-

The basse de violon as a solo instrument:

There was very little solo repertoire for the basse de violon. One could imagine that the pieces that descend to Bb' were meant specifically for this instrument, as other instruments lacked such a low register. Still, due to the number of different names for the bass violin, it is hard to say with certainty which piece had been composed for which distinct instrument. For example, a Toccata a Violone Solo by Giuseppe Colombi (1635-1694) in his Libro 17 fits the basse de violon perfectly, not just because of the register that it comprises, but also because the composition is idiomatic to the instrument. As mentioned, this piece can be played as well on an 8’ violone six string G violone.

To give an example of a solo piece that descends to a Bb', I added a video in which I am playing Galli´s sonata no.10 in Bb Major from his Trattenimento musicale Sopra il violoncello. Although Galli specifies the violoncello in his title, this piece must be played with a bottom Bb' string. First of all, it uses that note more than once in the sonata. Lacking this bottom string, the player must transpose the Bb’ to a higher octave. Secondly, this Bb’ tuning suits perfectly the technique that is required to play the sonata. Playing this piece on an instrument tuned in C, the performer will have to jump constantly between the notes, making shifts uncomfortable.

The basse de violon, functions as a solo instrument and as the bass of ensembles

Il y a des manieres de le toucher qui en rendent le Son grave & triste, doux & tendre etc. C’est ce qui fait qu’il est d’un si grand usage sur tout dans les Musiques étrangeres, soit pour l’Eglise, soit pour la Chambre, le Théatre, &c.1

There are ways of playing it that render the sound serious and sad, soft and tender, etc. It is this manner that is used so much in foreign music, whether for the Church, for the Chamber, or for the Theater, etc.2

In his Dictionnaire, Brossard describes the violin as the perfect instrument to play in every situation. Did he have the whole violin family in mind when he wrote this?

In this chapter I will discuss the role of the basse de violon in France in different settings. Once more, the terminology presents us with a dilemma. Often there is a single word to describe one type of bass in a musical score. Composers and theorists of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries usually refer to the continuo instruments as a group and did not specify the particular instruments of that group. Most depictions of musicians playing on the street or in taverns for the common folk, or performing at court and playing for royalty, show ensembles rather than soloists. In 1592 Zacconi explains briefly why members of the violin family should play in an ensemble instead of alone: 'an instrument which produces one part only, wants to have some others to complete the ensemble'.3

-

The basse de violon in the streets

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the bass violin was played mainly in violin consort. The violin family, unlike the viol family, was not limited to performing at court. In the depictions and treatises of the time, we find references to violin consorts at every type of gathering. In 1591 Vincezo Galilei gives us a clear impression of the violin and the violinist:4

Violinists belonged to the common folk […] sonatori da balli are loved and favored by the common people.5

As the violins were so common to see and to hear, Praetorius didn´t bother describing them in detail.6 If the consort were playing in the street, it was very common for the player of the bass violin to fasten the instrument onto his body, as we saw in the previous chapter.

Most of the time the bass line which was played on the basse de violon was simple and didn´t require much effort, but there are also a few pieces in which it had its own virtuoso solos. For example, a basse de violon àcinque cords has a solo in Charpentier’s Sonate pour two flûtes allemandes, two dessus de violon, one basse de viole, one basse de violon à 5 cordes, one clavecin and one théorbe (1685).

-

The basse de violon in the church:

In France the violin family was not accepted in church as early as it was in other countries, such as Italy, even though the church played an important role in music education. Known cellists were taught in the maîtrises, the principal source of music teaching in the provinces of France. Most likely, cellists such as Barrière, were taught by basses de violons players who were retraining themselves and taking on new roles. Sadly, there is not much information preserved about the basse de violon players in the maîtrises.

However there is information that players of the basses de violons, in addition to their employment in the maîtrises, took part in the events outside of Paris. The basse de violon players also participated at times in church events and parts of the church service. A document from 1720 in the Sainte-Chapelle du Palais shows that the basse de violon had been employed:

A deposit to a “jouer de basse de violon” for having ”accompagné la musique dans les grandes festes depuis environ six mois”7

The religious musical scene in Paris was different. In the seventeenth century the bowed string instruments began to appear in religious life. These instruments formed part of the Chapelle. In 1702 there were already fifteen musicians, four dessus, one haute-contre, one taille, one quinte, three basses de violons, one theorbo, two traversos, a bassoon, and a cromorne. This small ensemble was mainly used for performing sacred cantatas and motets. For a big celebration, such as a royal wedding, royal births or funerals, other instrumentalists were added. There were even occasions during which the Vingt-quatre Violons played with the members of the Chapelle. The biggest number of musicians documented was when Lully conducted his Te Deum for the wedding of Carlos II of Spain and Marie-Louise d’Orléans in 1679, counting one hundred and twenty performers, both singers and instrumentalists.

-

The basse de violon in the orchestra

As John Spitzer and Neal Zaslaw write in their book, The Birth of the Orchestra, there were four leading bass instruments in the eighteenth century orchestras; the basse de violon was one of them.

the bass viol—a viola da gamba in the 8-foot register with six or more strings and a fretted fingerboard; a large 8-foot violin-family instrument with four to six strings and a long neck, that went by the names basse de violon, violone, Bassgeige, and others; the violoncello, a smaller 8-foot instrument—essentially the modern cello; a 16-foot viol-like instrument with three or four strings, called violone, contrebasse, contrabasso, or double bass.8

Regarding the bigger ensembles in France, the basse de violon had a place within the orchestra of the Vingt-quatre Violons du Roi and the Petit Violons. There were two different groups of strings, the petit choeur and the grand choeur, making possible a dynamic contrast.

King Louis XIII of France in the seventeenth century created this big ensemble which, according to John Spitzer and Neal Zaslaw, became the largest, best disciplined, and most renowned orchestra of the day.9 This orchestra played at various events, outdoors and indoors. At times the players of the basse de violon must have used a posture different from sitting down with the instrument placed between the knees.

-

Petit Violons

This ensemble, known as the Petit Violons, the Petit Bande and the Violons du Cabinet, was created around 1648 for King Louis XIV. As John Spitzer and Neal Zaslaw write, it is not known if the ensemble took such names because of its size or because of the young age of the child-king when the ensemble was created.10 The members of the ensemble, in contrast with the members of the Vingt-Quatre Violons du Roi, lived most of their music lives around the court. The ensemble was responsible for travelling with the king for his delight.11 The musicians resided in the palace, first in Saint-Germain-en-Laye until 1680, and later at Versailles.

The number of members varied much during its existence, having as many as twenty five musicians before being disbanded. At the beginning it was a band of only string instruments, but, in contrast to the Vingt-Quatre Violons du Roi, it was formed in a more Italian style. From 1692 until 1715 it had a constant number of upper voices: seven dessus, two haute contre, three taille and two quinte. The number of basses de violons was less stable: from 1692 until 1698 there were four, and from 1698 until 1715 there were five. This ensemble comprised also wind instruments. There was dessus de cromorne, bassons, dessus d´hautbois and hautboi.

Concerning the posture of the basse de violon players, most of the depictions of the time show the players sitting down. But still, in some cases, such as the Ballet masquerade that was celebrated at court with the instrumentalists being the first to enter the hall, I believe the basse de violon player would have fasten his instrument to his body.

-

The Vingt-quatre Violons du Roi

Apart from its role in religious events as previously discussed, the grande bande des Vingt-quatre Violons had further duties. As explained in État de la France, ou l’on voit tous les princes, ducs & pairs, marêchaux de France,12 the Grande Bande des Vingt-quatre Violons played when the king commanded, for whatever purpose, such as ballets, weddings and so on. On his return from his travels with the Petit Bande, the king would be received by the musical performance of the Vingt-quatre Violons.13 This ensemble rose to such importance that it became a source of pride and envy for the Bourbon court.

The musicians didn´t play only at court; sometimes the whole ensemble was hired to play outside the court and outside Paris, even if their conductor was not present. It seems that they were able to perform independently.

During most of the existence of this orchestra, there were six basses de violons. The number of basses differed in the period from 1692 until 1702 when there were seven basses de violons.14 After 1702 there were again only six. Even though there is a record of the musicians who played in the orchestra from 1676, it is not known if after 1702 they were playing basses de violons à quatre cordes, à cinque cordes or violoncelles, as many of musicians played multiple instruments. One of the prime examples of a 'multi-instrumentalist' is Théobaldo di Gatti, who first appears in 1676 in the État de la France as a viol player and later, in 1713 and 1719 as a basse de violon player.15

-

The basse de violon as part of a small ensemble

The basse de violon fit well within small ensembles. Even though it was part of the violin family, the viol remained the bass violin of choice for a long time. As previously mentioned, most players of the basse de violon would also have played the viola da gamba. Because of this, they were able to alternate instruments depending on the requirements of a piece of music or the preference for an instrumental timbre. As example of the viol used to accompany the violins, we see Brossard´s copies of Jacquet de La Guerre´s sonatas in which he asks specifically for the 'viola da gamba obligata con organo' to play the bass line.

Also in Jean-Fery Rebel´s sonatas there is an indication for the use of the bass viol. Rebel was very familiar with the sound produced by the basse de violon as he had been the leader of the Vingt-quatre Violons for some years. One can deduce that he chose to accompany his violin sonatas with a bass viol because he was interested in the contrasting sounds of the violin and the viola da gamba.

Considering the basse de violon in small ensembles, we see it accompany not just string instruments but also wind instruments. For example, Lully does not specify the instrumentation for some of his trios. He might have writen them for strings, winds or for both. In playing together with wind instruments in ensembles using flutes, it appears that the bass would have been played on a basse de violon or perhaps a viola da gamba. Lully´s trios LWV 35 for two trebles and a bass are a perfect illustration of how well a violin ensemble suits this piece.

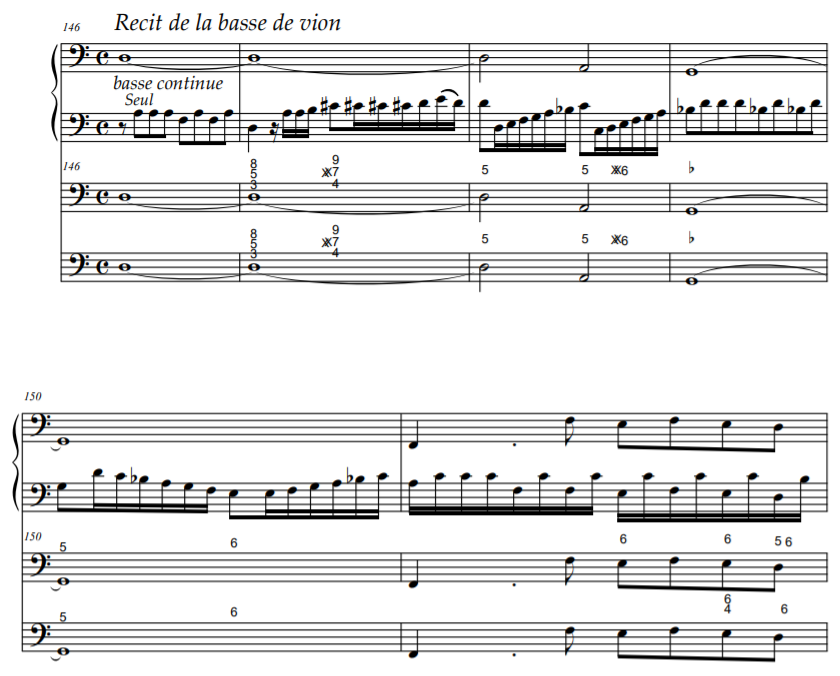

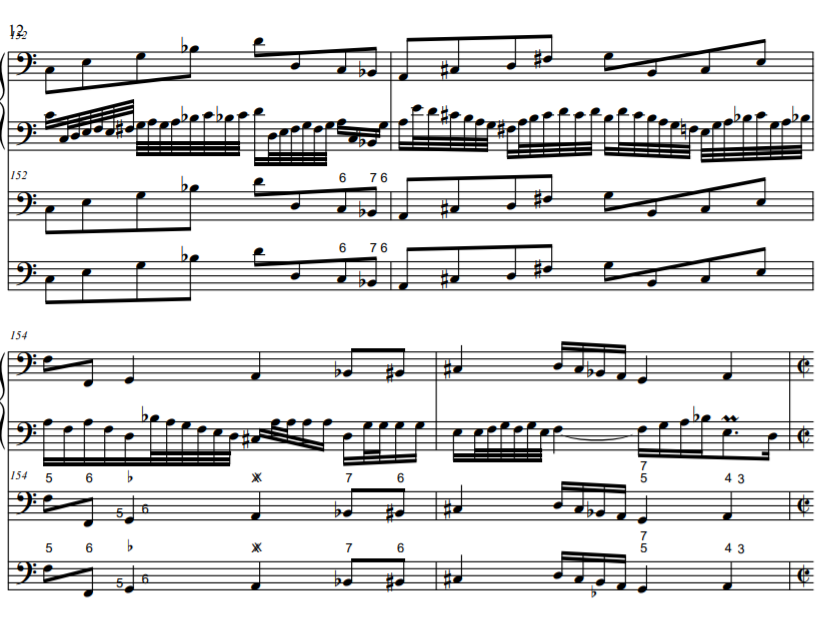

Figure 30 Extract from Marc-Antoine Charpentier´s Sonata, ed. by Alessandro Bares (Albese con Cassano: Musedita, 2010), 8.

Figure 26 Crispijn de Passe the Elder: Musical Company (1612). From: Academia sive speculum vitae scolasticae.

Figure 33 François Puget: Musiciens de Louis XIV (c 1687). Some scholars have identified Théobaldo di Gatti as the musician player who is standing on the left.

Rondeau from Lully´s trio LWV 35.

Violin 1: Elana Cooper

Violin 2: Victoria Klaunig

Basse de violon: Blanca L. Martin