Etymologists debate as to whether the verb "concertare" is of Latin or Italian origin, as it would have very different meanings. On one hand, this term, "to strive or struggle" in Latin, emphasises the concerto's aspect of contrast, where the soloist is pitted against the ensemble. Contrarily, the Italian verb "concertare" would rather mean "to coordinate a heterogeneous group", which underlines the feature of uniting in harmony1.

After its initial use in the early 16th century, the term "Concerto" remained vague in its precise musical definition because the understanding of the term seems to have changed through time and geography. When it initially came into existence, this terminology was used to describe only vocal music. Nevertheless, the term "concerto" started to be solely connected with instrumental music near the end of the 17th century. The earliest type of purely instrumental concerto to appear was the concerto grosso, in which a small group of instruments (the concertino), collaborates with a larger group of instruments (concerto grosso or ripieno).

The common instrumentation of the concertino, comprising two violins, a cello, and a basso continuo, is exactly the same as that of a trio sonata, hinting that the concerto grosso may have been conceived as an expansion of the trio sonata. The ripieno, in which parts are freely duplicated, is usually divided into the first and second violin, violas, cellos, and basso continuo. Sometimes wind instruments are added, usually doubling on the same parts.

Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) was the one who standardised this form with his Concerti Grossi Op.6, composed in the 1680s, From there, we can draw a direct parentage in this celebrated Italian Concerto tradition: the first solo concerto for violin was first written by Giuseppe Torelli (1658-1709), and was widely popularised by Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741).

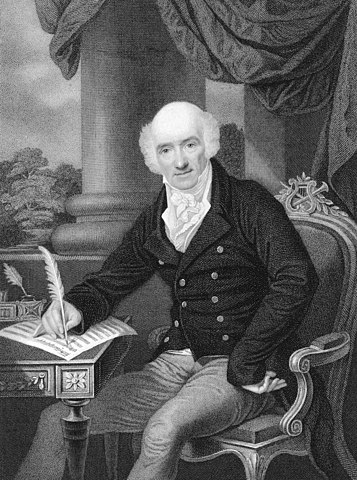

Antonio Locatelli (1695-1764), Giuseppe Tartini (1692-1770), and Pietro Nardini (1722-1793) continued developing this form, and this is the point where Giovanni Battista Viotti (1753-1824) takes over from.

It might seem unfair that in order to speak of Libón we have to refer to him as “the pupil of”; but in this case, the figure of Viotti is much too prominent, and his influence on Felipe too strong to be overlooked.

Giovanni Battista Viotti was the most celebrated violinist of the late 18th century and the most influential violin composer of his generation. An Italian by birth, he achieved great fame in Paris; after that, he spent his life intermittently between London and the French capital, affected by the rapidly shifting social, and political changes.

He was the last violinist from the renowned Italian School of the 18th Century who pioneered as the violinist of the modern French Violin School, in which Libón would take part. Viotti was truly the link between these two formerly antagonistic schools, and he created such a lasting impression on his students that led to this unusual case where the disciples founded the school to emulate their master.

Baillot describes this violinistic lineage in the following paragraph2:

This instrument, made to reign supreme over ensembles and to obey every flight of genius, has taken on different characters as required by the masters: simple and tuneful under the fingers of Corelli, harmonious, touching and graceful under the bow of Tartini, suave and amiable under that of Gaviniés, noble and grand under that of Pugnani, full of fire, full of audacity, pathetic and sublime in the hands of Viotti. It has risen as far as to depict the passions with energy and with a nobility matching its rank and the power it exercises over the soul.

Viotti was a pupil of Pugnani, studied in Turin, and got in close contact with the world of opera, which was very prolific in this city. Together with his mentor, Viotti began a European tour, leading him to settle in Paris. The Parisian public warmly welcomed Viotti. He worked in a number of opera houses in addition to giving frequent performances in open concerts and serving at the Court of Versailles for a period.

He moved to London in 1792 when his prior royal ties turned into a disadvantage. He frequently performed in Salomon's concert series and served as the new opera concerts'

musical director, while also being the star of Haydn's benefit concerts, and conducting the Italian opera at the King's Theatre. Moreover, he also took his instructional work seriously, teaching students like Rode, and the our dear Felipe Libón.

Viotti was expelled from the country in 1798 by the British administration, who suspected him of involvement with the Jacobins. After spending a few years in Germany and living away from the public spotlight, he became a naturalised British citizen in July 1811 thanks to the intervention of his friend, the Duke of Cambridge. Viotti now led orchestras and played in chamber ensembles rather than as a soloist, and he eventually returned to Paris and served as director of the Académie Royale de Musique from 1819 to 1821. In 1823, he travelled back to London with Margaret Chinnery, where he passed away.

Viotti was primarily interested in writing music for his own instrument. He never produced any orchestral works, and the violin dominates most of his chamber music. He was a prolific but rather traditionalist composer who did not participate in the popularity of sonatas for piano and violin or add formal innovations to his quartets the way Haydn or Mozart may have. His 29 violin concertos, nevertheless, display some of his most remarkable innovations. Paris led Viotti to introduce more drama and lyricism into his concerto writing. In contrast, the London concertos are again more classical.

Many of his works, such as his duos for two violins, had a pedagogical purpose and were marketed to the amateur market, who would buy his publications. He also wrote Sinfonias Concertantes — a concerto for two instruments or more, very popular at his time - which he frequently performed with his pupils—.

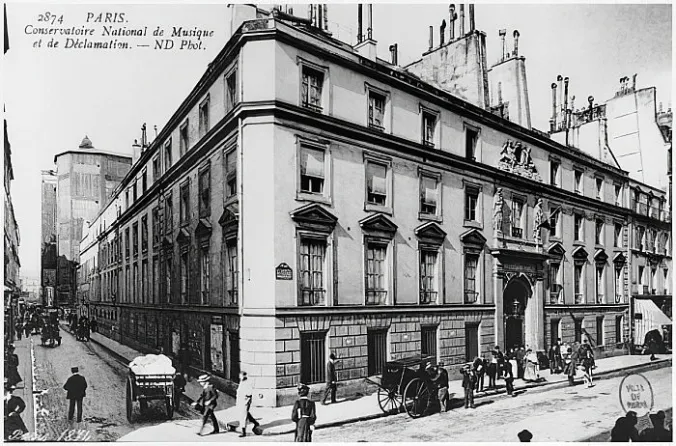

The French School of Violin Playing was founded within and at the same time as the Paris Conservatoire of Music. Its success contributed significantly to the institution's accomplishment, which would serve as a model for all conservatories to follow thanks to the violin's dominant role in comparison to other instruments at the time, and also to the work of Pierre Baillot (1771-1842) and his fellow violin professors in Paris, particularly Pierre Rode (1774-1830) and Rodolphe Kreutzer (1766–1831).

All three can be defined as disciples of Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755-1824), although only Rode was actually his pupil. In collaboration with Kreutzer and Rode, Baillot wrote his official violin method, which was issued by the Conservatoire in 1803.

Viotti's playing was renowned for its virtuosity as well as for its beauty of sound, power, and expressiveness, and the Méthode was written with the distinct goal of establishing this style as the standard.

Macnicol points out the change in language and emphasis to negotiate shifting cultural currents when comparing the two editions of Baillot’s treatises: the first one was published in 1803, and the second one in 1834. While one represents a manifesto — an idealistic statement of intention —, while the other seems more like a testament, giving an account of the accomplishment. In the 3 decades that set apart the two editions, we have to take into account that the monarchy was re-established in France, which explains the noticeable change in the author's stance. Moreover, the musical scene had undergone some important structural changes, as well as the labour related to music, which ties into the brand new skill that a performer must have.

In addition to playing their own compositions, Baillot and Spohr were the first notable violinists who mastered the new technique of "interpretation"; performers who were able to modify their playing to fit the various compositional approaches of other composers. This talent is lauded by Baillot under the description le génie d'exécution.

One clear difference that can be found is that the latter includes a more insistent positioning of the School in a historical tradition. More striking is the fact that in this new 1834 edition, Baillot lists the old Italian violin masters and adds the names of his recently dead colleagues Kreutzer and Rode, while doing a direct plea to uphold their legacy: “In you, their talents will live again: as conservators of their traditions, you will prevent the chill hand of forgetfulness from falling on their works”. We can understand this change of tone as a mission statement: tradition now is not only an inspiration but an obligation.

As noted above in the first section about its origin, cultural nationalism was at the heart of the Conservatoire enterprise. There was a clear desire for the institution to add to France's greatness. The violin school was successful in achieving this, and the 'School of Viotti,' as it was originally called, quickly became the gold standard for bowing technique, taste, and virtuosity.

Unfortunately, under the pressures of the Bourbon Restoration, when the Conservatoire found itself under attack as a Revolutionary institution, what Laetitia Chassain calls "the autarchic ideal" could easily — and did — become protectionist3. This was when foreigners had forbidden entry into the Conservatoire, as Franz Liszt’s visit to Paris in 1823 gives testimony. Director Cherubini, despite his being a foreigner himself and in spite of the young man’s evident talent, refused to relax this rule.

Moreover, as stated in point 4 of the objectives dictated by the Conservatory, establishing a 'supremacy of taste' was one of the aims of the French school. This was reflected in the total rejection of the shiny showmanship shown by virtuosos such as Paganini, who will identify these features as empty and of a foreign, “lesser taste”.

On the other hand, some scholars, such as Rubinoff (as cited in Macnicol, 2020) make the case that the Conservatoire's success was based on a new, military style of instruction. This was suitable for producing disciplined foot soldiers for the growing symphony orchestra at the expense of more artistic and improvised aspects of music-making. She points to the military origins of the institution of music education for wind instruments to argue that the teaching methodology used at the Conservatoire was intended to produce instrumentalists who were incapable of playing anything other than what was written on the page in front of them.

Rubinoff leaves us a margin in which admits that the violin, given its role as a solo instrument, may not have been subordinated to these afflictions. However, her article serves as a useful resource for the conclusions she draws about the Conservatoire's guiding principles and it presents us with an idea that we can connect with "le génie d'exécution" that Baillot referred to in the previous point. This depicts how the profession of the musician, the ideals, the aesthetics, and the skillset that have to offer had changed drastically after the French Revolution.