ther Distinguished Vihuelists

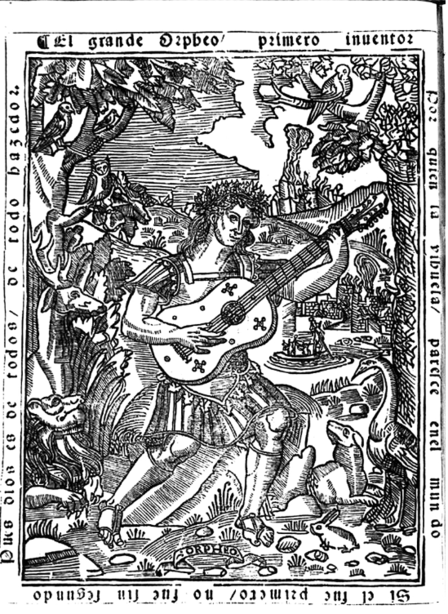

Luis Milán (1490/1510 - after 1561) is the author of the first printed collection for vihuela El Maestro (1536). He was a noble man from Valencia, vihuela player and a writer associated with the court of the Duke of Calabria and his wife Germanie de Foix between the years of 1526 and 1538.57 His life in the court is described in Milán’s El Cortesano. Although this book was not originally intended as an autobiography, it contains several episodes describing the life of a vihuela player, including moments when the vihuelist is entertaining listeners by telling stories and accompanying himself on vihuela. It may have been necessary to be endowed with musical skills to keep the audience’s attention during longer stories.58 Although Milán called himself The Second Orpheus, there is little evidence for his fame. In the year 1538, Luis de Narváez believed that his own collection was the very first published composition of vihuela music, and Juan Bermudo did not name Milán as one of the most important vihuela players of the time. Despite this, his name appears in other publications, such as Diana Enamorada written by Gil Pol in 1564.59 Milán dedicated his El Mastro to The King of Portugal João IV.60 This collection contains approximately fifty solo pieces for vihuela and twenty two songs with vihuela accompaniment written in tablature. It should be taken into consideration that the compositions by Milán are mostly written as improvised music originating on the vihuela as Milán described.61

This indicates that the compositions were invented on the spot, played and later written down in tablature.62 Luis Milán was proclaiming himself to be “The Second Orpheus”, also pictured as the adherent of Orpheus like in the preface of El Maestro confirming this statement with the text hemming the engraving.63 He was comparing vihuela to the Orpheus’s Lyra. In a comparison with later publications, it is remarkable the absence of the intabulation of sacred pieces in El Maestro. Luis Gásser is introducing a theory about Milán’s religious orientation being converso (a Jew who converted to Catholicism) supporting his theory with also with the dedication of El Maestro to The King of Portugal despite the fact that Milán was sponsored by The Duke of Calabria and Germanie de Foix. The Inquisition was not so active in Portugal, where a lot of converted Jewish people took refuge.64

Luis de Narváez was a renowned composer and vihuela player during his life time as we know from the writing of Luise Zapato:

“During my youth, in Valladolid, there was a vihuela player Narváez, who was extraordinarily skilled. He was able to add one more voice to the four already written. An unprecedented thing for whose who do not understand music and a miracle for those who do." 65

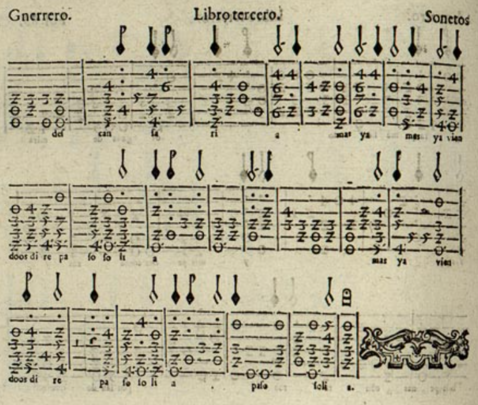

His art was also known also outside of Spain, as his compositions were added to several publications including lute collections of Guillaume Morlay (Paris, 1552), lute collections of Pierre Phàlese (Leuven, 1546, 1522, 1568) or his motet De profundis clamavi66 was published by J. Modern (Lyon, 1539) in the collection Quartus liber, Motteti del fiore.67 It is unfortunate that despite his fame, limited information about his life remains. He likely grew up in Granada, but moved to Valladolid at a young age to join the house of Francisco de Cobos, the secretary of King Charles I. In 1536, Narváez traveled with the King to Rome, where Charles was introduced to the pope as the Holy Roman Emperor. This journey was crucial for Luis de Narváez too, as he was introduced to the papal lutenist Francesco da Milano. After the death of Francisco de Cobos, Narváez’s name appears in the list of employees of the royal court.68 His book Los seys libros del Delphín de música de cifra para tañer vihuela was published in 1538 in Valladolid and contributed significantly to the canon of vihuela music. This collection does not have the methodological structure like El Maestro and the vocal polyphonic influence is more noticeable, as is exemplified in the intabulated pieces by Josquin de Préz, Nicolas Gombert and Jean de Richafort.69

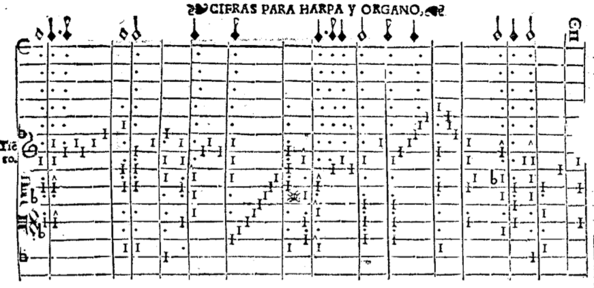

Alonso Mudarra (1505/1510 - 1580) was associated mainly with two cities: Guadalajara and Sevilla, where he spent the majority of his life. The greater part of the information we have nowadays comes from the research of Emilio Pujol and is published in his Tres libros de música de cifras in 1984. Pujol assumes Mudarra’s year of birth according the publishing date of his collection for vihuela, or according the year of Mudarra’s ordination to the priest. He presumably spent his childhood in Guadalajara in Palacio del Infanado, where he was in the service of the Dukes of Infanado for several years (Diego Hurtado de Mendoza and Iñiga López de Mendoza). As Guadalajara was an important cultural center, it is almost certain that he studied theology and philosophy and likely also received his musical training there.70 It can be also assumed that Mudarra took part in the expedition accompanying King Charles I. to Bologna in 1530 with the Duke Iñigo López de Mendoza in 1530. The King was accompanied by many subjects including several prominent musicians.71 In 1546, Mudarra was ordained as a priest in Seville Cathedral, where he worked until the end of his days.72 Mudarra’s main work is his collection Tres libros de música de cifras from 1564 containing compositions for vihuela de mano, renaissance four course guitar and voice with accompaniment. Mudarra also introduced a system of tablature for a harp or organ, however, compositions for those instruments do not appear in the collection.73

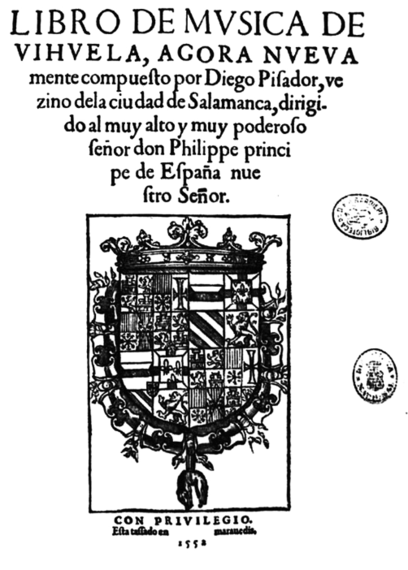

Diego Pisador77(1509/1510 - after 1557) is a rather controversial figure in the vihuela world. He was born around 1509 to parents Alonso Pisador and Isabel Ortiz. His mother was probably the illegitimate daughter of Alfonso de Fonesco III, who served as Archbishop de Santiago and was a great patron of artistic and musical life in Salamanca. Pisador likely received his musical education in the Cathedral of Salamanca,78 where he later became a member of the monastery. It is possible that this is where he met Francisco Daza, whose grandson was the vihuelist Esteban Daza. After his mother’s death, Diego Pisador used much of his estate funds to print his vihuela book Libro de la música de vihuela.79 He got into a dispute with his brother over this. Pisador counted on the support of his father, who tried unsuccessfully to convince him to abolish the publication of his book. His father eventually gave him a considerable sum of money to pay off the debts associated with Libro de la música de vihuela, which was eventually published in Salamanca in 1552. Pisador is said to have worked on this collection for fifteen years, which would mean that he began writing it before Milán’s El Maestro was published.80 The controversial nature of this author has been pointed out, for example, by musicologists Francisco Roa and Felipe Gertrúdix. In their opinion, he was not a very talented composer, as evidenced by the frequency of intabulations of works by Josquin de Préz (eight complete masses). Pisador is criticized for his low level of compositional technique compared to other vihuelists, mainly due to the poor overall quality of his music and the significant number of errors in his publication.81 It remains unknown if, judging by the high number of intabulated maasses he included in Libro de la música de vihuela, he was merely trying to please his patron Philip II.

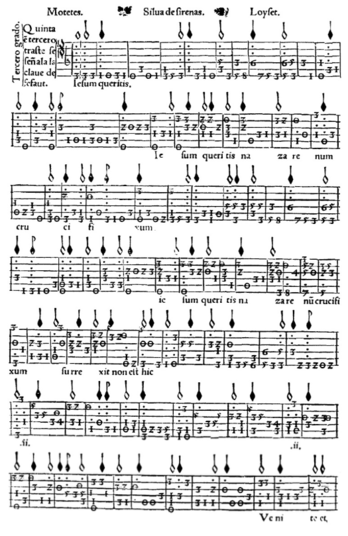

Enríquez de Valderrábano belongs to a group of authors about whose lives we have almost no information. There are several hypotheses about his place of birth. Some sources describe his birthplace as Peñaranda del Duero, according the note in Valderrábano’s vihuela book. Here it is mentioned just as vecino (the modern translation would be a neighbour and other possible translation would be taxpayer). Another possibility might be the city Valderrábano de Valdavía, however, the only indicator is the frequency of the surname Valderrábano in this area.74 The only evidence found is the year 1547, when his collection for vihuela Libro de la música de Vihuela intitulado Silva de Sirenas was published in Valladolid. This anthology is dedicated to Francisco de Zuñiga, the Count of Miranda. It has been recently confirmed that Valderrábano was in his service.75 The Silva de sirenas is quite extensive. After the prologue containing detailed information especially about playing from tablature, follow six books divided by the context. Besides fantasías composed by Valderrábano himself we can find within the books a significant number of intabulations of vocal pieces by authors such as Josquin Despréz, Nicolas Gombert, Fernando Layola, Cristóbal de Morales, Vincenzo Ruffo, Jean Mouton and others. Valderrábano thus demonstrates his extensive knowledge of the contemporary production of European vocal works.76

Esteban Daza (ca. 1537 - fl. 1591) was born in Valladolid to parents Tomás and Juana Daza. He was the first born of fourteen children. He came from a respectable bourgeois family. Their important social status can be inferred by their ownership of a private chapel in the church of San Benito el Real, which was one of the most important churches in Valladolid during that time. Esteban Daza was educated either at the University of Valladolid or at the University of Salamanca, where he likely studied law.82 In 1569, after the death of his father, he became the head of the family and took care of his mother and siblings. During this period he decided to write his vihuela book El Parnaso, with the support of his colleagues.83 Possibly Daza's most important professional relationship was with Hernando de Hábalos de Soto, a lawyer of the Royal Chancery and a member of the Royal Council, to whom Daza dedicated his collection when it was completed in the spring of 1575.84 It remains unknown where Esteban Daza received his musical education. One hypothesis is that he was a pupil of one of the renowned vihuela players who were active in Valladolid at the time. Luis de Narváez probably lived in the same neighborhood for the first twelve years of Daza's life. However, it is certain that Daza was knowledgeable about the collection of the older vihuela masters. He was even inspired in his first fantasia by the compositions of Alonso Mudarra and he also demonstrates a close connection with the compositional styles contained in the treatise Libro llamado Arte de Tañer Fantasía by Dominican friar Tomás de Santa María.85 Esteban Daza never married and lived the majority of his life with his younger brothers. One of the last mentions of this vihuelist is from 1589, when he moved to the parish of San Ildefonso.86