In Germany, the musicians and composers changed slowly to the new instrument, for instance, the first application of the valve horns in the orchestra in France was in 1835, while in Germany, Richard Wagner asked for it for the first time in his opera in the Rienzi in 1840; but other composers, as Robert Schumann, started to use the instrument regularly just around 1850. Despite this 'late' revolution, the chromatic instrument quickly became commonplace and was adopted by the Germans much more quickly than in France. From 1848 on, all the composers started to involve it more and more in their compositions, and the musicians started to be more familiar with it, some of them became very successful soloists with it, like the Schunke and Lewy family. The new treatises had a different section for the valveless and for the valved instrument. But, they did not forget the natural horn, the different crooks, and all the connected features. In the instructions they also give sound for this point of view.

Unfortunately, the German teaching literature is not as big and rich as the French, therefore it is difficult to find the information about the valve horn, and about its use. The other aggravating factor is that the few that can be found are divided into two time frames, except one work. One is at the middle of the first half of the century, mainly between 1820 and 1830, the other is from the end of the century, from 1880 on; and the exception is Henri Kling’s Horn-Schule which was, according to his obituary, first published in 18651 2 which is quite close to the discussed date.. Hence, we have barely any information from the time when the valve horn really started to be the standard instrument of the hornists. We have only information about the time when the valves were invented, and the instrument started to become known, and after the time of the revolution when almost every musician used the modern horn. Luckily, these musicians, Oscar Franz, Franz and Richard Strauss, Richard Hoffman found it important to mention both types and they also explained the differences, advantages and disadvantages of both instruments. Even though these treatises were completed some decades later than the time of Schumann’s revolution, it is important to study them, since the authors were the most prominent players and teachers of the period from 1850 to 1890.

In music, especially in music history, we talk about different schools, and different ways of composing, playing, and performing. These different ways of thinking about an instrument, or about the genres made many different kinds of interpretation. This had an impact on the new inventions too. In the history of the horn, we talk mostly about French and German-Bohemian style of playing. This was also the case after the invention of the valve horn. While the German musicians started to use the new instrument more and more, the French, especially the Pariser, hornists tried to avoid the instrument as long as possible. That is the reason that the main instrument at the Paris Conservatoire was the natural horn until 1903, and before it, there was a piston horn class only for 31 years (1833-1864). This huge result was Joseph Meifred’s achievement, who is maybe the best known French cor á pistons player from the first half of the 19th century.

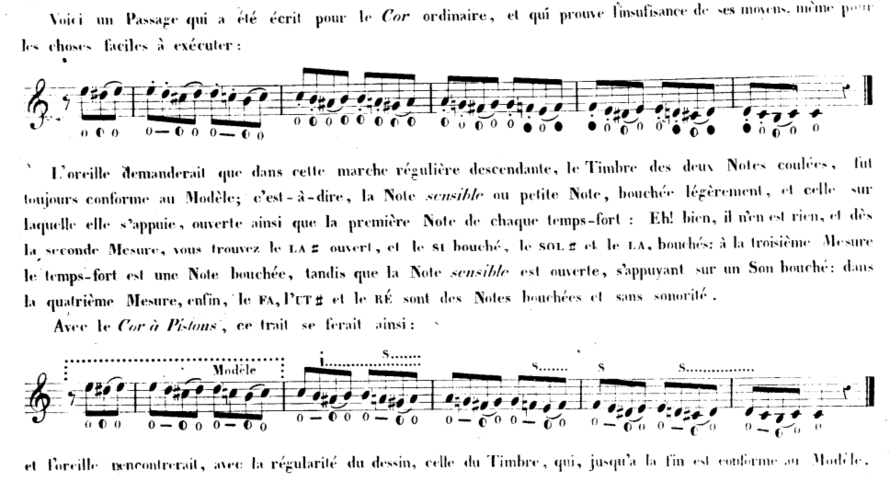

Joseph Meifred was a student of Louis Francois Dauprat, who is one of the three famous hand horn teachers from the Paris Conservatoire. He published the Méthode pour le Cor Chromatique ou á Pistons in 1840. The main difference, that one can notice, between this work and the German tutors, like the one from Andreas Nemetz, is that he used the horn with two valves. That means that he did not want to completely avoid the hand technique, and the different sound colours, and characters that can be produced by the hand stopping. We can also see in the exercises, that he does not mark the fingering for each note, but a mixture of the two valves, ‘i’ for inferior (half step), and ‘S’ for superior (whole step), and the degree how much the bell scold be covered by the hand. As it seems, he tries to not close the bell completely, but finds it important to use half stopping. He also mentions it among the five disciplines what he finds important when one performs on the new horn:

-

To give to the horn the sounds it is lacking;

-

To re-establish proper intonation to some;

-

To render notes that are muted sonorous, all the while preserving those which are lightly stopped, for which the timbre is very agreeable;

-

To give the leading tone, in whatever the key or mode, the countenance that it has in the natural range;

-

To not deprive composers of crook changes, each of which has a special colour.3 4

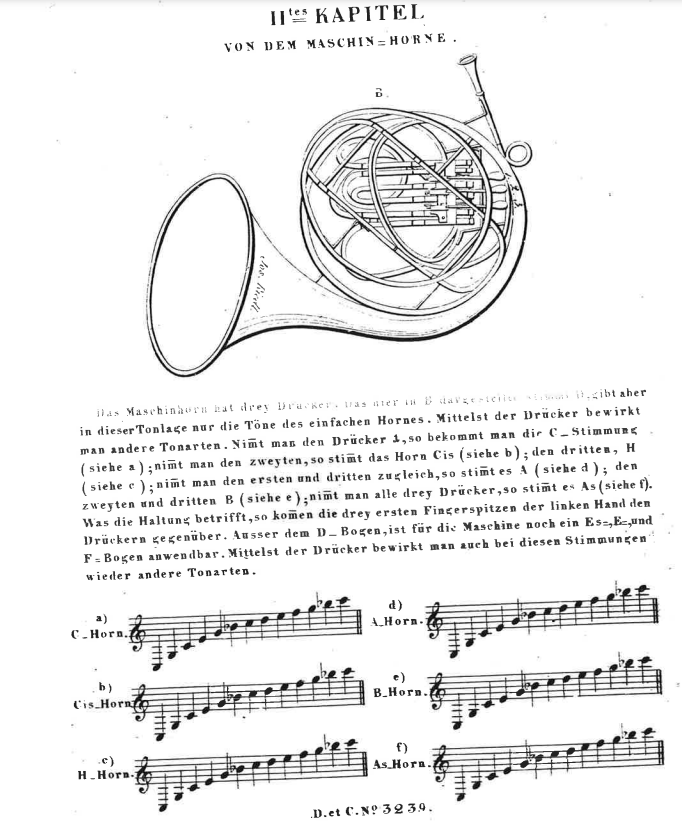

Andreas Nemetz has possibly the first treatise which mentions the Maschin-Horn. Although there is no written information about what he or other contemporaries thought about the instrument, and there is not too much information how people really used it, we can still seek out a bit of interesting knowledge which enlightens us about the use of the instrument in 1829. One of these is the fact that they already used the three valved version according to the pictures, they possibly used the valves as a crooking device: ‘...One can control other tonalities with the use of the valves. If one takes the 1st valve, then he gets in C…’; and the instrument still had crooks, which could change the ground tonality of the instrument. Beside the short explanation the book includes a fingering chart and a couple of small exercises.

Henri Kling (1842-1918) was born in Paris, but he grew up and studied in Germany, but Geneva was the place where he spent the most time during his career, as professor of solfége and horn.5 6 Among the horn players he is not known because of his Horn-Schule, but for his piano reductions, and editions for Mozart’s horn concertos. Many of the hornists do not agree with his version, especially the ones who play historically informed, but no one can deprive him from his good ideas and points of view as a teacher, which he also wrote down in his treatise. Nor the fact that this work is one of the most authentically descriptions of how the top musicians used the valve horn at this important period.

Like other leading hornists from this time, he also advises to start with the natural horn, ‘in order to obtain a thorough mastery in horn playing’, and for the purpose of acquiring the true quality of tone characteristic of the instrument…’ This completely agrees with the French professor’s and other important horn player’s opinion, that the natural horn’s sound (colour) is the real and only horn sound, and it is important to preserve its character, and the everyone should avoid to treat the instrument as it were Cornet à pistons or a trombone, as Kling says. To give a tool for other teachers and students, the treatise begins with explanation and studies for the natural horn and he introduces just later the valve horn. It is also important to notice that the majority of the method is playable on the natural horn,7 and only a few parts and etudes are meant for the valve horn, like the ‘Six grand Préludes’.

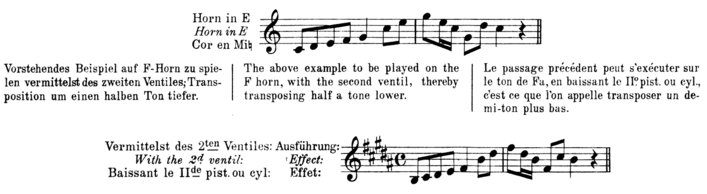

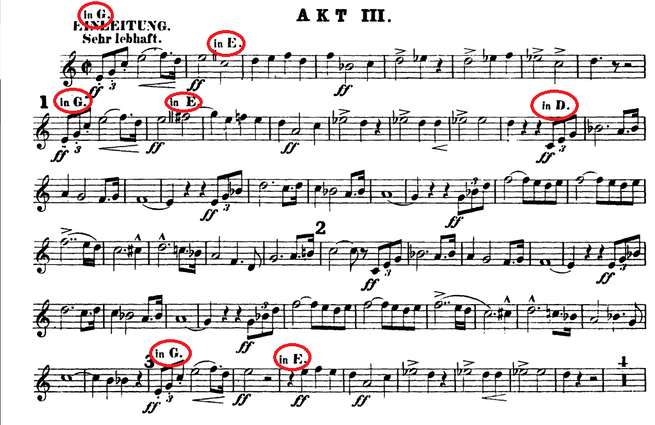

In the chapter ‘Practical Hints to the Orchestral Artist’, beside a lot of useful advice, he gives special attention to the transposition. As the valve horn started to be the common instrument, the musicians also started to change the crooks less frequently, and the F crook became the general tune for horn, since this key is in the middle of all the tunings (from Bb basso to C alto)and on this one is it the most possible to have an overall good sound and playability. This absolutely understandable trend also caused many hornists to assert that the use of the crooks in connection with the Ventilhorn should be discontinued [...] since everything could be transposed on the F-horn [...] I advise the employment of the G, the A , and the high Bb crooks whenever these are indicated by the composer.8

Actually, Kling’s words and opinion shows what will happen in the future to do less crook changes and what was the intention behind developing the modern double horn, and why and how the modern horn playing technique was established.

Here Oscar Franz says that it is getting to be usual, that the hornists use one particularly crook which will not be changed during the entire piece, and the valve horn was not used as a hand horn with rapid crooking device, and they completely abandoned to use the hand technique, except when the composer asks for a stopped sound. In the following, he says that despite of the different character of the different crooks, if someone plays well the horn, it will not be noticed by the audience, that the horn player took a ‘wrong’ crook:

‘It cannot be denied that the tone in certain passages will sound better when executed in the original pitch, [...] the tone of the E flat and C horn sounds fuller than in F. However, as long as a passage is executed perfectly, little notice will be taken whether or not it has been transposed.’

However, he also made it clear that there are differences in the tone colour of the different crooks, and it is very important for us horn players to notice the asked crook of the piece in order to find the best character and sound for the piece. For instance, when one plays a part in low B-flat horn, like in Gran Partita by W.A.Mozart or the 4th movement from Beethoven’s fifth symphony (Horn in C basso) on the F, or even on the Bb horn, he should pay attention that the horn does not have a bright and brilliant sound, more a deep, round, and mellow sound. But it is true in the other way around too, the horns in Beethoven’s seventh symphony (Horn in A) or at the end of Joseph Haydn’s Jahreszeiten (Horn in C alto) should sound more like a trumpet instead of a hunting horn.

In contrast to this, he advises to change the crook, if the composition requires one of the ‘high’-horns, like G, A, B alto horn:

‘As the tone of the higher-pitched Horns invariably sounds brighter and clearer, the following examples should be played in the original pitch.’

All these ideas, comments, and suggestions show in the same direction. These musicians found it important to keep the diversity of the notes, the character of the instrument, but use and produce them on an instrument, which has actually every note as open notes, but being aware and carefully, because it can sound very monotone and boring sound, which is of course, not the aim of a performer, except special occasions.

The other big question of horn playing, transposing, is answered in my opinion. They say that it is not necessary to change the crooks every time, since it is not audible for the audition, whether one plays a piece on the F or in the Eb crook, but it can matter if there is a fourth or bigger difference between the required crooks, and especially the high crooks should be used in order to have the right sound character, and a better efficiency. This last observation fits also perfectly in the history of the horn’s development. Why the shorter Bb and the longer F crooks are mixed in the modern double horn.

‘Although horn players now use almost exclusively the horns in E, F, high A and high Bb (incidentally, it requires practice to change the bright and sharp tone of the horn in Bb into the soft and noble timbre of the horn in F) [...] Except for the above stated difference in softness between the horns in F and high Bb, all the other differences in timbre between the various valve horns are merely illusory. This is why many horns in different keys are no longer used. Generally, the players of the first and third horns use the horn in high Bb for almost all pieces in flat keys and the horn in high A for all pieces in sharp keys. The players of the second and fourth horns use horns in E and F.’ 9

Strauss saw in his surroundings that horn players used mainly two different crooks. The first and third, so high hornists, the Bb and A, and the second and fourth, low hornists, the F and E. One of these crooks was used for the tonalites with flats, the other one for tonalities with sharps. This change is the same as what clarinet players do too. The choice of the high or lower pitched crooks depends on the register where the hornist usually plays. Because the higher, and shorter crooks work better, and provide a better and more secure accuracy in the upper register, the hornists who were solo hornists or played the third part, chose this one. Actually, Franz Strauss was possibly the first hornist who started to constantly use the horn in Bb. 10 11 For the low horn players it was not so important to have a tool which gives them bigger sureness in the upper register, and they do not play so much in that register. But it was important to have a nice, mellow, warm, and round sound in the lower octaves, which can support the high hornists, and we must remind ourselves that the F-horn has more notes in the low register than the Bb-horn.

‘Horn parts as a rule, are written without any key-signature at the Clef, owing to the various crooks or tuning slides employed in connection with the instrument, [...] In modern compositions however, it is of frequent occurrence that no time is left for the player to change his crook and oft-times the key changes without the slightest pause; [...] it is necessary that the pupil become proficient in ‘transposing’[...]’12

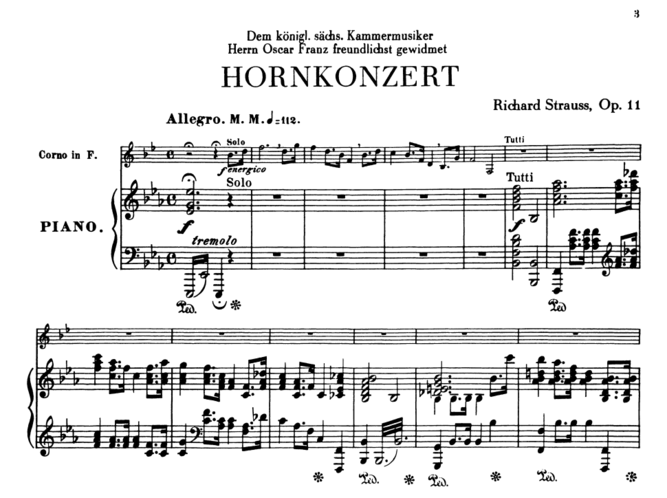

The person whom Richard Strauss dedicated his Nr.1 Horn Concerto in Eb-major op.11 was Oscar Franz (1843-1886), which proves that he was one of the most important and prominent persons in the history of the horn, though he is not the most well-known hornist today. He spent his active years in Dresden, where he played in the Dresden Staatskapelle and he taught at the Dresden Conservatory as well. The Grosse theoretisch-praktische Waldhorn-Schule is his major work which, similarly to Kling’s book, has two important chapters: The Stopped Horn and Transposition. The first one gives us the same advice that it is worth it to start with the natural horn and change to the valve horn just when we had got to know the true character and personality of the (natural) horn.

The second chapter shows us how and why the hornists and composers started to reduce the number of the used crooks, and how the Bb/F horn evolved:

It is clear that on the F horn the natural tones are getting closer, sometimes too close in the register where these high-horns sound the best, therefore it is useful to pick a shorter crook, which has the best playing range in the asked register. Oscar Franz’s opinion and as we will see, Richard Strauss’ too, explain to us why the Bb/F or F/Bb is the most common tuning on the horn nowadays.

Finally, I would like to mention Franz Strauss (1822-1905), and his son Richard Strauss (1864-1949). If we are interested in the topic of what kind of technique was used in the second half of the 19th century, then it is not possible to avoid the resources that they left behind. Their compositions, etude books, and theoretical works give us a great overview of how the role of the horn changed at that time, how the musicians adapted to the new tool, and how the modern playing technique evolved.

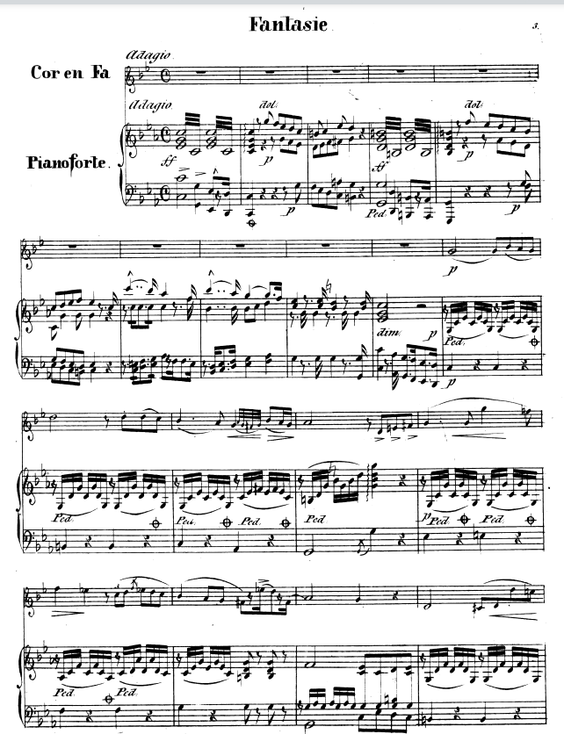

Though Franz Strauss did not write any treatise or Hornschule, he composed two concertos for horn and orchestra, some pieces for horn and piano, and a couple of exercises, both for Ventilhorn and for Waldhorn. I also think and in another research I could prove that he wrote one of his first works for the natural horn. The Fantasie op.2 is completely playable on the old instrument, though it has some tricky spots, but at these places he uses them as perfect effects that support the musical message. The exercise collection and this piece mean that he played first on the hand horn, and it was important for him to be master of it too.