3.2 Andalucia as the imaginary orient

The subjectivism and individualism1 that guided Romanticism led to another identifying feature of this movement: the escape from reality to idealized paradises and exotic places. It is the nostalgia for times of the past more splendid than the one that is lived at that moment.

In its search for places of escape, Europe discovers in Spain one of those earthly Edens, creating an imaginary Orient to its measure.

“Spain is very present in European romanticism, in literature from Madame de Stäel, Schlegel, Byron, Humbold, Roberto Southey, Victor Hugo, Gautier, Musset, Merimée, and in painting: Manet and Doré. But also in music it is observed especially in works such as El trovador, Don Carlo, Ernani, La forza del destino by Verdi, The bullfighter and the dancer by A. Rubinstein, the Capricho Español by Rimski-Korsakov, the Fantasy on Spanish motifs by Gevaert, A night in Madrid by Glinka, the Spanish Rhapsody by Liszt, Carmen by Bizet, Spain by Chabrier or The Spanish Symphony for violin and orchestra Op. 21 by E. Lalo.”2

What most attracts the attention of Spain is Andalucia. From 1830 to 1860 it was witnessed a wave of "Andalusism" that swept the arts. An agitated Andalusianism that was very artificial and stereotyped, created mostly by foreigners. "The Andalusian, the gypsy, the bullfighter and the flamenco were in style. Victor Hugo's Esmeralda, Merimée's Carmen or Bizet's Carmen are interpretations that the French make of Spanish gypsy women, free, unprejudiced, natural women and brave"3

That stereotyped concept of the Spanish people in Europe could have its origin in the stories and anecdotes of French soldiers who participated in the War against Spain, called in the country the War of Independence.

This trend was economically and creatively taken advantage of by various foreign authors, who after traveling through Spain, especially in the south, gave free rein to their literary fantasy.

“Foreigners will play a fundamental role in the discovery and revaluation of a part of Spain that went unnoticed in the eyes of the natives. This is confirmed by the number of books they published on their trips, which always had Andalucia as their final destination. Let's not forget that the neighbors from beyond the Pyrenees were really the inventors of literary espagnolade, which is nothing more than telling a story that takes place in the romantic Spain, and including most of the typical Hispanic costumbrist clichés, and the which, Carmen de Prosper Mérimée is the maximum representation. It is true that these neighboring writers projected a partial and novel image of the Hispanic, which also worked very well artistically and economically, both in France and in Spain, as is no less, than some characters from stage Andalucia, which they would hardly have reached the prominence they did, if they had not been for the interest they aroused among these romantic travelers.”4

3.3 The music in XIX in Spain

Music during Romanticism was composed in two contrasted types of format:

- On the one hand, increasingly spectacular operas and symphony concerts destined for the great concert halls.

This format will require larger and larger orchestras until it reaches dimensions never seen before.

- On the other hand, the lounge and chamber music pieces for smaller rooms and intimate settings.

The bourgeoisie became the main consumers of this last type of compositions, either as amateur performers or as listeners, with domestic concerts or musical events in halls being a type of social gathering. Composers, eager to publish their music, benefit from this phenomenon and compose an infinite number of easy and short pieces for this audience.

In the Spain of the first half of the 19th century, however, there weren't large concert halls or buildings to host great operas. The Teatro Real dates from 1850 and the Liceo de Barcelona from 1847...

Concert halls and cafés, as well as musical theater, became the main centers for the diffusion of romantic music.

The music in these cafes and lounges, played mainly on the piano, will be playful and quasi-decorative. A wide variety of pieces are produced: the evenings usually began with some Italian aria and followed with dances of various origins (waltzes, polonaises, etc.), fantasies, variations on operatic themes, or marches.

The Hispanic-tinged pieces could not be missed, written for solo piano or as voice accompaniment. So much so that there is even talk of the salon genre from the sixties (of the 19th century).

Precisely from that date, musical theater became one of the pillars of Spanish romanticism thanks to the construction of musical coliseums in the main cities (Madrid, Barcelona, Bilbao...). According to Casares and Alonso (1995) only in 1861 eight thousand dramatic performances, three thousand zarzuelas and one thousand opera performances were performed in Spain.

Associationism (another important and characteristic point of this century) will promote the creation of athenaeums, high schools, (later conservatories) and various institutions dedicated to the cultural activities of bourgeois society.

Various currents and ideological-musical movements developed in these centers that would lead to the golden age of music criticism and publishing houses.

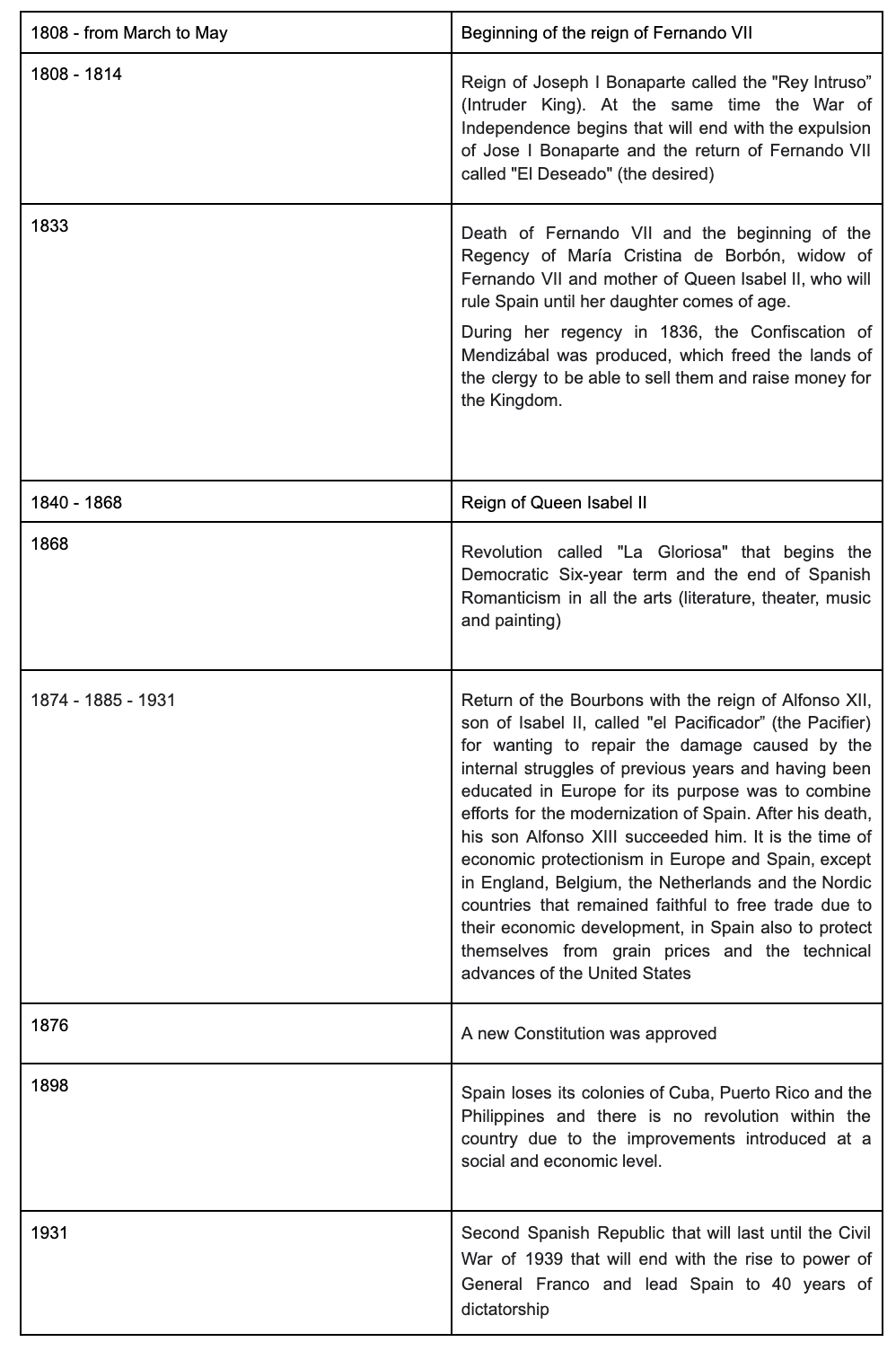

Very active critics were Peña y Goñi, Esperanza y Sola, Alejandro Saint Aubín, Pascual Millán and Félix Borrell. Other professional musicians frequently made their opinions public. Due to the confiscations of 1835, the musical centers around the cathedrals and ecclesiastical chapels ceased to be hardly a possibility for the musicians, who had to look for other resources to be able to earn a living.

The piano is the instrument par excellence of romanticism and in Spain it will not be an exception.

From the fifties the volume of music published for this instrument increased notably, especially pieces for singing with piano accompaniment, as well as arrangements, transcriptions and reductions for solo piano.

In this production two types of compositions are distinguished:

-The virtuosic ones for soloists

-The extremely simple ones, intended for an amateur audience, their main “performers” being well-to-do bourgeois ladies who included the piano in their education.

Pieces by Moscheles, Klakbrenner, Chopin, Liszt, Thalberg or Cramer coexist, with a clearly Hispanic piano (jotas, malagueñas, chotis, zortzicos, habaneras...).

Regarding the form used, the European trends that used the free form of the rhapsodic or programmatic type are followed. In 1874, 6,000 works for this instrument were published5.

This piano-loving bourgeoisie required not only an affordable repertoire but also a teacher to guide their steps. Piano lessons then became an economic resource for many composer-pianists. Songs with piano accompaniment with Spanish gracejo is one of the types of composition most loved by the public. More than 4,000 were published in this century.

“Along with the piano, the song with accompaniment is the most important nucleus of the edition, precisely because it was the most popular and had a broader social extension, from the so-called Andalusian or Spanish songs, widely cultivated since the beginning of the century, until its emergence through different stages. Authors like Hernández, Iradier, Inzenga or Álvarez are a symbol of this publishing success.”6

The guitar acquires a new editorial dimension with composers such as Fernando Sor, Julián Arcas, Campó y Castro, Broca, Cano, Damas Ferrer and Fernando Tárrega.

Happens as in the case of the piano, the guitar becoming a vehicle to reproduce the music that is in the environment with multitudes of transcriptions. Compositions for military bands are quite common, with marches later being arranged for piano or guitar.

The birth of Spanish musicology as a product of nationalist thought also dates from this century.

The interest in the "national glories" of the past led intellectuals to get involved in the rediscovery of the music of other centuries. For example, the rediscovery of Tomás Luis de Victoria and the complete edition of his work in Leipzig (1902-1913) is due to the studies of Felipe Pedrell.7

In the same way, the incipient musicologists, with the purpose of revaluing the popular culture of the country, began to compile the national folklore through the famous songbooks (cancioneros).8

Undoubtedly, musical nationalism occupied the 19th century in Spain, at first as a small note of local color, and later it ceased to be an aesthetic option to become a constant: "Nationalism, even unconsciously, emerged in the first decades of the century, it is felt in all the constitutive elements of music, form, harmony, melody, cadences, ornaments. That is where the concept of nationalism begins."9

To conclude, the most influential groups of composers in the 19th century:

- Ramón Carnicer, José Melchor Gomis, Trinidad Huerta (also a guitar soloist), Fernando Sor, Andreví and Pedro Pérez Albéniz, founder of the Spanish piano school (who has nothing to do with the other Albéniz in question).

- Those born around 1811 (contemporaries, therefore, of Franz Liszt): Saldoni, Hilarón Eslava (author of the famous Solfeggio Method, 1846), Obiols, all of them with a strong Italian influence.

- The next generation (1826) fully romantic in thought and with a certain dose of patriotism: Barbieri, Arrieta, Aranguren, Gaztambide, Marcial de Adalid, José Inzenga, Julián Arcas... This generation will focus its efforts especially on the lyrical theatre.

- The group born around 1841 begins the current of nationalist thought, also characterized by its musicological and critical work in Spain: Eduardo Ocón, Felipe Pedrell, Guillermo de Murphy, Peña y Goñi, Chueca, Jesús de Monasterio, Sarasate...

- And finally, the already fully nationalists: Bretón, Chapí, Serrano, Tragó, Bosch, Isaac Albéniz, Fernández Arbós, Granados, Conrado del Campo…

3.4 Musical nationalism in Spain

The concept of Nationalism includes connotations of a diverse nature that are often distorted. Refered only to what concerns the birth of musical Nationalism.

Even for some authors, such as Tomás Marco (2005), this term is not entirely appropriate, because even if the movement was born linked to political nationalism, it should be called folklorism, since certain elements of folklore are adapted to academic musical activity. Although it is true that this use has a nationalist purpose, there are musical nationalisms that do not make use of their folklore. The use of the popular in what has been called cultured music or serious music is, however, much older.

In this section I will focus only on the nationalist school of the 19th century. The subdivision of this period made by the cited author seems appropriate, and I summarize it here:

- First stage: romantic nationalist folklorism. He started from the false idea that serious music was not interested at all in folklore. And even the main European musical powers are accused of lacking an authentic folk oral tradition. Obviously this sentence is false and is clouded by the proper nationalist mentality. To dismantle this idea, take the example of Beethoven, who replaced the courtly minuet with the popular scherzo. Let's remember that he also composed Scottish and even Spanish songs. Or let’s remember the case of Chopin who composed on the popular Polish airs of mazurka and polonaise. Without forgetting the alla turca fashion that crossed the eighteenth century. This is what the author calls tourist nationalism.

- Second stage: folklorism of the construction of modernity, with an internationalist base. The difference with the previous one is that it is not a question of coloring the pieces of cultured music with folkloric motifs but rather transforming cultured forms from popular music. That is, to reconstruct the popular. This is the case of Albéniz’s Iberia.

- Third stage: postmodern folklorism. Traditional musicology shows that musical nationalism is born with attempts to create national operas in the vernacular. Attempts that, although they prospered in Russia or Bohemia, in other countries such as Hungary or Poland did not transcend their borders. Operas were created around epic-mythical themes of the popular tradition of each nation and folkloric musical elements were added to give a bit of local color to the works that, with few exceptions, followed the form and structures of cultured music of Central European tradition.

I will start from the immediately preceding antecedent: the tonadilla10, to understand this phenomenon:

“The tonadillesco genre contributed to the creation of a musical nationalism through the association of the character-type from theatrical use and the incorporation of musical patterns assimilated to the area that it was intended to represent. In such a way, that those then considered national dances, when represented together with specific provincial types, will end up forming part of the specific typicality of said region, and consequently, becoming regional dances. In such a way that the actor who represented an Andalusian, in addition to dressing in the best way, speaking Andalusian about the theater, wearing sideburns like an axe, a dark complexion, a guitar on his back, compliments and being continually funny, he was identified musically by a rondeña, a seguidilla, a fandango, a zorongo, the olé, etc. notwithstanding that this musical association was rigorously true or not. The old tunes would gradually disappear from the scene, defeated by modernity.”11

Musical nationalism is something more than the exaltation of popular types or a current of manners. It is the search for their own brilliant identity of a group of intellectuals who seek to revive a sleepy country and which carries an absolute lack of cultural self-esteem.

According to Casares and Alonso (1995), nationalism, born as an ethnic expression that spreads throughout the century, has as its claim the exit of music from an identity crisis. It becomes the basis of Spanish romantic music, a natural quality of it.

In Spain, the music scene suffers a great backwardness due to wars and political instability. This obviously leads to an inferiority complex that has run deep into the cultural elite.

At the beginning of the century, Italian opera reigned in musical Spain. Against this predominance, criticism and anonymous writings arise in the twenties. From there, the thought around musical creation will tend to the production of nationalist essence. What does this mean?

As previously said, one of the romantic standards is the search for exotic places or a return to glorious pasts, to escape from the sad reality that is lived.

This is the key that will make intellectuals interested in the historical past of the country, therefore immersing itself in the folkloric roots, a sign of the ethnic identity of each town. This aroused feelings of self-affirmation and pride that led to nationalism that exalted the unique and identifying (and differential) characteristics of each nation, thereby trying to overcome that inferiority complex.

Historical restoration takes its sense from nationalism. It is an important ingredient in the intellectual life of that time that powerfully influenced the composers and their music, and this is essential to understand romanticism in Spain.

All the efforts of the Spanish musical authors (Soriano, Barbieri, Inzenga, Hernando, Eslava, Saldoni, Pedrell) are then focused on the production of a purely Spanish opera, in opposition to the Italianizing Rossinian invasion. The creation of an opera that would be in Spanish (and even in some cases in Catalan, Galician or Basque) arguing the richness of this language and the beauty of the phonemes, especially the vowels (optimal to be sung as opposed to the dark vowels or nasals of other languages).

"Isn't it shameful that the Italians, the French, the English and even the Russians have a national opera and that we don't?"12

“All nations have protected musical art...And in Spain, what has the government done to protect it? Doesn't one's heart break when seeing someone who yesterday was applauded as a composer apply today for a position as a music copyist?... The truth is that Spain is the most backward nation of all musical nations”13