I. Defining Ecoacoustics

It is essential to define ecoacoustics, as there are multiple definitions pertaining to different fields, though these definitions do intersect in a number of ways.

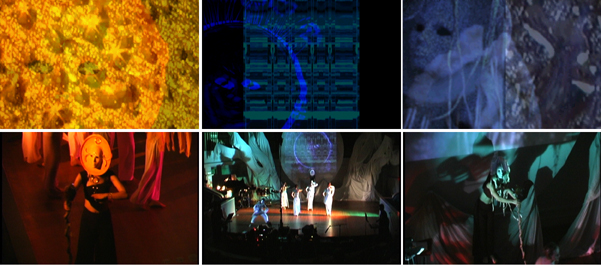

Matthew Burtner, a self-proclaimed ecoacoustic composer, defines "musical ecoacoustics" as embedding environmental systems into musical and performance structures by using new technologies: drawing environmental and ecological data from their domains into the musical realm.1

The data could be audio recordings or measurable information such as tidal frequency, temperature, or geological changes. The composer can develop their own syntax based on this information to compose freely, not confined to any one method or structure.

Ecoacoustics, as a scientific field outside of music, is defined by the International Society of Ecoacoustics as a science that "investigates natural and anthropogenic sounds and their relationship with the environment over a wide range of study scales, both spatial and temporal, including populations, communities, and landscapes."2

Almo Farina in his paper describes four domains that ecoacoustics studies:

1. Adaptive ecoacoustics, which explores the ways sounds in ecosystems help partition frequencies to reduce competition,

2. Behavioral ecoacoustics, which explores signals from anthropogenic and geophysical sources that help species find suitable acoustic habitats,

3. geographical ecoacoustics, which pertains to the geography of sounds, composed of sonotopes, soundtopes, and sonotones. This domain looks at an environment, these three entities nested within it, and the ecoacoustic events occurring within the soundscape.

4. Ecosemiotic ecoacoustics explores the way in which acoustic information functions and means something, on a species level. 3