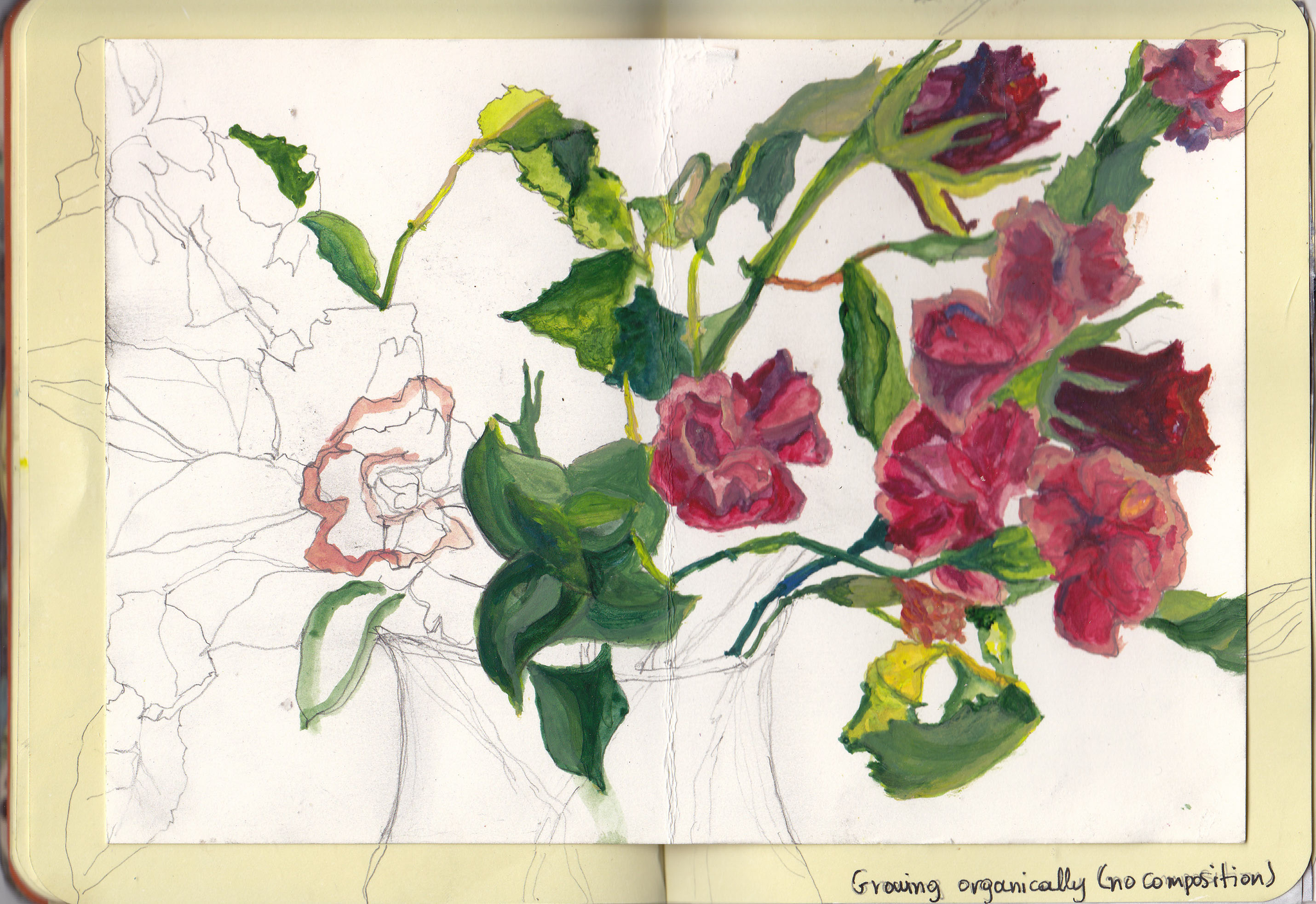

Contrary to the clothed body that is a symbol, meaning a conventional representation of something, the naked body is a sign, which means something specific, concrete and unambiguous, a form of language that communicates directly. The female nude has established a long history in academic painting and sculpture, where it is often portrayed in classical proportions to convey the illusion of realism. Academic painters typically used gridded preparatory drawings, as a technical device, to transfer the image they wanted to paint onto canvas for the final work. In his numerous drawings and paintings of the turn of the century Vienna, Egon Schiele repeatedly dealt with the problem of representing the female nude. His depictions are unrealistic, for his time, images of females with elongated limps in unusual and awkward positions, drawn directly from life usurping classical perspective.

Characteristically, in his Danae (1909), despite the Expressionist effort for realistic representation, Schiele’s unrealised project of painting the female nude in a classical manner, ended up with a painting of flattened perspective and large colour patches, resembling a rather romantic and pre-modern representation. However, as it is evident in the preparatory drawing, where Schiele attempts to follow classical perspectival rules and to lose his nervous drawing line that later became his artistic signature, the Neo-classical tradition shows as the other side of Romanticism.

Designed diverting from the grid, Mies Van De Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion, built and taken down between 1929 and 1930 to be rebuilt in 1983-86, contains a single sculpture of a female nude, separated from the viewer by a wall panel and a pool of water. The statue is a memorial for the only female amongst a group of students, who, during the Spanish civil war, were captured and tortured, resulting in the woman’s death. Although the sculpture is made in the Neo-classical tradition, the pavilion’s own diversion from classicism creates a semi-labyrinthine physical experience of the architectural space, which demands from the visitor to orient themselves among side the luxuriously cladded wall panels and the minimal furniture, in order to get a view of the female nude. Depicting a woman with her hands in the air, as if she is about to get shot, standing in the middle of a water pool, thus unreachable to the viewer, the statue earns the status of the sacred, although it bears no religious, or even remotely Romantic, connotations.

The religious and the sacred

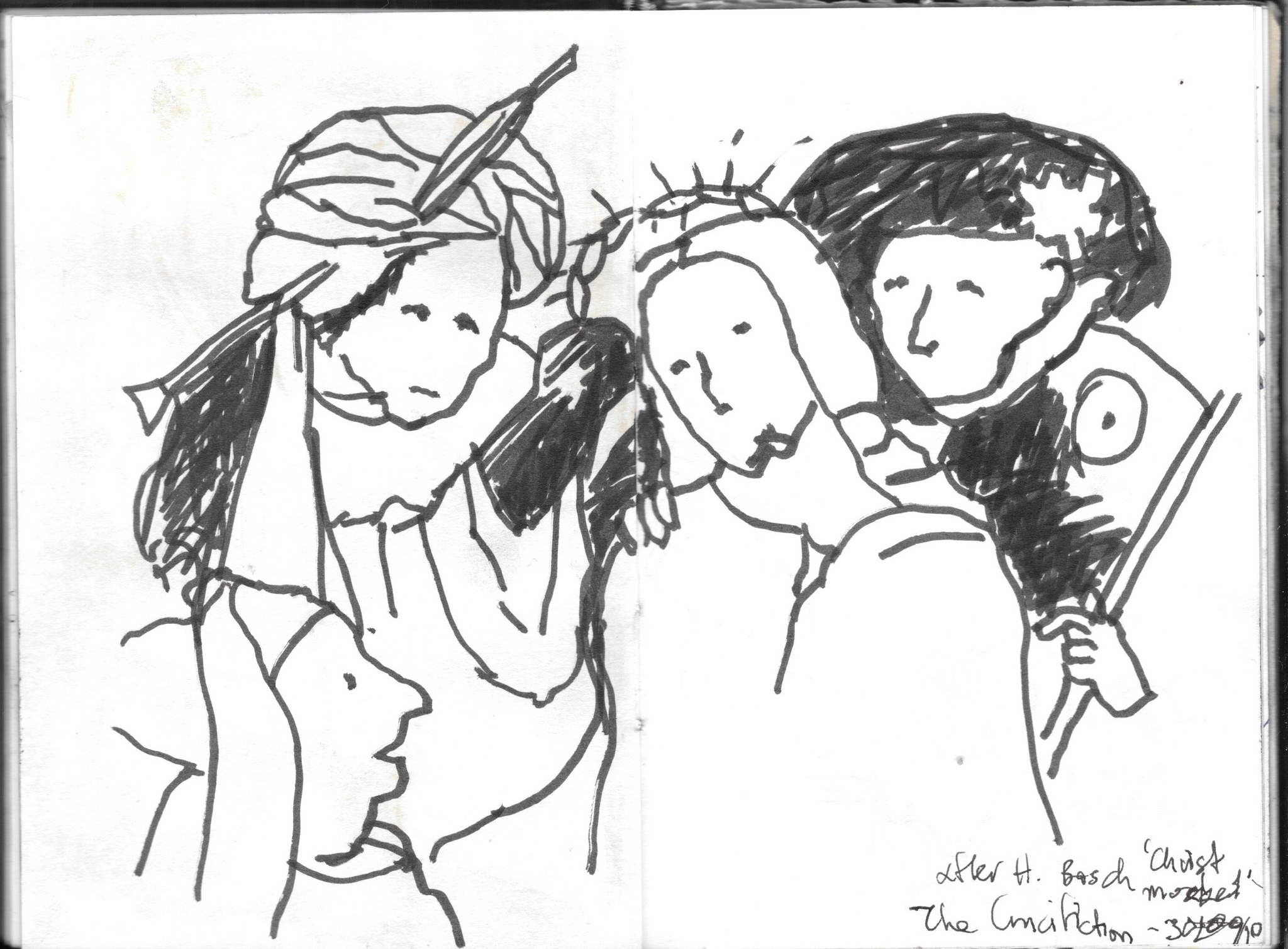

It has been argued that, in the fine arts, religious symbols have long lost their initial connotations with spirituality; instead, they have largely become signifiers of a middle-class lifestyle. As McGowan (2008: 55) has noted, the shifting meanings of sacred/religious objects, in particular the recent phenomenon of sacred/religious objects turned into fine art commodities, has introduced new ways for their valuation by virtue of their secularisation and commodification.

Religious art has always been commoditised; for instance, in the 1400s Florence, “it was common practice for churches to sell altar naming rights” (McGowan, 2008: 58). Throughout history, many religious objects were sold as commodities in markets for common people, who understood the simple images they conveyed. On the other hand, Renaissance artists, who wanted to display their skills to their patrons funding their artistic endeavours, to display in turn their wealth and prestige (McGowan, 2008: 58), produced more elaborate works decorating the devotional buildings of that period. In the contemporary context, where past religious art is routinely exhibited in museums, no longer serving their initial devotional function, the religious has been separated from the sacred: “The very nature of a museum implies that objects have been detached from their original contexts” (McGowan, 2008: 60). In this context, the very nature of the ‘sacred’ is not incompatible with museum or the art gallery’s aesthetic values, where objects are exhibited outside their original contexts, forming an alliance of aesthetic qualities with the sacred (McGowan, 2008: 61).

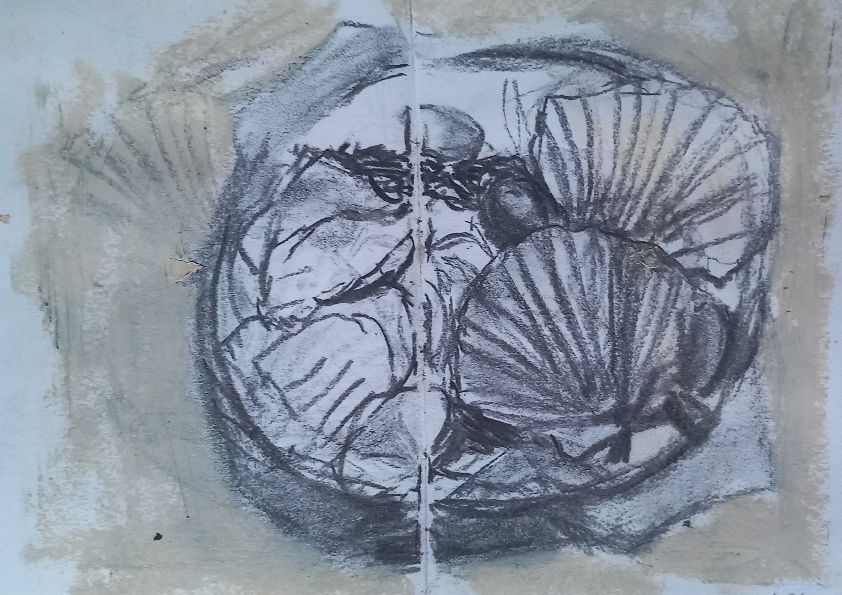

For example, “The body can be seen as a means for religious redemption” (Braddock, 2008: 150), referring to Andres Serrano’s work “Piss Christ” (1987), portraying a small statue of Christ on the cross deeped in a urine sample vessel. Serrano faced accusations of blasphemy, however, as the artist himself points out, this argument is paradoxical, because his ‘membership’ to the Christian Church as a Catholic would disqualify him from committing blasphemy.

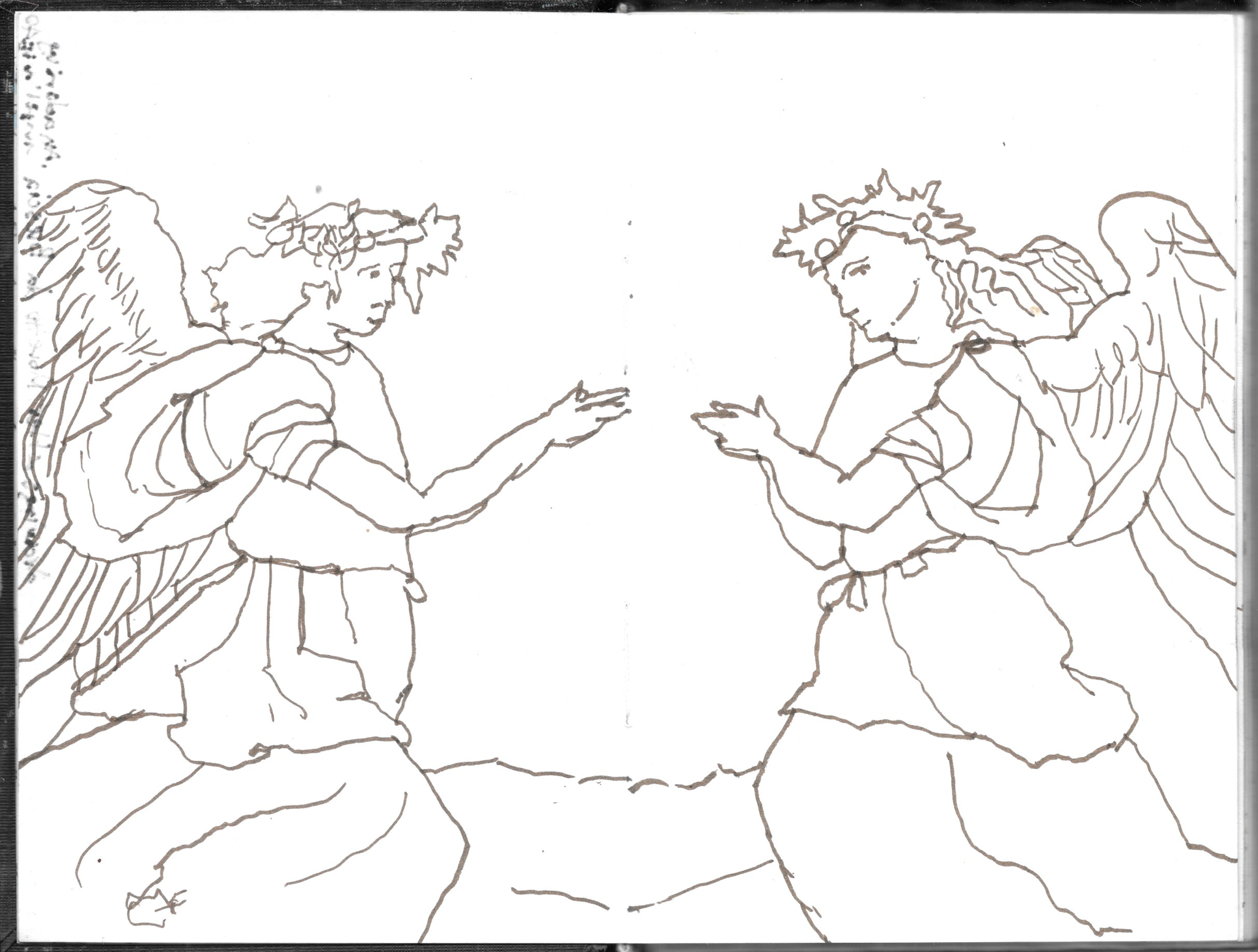

Discussions about the context where old and contemporary artworks are shown have been controversial. Arguably, the art gallery is “a site of questioning and critique, not a site of devotional practice”, as Braddock (2008: 153) notes, where artworks addressing religious imagery can put forward alternative to the established views about the symbols of devotional practice. On the other hand, taking that “A religious painting in a church could also examine or tease-out the nature of [religious] beliefs” (Braddock, 2008: 153), we can reappraise our understanding of binary imagery “misunderstood by essentialist religious paradigms” (Braddock, 2008: 158).The body can be reappraised as not primarily sexual or abject (Braddock, 2008: 158), but as sacred, signifying the search for spirituality beyond profanity. This view encourages us to think of artworks exhibited and archived, aside of as material artefacts, also as memorials, as well as visual memory (McGowan, 2008: 61). One could say that these are the characteristics of the Barcelona Pavilion statue, taking that Romanticism advocated "the religious mission of art and the visionary vocation of the artist" (Jones, 2020: 32).

The female artist as model

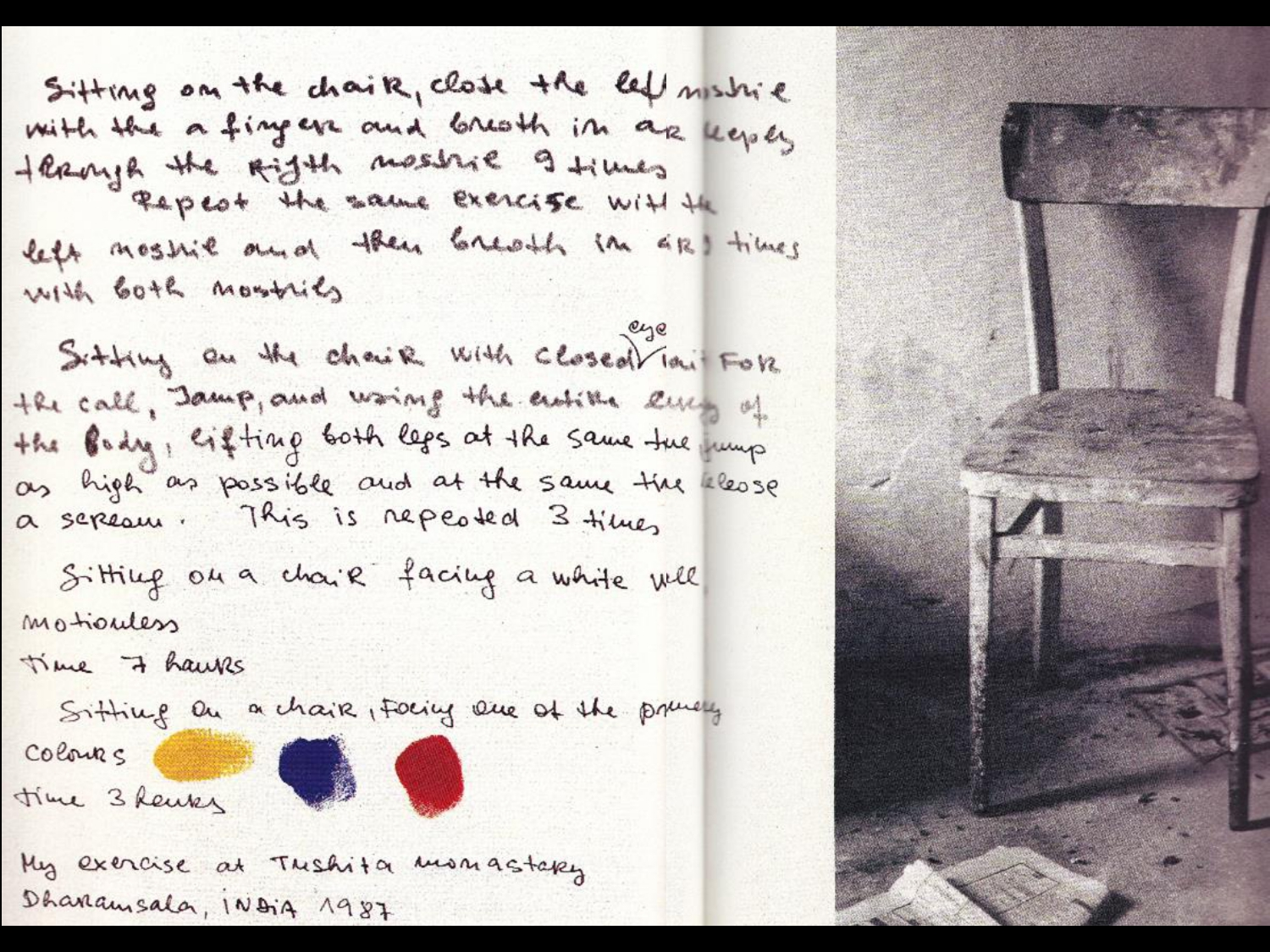

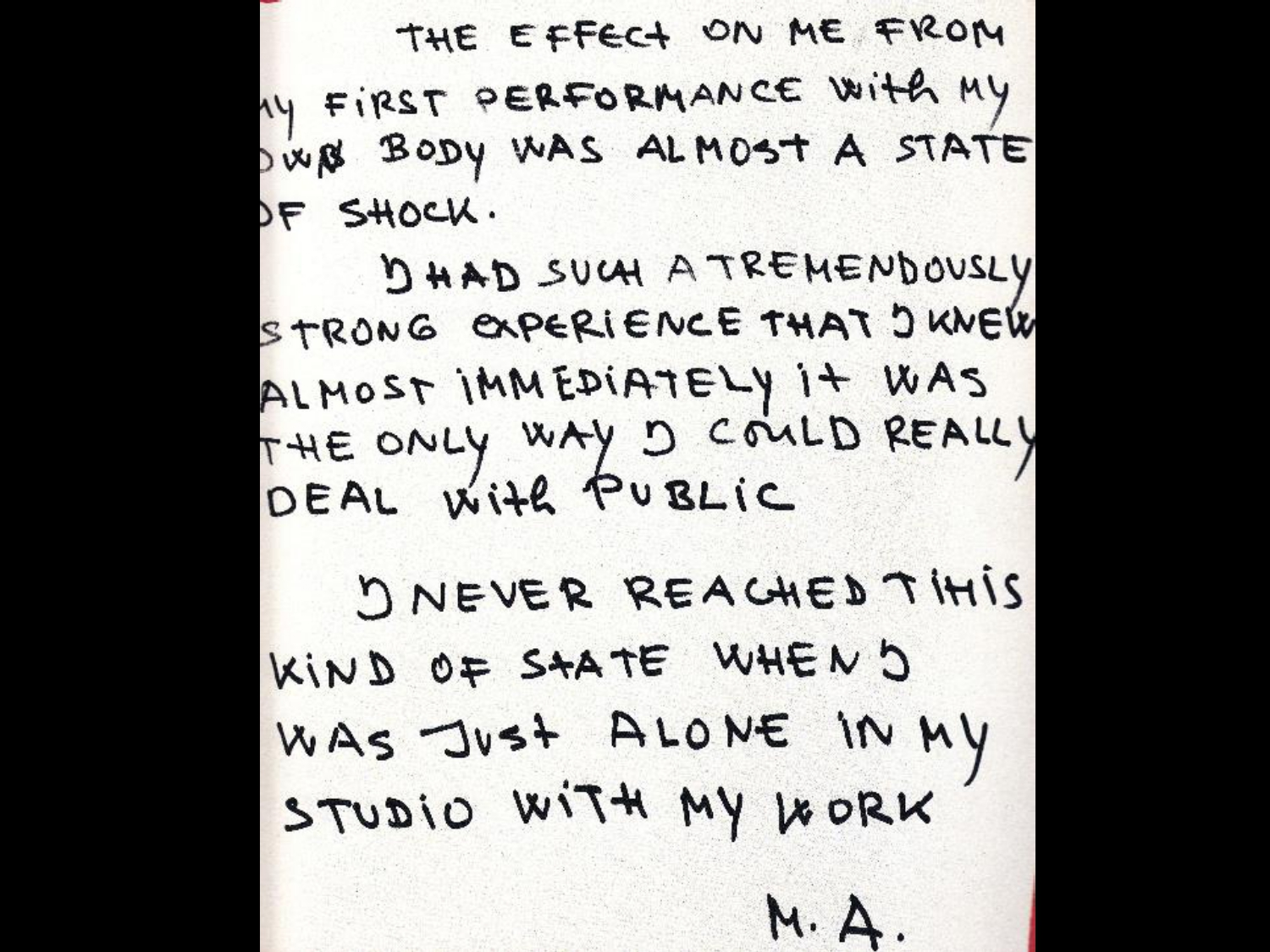

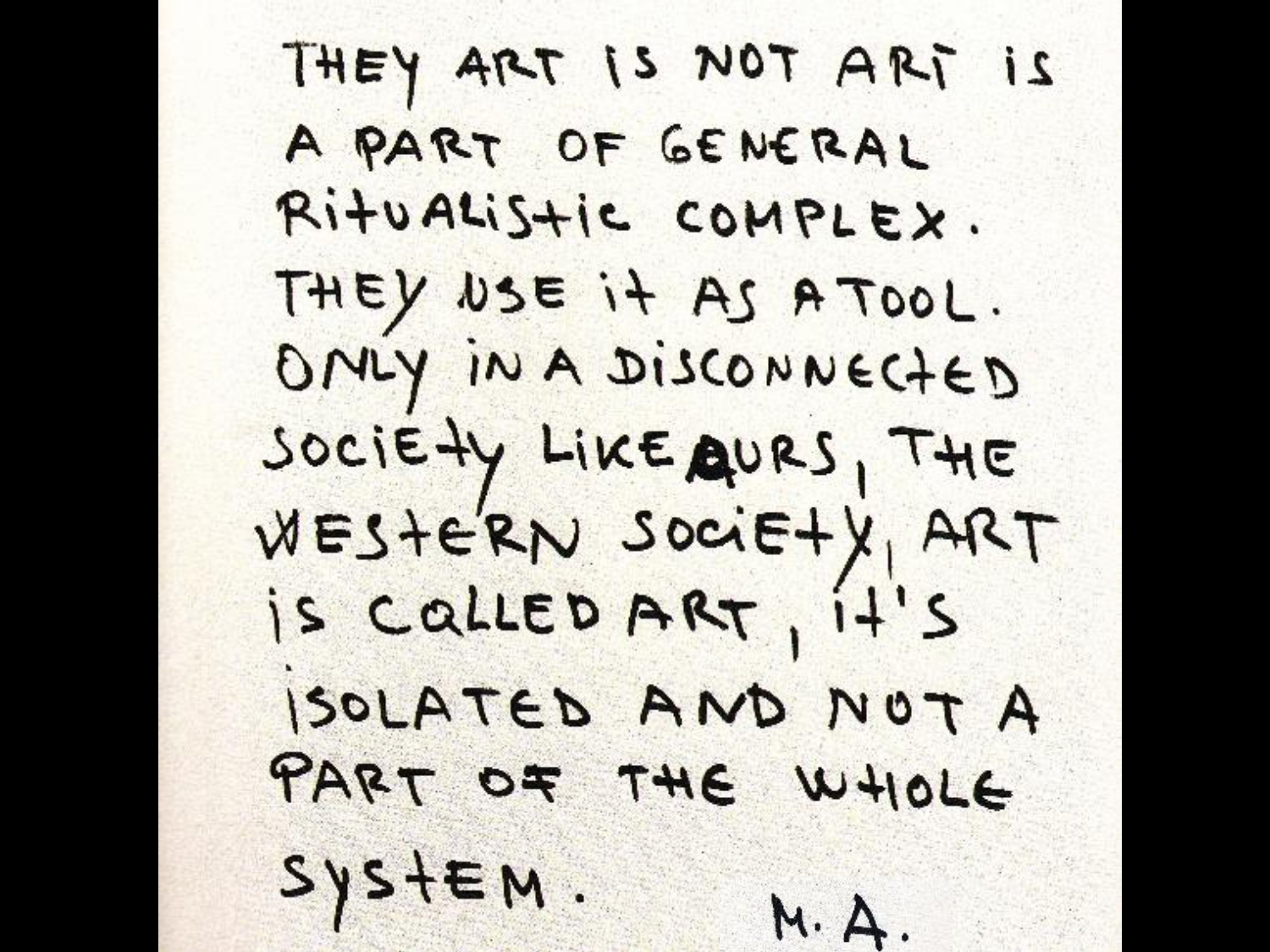

In contemporary art, there has been considerable controversy around female artists including themselves as the female nude in their work. Besides performance art, with the well known example of Marina Abramovic in her solo works and in collaboration with Ulay, other artists, such as Pipilotti Rist and Tracey Emin working in video art and in painting, have used themselves as the female nude in their works, without adhering with the artistic principles of performance art. As a more “formalised and abstract discipline” (Jones, 2020: 39), performance art has accompanied the artist’s performances, using their own naked body as medium for artistic expression (Rico, 1998: 46) and employing sculptural objects often incorporated in the performance or exhibited separately. For example, Abramovic, who travelled extensively in non-Western territories whilst producing her performances, made in the 1990s what she called ‘transitory objects’ (Rico, 1998: 78). These are rather process art objects, influenced by Abramovic's stay with aboriginal tribes and made in a performative manner, which are there to trigger the artist’s performance, as well as the art viewers’ interaction with the performance and the objects. The 'transitory objects' signal the artist’s physical transition from one place to another (Rico, 1998: 85) that for her is indispensably connected with her idenity as an artist, but also a recent artistic phenomenon: "There is quite a large group of artists who actually have become real nomads. The planet is the space where things happen. There is no longer any idea of borders, cultures and nations. They are all dead. The artists are functioning in-between everywhere" (Rico, 1998: 62).

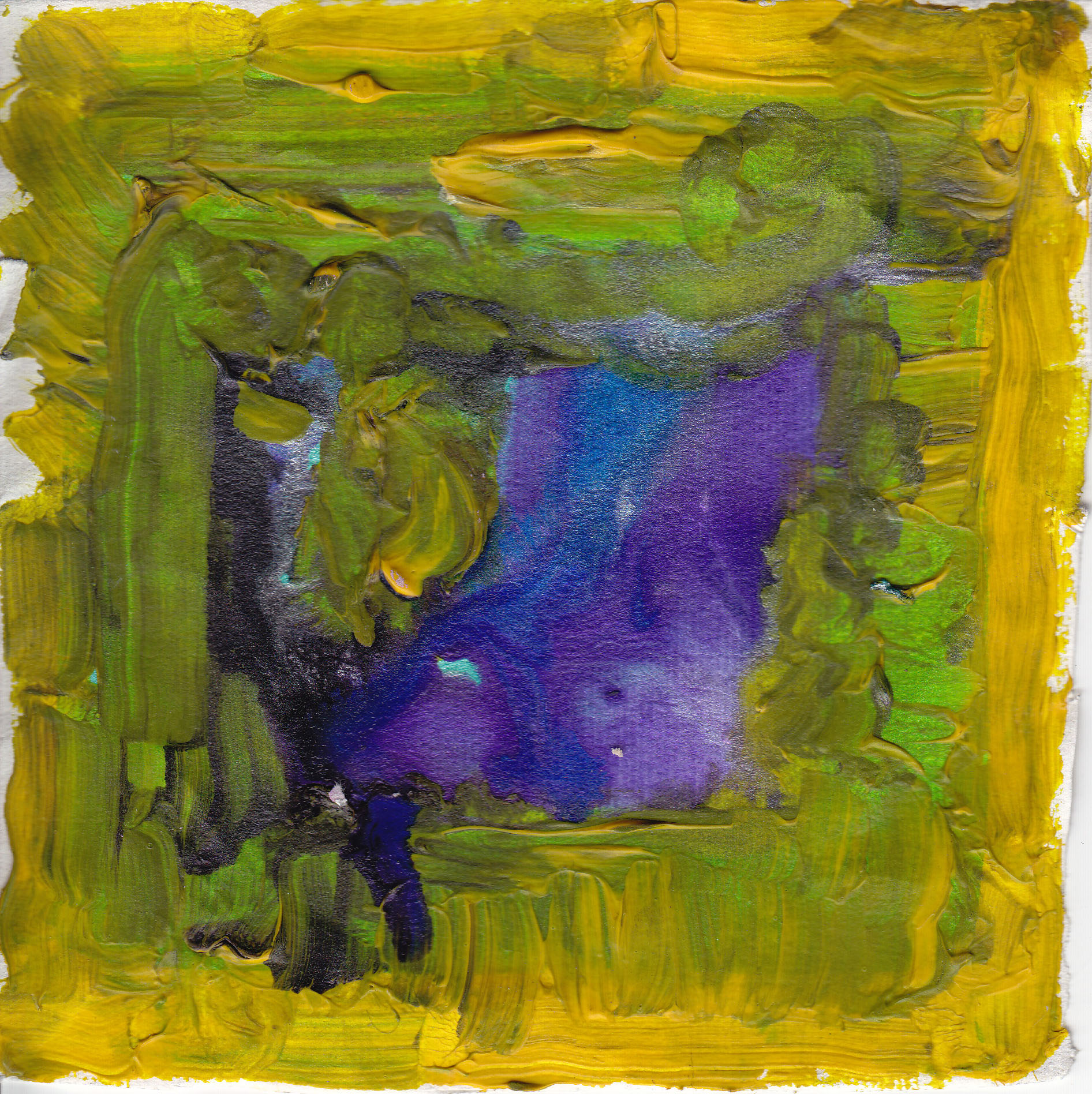

I tore the canvas and covered it with plaster to make a suspended structure for installation objects. The installation was never materialised, but I discovered a new technique of working with canvas and plaster to make sculptural objects.

The article was initially presented as a conference paper on Marina Abramovic, at the Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven, 2010. I was invited with other international speakers. I was there for a week on a Greek visa. In 2011, I became British national by naturalisation.

"Betty Nigianni" was my authorial and artistic name; also a name I have been known as (aka), included in my British citizenship application as such. I used this name as an artistic pseudonym to exhibit and publish for some time, because it designates a non-citizen: literally speaking, there is no citizen anywhere with this name. However, as an artist and intellectual, I hold the intellectual property rights for all works published and exhibited in this name of mine.

On the other hand, Rist has made videos of herself taking the role of the naked model. Selfless in the Bath of Lava (1994), where there is a visual reference to Schiele, portrays Rist above a bath of fire and “was installed beneath a medieval sculpture of Madonna and Child” in Zurich, bearing obvious “religious implications” (Phelan, 2001: 72). Rist’s use of the indexical ‘you’ in her video’s script addresses both a god, in the context of Christian iconography, but also the “(male) art viewer” (Phelan, 2001: 72). Emin has notoriously exhibited herself as the female nude par excellence in much of her drawings and her latest paintings. Although she doesn’t adopt performance art’s strict artistic vocabulary, as Jones (2020: 82) has argued, Emin uses her own body as a form of expression, but also of communication with the public. This became evident in her early series of photo works The Last Thing I Said To You Is Don’t Leave Me Here (The Hut) (2000), where Emin “poses nude inside a decrepit beach hut” (Jones, 2020: 82), purchased with fellow artist Sarah Lucas, to portray her own vulnerability. Schiele has been a long lasting influence for Emin, from her early works to her latest abstract paintings that she exhibited in 2015 alongside her old hero’s work at Vienna’s Leopold Museum. In whichever artistic manner, style or process women artists have included themselves as the female nude in their work, it seems that there is an underlying search for the artist’s identity and their relationship with the art viewer in the contemporary context. In this context, the female nude, exhibited in the museum and the art gallery, achieves the status of the ‘sacred’, whether there are obvious religious significations or not. I mention those female artists, because I have been influenced by their artistic iconography: references crop-up here and there in my own artistic practice. Specifically Emin was very inspirational to me, when I decided to settle in the UK circa 2006, living in Walthamstow, and I first came across her art.

Abramovic championed a new lifestyle for artists, which was unconventional for her time, and specifically challenging with respect to her own performance art work. However, outside Abramovic’s very unique approach to art making intimately linked with her nomadic lifestyle, the culture of artistic nomadism has since developed: in the informal way of participating in workshops and traveling to view or to show in exhibitions and art festivals, as well as in more formal ways, by taking on artistic residencies or formal education.

This exposition was prompted by fragments of the research I carried out between 2010 and 2011 for a public installation project. That project was never realised due to the lack of public funding, which the specific project demanded. The realised fragments were made in the studio, developing material produced through my participation in urban research workshops. The completed fragments, initially prepared for the installation, have been archived at AUP-eflux archive, under the thematic of unrealised projects. However, the exposition prompts us to think and to question, in the example of Abramovic, but also numerous artists like Emin and Raoul De Keyser, who didn’t embrace performance art stemming from the 1960s, choosing to work instead in the tradition of painting and the purposefully incomplete, the following: when an artwork is considered research, meaning work in progress, and when it’s completed. These artists have taught us that is the artistic decision. Finally, the exposition questions whether art pieces made for a larger installation project can be seen as having their own artistic value, taken as separate artworks, which can also potentially comprise of a different art installation; or simply exist as art objects in the archive, serving as memorials and as visual memory.

Memory 2:

In my architectural education, video was taught as a subject in the plastic arts. It was the only subject offering a free topic for the student to choose the theme and the project - unlike the rest of the optonal fine arts training that had set portfolio demands in the academic tradition. The female to male ratio was 7:3. There was one student who originally came to Greece as a political asylum seeker from Kurdistan.

In the recent art history, we have witnessed conceptual artists working extensively with photographs as means of recording their final art pieces, with the photographs in turn exhibited as the artwork itself. In view of this practice, also taking into consideration contemporary artists’ typical nomadic lifestyle that prevents them from keeping and storing artifacts, I want to suggest that online art archives nowadays equally serve the function of the museum and the art gallery, the main difference between the physical and the online space being that the second doesn’t address the art viewer with the material artifact at hand. Nevertheless, as McGowan (2008: 61) has argued:

“The power of the gaze is created and deployed by the gaze. As such, the image is appropriated by the social operation of seeing…the power of images ‘cannot be thought of apart from the desires, needs, projections and learned expectations of their viewers’.”

The visual arts are essentially what they are called, visual, intending to enact and direct the “sacred gaze” of the art viewer, “ruled by protocols that demand a particular performance and response from the viewer” (McGowan, 2008: 62). I suggest that this is fertile ground for further discussions already taking place about the intimate relationship between the art viewer and contemporary artworks.

References

Braddock, Christopher, “Blasphemy and the Art of the Political and Devotional”, Elizabeth Burns Coleman and Maria Suzette Fernandes-Diaz (eds.) Negotiating the Sacred: Blasphemy and Sacrilege in the Arts II (Canberra: ANU E Press, 2008) 147-159.

Jones, Jonathan, Tracey Emin (London: Lawrence King Publishing, 2020).

McGowan, Dianne, “Materialising the Sacred”, Elizabeth Burns Coleman and Maria Suzette Fernandes-Diaz (eds.) Negotiating the Sacred: Blasphemy and Sacrilege in the Arts II (Canberra: ANU E Press, 2008) 55-65.

Phelan, Peggy, “Opening Up Spaces Within Spaces: The Expansive Art of Pipilotti Rist”, Pipilotti Rist (London: Phaidon, 2001) 34-77.

Rico, Pablo J., Marina Abramovic: The Bridge / El Puente (Milano: Charta, 1998).

Wittgenstein, Ludwig, The Collected Works of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Electronic edition. Notebooks 1914-1916 (Amsterdam: Intelex Past Masters, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 1989-2009) 2-91.