Controlled Rummage Approaches for Bummock: Tennyson Research Centre

Sarah Bennett, Andrew Bracey, and Danica Maier

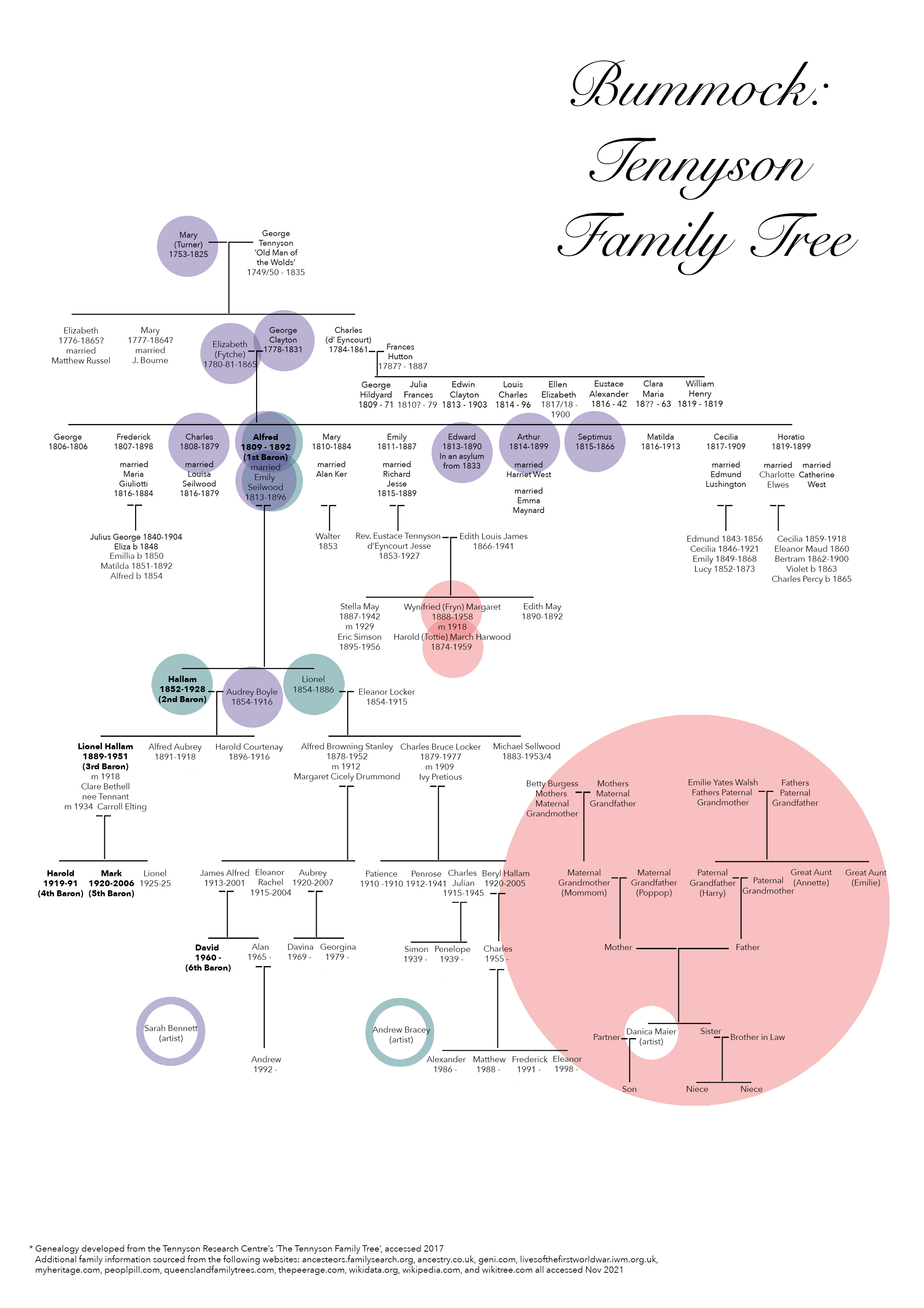

Each artist worked with specific family members as seen here within the Tennyson Family tree. The colour key below indicates which artists worked with which family member. For more detailed information about the family tree please go to the Controlled Page found here:

Historical archives, and what actually constitutes an archive, have been the focus of my artistic research for two decades. Preliminary questions emerged during doctoral research when I proposed that a building might, in and of itself, be considered as a self-archiving archive for, as Derrida asserts 'the technical structure of the archiving archive also determines the structure of the archivable content even in its very coming into existence and in its relationship to the future' (1998: 17). The building in question was a former Victorian asylum,1 and archival research took place via two distinct sources. The first took the form of protracted negotiations with the former administrator, who had saved assorted documents from oblivion when the modern-day psychiatric hospital closed, by storing ledgers and patient records in a back room of his own home—an archive in waiting. Other materials including confidential X-rays and ward books were left in the unsecured derelict building for anyone to seize upon. As Carolyn Steedman states, 'the archive is made from selected and consciously chosen documentation from the past and also from the mad fragmentations that no one intended to preserve and that just ended up there' (2001: 68).

My second source was the fabric of the building itself, and what was left once many of the decorative features had been ransacked by architectural salvagers, and before it was redeveloped into exclusive gated housing. I pored over the edifice for evidence of inhabitation and function before its archival future vanished, aligning my approach with Haraway’s insistence on 'the embodied nature of all vision' in order to 'reclaim the sensory system that that has been used to signify a leap out of the marked body and into a conquering gaze from nowhere' (1991: 188). Through actuating my embodied gaze, I produced two distinct series of artworks derived from archival traces: photographs documenting found indentations produced by handles and locks on plaster walls at points of transition in corridors and entrance areas, assembled as a bookwork (fig. 1); and fabricated indentations produced through re-enacting aperture and enclosure—two of the confining principles of Victorian psychiatry, captured in stop frame animation (fig. 2).

A further artistic research project in 2014, within another former asylum, entitled Safekeeping (custodia), focused on an archive of wrapped personal possessions or 'fagotti'2 (fig. 4). These fagotti had been surrendered by former patients of the Manicomio della Provincia, Rome, and the research was prompted by experiencing an affective encounter when seeing them for the first time during a residency at the Museo Laboratorio della Mente in Rome. The museum, located on the site of the former manicomio is an educational project founded in 1995 that uses interactive audio-visual installations3 to challenge prejudice and stigma relating to mental illness with the 'promotion of health and refutation of all the forms of discrimination and marginalisation' (Martelli 2010).

In my studio, I replicated a selection of the brown paper bundles, using the same distinctive methods of folding, tying, and labelling used in the asylum. Taking these replicas in my hands I formulated and performed repetitive gestures (such as scratching, compressing, and agitating the parcels) to camera through which I sought to re-enact the asylum's operational systems and procedures. I had understood such institutional systems through my wider archival research in a basement full of ledgers and documents in Rome; the collated testimonies of patients; and conversations with the museum director, Dr Pompeo Martelli, himself a clinical psychiatrist. This method4 compelled me to 'make meaningful interpretations and to develop imaginative insights and discernments in order to shift the register of the artistic research from a semi-fictive account to credible critique of the now discredited Italian psychiatric system' (Bennett 2019: 108-109) resulting in a four-channel audio-visual artwork installed in a darkened exhibition space in the former manicomio (fig. 3). Arlette Farge proposes that through archival research, a ‘new “archive” emerges’ and that as the historian works with and readjusts pre-existing forms 'a different narration of reality' is possible (2013: 62-63). However, she then attempts to distinguish between 'writing history'—the thing that historians do—and the writing of historical novels that, although they may be based in extensive archival research, are 'works of fiction' (2013: 76). She goes on to assert that 'the poet creates, the historian argues' (2013: 95). The inconsistency of her argument is apparent, and warrants the supposition that the novelist, poet, or artist might equally create a 'different narration of reality', through drawing upon archival sources. In making site relational work, with the archive as a constituent part of site, the breadth of forms in which archives may be manifest is reflected in both of the institutional sites above, and my approach in each instance draws upon and reflects the very methods of containment employed in nineteenth-century asylums.

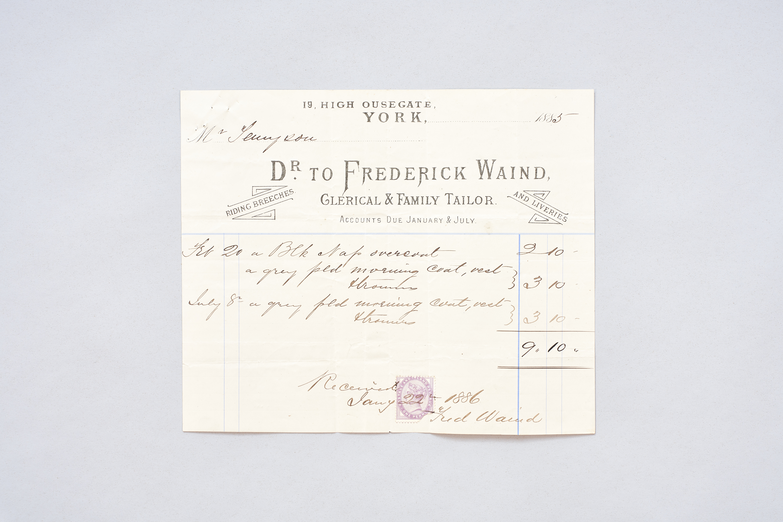

The wrapped paper parcels in Safe-keeping (custodia), reappear in the form of a new artwork in Bummock: Tennyson Research Centre, entitled 'Touch me' (2021) with reference to Edward Tennyson. Unlike the Italian asylums in which patients wore institutional uniforms, in the English system private patients normally kept and wore their own clothes and therefore replacements needed to be procured. The brown paper parcel, then, refers to the wrapped parcels of clothing delivered from the York outfitters to Lime Tree House, the private 'mad house' where Edward lived and was cared for. Hundreds of thorns cover the brown paper, running diagonally across, over, and underneath the parcel, giving rise to what I term an agitated object, or objet agité.5 The thorns refer tangentially to Datura stramonium (part of the Solanceae family), also known as Thorn Apple or Jimson Weed, which was used as a medicinal ingredient in the nineteenth century for its therapeutic effects in cases of mania and convulsions, and for its psychoactive properties6. Another alkaloid found in the Datura genus is hyoscyamine, which is used as an anti-spasmodic and a sedative for schizophrenic patients in modern medicine. It is one component in a portrait of Edward Tennyson entitled Plant Seizure: Edward Tennyson (see fig. 9 below), hanging at a distance in the exhibition from 'Touch Me,' which sits alone on a glass shelf in a solitary vitrine, with the thorns reflected in the glass above and below (fig. 8).

I have previously worked with several archives and collections, including The International Anthony Burgess Foundation, Nottingham Castle, the Media Archive for Central England, and The Lace Archive in Nottingham (as part of the first Bummock project). I would like to focus here on the project Finding the Value (fig. 1), where I worked with the connected field of art collections. My primary research interest is centred on the use of historical paintings by contemporary artists; working with the Madsen Bequest to York Art Gallery allowed for innovative ways to work directly with a museum's collection.

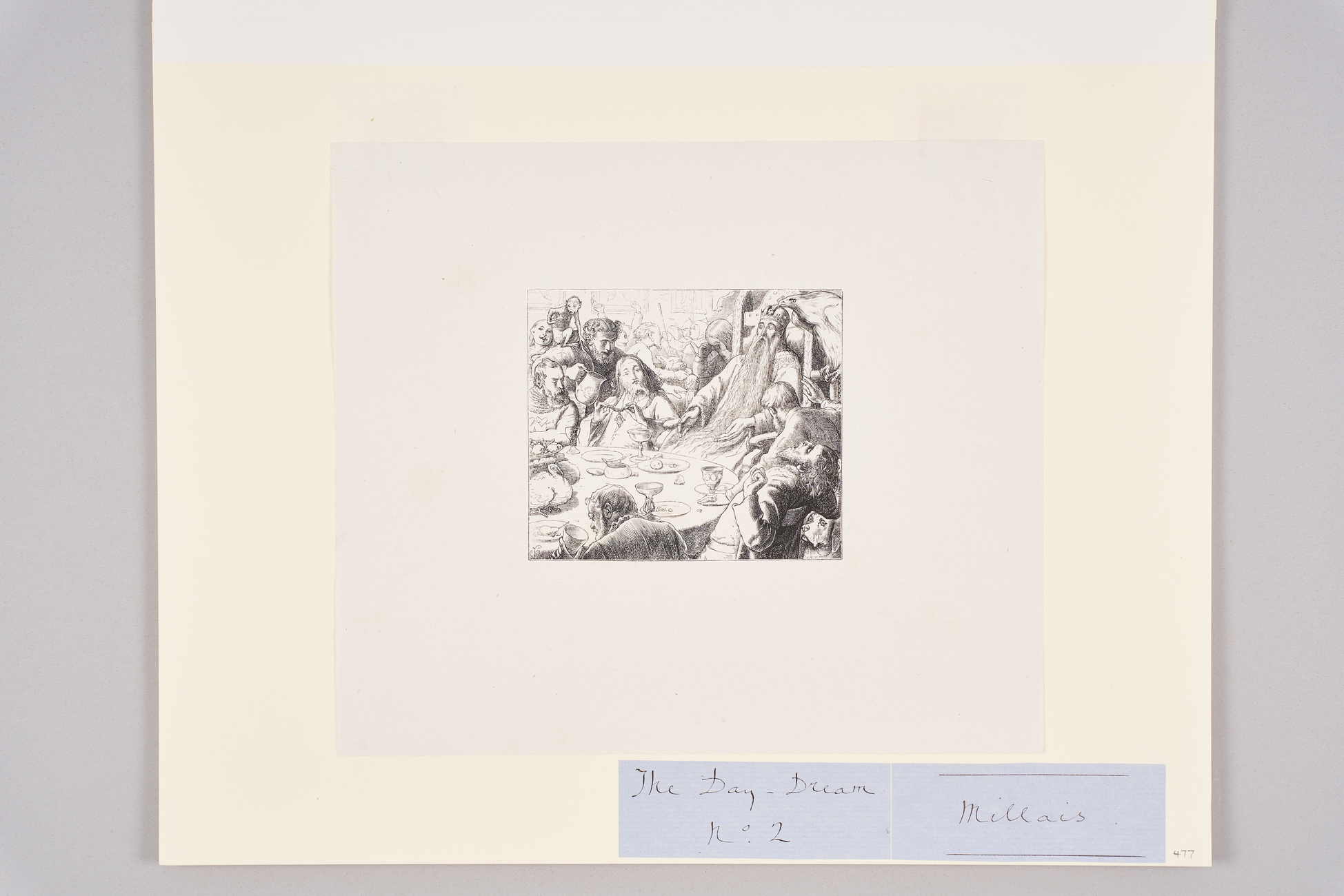

Peter and Karen Madsen bequeathed two million pounds and a wide-ranging art collection to York Art Gallery in 2011. The gift came with no strings attached, with very few items entering the gallery's collection and many items being sold at auction. There remained a fairly large number of lesser value items, both in terms of monetary and artistic worth. As no records were left behind from the Madsen siblings these may have been objects with personal meaning or affection to them. The curators decided that artists would select items from the collection to use as material for new artworks. It was anticipated that these new artworks would promote, in the museum's (then) director Janet Barnes words: 'a creative questioning of, and experiment in, the inheritance and development of cultural values. For a past generosity should not be simply cashed in against the vagaries of a present fashion. The present must actively inherit the past otherwise we will sell short the future' (2014: 3).

I chose a selection of thirty-eight paintings and prints from the Madsen Collection with which to create new works (fig. 3). I wanted to reflect the eclectic nature of Peter Madsen's collected habits and included many different subjects, mediums, genres, and geographic and cultural ranges. My ReconFigure Paintings series developed from this project features an abstract painted structure superimposed upon the human figures in the paintings (figs. 2 and 4).

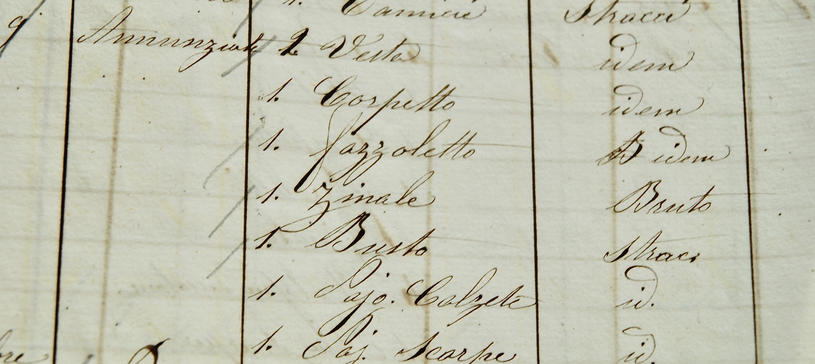

Sheltered under the glass dome of the Lincoln City Library, the distinctly informal layout and management of the Tennyson Research Centre (TRC) was somewhat beguiling at first encounter. The archival accoutrements associated with safeguarding rare, fragile, and antiquated holdings were noticeably absent, yet they appeared in abundance once the TRC was moved to the nearby Lincolnshire Archives twelve months later. I had encountered such accessories—notably the foam supports used to bear the weight of old tomes when accessing the damaged registers containing the lists of patients' belongings in Rome (fig. 5 above). Each ledger was nestled on firm yet yielding spongey wedges, while the friable pages were held open by a snake weight—a metre-long serpentine of lead beads encased in acid free cotton that gently flattened the paper without undue pressure.

The installation Bound (2020) draws directly on the function of the archival paraphernalia, notably the foam wedges and snake weights, but employs them in abundance in order to emphasise the necessary protocols that accompany a visit to an archive. In Bound, a copy of Alfred, Lord Tennyson's blank verse poem The Princess is placed on each of five grey foam plinths. The books lie open, each double page flattened by an excess of snake weights running from left to right and right to left, echoing the lines of text (figs. 6 and 7). Only selected passages of the poem are legible between the snake weights, spoken by five different characters—Princess Ida, her father Gama, the Prince, and his friend Cyril. The fifth character is Lilia who is central to the prologue and conclusion. Her father is Sir Walter Vivian, owner of the estate where she is gathered with her brother and six of his friends, and the prologue opens with the young men reminiscing about college life during a recreational picnic. In response, Lilia enthusiastically advocates for women's intellectual potential but remarks that 'convention beats them down' (Tennyson 1847: 6), and she then introduces the idea of a women-only college, a storyline that is taken up by the seven male friends, with each telling a portion of the narrative in turn.

Alfred had been maligned by his contemporaries for avoiding intellectual themes in his poetry, and he is said to have written The Princess following a conversation with his future wife, Emily Selwood7 about the lack of access to higher education experienced by Victorian women.8 First published in 1847,9 the poem's main protagonist, Princess Ida, has established a women-only college and confidently asserts her desire to pursue purely educational aspirations rather than accept marriage to the prince, to whom she was betrothed in childhood. However, by the end of the overly complex narrative Ida appears to forfeit her desire for education in favour of marriage. The purpose of The Princess baffled Victorian readers and as Tennyson scholar Jim Cheshire writes, 'the tone of the poem is still difficult for modern audiences'. He continues: 'is this a refutation of the idea of women’s education, or a radical liberal statement supporting it?' (2022: 83). In Bound, the intention was to obscure Alfred's confusing and calamitous ending (albeit the tip), and through a close reading to reveal only passages that cast a favourable light on the Princess' pedagogical project (proposed as bummock material), and to bind the text to the contemporary treatises on women's education that were published throughout the latter part of the nineteenth century, such as Marion Reid's A Plea for Women (1843), The Higher Education of Women by Emily Davies (1866), and Women and the Universities by Joshua Girling Fitch (1890). In this way the bummock is highlighted so that the chosen excerpts are elevated in importance—so flipping the bummock. The name of each main character is cut from copied pages from these publications and attached with sewing pins to the plinth, so in addition to the excerpts of text from the poem revealed by the snake weights, fragments of the arguments being made by Reid, Davies, and Fitch for women's higher education are visible (fig. 7).

The three elder Tennyson brothers, Frederick, Charles, and Alfred, all studied at Cambridge10 and Edward, the eldest of Alfred's four younger brothers was to follow, but by 1833 his mental state had deteriorated to such an extent that he was sent to 'a home for the insane' in York, as he was ‘a present danger to himself and others' (Martin 1980: 137). Edward was subsequently edited out of the family narrative and was not mentioned in Hallam Tennyson’s two volume Alfred Lord Tennyson—A Memoir by His Son (1897)—according to Grace Timmins, Emily and Hallam also destroyed any documents that cast an unfavourable light on Alfred or his family. In the archive the only trace of Edward is a box of vouchers and invoices that record the costs of his care and receipts for purchases of shirts, collars, morning suits, footwear, and undergarments from three gentlemen's outfitters in York, paid for by a trust fund set up by his grandfather. Edward died in York, England fifty-seven years later, and there is no evidence that any of his family ever visited him. Robert Martin's biography of Tennyson, The Unquiet Heart of 1980, shed light for the first time on the bouts of mental illness experienced by all the male Tennysons including nervous anxiety, addiction, depression, and in Alfred's case—hypochondria—and at least three of them experienced cataleptic11 seizures.

The archive holds a few examples of commemorative chinaware relating to Alfred, Lord Tennyson and in 1997 Royal Doulton produced a complete dinner service named 'Tennyson' displaying flourishes of decorative foliage on a rich plum background with gold edging, suggesting both opulence and gentility. The Tennyson family dinner table in the Rectory at Somersby, where Alfred and his ten living siblings spent their childhood years, was neither genteel nor affluent. According to Martin (1980) there were many disruptions to family life caused by their father, George Clayton Tennyson, whose erratic behaviour and poor physical and mental health led to regular feuds with his own father, George Tennyson 'The Old Man of the Wolds'. The family was frequently impoverished because, despite being the younger brother, Alfred's uncle was heir to the family wealth. The Tennysons' mother, Elizabeth (née Fytche), was affectionate and a constant source of comfort (see from Comforter 2021, fig. 10 to the left) to the children whose poems she listened to tirelessly, such that she 'offset her husband’s nervous sternness to the children' (Martin 1980: 18). Nonetheless, she was something of an eccentric and wholly unconventional in her manners, so the Tennyson brothers and sisters grew up without understanding the 'normal modes of social behaviour'12 (Martin 1980: 18). However, it appears that the family benefitted greatly from 'art and learning' being considered quite normal activities by both parents. The library held 2,500 books covering a wide range of scholarly titles and subjects, and the dinner table at the rectory was probably a lively and emotionally warm, if chaotic setting, with poetry being a shared concern among the older brothers while Elizabeth Tennyson's pet monkey Billy rampaged about (Martin 1980: 18-19).

Early in the Bummock project I planned to incorporate the Tennyson traits, tendencies, and neuroses into the design of a new dinner set to capture the unconventional spirit of the Tennyson family, its complexities, its tensions, and diagnoses. However, that idea was redirected into a series of drawings entitled Plant Seizure (2020) comprising composite layered drawings based on plants used in the nineteenth-century relating to the remedies and addictions associated with the male Tennysons' various ailments and conditions, and the women on whose support they depended. Each Plant Seizures portrays a specific member of the Tennyson family and includes stylised drawings of plants or items significant to that individual's emotional life, or their presumed ailments (fig. 9). These are to be translated into a design for porcelain tableware to commemorate the less well-known aspects of Tennyson and his close relatives. Additionally, the plants are being developed into drawings on paper patterns, emulating those in Audrey Tennyson's collection of collar patterns.

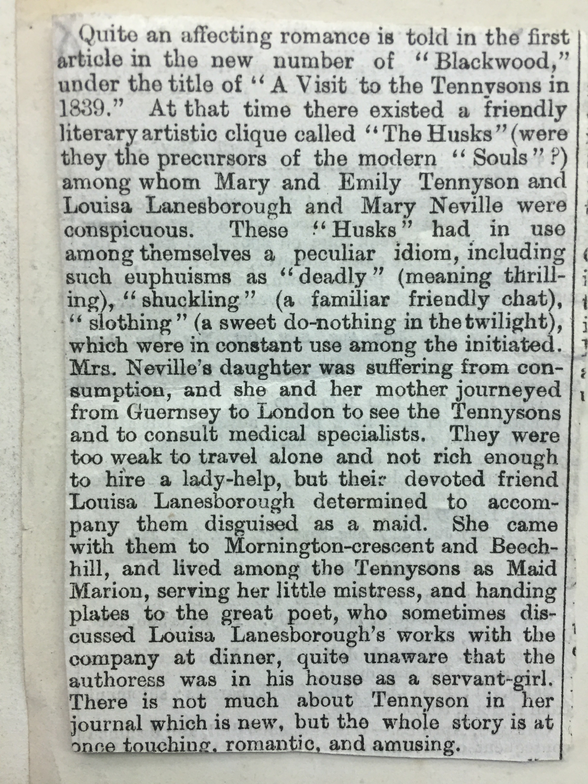

In preparing the text for this exposition, I returned to the first of my two Bummock: Tennyson Research Centre sketchbooks, and to some photos taken at the TRC that I had left behind. In doing so, I found a newspaper clipping from Arthur Tennyson’s sketchbook about 'The Husks'—a 'friendly literary artistic clique [...] among whom Mary and Emily Tennyson [...] were conspicuous'. A husk being the discarded outer covering of a nut or seed might suggest the choice of this term as a metaphor for the situation of Tennyson's sisters and their friends who, as Victorian women, were unable to attend university, yet were talented and capable of writing poetry. This links to the concerns in my artwork 'The Princess', and a related bummock draws me towards it, again.

It is believed that the Finding the Value project was the first time that a museum had commissioned new artworks to be created permanently from works in their care. The questioning of value that was the curatorial thrust came with a responsibility. The hypothesis was that contemporary artists could add (financial and/or artistic) value to these overlooked and undervalued items. There is a strong connection here to the ethos of the Bummock project: these items were certainly not the tip of the Madsen Collection.

A significant difference is that with Finding the Value, the artworks I painted over could not go back to their original state. The value we placed on the original objects in the present was irrevocably changed with the original artworks being deemed valuable only in as much as becoming material for me to use as an artist. My hesitation at times to work with the original materials and the 'harm' I might do to the works was tempered by the encouragement of museum staff, the excitement of the opportunity to work with artworks in this way, to be supported, and indeed encouraged by the museum. The experience on this project directly led to the collaborative Bummock project that forms the basis for this current exposition.

My research focus for the project was born from spending time paying attention to what was physically in the archive and to what the archivist could direct me towards through her embodied knowledge. Curator Vytautas Michelkevičius writes that 'method determination in artistic research often happens in reverse order. Naturally, this also depends on the difficulties artists encounter in trying to formulate a research hypothesis, as their knowledge is embodied in materials and processes, and thus difficult to put in words' (2018: 144-145). The controlled rummage centres on a reverse order approach to accessing the archive, something done by feeling the way, testing and gauging results through doing.

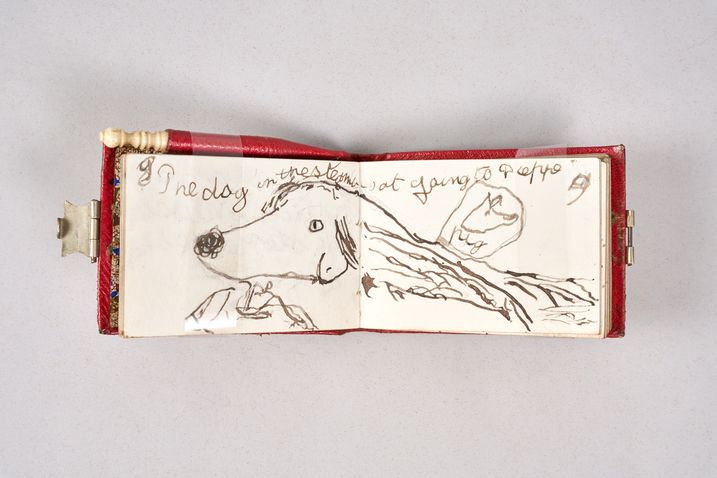

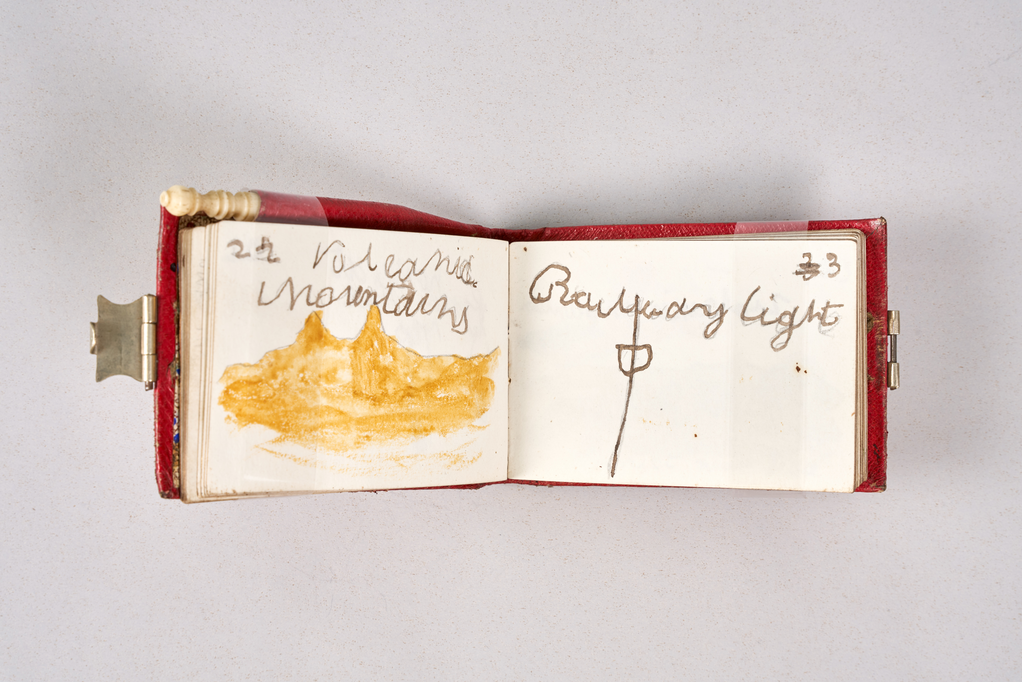

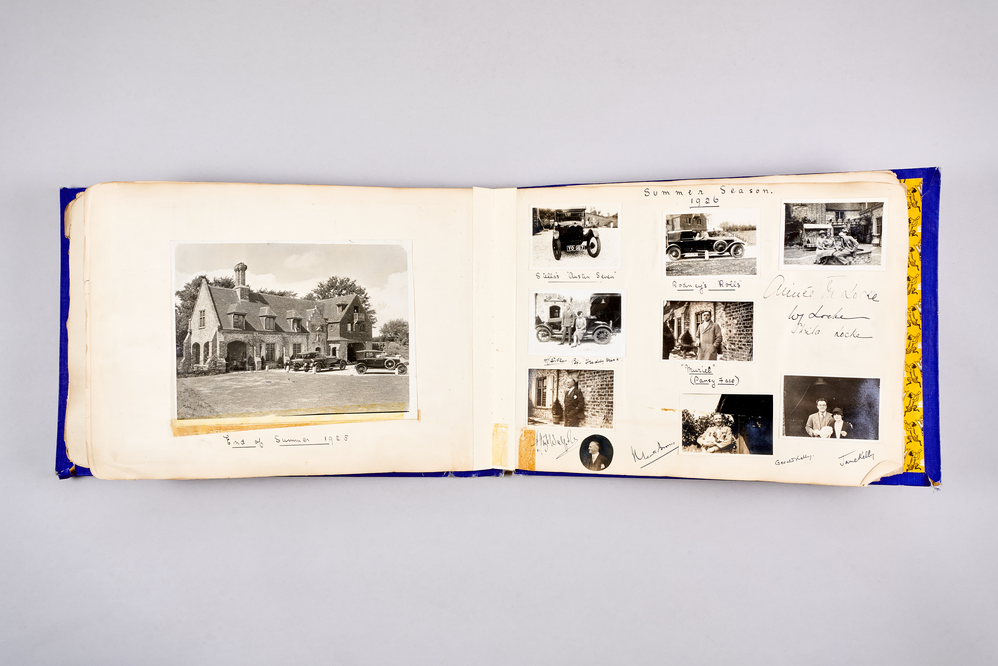

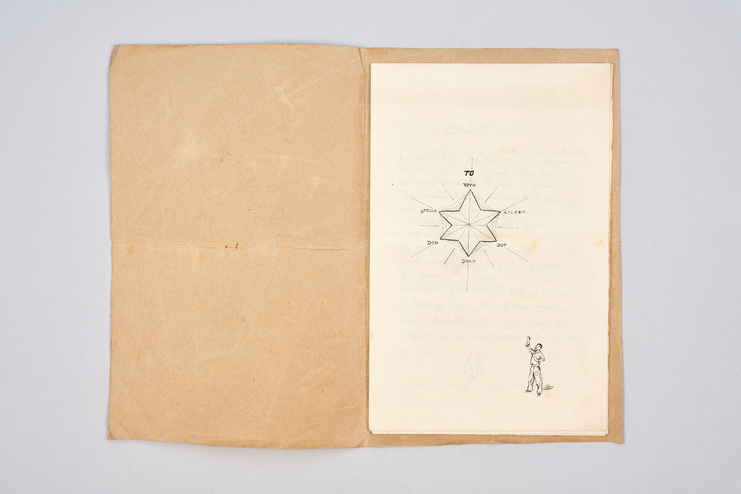

From scoping visits, I was most drawn to two things—Alfred's drawings in the margins of drafts of his poems and items relating to the children of Emily and Alfred Tennyson. A significant aspect of the TRC is the wealth of materials related to family members. As Sue Breakell points out: 'The TRC archives remind us that any person notable enough to have their archives brought into a collecting institution doesn't exist in isolation: they bring with them their childhood and family context, a context to the archive as well as to the individual. Friends, family members and associates are caught up in the archives' (2022: 69). Subsequent secondary research and archive visits uncovered Hallam Tennyson's two childhood notebooks. Although I continued to rummage for other items and approaches, I knew intuitively that there were no other items that would be of more interest.

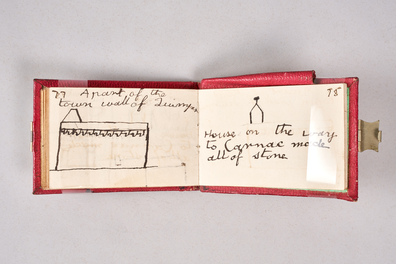

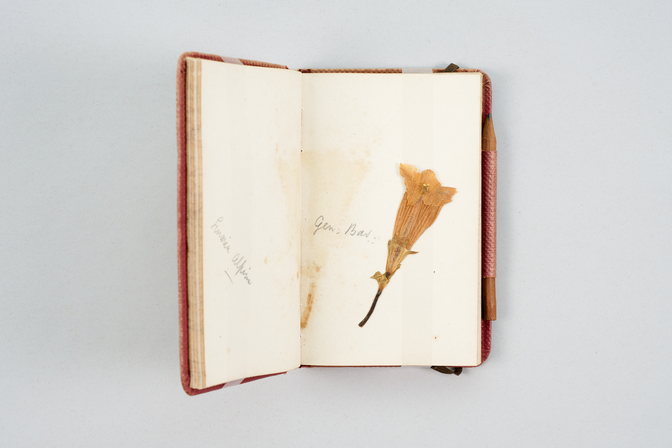

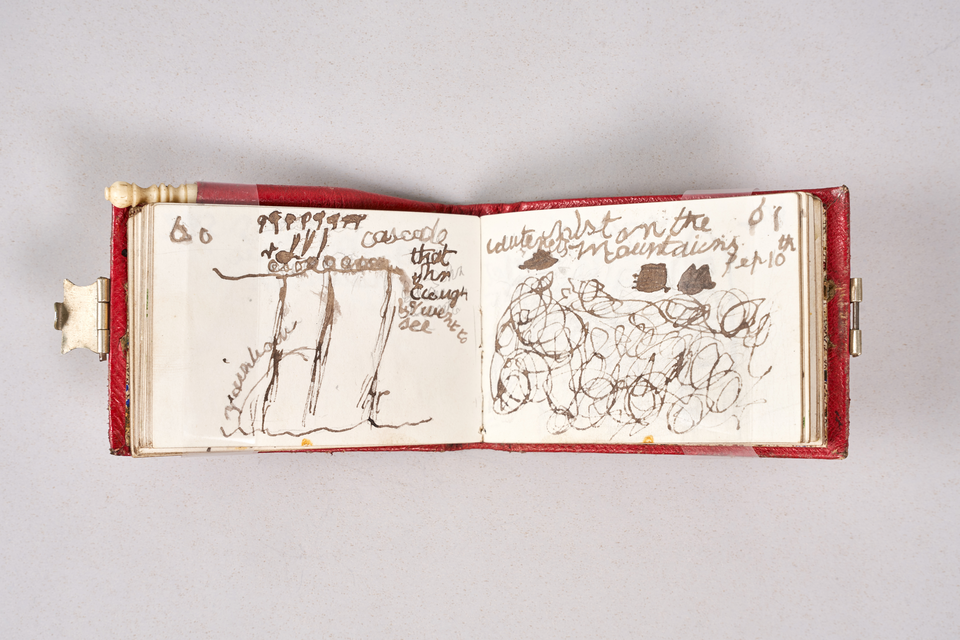

I was initially drawn to the notebooks by the compelling nature of their minute size. Presumably, the size was practical as the content indicates that Hallam travelled with the book. Susan Stewart talks of how from the very start,13 miniature books 'speak of infinite time, of the time of labor, lost in its multiplicity, and of the time of the world, collapsed within a minimum of physical space' (1992: 39). I found these sentiments to ring true within the minute pages of Hallam's notebook, which included observational drawings; chess, maths and geometry problems; holiday notes; handwriting practice; and more—a collapsed and compressed microcosm of middle-class Victorian childhood. I am confident that I would not have found this item if I had set out to perform catalogue searches based on keywords connected to my research interests.

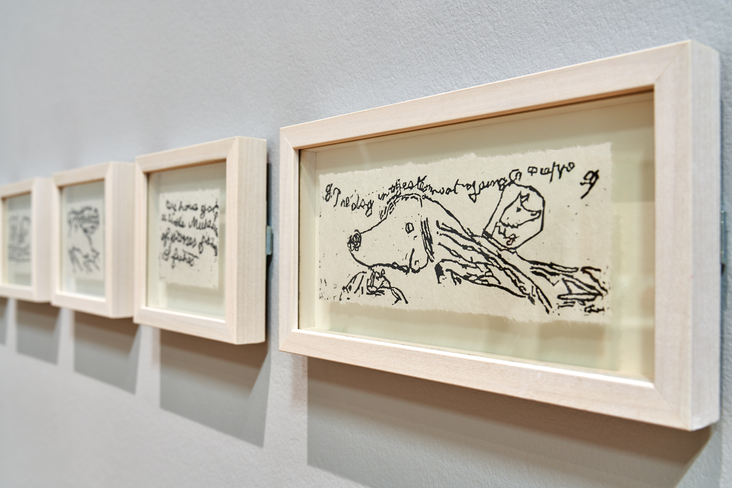

After experimenting with how to translate Hallam's notebooks through artistic practice, I settled on creating woodblock prints (figs. 5 and 8) that replicated selected pages as accurately as possible. The differences14 became the pivot point to create friction among, and thus interest, simultaneously, in the original objects, what they represent, the role of appropriation, and the role of artistic practice in archival research. Hallam's notebooks disclose a child's innate curiosity in so many things that can be side-lined as we become adults. For me, bringing out Hallam's notebook into the world to be seen publicly, was significant in the project, both in the actual notebooks and my woodblock transcriptions (figs. 7 and 9). This enabled Hallam's 'voice', and (Victorian) children more widely, to be shared and valued as important; it is indicative of a shifting value set that can be borne out by looking to the 'bummock' rather than the 'tip'.

We enter the archive together—Sarah, Danica, and I—and this strikes me as significant. Our research journey is one of being 'alone/together' that allows for a sharing of what is discovered individually. When I discovered the tiny notebooks by the pre-teen Hallam Tennyson (fig. 6) in the archive (Council, n.d.) there was an immediate and clear potential, both for creating artworks and wider research significance. This was felt intuitively, rather than being propositionally, known (Moser 1987). The discoveries made individually were shared and their (potential) significance (or not) was tested in tandem with the other two artists.

I would frequently think about what Sarah or Danica would be probing, saying, or questioning about what I was doing, as I noted in our reflective recorded conversation: 'So that shared-ness, is there when you're on your own as well. And that's a kind of resonant thing with me, that by bringing in others to your singular thought pattern is so beneficial as working through the process' (Bennett, Bracey and Maier 2021). My individual decisions within the research process, always felt like they were being enacted with a sense of 'being with' the other two artists, whether they were physically present or not. There is a sense of 'wit(h)nessing' that was both actively and subconsciously utilised during the research process, to enable us to be more attentive to the archival material and the process of creating artworks.15 It is this use of wit(h)nessing that is pertinent here; 'Wit(h)nessing is an enabling activity then, for re-activating heightened states of alertness, vigilance and receptivity; in turn, related to the event of noticing' (Gansterer and others 2017: 164).

The collaborative ethos of working with others in an individual space is evocative of toddlers' parallel play; each child will play around others, learning through observation and osmosis, but without overt cooperation and engagement. There is a benefit to working together that is often indirect and intangible. Jean-Luc Nancy states 'being cannot be anything but being-with-one-another, circulating in the with and as the with of this singularly plural existence' (2000: 3). Nancy goes on to discuss how the importance of being 'with' as a way to understand meaning is not a dialectical or propositional one, but that understanding that is shared 'is' the critical thing. The importance of 'with' is in 'the closeness, the brushing up against or the coming across, the almost-there [l'à-peu-près] of distanced proximity' (Nancy 2000: 98).

The 'timbre'16 of the research grew outwards; it was felt between the object and myself initially, then 'bounced off' Danica, Sarah, and Grace Timmins in the archive at the time, and further outwards to other agents—artists, historians, friends, books/articles, etc. A network methodology between the three artists and other agents in the research was intuitively approached, which allowed for what I believe is a 'rebound, as a resonance that builds and is not just a passive one-way process; touchpoints are all about drawing lines "with" and almost being able to kind of trace where things are going and following for patterns' (Bennett, Bracey and Maier 2021). Importantly the touchpoints were with both humans and objects. There is a reciprocity of contact between Bruno Latour’s 'actants'17 and the encounter with the objects in the archive. I found that specifically Hallam’s notebooks had an agency of equivalence and were in 'dialogue with' myself. As Latour states 'we have to accept that the continuity of any course of action will rarely consist of human-to-human connections (for which the basic social skills would be enough anyway) or of object-object connections, but will probably zigzag from one to the other' (Latour 2005: 75). The collaboration was 'with' objects as much as 'with' people, a relationship which can often be side-lined when considering a research process.

I approached the TRC inquisitively, with no expectations of the research focus. There was a productive spirit of ignorance akin to Carlo Ginzberg’s phrase 'euphoria of ignorance' which describes the 'sensation of not knowing anything but being on the verge of beginning to learn something' (2012: 216). I was receptive, rather than being closed, to what might be of potential significance in the archive. Timmins gave pointers towards things that would not necessarily be able to be found through the catalogue search through questions such as 'what has nobody else looked at?' or 'what in her view is the 'bummock' of the archive?'. Calling upon the archivist’s experience, expertise, and knowledge, as well as being able to see and touch the material was deeply beneficial to me as a researcher. Reflecting on the project I believe that the conversations with Timmins guided me to points of eventual research interest and that '[i]n many ways she was the "control" in my unsystematic rummage through the archive' (Bracey and Maier 2022: 126). Thus, information about items that are unlikely to be recorded or found on a catalogue record card or a keyword had more chance of being uncovered with the controlled rummage.

There was a plethora of possibilities for what could be explored in the archive. I did end up creating a series of work directly related to Alfred, Lord Tennyson (fig. 10), as a result of delays caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. These filmed performances to camera18 were based on a story of when his first poetry was published in April 1927, together with (poems by) Alfred's elder brothers Charles and Frederick. On the launch day, Charles and Alfred travelled to Mablethorpe, on the Lincolnshire coast, from their family home in Somersby. Here they celebrated by antiphonally shouting their poems to the sea. In July 2021 I recited selected Tennyson poems along the South Devon coast where I grew up and the next month the same poems were shouted to the sea at Mablethorpe, close to my current home.

Early in the research stage I asked Timmins what she believed was of value in the archive but had not been researched so far. Among other aspects, she spoke of an uncatalogued box of items relating to Alfred and Emily Tennyson's second-born son, Lionel. Although I did not end up using these items, it was being receptive to moments like this when using the controlled rummage approach that led me towards researching the wider family.

Tacit and embodied knowledge drives much of the research process when working in the archive; something sensed, felt, and followed intuitively can be a good approach to uncover things of value, rather than relying on propositional knowledge. Michelkevičius succinctly describes tacit knowledge as the 'things you don't quite know yet, but know you may be able to do, or describe. Tacit knowledge is held in suspension in a medium: it promises that it can be at least partly articulated, extracted from its material, and brought into language'. (2018: 130) I sensed that the children were an underexplored area of research in connection to Alfred, Lord Tennyson. This was confirmed by Grace, who also informed me that no one had requested to view either of the boxes on Lionel in the archive, or Hallam's notebooks that I ended up using.

The approach of foregrounding intuition and finding relations between things can be aligned with Deleuze's notion of 'images of thought', which John Rajchman describes as 'a tacit presupposition of the creation of concepts and their relation to what is yet to come' (2000: 32). Not directly formed around or about ideas, but rather about relations: 'It works from "intuitions" about problems rather than propositions, and is thus akin to what Wittgenstein had in mind in his preference for exposing "pictures" over advancing or disputing arguments, or when he declares "don't think, look!"'(Rajchman 2000: 33). The importance of looking and paying attention to what is physically in the archive and following an intuitive lead is foregrounded in the controlled rummage.

The boxes relating to Lionel remain a 'not yet' aspect of the archive to me. More is known of Hallam Tennyson, primarily through records relating to his time as Governor-General of Australia, his duties in the House of Lords and his first biography of his father. However, comparatively little is known of Lionel, perhaps owing to his early death at the age of thirty-two. To my mind, there is potential here for further research, particularly into the impact on both children of their upbringing and an early example of growing up with a celebrity parent (Boyce, Finnerty, and Millim 2013). Lionel remains a little bit of an enigma and an unknown entity, something that someone, myself or otherwise, might be minded to return to the TRC, to develop further research.

I have worked from historical objects and imagery as sources for new artworks from early on in my artistic career: through found patterns and images sourced from books; objects found in antique and charity shops; working within and from ruins or abandoned sites. It has been a comfortable progression from these more personally sourced or found materials to working within archives and collections.

Initial forays into working with archival spaces (of a sort) came while working as part of an international artists network Topographies of the Obsolete (TotO), led by Bergen Academy of Art and Design.19 This project focused on and was held within the recently abandoned Spode ceramic factory,20 in Stoke-on-Trent, England. While much of the technical equipment had been removed, most of the moulds (new and historical), decals, office equipment, ceramic blanks, offices, paperwork, and personal items were all left in situ when the factory shut down in 2008. Regulated by the City Council, who acquired control of the grounds, building, and contents after Spode folded, it felt a privilege to have almost unrestrained access to the site—as opposed the necessary controlled regulations seen within a formal archive or collection. The Counci's primary concern regarding access to the site was around safety and each visit saw less and less of the site deemed safe for exploration. The council also held control over what objects and items could be removed; however, with permission, I was allowed to remove certain defunct decals. This is vastly different from a formal archive which has close control over what and how one can access items. As archivist and historian Irmgard Christa Becker has noted: 'In an archive there are certain rules which define the open access to the material' (2016: 61).

The TotO project focused on the role of artists in non-art space and the post-industrial site as raw material based on items found within the abandoned Spode factory. During this project I worked with ceramic components and decorative motifs found within the Spode site, creating artworks that engaged with ideas of modulation of value in these found objects (fig. 1) through various assemblages. In the ongoing off-shoot project, Returns, my work explored oppositions within embodied, performative, and formal exploration through constructions that trouble conventional hierarchies of practice and object (fig. 2).

Just prior to the conceptualisation of Bummock I was invited to work with the Collection and Usher Gallery's textile collection and specifically focused on a Jacobean bedspread and the historical sampler collection rarely seen outside archival storage. As there was only a limited number of pieces to work with, it was easy to view, investigate, and engage with them all. I initially accessed the items through a curator's tour of the art store, showing me two to three movable walls that held the textile collection. In addition, a historian’s document involving a printed matrix of each item included an image of the work; details of acquisition; and any known dates, makers' details, and origin location.

The project and concluding exhibition titled Stitch & Peacock (The Collection Museum, Lincoln, England 2014-2015) focused on exploring the line of stitch mimicked through the line of drawing. A series of new drawings and installations were created and shown in collaboration with the archival pieces as a combined installation (fig. 3). My detailed drawings highlighted the relationship between historical and contemporary approaches. The work further extended the value of archives as starting points for creative practice (Lebeter 2013); how artists and designers think about the relationship between traditional hand embroidery, stitching, and drawing; and exploration of innovation through an original interpretation of archival material. Additionally, this research contributes to debates around expanded forms of drawing, textiles, and language.

I was given a week's access within The Collection Museum's art store in which I set up a mini studio next to the historical textile pieces. This was a fruitful speculative time allowing for possibilities, experiments, and ideas to germinate and later grow. After time away from the museum in my studio, I returned with a targeted approach for a further in situ explorative week before the final production of drawings back in my studio. This process of both being in, and away from, the archive worked very well to allow for experimentation without judgement or worry of failure; maturing and development of ideas; evaluation; and then final production of the works.

As part of the overarching Bummock project I undertoook pilot project within the Lace Archive alongside artists Andrew Bracey and Lucy Renton. I developed a series of artistic responses to historical lace drafts—schematic diagrams of machine-made lace. Through redrawing, I examined the method of creating the lace through the imperfections in the drawn line, providing new readings of these historical diagrams. This project took place over the course of a few years working from and in the archive, as well as within the collective and individual studio.

This ongoing interest in working from other source materials is connected to a continued interest with an iterative process of examination through slow looking (Tishman 2018), a desire to study and learn from the source materials. As art historian Slobodan Mijuskovic says in relation to visual artists working with appropriation: 'It appears that a copy simultaneously presupposes and excludes both identity and difference, that it must be, at the same time, identical and different from the original' (Mijuskovic 2009: 142). A rich narrative occurs through this process which adds an embedded depth to the working process and the final works.

I am haunted. Haunted by my past, both recent and distant. Remove the negative connotations one might expect with such a statement and focus instead on the meaning of 'haunt': to frequent, visit regularly, spend time with, be familiar with, indulge in. My past is here with me now, it visits me regularly, a frequent part of my day. By working through the archive and Fyrn’s memories alongside my own I explored this haunting. With a detailed visual memory21, I walk through the past as if I am (almost) there. I can pull the smells and tastes (nearly) into being. My mind thinks, imagines, dreams, and remembers – in multisensory 3-dimensional technicolour – all in the same manner and space. They are distinct yet are only tenuously separate; memories and dreams are sometimes confused.

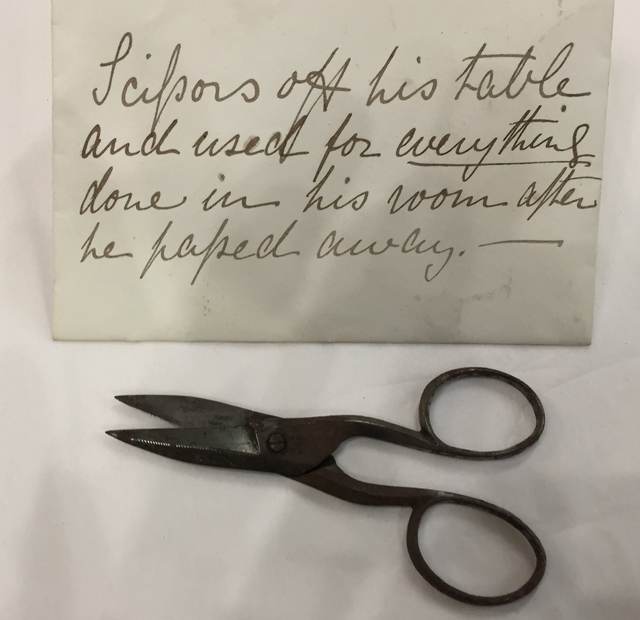

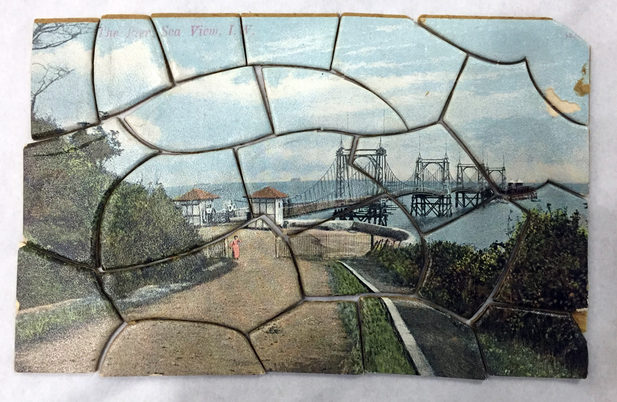

Our personal memories are told and retold – to ourselves and others – slightly differently in each telling; these stories are not set in 'fact' but are in flux. As Jens Brockmeier says: '[…] there is no distinction between remembering and perceiving on a neurological level also holds true with a distinction between perceiving and imagining, as we learn from other studies' (2015: 48). At the core of our memories is a nugget of truth but all too often the stories take on a life of their own. (Re)told stories of reminiscing become their own (new) memory. The remembered "truth" becomes intertwined with the imagined which in turn are interwoven into new narratives. These thoughts specifically permeated into two artworks within the umbrella title Ghost Heirlooms. (fig. 6). Within these works a position of working through (as distinct to from) the archive was taken.

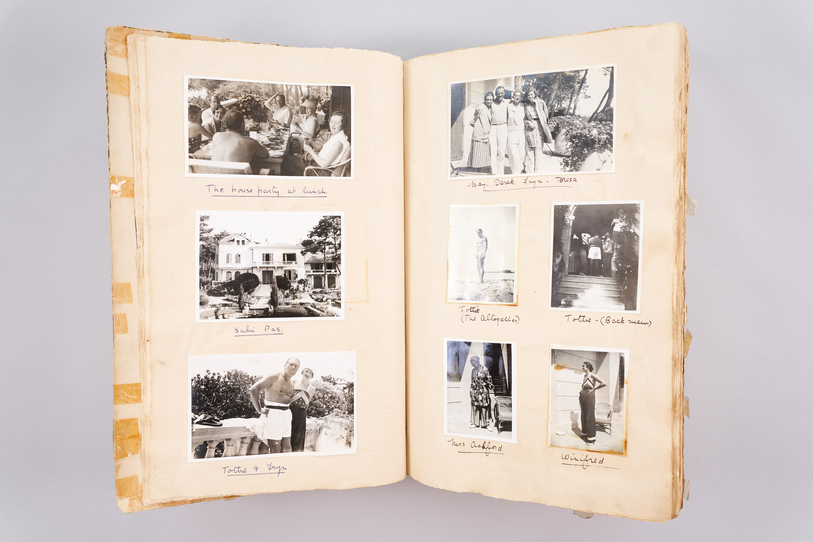

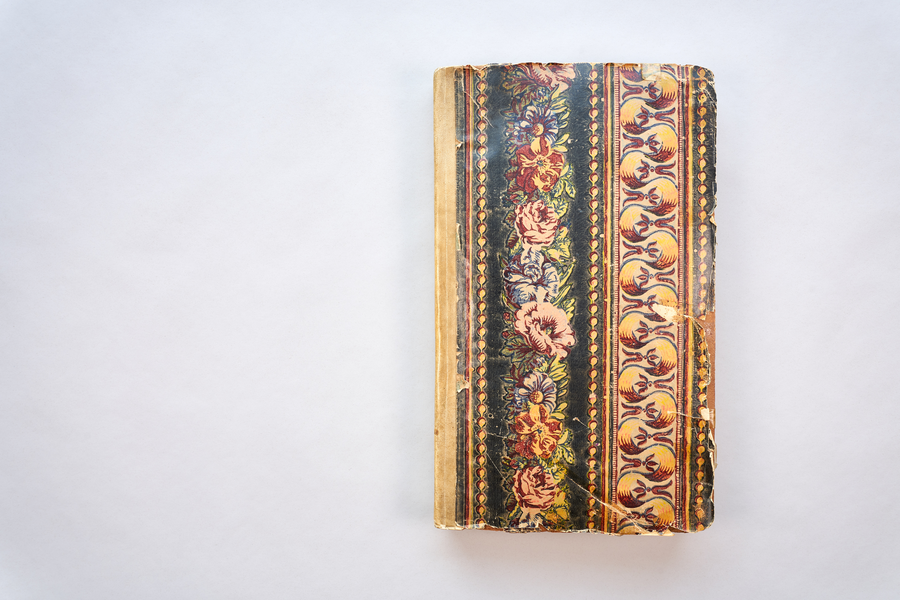

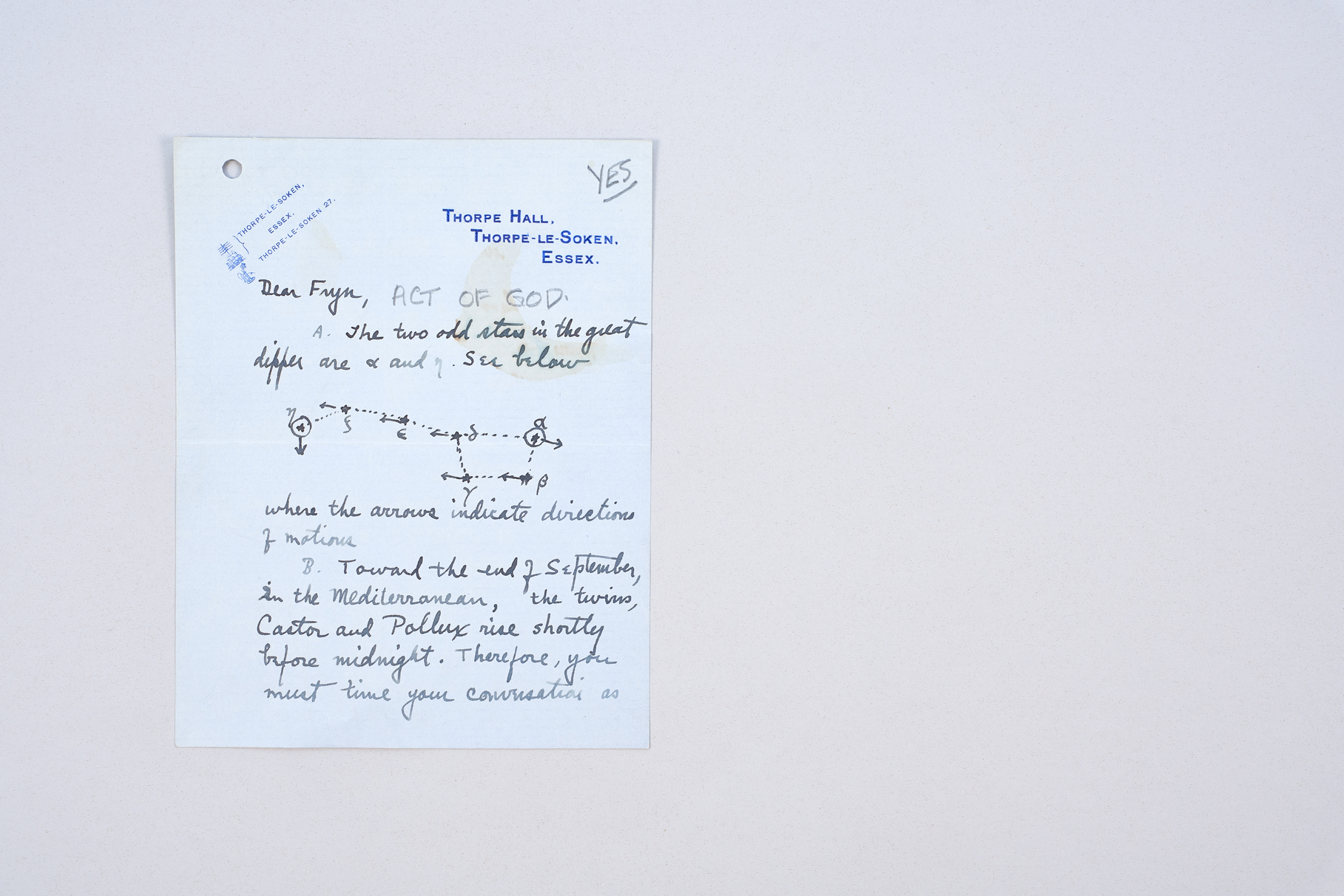

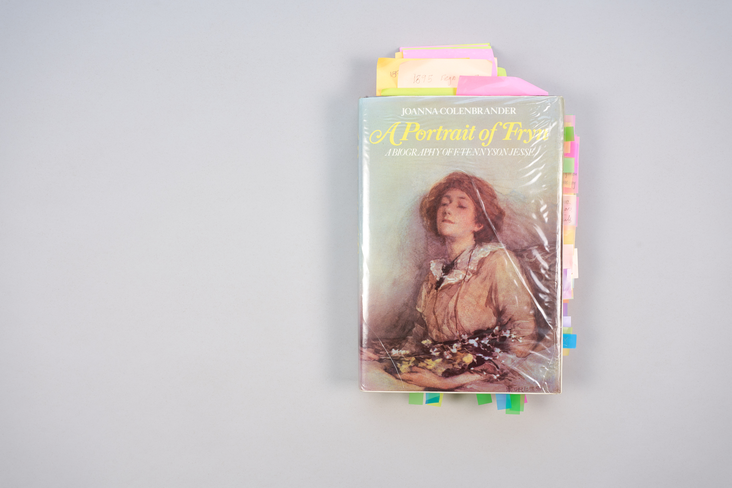

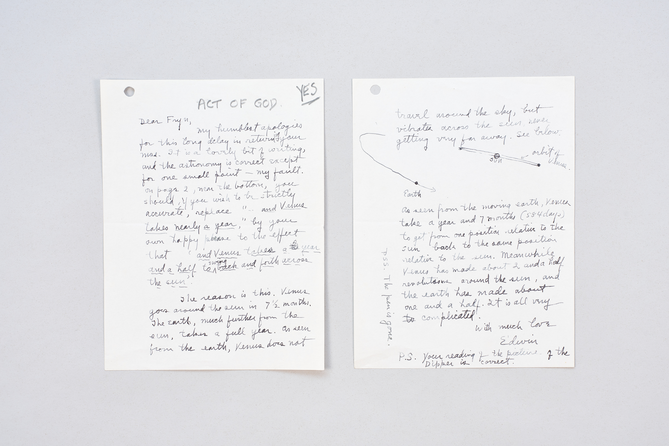

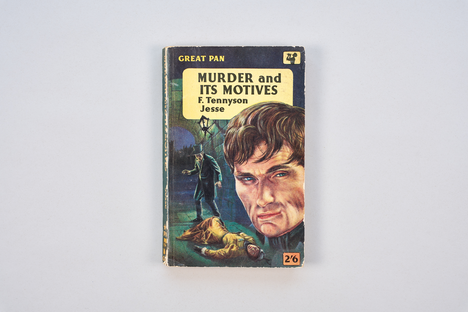

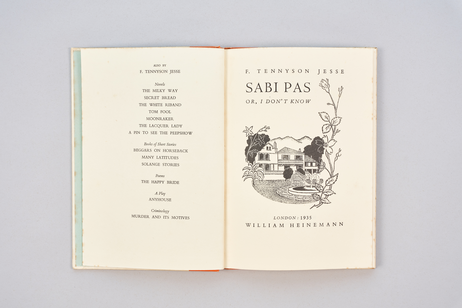

Within the TRC I focused on an individual family member rather than an object. For over five years I was on a journey with Fryn (Wynifried) Tennyson Jesse (1888-1958), the great-niece of Alfred, Lord Tennyson. I was introduced to and was getting to know her (or a version of her) through research within the TRC, her publications, and the bibliography A Portrait of Fryn, by Joanna Colenbrander. I have spent time pondering the imagined and remembered narratives of her life that come through the archived items. There are similarities and cross-overs between Fryn's life and my own; bringing personal and family histories to mind while exploring and researching her narrative. Working from Fryn's archival objects alongside her biography the overarching approach was one of playful interweaving and exploration of memory. The close reading of Fryn's history through the archive and her biography was undertaken in relation to a ‘slow looking’ process of examination. As Shari Tishman states '[slow looking] foregrounds the capacity to observe details, to defer interpretation, to make careful discernments, to shift between different perspectives, to be aware of subjectivity, and to purposefully use a variety of observation strategies in order to move past first impressions.' (2018: 6). This process allowed a considered approach to Fryn's narrative, one that I held with care when developing new artworks.

My initial starting point that led me to Fryn Tennyson Jesse (Fryn) was through discussions with the then archive holder, Grace Timmins. While I continued scoping through the archive it was Fryn who held my attention and, in the end, became the sole focus. This was an interesting and different approach to my usual working method—to explore an individual rather than an image or object. The practical process of research involved an initial survey of Fryn's items within the TRC, followed by an exploration of each of the archive boxes related to her.22 I was permitted special dispensation to retrieve all fourteen boxes of Fryn's part of the archive and spent intensive days within the TRC, as Arlette Farge puts it, 'combing through the archives' (1989: 55) in detail, capturing as much of an overview as I could through notes and photographs.

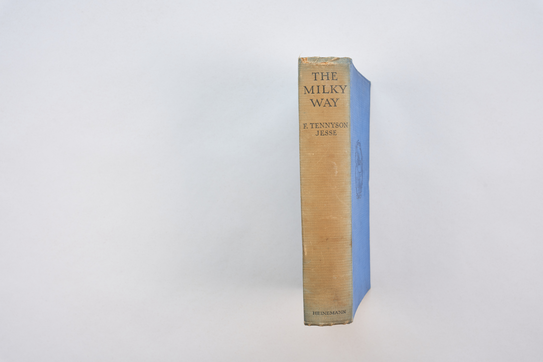

Interestingly, the items related to Fryn were 'donated to the Tennyson Research Centre by Jesse's assistant and biographer Joanna Colenbrander in 1983' (Lincolnshire Archives n.d.). The archival items, personal experience, interviews, and Fryn’s own autobiographies, were part of the source materials for Colenbrander's 1984, A Portrait of Fryn: Biography of F. Tennyson Jesse. I sought out Colenbrander's biography, which became a rich resource for understanding Fryn as a person, and put into context the multitude of objects, including personal and professional letters, news clippings, photographs, scripts, drafts, etc., found within her archived boxes. While I am aware that Colenbrander's biography gives a subjective perspective, I found it became an accessible narrative bringing to life the boxes of archival material held in the TRC on Fryn. Additionally, I felt it important to understand Fryn's writing and published work, so I tracked down and purchased a few of her own publications via eBay. Seeing, holding, and reading these 'well used' books gave me a more embedded insight into Fryn and her writing.

'How do we remember?' and 'how do I remember?', became pertinent considerations. As Fryn states on the title page of her 1919 book The Sword of Deborah (full and free access here https://www.gutenberg.org/files/33906/33906-h/33906-h.htm) on the British Women’s Army in France 'and how should we remember if we have never known?' (Jesse 1919). Through the research, I have imagined Fryn's life stories and remembered my own. This exploration has seen our narratives become intertwined and developed into artworks that hold both our histories (fig. 4). The similarities between imagined and remembered stories has been a key focus; playfully exploring her memories to inhabit them, to understand them, to know them. Exploring her stories until they become as if my own. Playing with them as they intertwine with my own narratives; until I inhabit her memories and imagine mine (Brockmeier 2015). All the works developed for the exhibition could be seen in a form of portrait, biography, or narrative object (commemoration, memorial, tribute) (fig. 5) to both Fryn and my own family history.

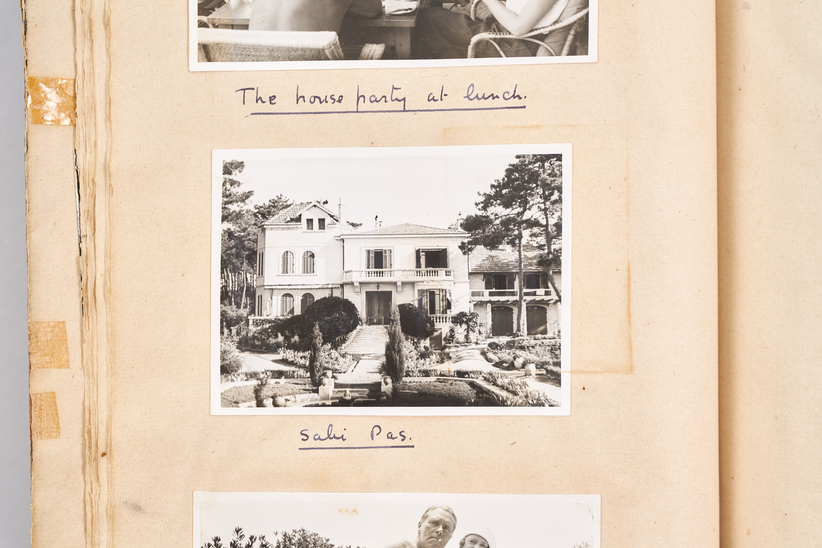

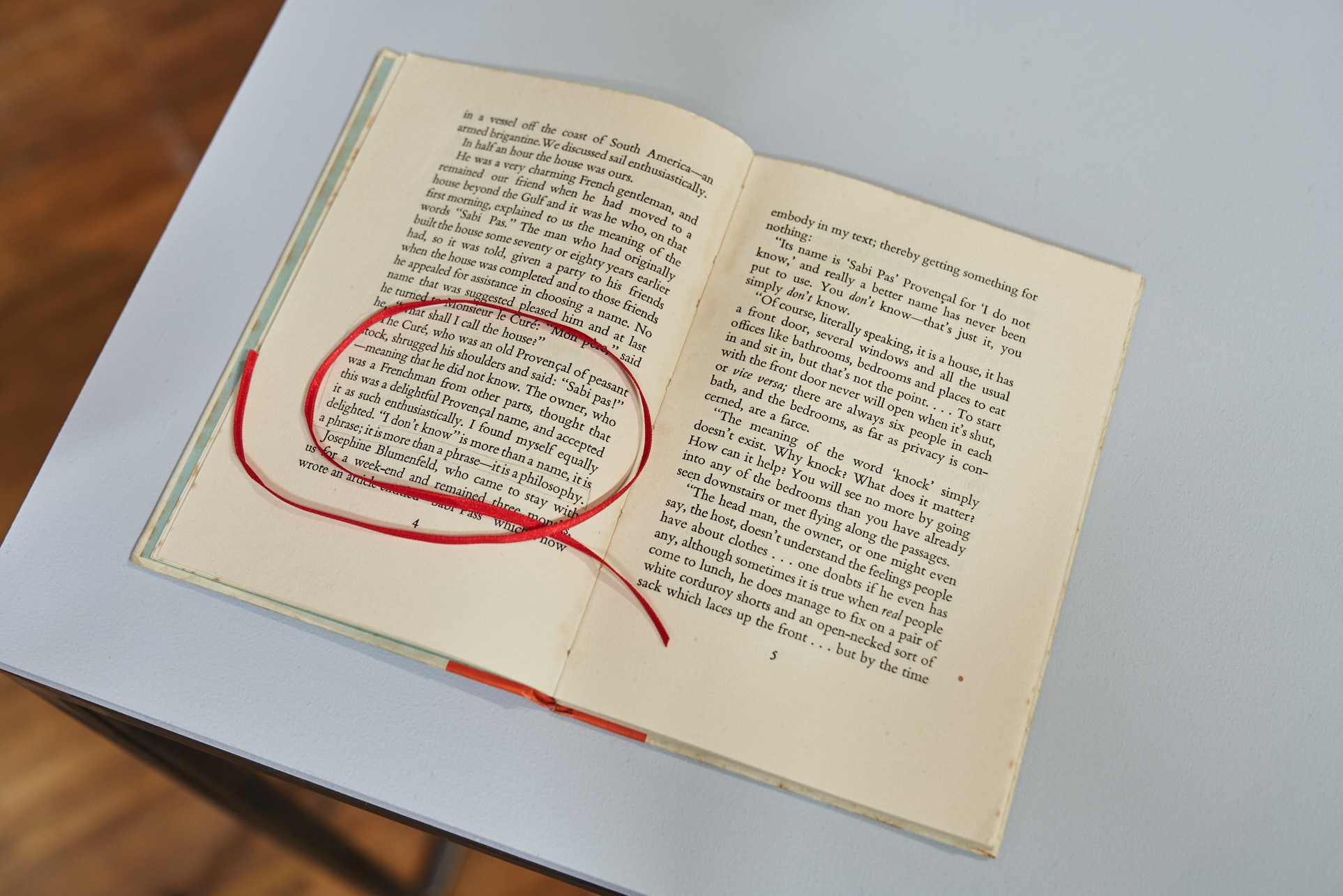

There were many initial thoughts that occurred while undertaking the artistic research that could have been developed into final works. Through time and distance, many of these thoughts matured, mutated, and were subsequently folded into other ideas—thereby becoming part of the final works created. The starting point is a full and unedited immersion in the materials, objects, as well as the numerous thoughts and ideas that come from an overview exploration. During this early stage it was important not to critically evaluate and dismiss ideas and possibilities too soon; it is important to remain open. With this in mind I find a kinship with Fryn's home named 'Sabi Pas' which means 'I don't know' in provincial French (see text in fig. 7).

As Rachel Jones discusses, it is important to 'work without knowing where one is going or might end up [as] a condition of creation' (2013: 16), thereby, allowing a process of development to happen by not judging and dismissing too quickly. Ideas or preliminary sketches that don't end up being produced as final outcomes are still a vital part of the process of development or 'period of incubation, during which ideas churn around below the threshold of consciousness' (Csikszentmihalyi 2013: 79). These initial propositions influenced the wider approach and are found within aspects and details within the final works. They are still there—perhaps like a ghost—found within the final works.

This conclusion has been arrived at in keeping with the spirit of the project, through critical and reflective discussion among the three artists involved. Specifically, we recorded a discussion near the end of the making period of the project and before the exhibition of works at The Collection Museum, Lincoln, England. This discussion was centred around pre-defined topics and areas that enabled us each to prepare through reflecting back on our individual experiences, while also allowing for a spontaneous and responsive approach through the conversation format. This discussion was transcribed, reviewed, and analysed in the process of writing this exposition. This process furthermore informed the individual responses in the 'flipping the bummock' section of the exposition, as well as defining the thrust of our findings for this conclusion.

We have grouped the findings into questions to clearly articulate key focal points. Given the nature of the project and most artistic research, these questions give a necessarily focused account of the project amid the richness of diverse findings, to highlight which is most appropriate for this exposition. These written results are supplemented in the conclusion with a film that contextualises the project and further adds to our individual reflections; a timeline to share our process concisely across the project; and three slideshows of images that document our individual artworks.

The process and learning encountered have allowed for key aspects to percolate from the specificity of the Bummock project, emerging as concepts to be used by other artists, archives, and other archive users and researchers. These concepts are offered as methods and areas of attention for archives, archivists, and artists (and indeed other archive users) for future projects that can take the controlled rummage approach as a way of working with content in the archive.

A central research question for the Bummock project concerns the benefits of the controlled rummage method. In the TRC our controlled rummage was facilitated through bypassing the catalogue. Here the archive holder, Grace Timmins, is a significant agent in providing a whole level of information and linkages that shed light on material unlikely to be recorded on a catalogue record card, digital entry, or found through a keyword search—as material is often found in standard archival research practice. Her answers to our questions not only directed us towards entry points for our controlled rummage approach but also supplemented our delving in the archive, with contextual data and observations. Art historian and Bummock project co-investigator Dr Sian Vaughan has talked from the position of the archivist of the benefits and opportunities of mutual trust and collaboration with artists:

'Perhaps rather than seeing the professional archival activity hierarchically as a precursor to any creative engagement, we could be more open to collaboration and representation throughout the process and question the implied assumption that artists would necessarily corrupt cataloguing through their engagement with the archive. We could recognize the potential of inviting the artist as an insider-outsider, not just positioning them as an outsider to the professional archival process.' (2016: 227)

In effect, the TRC was chosen for this iteration of the Bummock project because it was accessible through a trusted relationship that had been formed with Grace, a circumstance that is not necessarily always repeatable, but establishing some level of trust between the archivist and the researcher is key to the controlled rummage method and ensuring respect for the archival holdings.

The term gatekeeper often arises in connection to archives. For example, the archivist can be referred to as a gatekeeper, as can those who donate materials or set up an archive, as well as the individuals assigned to write the catalogue entries for archival items. An archive itself can be seen as a gatekeeper to what knowledge is kept from the past or for the future. Both 'tip' and 'bummock' items in an archive could also be formed by different types and forms of gatekeepers, which can be extended to include users becoming part of the decision process as to what is worthwhile or not. During Bummock: Tennyson Research Centre we were minded to consider how an archival gatekeeper position can be present before an archive is even made. After Alfred, Lord Tennyson's death, many items relating to him were 'culled' by his wife Emily and son Hallam acting as censors to present and preserve a favourable image of the Poet Laureate, to the world. An awareness of how an archive is created, managed, and used can often be hidden from view, but by considering how to work with or around the gatekeeping constraints one can unlock areas of interest.

In the early stages of Bummock: Tennyson Research Centre we acknowledged that while we experienced a sense of being transgressive in avoiding the archive's tip, our rummaging was nonetheless given a respectful slant by prepending 'rummage' with the adjective 'controlled' thereby ensuring a level of respect for the archive.23 We were not just rummaging as if we were in a flea market, but in a way where the care demanded of the archive was married with the strong potential of chance.24 Poet Susan Howe discusses how creatives can be particularly attuned to the benefits of chance encounters in archives: 'a Things-in-themselves and things-as-they-are-for-us. Often by chance, via out-of-way card catalogues, or through previous web surfing, a particular 'deep' text, or a simple object (bobbin, sampler, scrap of lace) reveals itself here at the surface of the visible, by mystic documentary telepathy' (2020: 18). In other words, the direct encounter in the archive, as opposed to the usual catalogue search, allows other things to come to the surface and to be noticed, this archival trawl rather than the predetermined itinerary is the generative encounter with the unknown.

We also imagined that we were circumventing the enticement of a predetermined search. However, gradually we became aware that despite each of us having no pre-existing knowledge of, or particular interest in Alfred, Lord Tennyson and his oeuvre, we individually found source material that resonated with our extant tendencies towards certain subject matter and expertise in relation to that subject matter. We referred to this as the 'spin of the subjective' (Bennett, Bracey, and Maier 2021). In Bracey's case this was childhood, for Maier it was female biography, and for Bennett it was Victorian psychiatry. All these themes opened up interpretations that are relevant to a contemporary audience, whether it was about children's emotional lives and their understanding of the world, about attitudes to mental illness, or how a woman forges a career through adversity.25 In the Allure of the Archives, Farge suggests that in the historian's journey through archives they do not write history for history’s sake but seek to bring that history into relationship with the present in order to 'bring about "exchange among the living"' (de Certeau cited by Farge 2013: 124). Farge also contends that the historian makes possible a new narration of reality, and that 'a new form of knowledge takes shape' (2013: 64)—a position that as artists, we recognised in the artistic outcomes emerging from our controlled rummage method.

By bringing prominence to the bummock aspects of the TRC through the production and display of new contemporary artworks in relation to the lesser-known family, the potential for flipping the bummock was realised by exhibiting unseen objects from the TRC and providing insights into lessor and unknown members of the wider Tennyson family. Bennett did work with items categorised as belonging to the tip, such as Tennyson’s tobacco or his poetry, but her approach was mediated through the lens of the female Tennysons' obscurity and drew upon lesser-known narratives pertaining to the marginal status the Tennyson women occupied. This is an example of questioning what qualifies as bummock in the archive; for example, do lesser-known aspects of well-known archival items count as a bummock in the archive? We discussed that there is a benefit for the existing research on Alfred, Lord Tennnyson, through a 'transgressive respect' (Bennett, Bracey and Maier 2021) in foregrounding the archival documents and objects relating to the other Tennyson family members. Nonetheless, the objects that form the tip of the TRC such as the original manuscript of In Memoriam A.H.H. (held in a fireproof safe when we first visited the TRC at the Lincoln Library), may inevitably always retain their tip status.

An integral aspect of Bummock: Tennyson Research Centre was to test the benefits of researching simultaneously, or alongside each other in the archive, and during group residencies. While Bummock: Tennyson Research Centre is a joint effort the research undertaken and works created are individual endeavours. With this in mind, we acknowledge the significance of 'collaborative independence' within the project: a term from sociology enabling respect for both the joint endeavour and the individual (Thagaard and Stefansen 2014). Additionally, the extended time period of the project,26 enabled 'wit(h)nessing' as explored through Cocker, Gansterer and Griel’s use of Bracha Ettinger's term in their project, Choreographing Figures (2017: 164-166).27 Both these approaches added a period of close critical attention to our individual research and outcomes, in addition to the opportunity for reflection in the three-way conversation and curating the exhibition. In our conversation, we concurred on the value of acting as touch points for each other to bounce off and identifying common touch points within the archive. Bracey states that 'it is all about drawing lines with and being able to trace where things are going and following patterns and having somebody else to pick them up'. This proximity also served as a generative process creating a cross current of ideas or 'positive infection', as well as critical grounding. We also each felt the 'lingering presence of others and objects informing individual directions' even while working independently in our individual studios (Bennett, Bracey and Maier 2021).

The counterpoint to working closely is the acknowledged risk of becoming our own echo chamber. This was addressed through frequently sharing our work in progress with others in, for example, Summer Lodge at Nottingham Trent University, and various public Bummock events such as the Waddington Art Trail (please see timeline), as well as to our own artistic and academic networks, through seminars, and research presentations.

In sharing the controlled rummage method with other artists and researchers from different disciplines we have had to acknowledge that there are some archives in which the controlled rummage would be more challenging; for example, those that exist only online and have no material or physical counterpart. However, this challenge is something we are considering for future iterations of the larger Bummock project. Such an archive does enable equal access from anywhere in the world as long as a suitable device (phone, iPad, laptop, desktop) is accessible but it may lack the custodianship and insights of an archivist or the ability to access the physical object first-hand.

A more standard model, such as the hybrid archive, has an online catalogue as the first port of call, followed by requests being made for timed access to handle or read selected items, but this requires the researcher to broadly know what they are searching for: a term, a word, a name, a date (a combination of keywords). In this case, access to the archivist would enhance the potential of finding something unexpected, or not previously sought.

The controlled rummage involves access to the archivist(s), a level of trust initially being established, and permission being given to enter the archive at the level of its material holdings, supplemented by the physical proximity to the holdings. Bracey states that when accessing the Lace Archive in the previous iteration of Bummock:

'there is no way that I would have been interested in the ledgers I ended up using if I had not seen them in material form. However, on the shelves in the archive, these beguiling forms of paper immediately captured me and made me want to spend time going through them. This was nothing to do with the content that I would have gleaned from a catalogue description' (Bennett, Bracey and Maier 2021).

The controlled rummage is the fundamental method we have used for accessing archives in our artistic research in two iterations of Bummock, including at the TRC. Through the process of doing the projects, we have developed what the controlled rummage is and can be. We are still in the process of re(de)fining it through future projects in the near future. The reflections on, and analysis of, our learning has led to the clarification of the controlled rummage as a method. During Bummock: Tennyson Research Centre we have identified conditions that constitute the core principles of the controlled rummage, which are set out below.

Bypassing the catalogue: We bypass the traditional ways of accessing the archive's catalogue to utilise alternative ways of accessing and exploring the archive, such as asking questions of the archivist; responding to material, subjective, and aesthetic properties; using chance procedures; or requesting items through alternative descriptor possibilities.

Gatekeepers: We acknowledge that an archive has a multitude of gatekeepers in connection to an archive. We believe that a researcher working in an archive can benefit from being actively aware of who or what a gatekeeper could be, as well as what their role is within the archive. The controlled rummage works best when a relationship of trust is established and maintained with the gatekeepers.

Respect: The controlled part of our rummage is an important recognition of the respect that is integral to archival research, and indeed working with any historical item. An artist could be taken to be an unruly agent; an artist who is left free to rifle or rummage could end in disruption, chaos, and even harm to the archive. We approach with a spirit of respect in the archive that is multiple, encompassing ethical relationships, care, and material considerations. By building up a relationship that aspires towards mutual respect there is a greater likelihood of trust that will allow users to use non-standard ways of accessing and using the archive.

Flipping the bummock: The importance of bringing out the bummock of the archive and showcasing it alongside the artworks created allows for a flip from bummock to tip. We aim to share these under-seen, under-valued, and possibly even uncatalogued items with the wider public, bringing new audiences and awareness of them, thereby allowing them to flip from bummock to tip.

In ascertaining that certain non-standard conditions are favourable to artists when accessing archives, we considered the mutual benefits to archives that artists bring (Lebeter and Smith 2013; Bismarck and others 2002; Lane 2013). The following potential benefits emerged during the research process for Bummock and were the subject of a seminar during the exhibition at The Collection Museum.

Artists can create non-standard connections: For example, Maier strongly related to Fryn Tennyson Jesse's biography through her own personal history. This research-led journey on this lesser-known, but inspirational female Tennyson family member created intertwined and surprising connections in subjects and Maier's artistic outcomes. The research process and outcomes produced see Maier working through the archive rather than directly from the archive.

Artists can bring associative thinking that opens up the archival holdings to new interpretations: Creatives can be particularly attuned to following intuition, being open to chance, and creating connections. Artistic researcher, Lucy Cotter writes that:

'When I think about artists' ways of thinking, I also think about the space to be associative instead of analytical. Certainly, the analysis may come later at some point, but [...] there are different components that don’t necessarily relate to each other even if they appear to.' (2019: 46)28

For example, in Bound Bennett used the paraphernalia of archives—such as snake weights and foam supports—in excess to help highlight feminist concerns within Tennyson's poem, The Princess.

Artists find productive associations between different and/or loosely-related archival items: Although not fully explored in this current iteration of Bummock, something we are acutely aware of when delving in the archive is the surprising, (seemingly) non-logical potential of connecting archival objects. Archivist, Victoria Lane has said that '[t]he physical control of archives is something altogether messier and real which does not simply reflect the model of intellectual controls' (2013: 92). Owing to the pragmatics of space available and the size of items, the catalogue order can be disrupted and non-parallel to the archive itself, with items with no other distinguishing feature than their relative size ending up next to each other. These loosely-related associations between archival items offer great potential in the creation of new artworks, ways of seeing, and navigating the archive anew. Bracey's interest in the childhood notebooks of Hallam Tennyson were largely informed by the enormous variety and rhizomatic nature of the subjects and contents within the miniature pages.

Artists confidently introduce a collage aesthetic: Transferring the principles of collage to mining and working with the archival items allows for multiple and often unexpected connections to be made between aspects of the archive. Art historian Yuval Etgar writes of how collage is a 'preoccupation with the margins, edges or gaps that stop us interpreting the picture as a carrier of information and enables us to see it with fresh eyes. Indeed, the history of collage is implicated in the evolution of the way in which artists employed edges as a potential site of disruptive activity that can criticise, support or accentuate certain aspects of the images bound by them' (2019: 48). This approach of placing images next to each other to shift attention to the periphery or the edge can be extended away from the collage-as-composition towards a tactic to see archival items anew. In the iteration of Bummock: Tennyson Research Centre at The Collection Museum, vitrines of archival objects were paired with artworks created in response. These were treated as, and created, three-dimensional collages in the gallery, with new visual, material, semiotic, and subject possibilities being conjured by their bringing together.

An archive is a rich treasure trove. The increasing move to access through a digital version of the archive is not unexpected and has significant benefits.29 Through artistic research, the Bummock project is seeking to test what might be lost if research within the archive itself is not retained. The driving aims of Bummock are to use the archive 'to create artistic responses in unexpected ways, to generate new readings, knowledge, and artworks. To gain exposure for unseen and/or unvalued parts of archives' (Bracey and Maier, nd). The project is further testing what opportunities and approaches can be brought to standard archival practice if the approach of the artist is utilised.

We have identified, through observation of in-action approaches, significant factors, and methods that artists use to access and work with archival objects that are non-standard compared to usual archival practice. The benefits that artists can bring to an archive and the conditions of the controlled rummage exposed in this conclusion come from learning and knowledge arising through doing. The testing of the controlled rummage method was through a process-driven approach that identified aspects and focuses for future use in the Bummock project, as well as by other archives and artists. A desire for Bummock is to demonstrate the benefit of the controlled rummage and focus on the bummock for other archive users from diverse disciplines and we are excited about how historians, novelists, journalists, and other users might benefit from this alternative approach to accessing an archive.