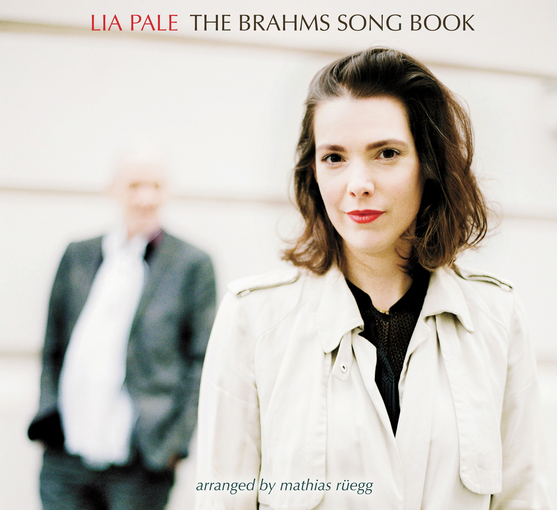

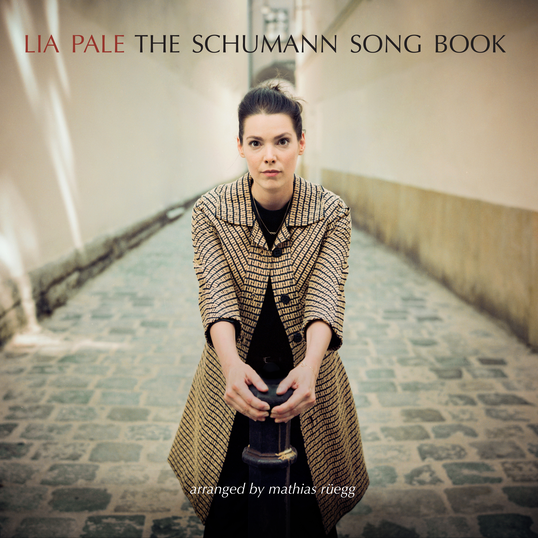

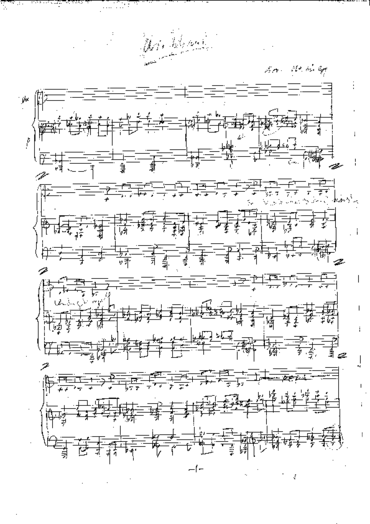

Der Leiermann from Winterreise op.89

performed by Julia Pallanch

in the arrangement by mathias rüegg

Widmung [Dedication]

You are my essence, you‘re my heart

You are my joy, my counterpart,

You are my world, in which I live in,

My heaven you, to which I give in,

You are my grave, in which

Forever I my sorrows gave!

You are my ease, you are my peace,

You are from heaven sent to me,

That you love me makes me feel worthy,

Your gaze has changed just how I see me,

You lift me up through loving me,

My good soul, my better me!

Find the whole cycle including pdfs, soundfiles and poems right here.

Find the whole cycle including pdfs, soundfiles and poems right here.

Find the whole cycle including pdfs, soundfiles and poems right here.

Gute Nacht [Good Night]

As stranger I arrived,

As stranger I shall leave,

I came and May was kind to me

With many flowers and bouquets.

I met a boy who spoke of love,

Our wedding day was planned.

But now the world seems overcast,

Deep snow lies on the land.

I cannot choose the time to leave

My journey it must be now,

And though I walk in the darkness

I find my way somehow.

A shadowdrawn by moonlight

Will walk by my side,

And on the white meadows

I seek the deer’s trails.

Why should I stay here longer,

until they drive me away,

Let stray dogs howl

Outside their master’s house.

Love wanders where it pleases,

God made it in his sight

It breaks the heart it seizes,

And so my love, good night.

I won’t disturb your dreaming,

And spoil a sleep so pure,

You will not hear me leaving,

I’ll softly close the door.

And on yourgate I’ll write good night

As I am passing through

So when you chance to see it,

You’ll know I thought of you.

Little Red Rose

Saw a boy a little rose,

Red rose on the heathside

Lovely, young in morning light

Had to run up closer.

Spellbound by her beauty,

Little, little rose so red,

Red rose on the heathside.

Said the boy: I'll pick you now,

Red rose on the heathside

Said the rose: I‘ll prick you back,

So that you won‘t forget me,

I shall not surrender.

Little, little rose so red,

Red rose on the heathside.

Yet the wild boy picked the rose

Red rose on the heathside

Red rose faught back with her thorns,

But it didn't help her,

Had to let it happen.

Little, little rose so red,

Red rose on the heathside.

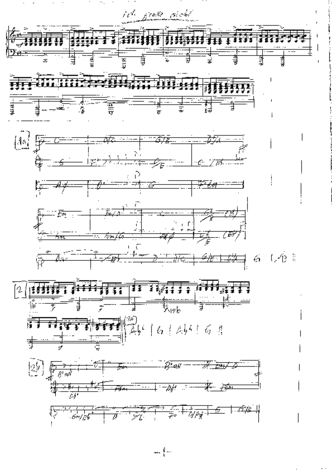

Ich grolle nicht [I don't complain]

I don‘t complain, though I may die of pain,

Love forever lost!I don‘t complain.

For you may shine like diamonds clear and bright,

I see your heart remains in darkest night,

I always knew.

I don‘t complain, though I may die of pain.

I saw you while I was dreaming,

I‘ve seen the night that through your heart is streaming,

I‘ve seen the pain that pierces through your heart,

I‘ve seen, my love, how sad you truly are.

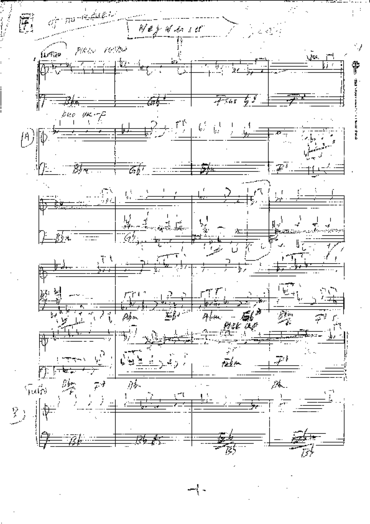

Wegweiser [Road of No Return]

Was vermeid' ich denn die Wege,

Wo die ander'n Wand'rer geh'n,

Suche mir versteckte Stege,

Durch verschneite Felsenhöh'n?

Habe ja doch nichts begangen,

Daß ich Menschen sollte scheu'n,

Welch ein törichtes Verlangen

Treibt mich in die Wüstenei'n?

Weiser stehen auf den Straßen,

Weisen auf die Städte zu.

Und ich wandre sonder Maßen

Ohne Ruh' und suche Ruh'.

Einen Weiser seh' ich stehen

Unverrückt vor meinem Blick;

Eine Straße muß ich gehen,

Die noch keiner ging zurück.

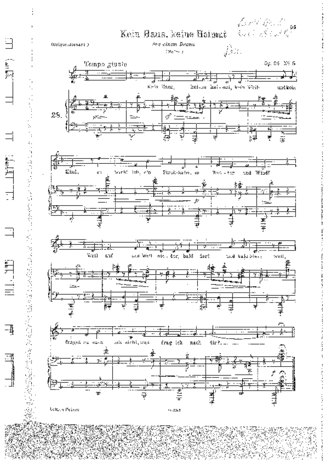

No House, No Home

No house, no home,

No wife, no kid,

I‘m tossed like a feather

Through weather and wind!

Once up, and then down,

Blown here and then there,

World, if you ignore me,

Well, why should I care?

My jacket's still whole

And my glass full of gin!

World, just go your way,

I won‘t ask where you‘ve been?

Wirtshaus [The Tavern]

Auf einen Totenacker

Hat mich mein Weg gebracht;

Allhier will ich einkehren,

Hab ich bei mir gedacht.

Ihr grünen Totenkränze

Könnt wohl die Zeichen sein,

Die müde Wand'rer laden

Ins kühle Wirtshaus ein.

Sind denn in diesem Hause

Die Kammern all' besetzt ?

Bin matt zum Niedersinken,

Bin tödlich schwer verletzt.

O unbarmherz'ge Schenke,

Doch weisest du mich ab ?

Nun weiter denn, nur weiter,

Mein treuer Wanderstab.

Ich hab im Traum geweinet [In my dreams I've been crying]

In my dreams I’ve been crying,

I dreamt you lay there in a grave,

Then I woke up, and my tears

Kept streaming down from my cheek.

In my dreams I’ve been crying,

I dreamt that you‘d walked out on me.

Then I woke up, and I cried

Still for a long time.

In my dreams I’ve been crying,

I dreamt that you still were with me.

Then I woke up, still I am crying

Leaving floods of tears.

Faith in Love

"Oh drown, deep down your grief,

My child, in the sea, in the deep blue sea!"

A stone may stay on the ocean's bed

My pain will show again.

"And your love, that you carry in your heart,

Tear it up, let it go, my child!"

Though a flower may die, once it is picked,

True love won't break like this.

"'And faith, and faith,

T'was only a word, let it go out with the wind."

Oh mom, though the rock erodes in the wind

Still my faith it shall endure.