Mediating elements. Crossmodal correspondences

Early on during the research process, I came across the notion of 'crossmodal correspondences', which might be defined as “consistent mappings between attributes or dimensions of stimuli (i.e., objects or events) either physically present (or else merely imagined) in different sensory modalities, be they redundant (i.e., referring to the same stimulus attribute) or not” (Knöferle & Spence, 2012, p. 993). Or, as Spence & Wang define them in the realm of wine and music matching, “the associations that the majority of us share between tastes, aromas, flavours, and mouthfeel characteristics on the one hand and particular properties of sound and music on the other” (2015, p. 1). I was pleasantly surprised to find out that a lot of research has been carried out in relation to these crossmodal correspondences in the past years, particularly in the field of experimental psychology (for those interested in reading more about this, I point out some of the most relevant literature in the section Current state of knowledge).

As I found an abundance of papers describing crossmodal correspondences between sounds/music and tastes/flavours, I decided that it might be interesting to use them as a basis for the food and music pairing I would be attempting during my first experiment. I chose to focus on research that related four basic tastes (umami was not included in most of the studies) to different auditory or musical properties. The auditory properties I chose to take into account were:

- Pitch (based on a study by Crisinel & Spence, 2010*).

- Roughness (based on a study by Knöferle & Spence, 2012*).

- Discontinuity (based on a study by Knöferle & Spence, 2012*).

- Articulation (based on a study by Mesz et al., 2011*).

- Harmonic & melodic consonance (based on a study by Mesz et al., 2011*).

(*The information from all of the previously cited studies has been taken from Knöferle & Spence, 2012, p. 997.)

This allowed me to define the following attributes for the music that would match each of the basic tastes during the experiment:

- Sweet: (relatively) high pitch, low degree of roughness, low degree of discontinuity, legato articulation, low degree of melodic and harmonic dissonance.

- Sour: (relatively) high pitch, high degree of roughness, high degree of discontinuity, average articulation, high degree of melodic and harmonic dissonance.

- Salty: average pitch, average degree of roughness, high degree of discontinuity, staccato articulation, average degree of dissonance.

- Bitter: (relatively) low pitch, high degree of roughness, high degree of discontinuity, legato articulation, average degree of dissonance.

Having thus defined the attributes of each of the different musical materials, and having decided that the music would be composed for traverso and baroque violin, the most immediate issue that sprang to my mind was that the pitch range I would be working with would be fairly limited, as the traverso and violin have a rather similar range. If I wanted to have a perceptible difference in pitch between high, average, and low, as was required by the musical parameters defined above, I would have to split the pitch space that was available to me in a very clear manner. I decided to divide it into three different octaves, starting on the open G string of the violin, the lowest note that would be available to me. G3-F#4 would therefore be the pitch space the bitter material would be bound to, G4-F#5 would harbour the salty material, and the sweet and sour material would be confined to G5-F#6.

Once this was determined, I proceeded to compose the musical material corresponding to each basic taste:

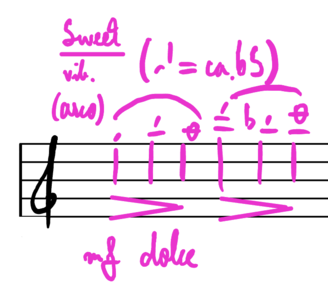

- ‘Sweet’ musical material: I decided to use two distinct musical gestures to represent the sweet taste, as I knew I wanted to have a progression from fairly little sweetness to a very pronounced degree of it during the experiment. It would first be represented by a single suspended long multiphonic on the flute, a material that would find its equivalent in the violin part as a harmonic double stop. Later in the piece, I would incorporate another 'sweet' gesture, which would more explicitly explore the qualities of "legato articulation” and “low degree of dissonance”.

- ‘Sour’ musical material: I decided that a ‘flatterzunge’ sound on the flute and a tremolo on the violin would surely comply with the definition of “high degree of roughness”, especially if combined with an accented articulation. A quick diminuendo on each note, in addition to a somewhat unpredictable rhythm, a different pulse in the violin and flute parts, and the fact that the material would be presented in short utterances, would provide the “high degree of discontinuity” that was required.

- ‘Salty’ musical material: the “high degree of discontinuity” would this time be achieved by a quick accelerando and ritardando, or vice versa, over a short staccato/pizzicato utterance that would match the required articulation.

- ‘Bitter’ musical material: I decided that, since the presence of bitter taste was going to be rather low during the experiment, it would be enough to give this material to the violin and not the traverso, which had the additional advantage of the violin being able to play a perfect fifth lower and thus fit the selected pitch range more effectively. The “high degree of roughness” would this time be achieved by a strong attack of the violin on a double stop, and then a glissando that would either depart from or end in a unison, creating a strong clash between the two notes when close to the unison but not quite there.

(For a detailed account of how this material was organised in the music of the experiment, see the section Mediating elements. Structure, and the chapter The music.)

Conclusions to the use of crossmodal correspondences

On a personal artistic level, I did not find this use of crossmodal correspondences particularly inspiring. I had to adapt my musical language to mainly take into account the musical parameters that were evaluated in the studies I consulted. Timbre, which I consider to be the starting point of my compositional thinking, was notably absent from these studies (or only present in the sense of different instruments being associated with different tastes [see Crisinel & Spence, 2010, for instance], but not the same instrument making different sounds). In this respect, studies that link other types of sound (not necessarily music) to flavour/taste might have lead to more interesting results when applied to different instrumental techniques (see Simner et al., 2010, for instance). This being said, composers who do usually take (some of) the above described musical parameters as starting points for their pieces might find this a fairly straightforward way of approaching the creation of a score that matches a particular dish.

Further research in the use of crossmodal correspondences as a starting point to a food and music pairing might focus, as suggested by Spence et al. (2021), on creating music that might match “the specific temporal evolution of the flavour of a particular food or beverage product” (p. 15). This would undoubtedly be a fascinating endeavour, which might lead to an in-depth exploration of instrumental timbre.

Something else I noticed while designing this experiment was that this particular use of crossmodal correspondences brought me very close to the idea of ‘sonic seasoning’. I was rather keen on avoiding this, because of the clear hierarchy it establishes between the food and the music, the latter serving as a mere seasoning to the first. While during the experiment itself I doubt that this hierarchy was strongly perceived (the setting being that of a concert, which framed the music as an essential element of the performance), during the creation of both the food and the music I mostly based my musical choices on the food I would be serving, rather than the other way around. This is not something negative in itself, but I did feel that I was leaning towards this way of working more than I would have wished to.

The feedback I got from the audience in relation to the first experiment contained several interesting remarks. On the one hand, it was apparent from both the discussion that ensued the experiment and the audience’s answers to the questionnaire that, overall, the match between the second dish (a piece of Danish-style sourdough bread with kapucijner and wild garlic hummus, topped with a parsnip chip) and the music that was sounding while it was eaten was the most successful of the experiment. The audience’s comments as to why they had perceived it as such were however not related to the crossmodal correspondences I had based my pairing choices on, but rather on the texture of the dish and the music. One audience member remarked that the second dish “had a crunchy element […] [that] matched with the pizzicato and short notes”, while at the same time it had a “dense background that matched with the more melodic lines [of this dish as] compared to the first”. Another audience member, who also claimed to have found this match successful, mentioned that the bread of this dish “was more grainy and […] was separating while eating”. During the discussion, another audience member mentioned that the third dish (a piece of spelt, linseed, and parsnip cake) and its music had struck him as too contrasting because the lightness of the music seemed to contradict the density of the cake. I found this last remark particularly revealing, as the third dish was undoubtedly the simplest in its composition between the different basic tastes, the sweet taste clearly dominating over the others, and I had imagined it would be perceived as the most successful match.

These remarks led me to conclude that, while the crossmodal correspondences I had taken into account might have worked to make the match effective on some level, the audience was a lot more aware of the interaction between musical and culinary texture, which I decided to explore in more depth during the second experiment (more on this can be found in the section Mediating elements. Semantic matching).