The project · Ensemble Studies · BLY · The Hands. The Double. · Seminars

•

Artistic work · Can I both hear and see music? · Composing through my body

Composer Henrik Hellstenius on creating the choreographic piano work “The Hands. The Double” in collaboration with pianist Ellen Ugelvik and choreographer Kristin Ryg Helgebostad.

The idea of exploring an extended or expanded material for composition and performance comes from my own experiences working as a composer and improvising musician in collaboration with dancers and actors. But also through meeting works by composers such as Maurizio Kagel, Carola Bauckholt, Manos Tsangaris, Heiner Goebbels and Georges Aperghis – to mention a few of the central ones. In works like Repertoar by Maurizio Kagel, Recitations by Georges Aperghis, Winzig by Manos Tsangaris, Schwartz auf Weiss by Heiner Goebbels and In gewohnter Umgebung III by Carola Bauckholt, the material spans from compositions for boiling teapots, gibberish language, objects of different kinds, movement, video, lightning and much more. These are extended materials for musical compositions, created from principles, methods, ideas and traditions from musical composition, and performance.

The Extended Composition project has its origin in this experience of an expanded musical field, and in the work with The Hands. The Double I wanted to combine movements, language and organized sounds. After some initial workshops held together with pianist Ellen Ugelvik and cellist/composer Tanja Orning, experimenting with text, musical sounds and movements in the project, Ellen Ugelvik and I continued the work We let language and text rest, and focused on the exploration of movements and space as musical material. In the finished version of The Hands. The Double, we included language as a material in the last part of the piece, but our curiosity was centered around movement.

Material and instrument

In his famous article Music in the Expanded Field, Marko Ciciliani writes about how not only the material has changed in the expanded field of art music, but also the instruments. He points to the composer Helmut Lachenmann's reflections that composing also means building new instruments. In this context he refers to how Lachenmann explores new sounds produced by traditional instruments, and by combining all these new ways of sound production, Lachenmann creates new “instruments” . Cicilliani points to the fact that for younger composers working in the expanded field, it is common to compose for non-traditional instruments. He quotes the composer Stefan Prins from his article Componeren Vandaag: Luft von diesem Planeten:

Today, this metaphorical instrument no longer merely consists of an orchestra, a piano, saxophone or tape recorder, but includes laptops, game-controllers, motion sensors, webcams, video-projectors, midi- keyboards, internet protocols, search algorithms ... This novel meta-instrument obeys a different kind of logic; it creates different fields of tension; it has different possibilities and different implications; it creates different material and asks new questions. It is urgently in need of other modes of presentation and requests other approaches by composers. (Cicilliani p. 25)

In our project, this new instrument was the body of Ellen Ugelvik, and the material was her movements. By choosing Ellen´s body and movements as instrument and material we entered into a new field of artistic creation as composers and performers. A field were we lacked skills and experience one would normally possess when creating choreographic works. Even though both Me and Uglevik have worked with dancers and choreographers on multiple occasions over a number of years, the task of developing a work based on movements was new to us, and so we were amateurs in movements but capable in making and performing music. To be an amateur in a field has its advantages. One may approach the field in a new and different way. But, as Cicilliani writes, not knowing a field´s history, material, and interconnections also has its challenges:

Certain elements which might be new in one discipline may already have been dealt with decades ago in another discipline, and therefore be unsuitable in their expressive potential. At times this can be quite disillusioning. For example, one might be excited at finding a clever way to turn pixel information into sound synthesis, only to discover that the same idea was already realized by experimental film makers in the 1940s, who were drawing their sound onto film manually. (Ciciliani p.27)

To meet this challenge I will insist on a strong musical foundation in the work, making everything into music, or from music. By conceptualizing the movements as musical material together with the sounding material, I might contribute to the expanded field of music with something that is different from other intermedial artworks with movements and organized sound. We do not create choreography in The Hands. The Double, rather a “choreographed pianowork”. We musicalize movements, and compose with them into a musical/choreographic form. Based on discussions along these lines of material and form we decided on a “stage” for the piece; the space between two instruments, a piano and a keyboard. In this space, Ellen´s movements are integrated with her role as performer of the two instruments.

All is music

To me it is important that an intermedial work containing organized sound or music must have a strong musical core. I have over a long period of time been frustrated by intermedial works by musicians and composers where the sound, and the composition of sound, has been flat and uninspired, weakened by the stronger presence of other artistic elements, such as video, movements, lights, objects, or text. In numerous intermedial artistic projects, I have observed that musicians and composers have become second rate visual or video artists, as Cicilliani reflects on in his article, presenting works with poor organized sound/music. I am fully aware that the organized sound in an intermedial, extended work, consisting of several artistic outputs, will have to be balanced with the overall density of medias and information. Intermedial works demand a different approach to sound and music than works where the music is the major language. But composers like Jennifer Walshe, Manos Tsangaris, Trond Reinholdtsen and Carola Bauckholt have shown us that it is possible to have both a strong musical side and a rich visual/linguistic side to an intermedial work. To me, this has always been the most stimulating approach. When musicians and composers take their position seriously and develop new artistic expressions based on their competence as musicians, utilizing the thinking, practices, tradition, and techniques from musical composition in a new field of art. I would argue that the key to the success and excitement around the works of a composer as Simon Steen Andersen lies in his unique musical approach to creating intermedial works. Works that could not be done by others than musicians and composers, because they are based in a profound musical artistic practice. In my view Steen Andersen has contributed both to the visual field as well as the musical field.

With the noticeable exceptions of works by pioneering composers such as John Cage, Maurizio Kagel and Nam June Paik, it appears that the field of art music required more time to extend its material of composition to include movement, space, and visual expressions than the fields of visual art, dance, and theatre. Artists with their origin in visual arts began to explore the theatrical space through what we now label as performance art as early as with Cabaret Voltaire and the Futurists in the beginning of the twentieth century. However, musicians and composers striving to create their own intermedial works need not copy other artforms´ explorations and expansion of material. Rather, they should begin from what is unique and different in the tradition of musical composition and performance when extending the material and practice. Extending and expanding the material but still defining it as music.

In the given context, however, I would like to focus on music as a practice that allows the inclusion of non-sonic elements, rather than music as an object that has to be defined, in order to describe something that I consider a relatively young development and which I will take the liberty of calling “Music in the Expanded Field.” (Ciciliani p.24)

Limitations

Following this argument, Ellen Ugelvik and I aimed to preserve a strong musical side to the work, even when entering into the new realm of composing and performing with movements and space. We decided that our sources of sound was to be the piano and a keyboard playing samples and sound files. We then made two decisions, creating a framework for our explorations. The first was to limit ourselves to playing on the keys of the piano and the keyboard, excluding all playing inside the piano. The second decision, and limitation, was concerning space. We decided on the previously mentioned “stage” for our piece, the space between the two instruments. This framed our explorations and work with movements, leading us intensive work on movements in the hands, arms, torso, and head. The decision to ignore the larger space surrounding the instruments also meant omitting any work with larger movements and displacements.

Before deciding this last limitation, we held a series of workshops with the performer and dancer Shila Anaraki, who challenged us to explore possible combinations and relations between the piano, the keyboard and the body. Though an unpretentious and playful approach, all the tree of us, Ellen, Shila, and me, took turns in improvising movements and sounds. In the conversations between Ellen and me following these workshops, we discussed the potential challenges Ellen would face in filling a larger space with movements. We feared that this would force comparisons between Ellen's skills as a performer of movements, with those of a trained dancer. In hindsight, knowing how far Ellen came in the work with movements by the end of the process, how she managed to acquire and develop her skills as a moving performer, filling movements with intention and content, I think we could have chosen different spatial limitations.

Ellen's body as instrument

In the continuation of these and several other workshops we started to address the fact that it was Ellen's body that was the instrument of the piece. It was through her movements and musical performance that the work came alive. Since Ellen is not a trained dancer, the movements had to fit her body, and feel right to her. She had different limitations than a trained dancer normally would work with, and the movements had to facilitate Ellen's ability to perform on the instruments.

The advantage of an artistic research project like Extended Composition, compared to a music production for a festival or concert, is the period of time one is afforded to work it. Collectively, we both had time to explore and create movements, but specifically, it afforded Ellen the time to, step by step, develop her abilities as a moving performer alongside the creation of the piece. In the video documentation following this article, one sees clearly the different steps in Ellen´s development, from the start of the work to the finished piece. She improved both her range of movement and her ability to memorize long sequences of complex movements. As already mentioned above, if we had known at the onset of the project what we know now, we could have defined a larger space for Ellen to move in from the beginning. On the other hand, a larger space, and bigger movements still make other demands on the moving body. In my opinion our choice of limitations gave a focus to the movements and connected them to the musical sound.

Ellen is a pianist, and her body is trained to be a music-making body. The author Paul Craenen writes about in what way this music-making body is present in musical performances, and what different functions of the body emerge when used as a material for composition. He is concerned with the fact that the body already has a function in the creation of music, as it is essential to most music-making. This already established physicality in music must be acknowledged when one wants to use the music-producing body as a compositional material.

The music-making body differs from the theatrical body in the specific relationship it has with an instrument. It does not appear on stage as a body exhibiting itself, but as a trained body making a musical effort, a body directed towards an instrument. (Craenen p. 204)

Craenen argues that when the body liberates itself to gain an independent function in a musical situation, and such exposes itself as material for composition, it loses its “home” in the medium of music.

It needs to reorient itself seeking out a new destination. One possible orientation may be the expression of the crisis in which it finds itself – or to be more precise, the expression of the process by which it becomes audible. Such expression requires a self-reflective stance. The music-making body that wishes to attract attention to itself needs to create a critical distance that enables or stages the experience of making itself heard. (Craenen p. 204)

In the first part of our work The Hands. The Double, we address Craenens notion of a crises. The piece commences with a pianist in a traditional position for the music-producing body before gradually transforming into a theatrical body. In fact, the whole first part can be seen as a process where the body is seeking to liberate itself, and become material on its own terms. Simultaneously as the body gradually liberates itself by Ellen letting her upper body sink towards the keys of the piano, it establishes an opposition to being a music-producing body in the traditional fixed posture by the piano. Ellen´s body goes from being a music-producing body to become an independent body in itself producing meaning and signs.

The difficult choice of movements

After our choices of limitations was made, we continued to play with movements we wanted to add into the compositional process. This led to a discussion on what constitutes a good movement – a movement we can build a continuation from. How to choose, discuss, and evaluate what is good and not good in a movement? What criteria’s to use, and what language was available to us that would enable us to communicate the qualities and problems with a movement as a material for composition?

Since we did not have the training or the tools dancers and choreographers possess, we had to formulate ourselves via metaphors, and often musical metaphors. We evaluated the movements as gestures, rhythms, forms, and shapes. In this work, a lot of interesting questions came up. Questions and issues that seldom is touched on in the work with musical works. Some movements can be perceived as more abstract, but a lot of movements create associations towards actions, mental states, and cultural signs. These signs and associations create intertextuality we had to be sensible of. From the combination of movements and music that is performed new possible meanings emerge. The combination produces a polyphony of signs; visual signs, phycological signs, musical signs etc. The material is not neutral, and a lot of our discussions were efforts at disentangling what we understood to be the significance of the different movements, what type of signs they produced, and what kind of meanings the signs could produce.

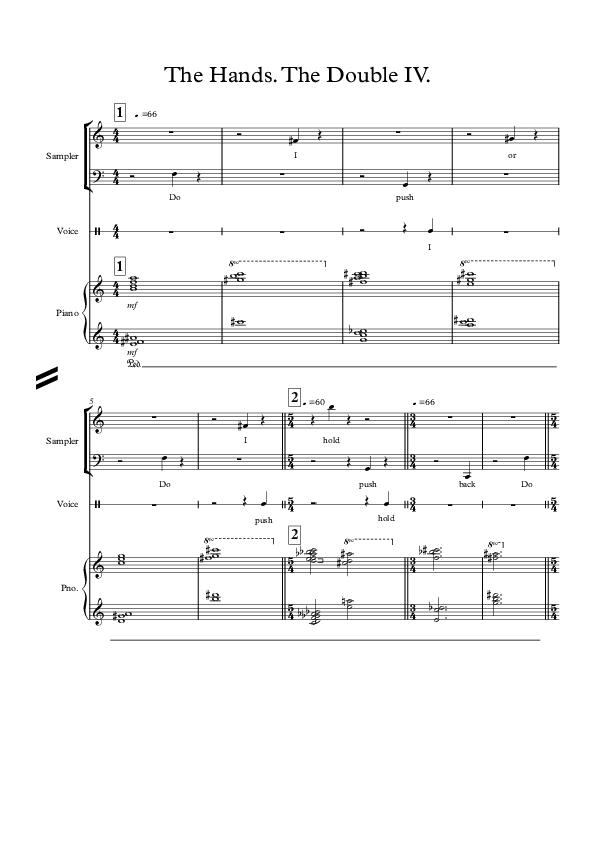

Notation of movements

In an attempt to confine this polyphony of signs, and create movements that were unambiguously and distinctly a material in a compositional system, I experimented with writing scores for both movements and sound. In one of these scores a simple rhythmical structure is used to link movements and sound. In the notation the movements are alternately linked to playing on the two instruments, and being independent and abstract movements with hands and arms. The movements were taken from a piece where choreographer Kristin Ryg Helgebostad and I worked with a choir, and where the possible movements were limited by the singers always standing behind note stands.

The movements in this sketch are easily read as part of a musical practice. Partly since it is clearly an element in a rhythmical structure, but also because the fact that Ellen is reading a score is important for how and in what way the audience interpret the movements. They understand that the movements are notated, and part of a musical system. I found this to be an interesting way to continue our work but Ellen problematized both the method and the movements in themselves. Her misgivings were twofold. Firstly, Ellen was not fond of the specific movements we were working with. On a deeper level, she was opposed this way of working. She found it to be too similar to the traditional roles inhabited by composers and musicians. Roles in which where the composer produces a score and the musician executes it, while the composer is watching and listening. This was contrary to our talks in the beginning of the process, to challenge these traditional roles we normally inhabit in music life. Unwittingly, I had proposed a form of work with traditional fixed roles in which I created the score, Ellen studied it, and I was assessing the result from the outside, commenting on it. This led to a series of discussions between the two of us, but also in the larger project group, on roles; both how to define them and how to challenge them. In the following we did challenge the roles, and it is obvious to me now, that the resulting piece The Hands. The Double, would not happened had we not. However, when we were finalizing the process with the piece, preparing for the premier, we did resume our traditional roles. Something we found necessary in order to take the last steps, practicing for and producing the piece at a concert.

«Rotation» as method

To escape our roles and traditional division of responsibilities, we developed a strikingly simple method. The method came out of our continuous work where we started to switch between trying out movements and watching the other doing the same. Essentially, this is a method of co-creation, providing, at different steps in the process, a working method that enables participation and that affords everybody a decisive say in the evaluation and decisions being made throughout the creation of the piece. In theatre, the term devised theatre denotes new methods of collective work on stage.

Devised theatre – frequently called collective creation – is a method of theatre-making in which the script or (if it is a predominantly physical work) performance score originates from collaborative, often improvisatory work by a performing ensemble. The ensemble is typically made up of actors, but other categories of theatre practitioner may also be central to this process of generative collaboration, such as visual artists, composers, and choreographers; indeed, in many instances, the contributions of collaborating artists may transcend professional specialization. (Wikipedia)

The devising model is old in artistic work in theatre and dance, but has not been as common in art music. Even in the period of musical modernism and avant-garde from 1945, composers and musicians maintained the old separation between themselves. Even today, many composers and musicians, in what Cicilliani defines as the Expanded field of Music, uphold in varying degrees the traditional roles.

However, our simple «rotation-method», in which we switched roles as executer of movements/sounds and as viewer/listener, broke with the traditional roles of composer/musician in the early stages of the process. The “rotation” between performing and observing/listening enabled us to develop movements together in a new way. Both would take the initiative to integrate new movements, and both would evaluate the results, judging if the movement “had something” that interested us, how it could be developed, how it could be changed, and if it produced strong signs to something outside its mere qualities as movement, psychological, or cultural signs.

Movements as signs

Fresh to composing with movements we often experienced that this was far from a neutral material. Time and again, we ended up discussing what signs a particular movement conveyed. We often left a movement if it was too much of a signifier of a phycological state, a cultural sign, or a personal gesture. We discovered that some movements were read very differently when performed by a male or a female. Movements connected to the chest or the stomach radiated different signs when I was doing them, than when Ellen was doing the same movement. Our intention was to work with as neutral movements as possible, well aware that nothing is really semiotically neutral in its strictest sense. As a result, we had to discard a lot of our suggestions for movements and gestures. Our experience with movements being more complex to work with, is underlined by Cicilliani, who claims that there are three important factors to be aware of in the expanded field. While post-war modernism introduced the de-construction and re-construction of music´s most important parametrical components – pitch, amplitude, rhythm, and timbre – the new expanded field that composes with visuality, text, video, objects, light and space, meets new and different perceptual challenges. Cicilliani summarizes these challenges as intertextuality, physicality and modes of listening/economy of attention.

More recently, I have observed that new sets of criteria have gained importance which approach sound phenomena in their entirety and full complexity, and that cannot be grasped with the parametric decomposition of sound. The importance of parameters is therefore fading, while new objectives gain in relevance. This can clearly be seen with composers working in the expanded field, but is in no way restricted to them. While it would be impossible to examine all of those criteria, I would like to discuss three that also have special relevance in the expanded field. These are:

– intertextuality

– physicality

– modes of listening/economy of attention.

(Ciciliani p. 29)

The Hands. The Double is, to a large extent, about physicality. Pure conceptual works might produce a stronger intertextuality than a work like ours, consisting of movements and musical sound, but it is also our experience that even simple movements create connections of meaning to the world outside the realm of the piece itself. Even if what we see on stage is only a person that moves between a piano and a keyboard, the signs and meanings that are created from this are many and diverse. Some examples from the workshops Ellen and I had exemplified this. In our workshops, I produced some movements that Ellen reacted to, for instance putting my hands in front of my face, covering it, or resting my head in my hands while looking at the audience. Ellen interpreted these movements as phycological signs and meanings that drew the attention in directions we did not want to pursue. Without being conscious of this, I created an illusion of a state of mind rather than movements that communicated in its energy, direction, and compositional development.

A polyphony of signs and meanings

All expressions can be read and understood as signs like in the fundamental Saussurian model: 1. Signifier – material, and 2. Signified – concept of meaning . Or like in Pierce's three part model:

- Icon – meaning based on visual resemblance, or similar sensory perception

- index – meaning based on causal relations

- Symbol – meaning based on conventions.

… if the constraints of successful signification require that the sign reflect qualitative features of the object, then the sign is an icon. If the constraints of successful signification require that the sign utilize some existential or physical connection between it and its object, then the sign is an index. And finally, if successful signification of the object requires that the sign utilize some convention, habit, or social rule or law that connects it with its object, then the sign is a symbol.

(Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

In my improvisations where I laid my head in my hands, Ellen saw something that created meaning based on a visual resemblance between this posture and the posture of a man in despair. An iconic resemblance to a state of mind that Ellen would have seen depicted in images, movies, and theater numerous times, and maybe also in real life. My intention was not to communicate these signs, rather, I wanted to investigate the movement in itself.

Without going into semiotics in detail, I experience that by working with this extended material for composition and performance, we entered fields of intertextuality where our material pointed out of the work itself. Making them into agents in other fields of expression than composition for movements and musical sounds. Visuality and the presence of a moving body ignites a number of interpretations and associations pointing to possible meanings far outside our work. Body and language is what we use to communicate and read signs, in all its complexity and subtility. To me, working practically in the field of art but with a basic training and practice in music, it is has been important to expand my understanding of what possible signs can emerge from a material, and how could it be interpreted. A member of the audience at the premier of The Hands. The Double told me after the concert that this piece was obviously about “the frustrations of a middle aged women”. For this audience member the collections of signs and meanings coming from watching and listening to the piece was boiled down to a phycological/social state. This hints at the complexity one is confronted with creating works in this expanded field. In short all layers of signs in the polyphony of signs, emerging from a piece like this are effecting other layers. It arises an intertextuality crossing the medias in the piece, what John Fiske defines as horizontal intertextuality, in contrast to a mere vertical intertextuality, where meaning is produced inside a media.

I understand the experience of the polyphony of signs to a large extend to being individual. Based on individual experiences, interpretations and cultural references. I can imagine that all layers in a intermedial composition radiates signs to be interpreted in different ways by different people, and that they connect to other layers. Making up a spiderweb of possible relations and meanings between the different systems of signs.

What Ellen Ugelvik and I judged to be something relatively abstract, created from musical/compositional principles could thus be interpreted as a concrete phycological state of mind – not as a play with organized movements and organized sounds. Some audiences will more easily read phycological signs out of visual/bodily actions, and so the compositional aspect of the movements and sounds might escape them. A parallel is how language has a tendency to be the strongest layer of signs in a multi-layered composition that includes spoken words.

Modes of listening

An important aspect of musical works in the expanded field, is how one listens to a piece where there are more than the sound that creates meaning. Michel Chion has defined three modes of listening: Causal listenening, semantic listening and reduced listening. Causal listening is the most primary mode, in which the listener tries to identify objects, humans and events. Semantic listening is the understanding of language in its many forms; as sound or visual signs. Reduced listening is a concept Chion borrows from the French composers and researcher Pierre Schaffer. It covers what we do when we listen with intent and concentration to organized sounds, as in the form of music. We put the rest of the world around us in “parenthesis”, listening only to the sounds without focusing on the sources or surroundings of the sounds.

Pierre Schaeffer gave the name reduced listening to the listening mode that focuses on the traits of the sound itself, independent of its cause and of its meaning. Reduced listening takes the sound – verbal, played on instrument, noises or whatever – as itself the object to be observed instead of as a vehicle for something else. (Chion: Audio -Vision p. 29)

But how do we listen to a piece based on an extended material where it is not only the sound that creates the “music”? It could be movements in rhythmical polyphony with the sound, or language, meaningful as both semantics and sounds in a larger web. It could be objects that produces sound, but also moves or creates some kind of spatial effect that plays into a macro rhythm together with other elements. It could be video or lights that rise and falls in intensity as crescendos or decrescendo in sound.

How do we “hear” all this, when only parts of the totality of expressions in such a musical/compositional structure is sound? There are two emerging concepts that might help explain this mode of listening; aesthetic listening/contextual listening. I understand the two concepts to be more or less interchangeable as they both delineate modes of listening where the listener identifies that there are more elements than the mere sound that constitutes the musical code. These elements can be language, everyday sounds, objects, movements, light, video, and more. An important question is to what extent the audience is capable and informed about this type of listening. Can an ordinary audience integrate movements as a part of the musical code, or do one separate what one see and what one hears? And even further; does an extended composition prepare for an extended aesthetic experience? My friend and colleague, the composer Edvin Østergaard emailed me after the premier of The Hands. The Double, raising this question.

If the goal of your project is to create “a composition where sound and movements are equal parts of a polyphony”, I ask myself how this multi-layered composition – sound and movements is perceived. It is maybe not so that an «extended» composition process automatically create an extended aesthetic experience?

(Edvin Østergaard; personal email to Henrik Hellstenius 23.09.2021)

The making of The Hands. The Double

In the following I will try to circle in present the process that followed our first workshops and the establishment of the “rotation-model”, our devising model, until the finalization of the piece preceding the premiered at the Ultima festival in September 2021. I will try to describe the different steps of our work, and how we together developed material for movements and sound. How we discussed and assessed the work as it was in the making. The final piece consists of four part, where the first, the fourth, and the start of the second are the clearest sections. The third part unfolds as a development and intensification of the material introduced in the second part.

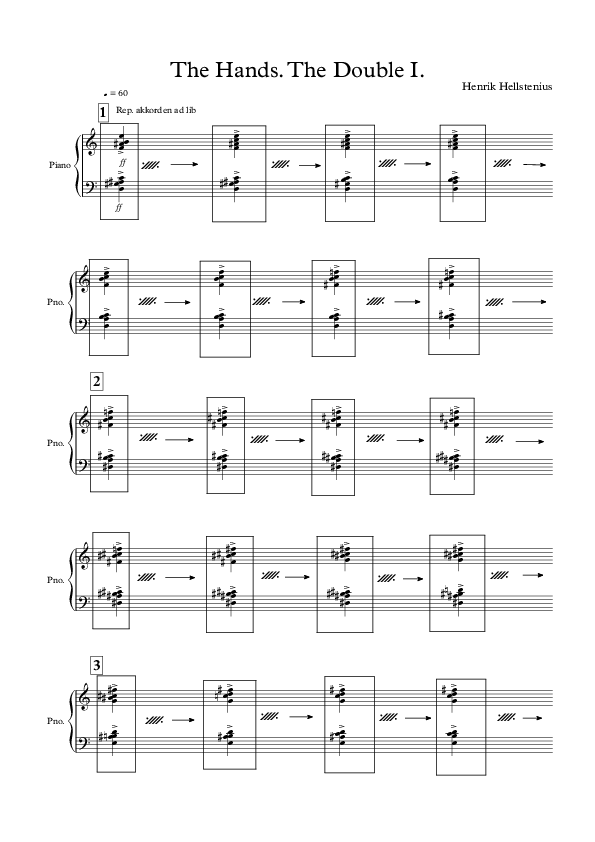

The first part consists of a series of repeated chords, played by Ellen at the piano. Her body transforms from being a conventional music-producing body at the beginning of the part, to gradually liberate itself, developing its own expression.

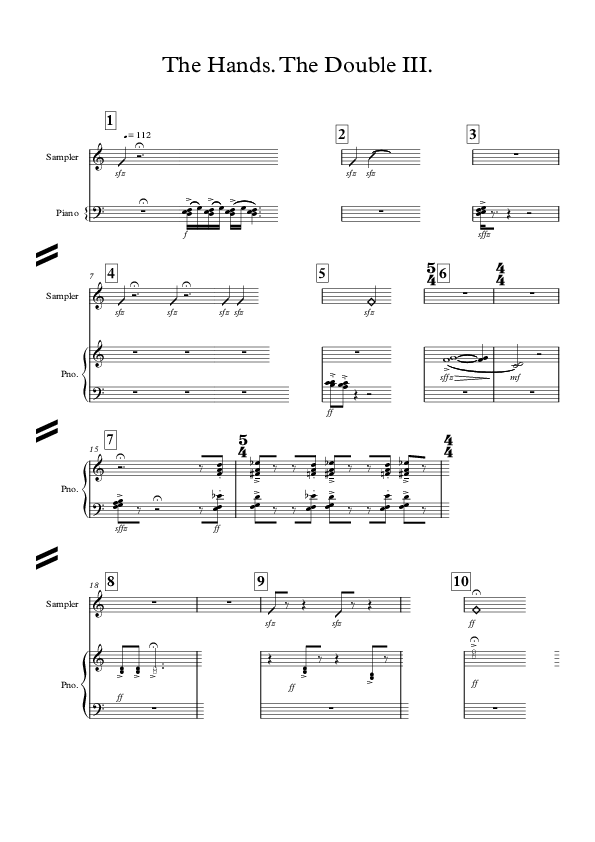

Part two focuses on smaller movements and develops a material done by hands, arms, head and the upper body. The sounds are piano clusters/chords, and samples of prepared piano.

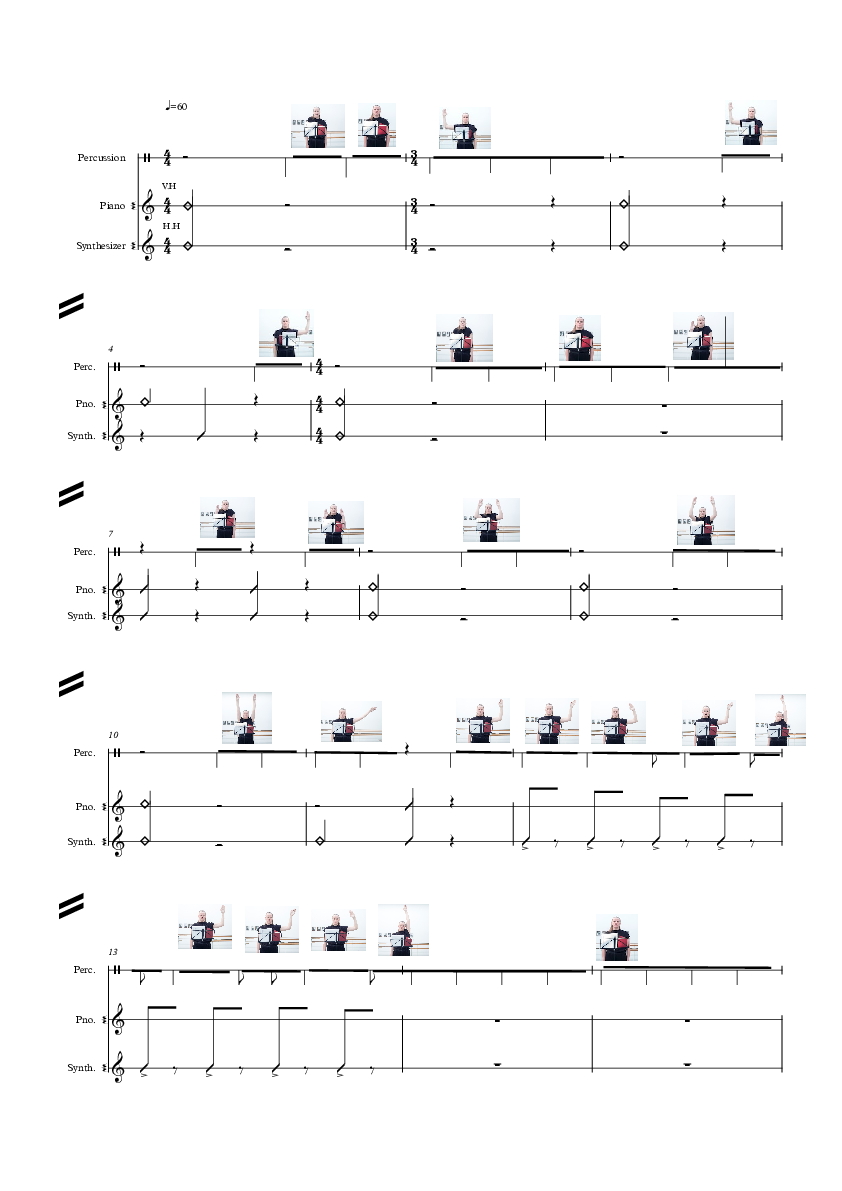

Part three develops the material from part two and stretches Ellen’s abilities as a performer of movements and music to a maximum. Here, the composition is at its most complex and dense, where the music and movements are composed tightly together and notated in both a traditional score and a video score,

Part four is based on a series of piano chords unfolding in circular sequences. Samples of Ellens voice, and Ellen speaking live together with the piano chords creates a rhythmical structure where chords and words rotate and develop in as spiral fashion. The movements in this part, a rotation of Ellens upper body to alternately play at the piano and at the keyboard, is more static and still than in the preceding parts.

Deciding on movements

The challenge we had at the end of 2019 and in the beginning of 2020, was how to choose what material to attach ourselves to and decide which movements had the potential to form the basis of longer sequences of movements. We tested out a wide range of different movements, but had difficulties in choosing a central material. We had also failed to create an interesting musical material though our “rotation-method” as our focus was more on movements than sound. I do think that many artists, like us, become engulfed in the new and extended material in the early stages of a process like ours. The material is new, and we do not control or comprehend how to manage it fully, so it demands almost our complete attention. We were in the process of learning a new medium/material and creating with it at the same time.

In an attempt to create a starting point for both movements and music, I made three sketches to movements/music, recording sound and video at a cottage north of Oslo in the midst of the pandemic. In many ways this broke the rules for our “rotation-model” and devising model, but the three sketches were made inside a frame we both had decided upon in advance, and inspired by much of the material for movements we had tested. The three sketches, I, II and III, became the starting point for the finished piece The Hands. The Double.

I.

For the first sketch, I wrote a series of chords for piano that develops from the first chord by simple chromatic movements of the pitches inside the chord, one by one. Every chord is repeated a certain number of times, before an alteration is done. The principle of chromatic development is taken from the famous movement “Farben” from Arnold Schonberg’s Five Pieces for Orchestra op. 16. The intention was that such a simple displacements of chords following the strict rule of chromatic movements for each of the pitches in the chord would make it simple to perform the chords from memory. This would then facilitate the necessary freedom to work with movements. We experienced very early that having to read scores made serious limitations on the movements we could work into the piece. It delineated both the possible direction of movements of the head and glance, and influenced the concentration and focus on the movements.

My original inspiration for the movements of this sketch was taken from a memory of a solo concert by jazz pianist Keith Jarrett. He was famous for moving and singing while playing, and, at a concert where Jarrett improvised a three part fugue, he bent and twisted over and under the keyboard of the grand piano while singing and playing this immensely complex improvised music. My version started in a sitting posture, playing the piano, gradually lowering my head and upper body towards the keys. Letting the head fall all the way down to the keys, then pushing the body backwards and upwards, ending in a standing position. This sketch was to become the model for the beginning of The Hands. The Double, out of which we developed a long sequence that started with Ellen sitting “normally” at the piano and then gradually falling all the way down, with the upper body and the head almost touching the keys. Ellen would then push out her right leg, and gradually rise to a standing position. This was to be done simultaneously with an intensification of the movements, that led to Ellen almost throwing herself towards the keys of the piano and the sampler.

II.

Sketch number two was inspired by movements Ellen and I already had tested out together, sitting between the two instruments with the body facing the audience. In my sketch, the intention was to create a series of simple bodily gestures and equivalent musical motifs that repeated itself in a pattern, while new gestures and motifs were added along the way. Some of the bodily gestures and musical gestures/motifs where linked together, like with the fist, the hand hanging down and the hand on the thigh. Other movements and musical motifs were more loosely connected.

In this sketch, it is also possible to trace the elements that develops into the second main part in The Hands. The Double but in following work many new elements where added and a lot that was originally in the sketch was dropped or changed. The most striking difference is that the sound/music became much simpler in the final version than in the sketch. We understood early on that the score I had written did not work with our development of movements. The need to see the keys meant loosing energy and attention on the bodily gestures. We therefore had to find a different solution for playing at the piano and the sampler. Concerning the movements, it was only the movements with the knee and the thigh that was taken further from the sketch to the finished part. In developing the movements in our “rotation-model”, it was clear that we did not agree on the movements with the fist and the hands in front of the face. We therefore removed those movements after discussions where Ellen reflected on their semiotic sides. Namely, that these kind of movements sent out cultural and psychological signs, different and stronger than the other movements. The two hand movements on the chest and the stomach were also left out. We discussed that these had very different connotations being performed by a woman than by a man. The removal of these movements were done by a wish to eliminate a vertical intertextuality and reduce the complexity in the polyphonic web of signs. I had not been aware of these issues when I worked with the sketches. The choices done as a result of our discussions were made to keep the language of the piece as “neutral” as possible, and reinforced the importance of our devising model.

III.

This third sketch was to be the starting point for the last part in The Hands. The Double. The focus was on a rhythmical play between a series of chords and a series of words. The text is performed partly through samples of Ellen’s voice and partly spoken live. In the sketch I toggle mechanically between chords and text, this was later developed to a more complex interplay between chords, samples voice and spoken words.

Two becomes three

The sketches I made was shared with Ellen and we took them as a starting point in the further work. They did contain more detailed suggestions to musical structures than we had worked with before and the movements were not scored as in the example 02.Mov1.score.

I imagine that representing the movements by video and not by score, enhanced a 1:1 relationship between the material in the sketches and the continuing work on movements. It also made it simpler when we asked choreographer and dancer Kristin Ryg Helgebostad to join the work. She joined our process first as an “outside eye”, sharing thoughts, commenting on how we worked, and suggesting possible directions and choices to make. But shortly Kristin started to improvise her own versions of our sketches and by that joined our devising model. The “rotation” now included three people sharing the responsibility of performing and commenting. After meetings with Kristin, Ellen and I continued in our workshops inspired by Kristin. We absorbed movements that Kristin had created, based on our material and added these new versions in our work.

Development towards finished work

Following our collaboration with Kristin we had concrete sketches for sound and movements and a new model for the development of our material. In the following, I will try to present in text and documentation videos how the process towards a finished piece was conducted by Kristin Ryg Helgebostad, Ellen Ugelvik, and myself. I find it important to present in detail the different steps of our development, in order to understand how a process like this takes place. It has been an important and instructive process which, obviously, was intimately linked to us three as individual artists and personalities, but I am convinced that elements in our process are transferable to other artists’ processes and works.

In the development of the four parts of The Hands. The Double, part one was based on sketch I, and part four on sketch III. Part two was based on sketch II, but ended up very different from the sketch. Part three was developed together with Kristin Ryg Helgebostad when she joined our “rotation-model”.

Part One

In the first part of the piece, we worked to stretch the opening where Ellen goes from an ordinary position as a pianist (“a music-producing body”), slouching all the way down, almost touching the keys with her forehead. Our focus was on this first, slow, development and how to get up in a standing position, that would trigger a massive energy of movements towards the piano and the sampler. Ellen proposed we worked with guitar pedals so she could manipulate the piano sound towards a distortion, parallel with the intensifying movements.

This resulted in a version we showed the project group in Extended Composition

As a result of discussions and feedback in the project group, we removed the pedals, since they took away the focus and the line in the movements. The process of distortion of the piano sound was in the following done by me in the program Abelton Live, via different processes of granulation, filtering and delay. This opened more possibilities for Ellen to move freely. In cooperation with Kristin, we worked to clarify and reinforce all movements in this part. A video from a workshop in June 2021 shows how Kristin and Ellen work together with the development of the movements.

Part Two

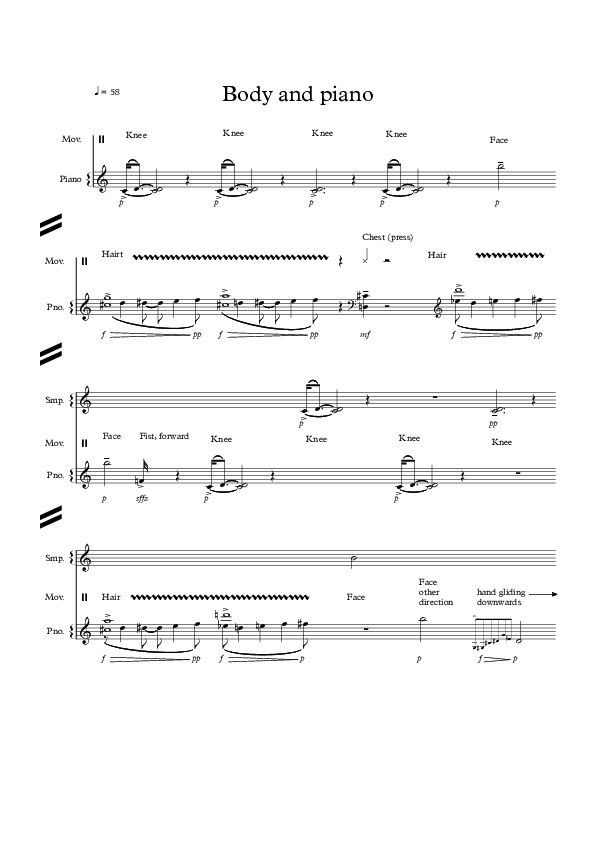

The development of part two originated in the sketch I made in March 2020. We removed the music and most of the movements from the sketch, focusing on the small movements with the hands around the knee, added descending and ascending movements in the upper body, explored twisting of the head and the upper body, as well as sideway falls of the upper body.

This was made into a form with the movements as “musical” motifs. My approach was to emphasize that both the rise and fall of the upper body, and the movements of the hands, are musical material. They are all gestures in time and in different tempos, pretty much like rhythmical figures. We worked with repetition, contrasts and development of the movements, just as we would do in a sounding context.

Kristin Ryg Helgebostad made improvised versions of the movements Ellen and I had created, showing us possibilities in this quit minimal material, and inside this limited space. By doing so, she helped us to expand the material and enrich the compositional work we did. Her skills as a dancer and choreographer made her able to envision new possibilities and expansions of the material we worked with in situations where Ellen and I would repeat what we already had done. In a series of improvisations Kristin and I did, we stretched our ideas both with movements, but also the musical sound. The improvisation in the following video shows how Kristin develops the material in part two, using the space around the piano.

Based on elements from this and similar improvisations, we worked out three different sections for part two. The first section has movements with the upper body and the head, playing dense chords on the piano and samples of prepared piano in the sampler. The second sections is a duo between the hands, exploring the knees and playing samples of e-bow on piano strings. The movements and the sound are almost mimicking each other, being similar gestures with the same start and end points. In the third section, Ellen stops playing, and sound files of pitches played by an e-bow on piano strings are folding themselves out. The movements are now disconnected from the sound and becomes more abstract forms with the hands, arms, and upper body. Gradually, the piano and samples are added.

I wrote a very simple “score” for this part where the movements and the playing on the instruments are just notated in short words. It is not notated what Ellen should play on the instruments, only what instrument and when. We wanted to focus on the movements as Ellen sits facing the audience and cannot see the keys on the instruments. We agreed on the density of the piano chords, just by where to play and how her hands should be formed, to create clusters or open chords. We also agreed on when to computer process the piano. For the sampler we agreed on when to play, what sounds to use for the different movements, and which register to use, not the specific pitches.

Part Three

The third part is by far the most complex of the four parts. Both in the movements themselves but also in the relationship between the musical sounds and the movements. It was developed in a different way than the others, as it is based on an improvisation Kristin Ryg Helgebostad and I did during a workshop. Kristin’s improvisation departed from the movements we already had developed in the second part, but she developed them further. Creating rapid shifting movements, using more or less her whole body, still sitting in between the two instruments. In this improvisation Ellen and I experienced that Kristin added an energy to the piece that we felt were lacking. We needed a part that were more complex and intense than the others, both in the movements and the sounds. The form and development of the material in Kristin’s improvisation was so strong that we decided to base the whole of part three on it, since Kristin developed from our movements into new movements. She created a strong and convincing formal development of our material, and included musical elements. The intensity and the power in the movements also created a formal link to the first part of the piece.

In June 2021, when this improvisation was made, we knew that the premier of the piece was to be in September. It was therefore about time to decide upon the finished material and parts and for Ellen to initiate her process of learning and rehearsing the piece. We decided that part three was to be based on Kristin and my improvisations. I created two types of scores for Ellen. One ordinary score for the piano and sampler part, and one video score for the movements. The video score was made in such a way that I divided the improvisation into smaller numbered sections, and made both slow motion clips as well as in real time for Ellen to rehearse together with the musical score.

The rehearsals of this part for the final piece combined the skills of a dancer and a musician. The dancers are trained to study movements from video and memorize them, since there are no actual universal, modern system of notation of movements as in music. On the other hand, a classical trained musician can live a whole life without learning a piece by heart, since there is always an opportunity to read scores while playing. In the process with The Hands. The Double Ellen had to combine her experience as a trained classical pianist as well as establish new skills by studying and learning a set of complex movements by heart.

Part Four

The last and final part of the piece consists of a series of piano chords, samples of Ellen’s voice, her live voice, and a series of movements where she rotate her upper body to alternately play at the piano and the sampler. My sketch from March 2020 was very simple and with a static toggle between piano chords and samples. In the final version of this part, I developed a more unpredictable rhythmical interplay between voice, samples, and chords. To develop the movements we had the help of Silje Aker Johnsen, singer and dancer. She participated in some of our workshops in parts of the process. In the following video Silje tries out different possible movements for this part, helping us to work on the rotation of the body.

We applied Silje’s ideas in the following work and mapped out the different samples of words on the keyboard, so that Ellen had to rotate her body and stretch out to reach the keys in her alternate playing on the sampler and the piano. By doing this, we managed to give the last part a simple and poetic expression: Ellen moving as a pendulum between piano and sampler, chords and words, a body rotating and arms stretching out in different directions.

Feedback and discussions

During our work in the project Extended Composition, the participants in the project group met for common workshops where we showed and discussed the works of the three groups.

Ellen and I received important feedback on our piece during these sessions, both on the material of movements and sound itself, but also the relationships between the movements and sounds, between the different parts, the overall form of piece, and much more.

The project group followed the work from the early start, just as we did with the all three groups in Extended Composition. In that sense, the group was the most competent to point towards new possible directions, problematic sides and deficiencies in the work, and contextualize it. We had an, for us, important feedback session in June 2020, where we both showed some of the videos from our workshops and Ellen performed the piece at the stage it was at the time.

The discussions following our presentation brought some new and important ideas and points of critique. Chrstian Blom talked about how the material in the piece tended to be in the same tempo both in movements and sound, and that the different parts could be more integrated with each other. He judged that the relationships between the music and the movements worked better when they were in the same tempo, and by that melted together, than in the parts where the piano was more independent and closed itself around itself. Christian Blom also problematized the size of the movement. More specifically that the small movements worked better than the big ones.

Shila Anarak pointed to the fact that the movements had to be tailored to Ellen’s body and movements. Anaraki defined an interesting split between contrasting types of material in the piece, which she called “mood” and “composition”. “Mood” being loose in its output, giving a feel of improvisation, and “composition” being stricter and formal. She was critical of the more composed parts of the piece.

Tanja Orning commented that a movement made for one body would not necessarily work for another body, stressing Shila’s point that the movements have to be made specifically for Ellen’s body. She also pointed to an interesting side of the work, that it at times creates a real counterpoint between body and sound. This was in line with my own ambition and intention, that the combination of movements and music should create layers in a musical polyphony.

Silje Aker Johnsen mirrored Christian Blom’s ideas that the three short parts needed to approach each other both in material and expression. She reflected on how the movements needed motivation and that this motivation should come from the rhythm. The music and the choreography should be created together, she postulated, so that a change in the movements would necessitate a change in the music. A final interesting issue was Silje Aker Johnsen’s questions about the motivation for the movements. She asked where this motivation should come from, either in the music or in the chorographical choices in the space.

Experiences from this work, and where to go from here?

Through the Extended Composition project, Ellen and I had the luxury of having the time to gradually acquaint ourselves with one another and gradually circle in on a common interests of exploring movements and music. Furthermore, we developed our devising method by rotating the roles as performers and composers. We were able to intergrade Kristin Ryg Hegebostad in the development of the piece. Affording us the opportunity to learn something new from our joint workshops, where the three of us tested out, discarded, improvised, played, learned new skills, explored, and stretched our limits. All this thanks to a project generous in time and resources. Equally important were the frequent meetings and discussions with the large project group ,and the feedback from the external advisers. The common discussions we had in the project group raised important questions about our skills, and when we were amateur and when professional, relationships between movements and sound, new roles and methods of working collectively and more.

The Hands. The Double has opened up a totally new area of opportunity for my artistic expression It has raised questions about how to compose with movements, the integration of the visual and auditive, and expanded my understanding of the polyphony of signs. It has questioned the roles of the composer and the performer, and what skills are needed to work in this artistic field. My next project coming out of this will have to be developed inside more traditional frames of time and resources, but the work with The Hands. The Double has given me tools, ideas and techniques for new inter-medial processes in the future, exploring the complex web of signs, meanings, and intertextuality in an expanded field of composition.

References:

Ciciliani, M: Music in the Expanded Field – On Recent Approaches to Interdisciplinary Composision, Darmstädter Beiträge zur Neuen Musik, Band 24, Mainz; Schott Verlag

Craenen, Paul; Composing Under the Skin, The Music-making Body at the Composers Desk

Leuven University Press

Chion, M: (1993) Audio-Vision, sound on screen. Colombia University Press

Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/peirce-semiotics/