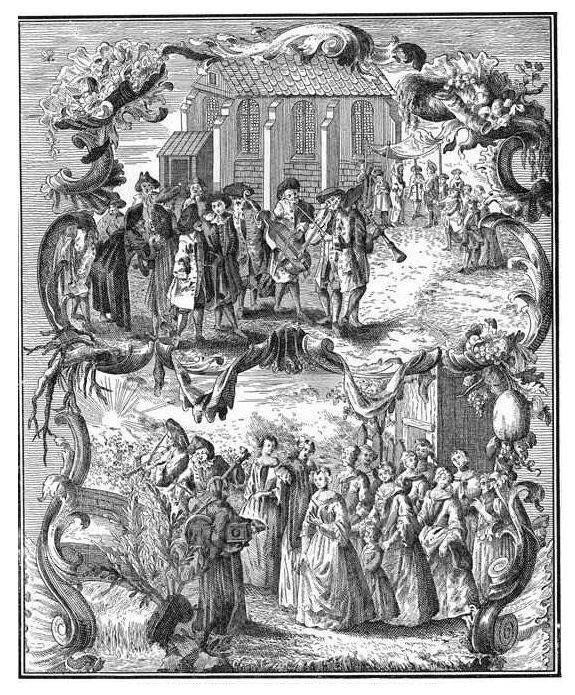

Figure 1 Title Page W.A. Mozart Musikalischer Spaß, Vienna: André 1797

Was the Double Bass the conventional bass instrument in the Divertimento Sextet, and if so, how would this influence today’s approach to divertimento performance practices?

Robert Franenberg, Double Bass

Royal Conservatoire, The Hague

Student number: 3342840

26 June 2023

Research Supervisor: Kathryn Cok

Circle Leader: Paul Craenen

Introduction

In 2000, I took part in a project performing all of W.A. Mozart’s (1756-1791) Salzburg divertimentos for strings and winds in the quaint town of Delft in the Netherlands. In attempting to keep true to authentic performance practices we played on period instruments with one player to a part and most significantly the bass line was to be performed solely on the double bass; thus, no cello and no cello/double bass doubling of the bass line.1 Some of my colleagues involved in this project found this to be quite a ‘radical’ idea, for in chamber music settings many musicians are accustomed to the cello as the bass instrument of choice, and depending on the repertoire, a double bass might double the line, but double bass alone…impossible! Indeed most recordings I have heard of these pieces have been performed by a chamber orchestra or as chamber music with the bass line performed by a cello and double bass.

Salzburg in the 18th century had a rich tradition of serenade music, which was performed for a variety of occasions to honour an individual, such as a person’s name day, a wedding, a graduation and other important events. Unique to Salzburg was the Finalmusik. The students of Logic and Natural Sciences at the Benedictine University would separately commission large-scale orchestral works, which were performed by a mixture of students, court musicians and amateur musicians from the community to celebrate the end of the academic year; thus the name Finalmusik.2 Mozart’s Haffner Serenade KV 250 was another large-scale orchestral serenade similar to the Finalmusik. In fact, the Mozarts even referred to this piece as a Finalmusik. Since these serenades were performed outdoors, it is believed that cellos did not take part in these performances; exclusively double bass and bassoon performing the bass line.

In addition to the large-scale serenades, Mozart also wrote a number of small-scale works such as the divertimentos. This was the repertoire that we performed during the project in Delft. The scoring of these pieces was varied: first KV 247, 287 and 334 for two violins, viola, two horns and bass, second KV 251 with the same instrumentation and the addition of an oboe, and finally KV 205 for violin, viola, two horns, bass (and bassoon). This is all wonderful music, but my two favourites were KV 247 and 287 known respectively as the1st and 2nd Lodronische Nachtmusik. Mozart wrote these divertimentos in 1776 and 1777 for the name day of Countess Maria Antonia Lodron, wife of Count Ernst Maria Lodron.

Scouring the Répertoire International des Sources Musicales (RISM) database for divertimentos with this same scoring as KV 247 and 287, I found pieces by Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) and Michael Haydn (1737-1806), Karl Ditters von Dittersdorf (1739-1799), Johann Baptist Vanhal (1739-1813), and Anton Zimmermann (1741-1781). After these discoveries, I began to wonder if this instrumentation could be a ‘standard ensemble’ like the string quartet and coined the term Divertimento Sextet for it. I was also curious if the double bass would have been the standard bass instrument in this ensemble. My research question is therefore: Was the double bass the conventional bass instrument in the mid 18th century Austrian/South German divertimento scored for two violins, viola, two horns and bass?

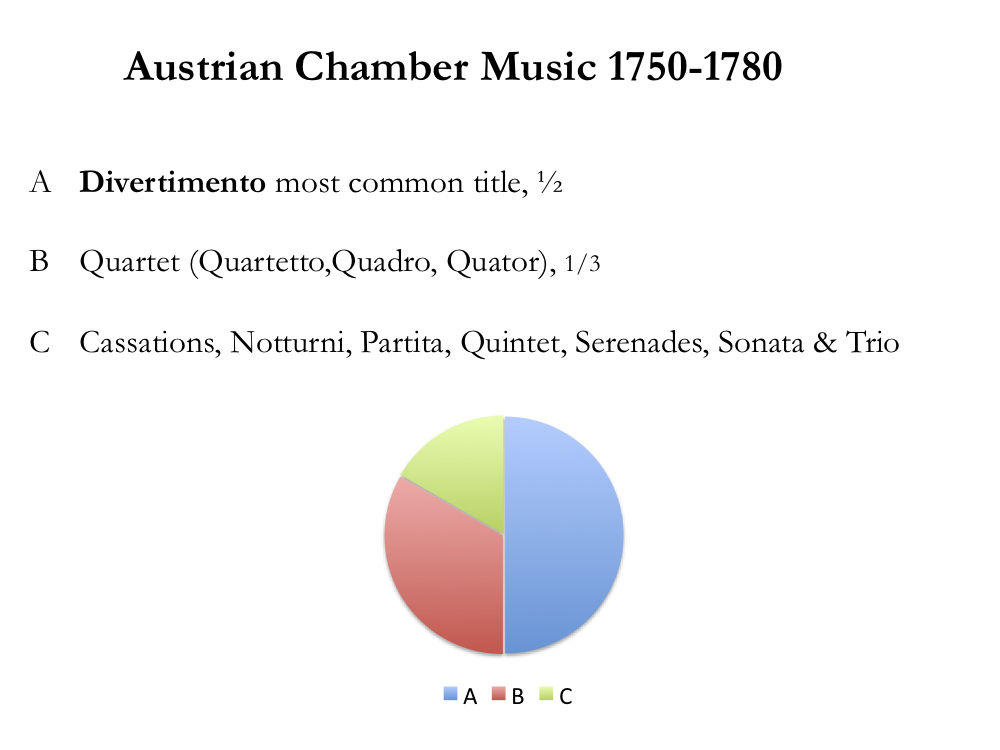

The first step in answering this question was to find out what a divertimento was in Austria in the period between 1750 and 1780. Most authors agree that the term divertimento refers to instrumental music played by one player per part. Divertimento was the most popular term for chamber music in late 18th century Austria and southern Germany. More than half of the manuscripts of Austrian chamber music written between 1750 and 1780 preserved in libraries throughout Europe bear the title divertimento.3

In a significant proportion of divertimento manuscripts, the term ‘basso’ is used to denote the bass line. However, the term ‘basso’ simply means ‘the bass line’ and does not indicate a specific instrument. During the 18th century in Austria, the double bass was referred to as violone or contrabasso. Thus, when these terms or other specific terms such as violoncello or fagotto (bassoon) are used in a manuscript, it becomes clear which instrument is supposed to play the bass line. Nevertheless, given that divertimentos were typically performed with one player per part, the use of the term ‘basso’ to designate the bass line poses a problem in determining the appropriate instrument to play the part.

Knowledge of the tuning of the double bass in this period, especially the lowest note of the instrument was of importance in examining divertimento manuscripts to observe if the bass part stays within the range of the instrument. The manuscripts tell the real story.

Much of this research was devoted to investigating title pages and bass parts of manuscripts to determine if the double bass might have been used in a particular piece.

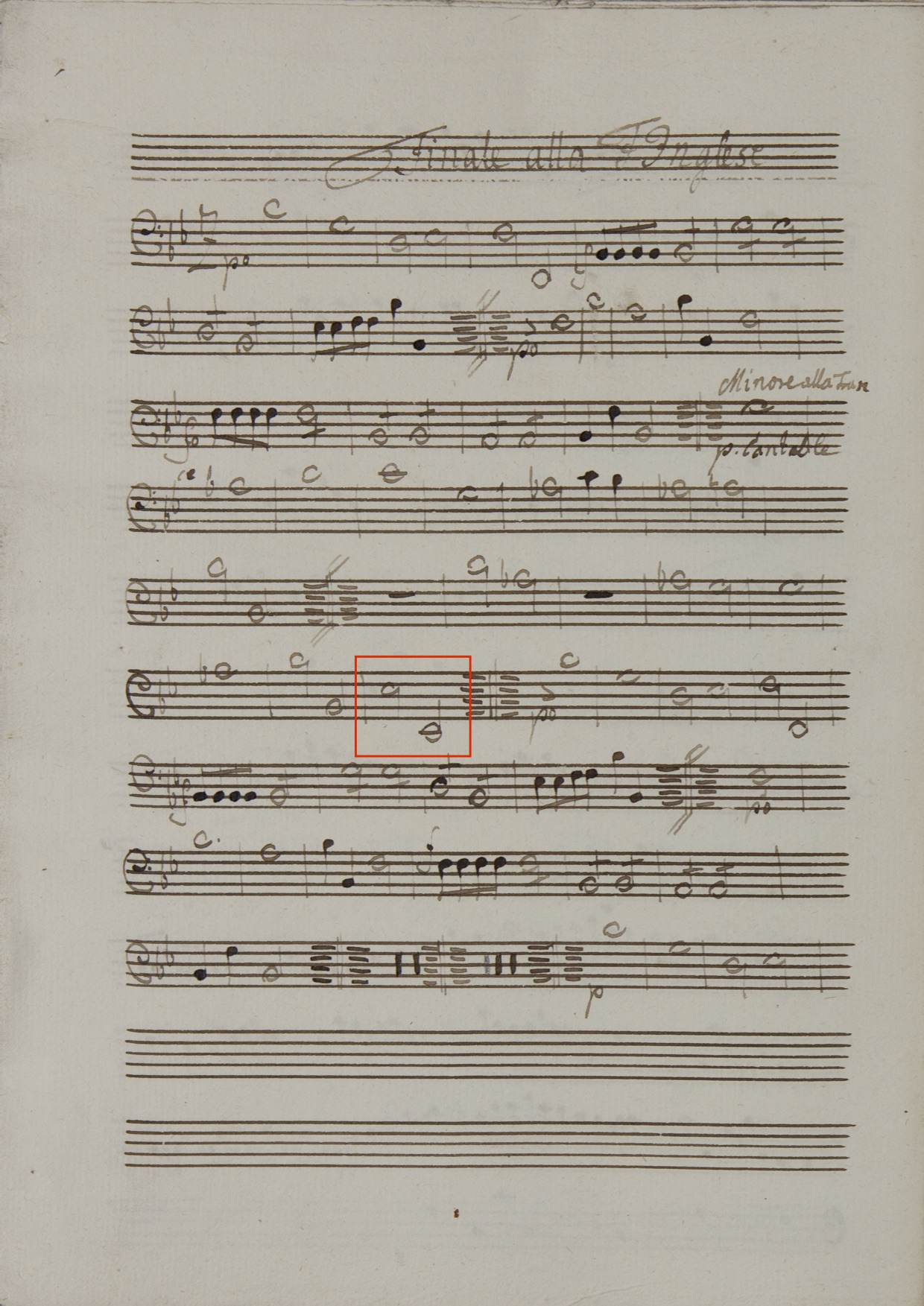

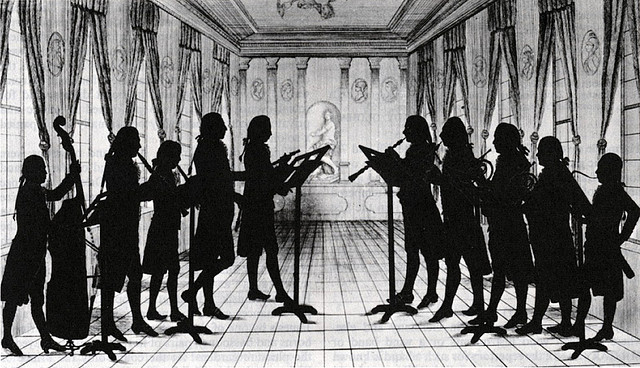

Aside from the title page of a print of Mozart's Ein Muskalischer Spaß KV 522 (Vienna: André, 1797), I could find no other iconography depicting a Divertimento Sextet. However, there are pictorial examples from the 18th century that show ensembles performing outdoors with the double bass serving as the only bowed bass instrument.

By looking at historical records of social events and occasions, I wanted to show that the double bass was the conventional bass instrument used in divertimentos for entertainment or background music. However, despite the wealth of detailed information contained in these accounts, specific details about the musical performance itself were often lacking. This lack of information ultimately prevented me from conclusively demonstrating the use of the double bass in these contexts.

Through this study I have gained an understanding of the 18th-century Austrian divertimento, the ambiguous term ‘basso’, and the tunings and nomenclature of the double bass of the period. By analyzing various primary sources in the form of manuscripts, I was also able to come to a conclusion regarding the possible use of the double bass as the standard bass instrument in the divertimento ensemble consisting of two violins, a viola, two horns and a bass.

Chapter 1

What is a divertimento?

The key to understanding Austrian chamber music in the period 1750-1780 is the term divertimento.4

According to Google Translate, the Italian word divertimento translates into English as fun, entertainment, enjoyment pleasure, and amusement.5 This could imply that divertimentos were music of a fun, light or entertaining nature. And indeed the most popular title for entertainment music in the period 1750-1780 was divertimento.6 The divertimento fulfilled a variety of functions indoor and outdoor during the 18th Century. It is generally accepted that the divertimento was primarily associated with the social life of the aristocracy, rather than that of any other class. However, towards the end of the 18th century, wealthy burghers had the resources to fund their own Kappellen and provide occasional musical entertainment for their social circle.7

As entertainment music, the divertimento can be classified as a subcategory of serenade music. Serenades were known since the Renaissance as a lover’s song to his beloved, which was played under her window on a starry evening. In the 17th century the aristocracy and upper classes adapted the honorific function and the outdoor setting of the lovers song to celebrate special occasions such as name days, birthdays, weddings and promotions.8 Other occasions for outdoor music were “garden parties, street serenades, marches, field music, carnivals, circus, tower music, farewell music and other entertainments; those for indoor music were court dinners, assemblies, convocations, coronations and inauguration music, as well as music for cafes, and opera, ballet, and pantomime. Any special day such as these would present an occasion for indoor or outdoor music depending on the season.”9

Even though it was most the popular title used for entertainment music in this period, divertimento cannot be defined with any accuracy, for as Hans Engel states, ‘the divertimento is a type of music for entertainment without any formal definition.’10 Despite this, many divertimentos were written as what we would call ‘serious’ or ‘learned’ music.

The first known use of the term divertimento as a title was by Carlo Grossi (1634-1688) in a set of vocal pieces, ‘Il Divertimento di Grandi musiche di camera o per services da Tavola all’uso delle Reggi Corti’, (Venice1681).’ “This title makes clear the closeness of the divertimento to banqueting music; a relationship maintained to some degree much of the 18th century.” The first use of the term in purely instrumental music was Giorgio Buoni’s (1647-1693) Divertimento per camera for two violins and continuo op.1 (Bologna 1693).11

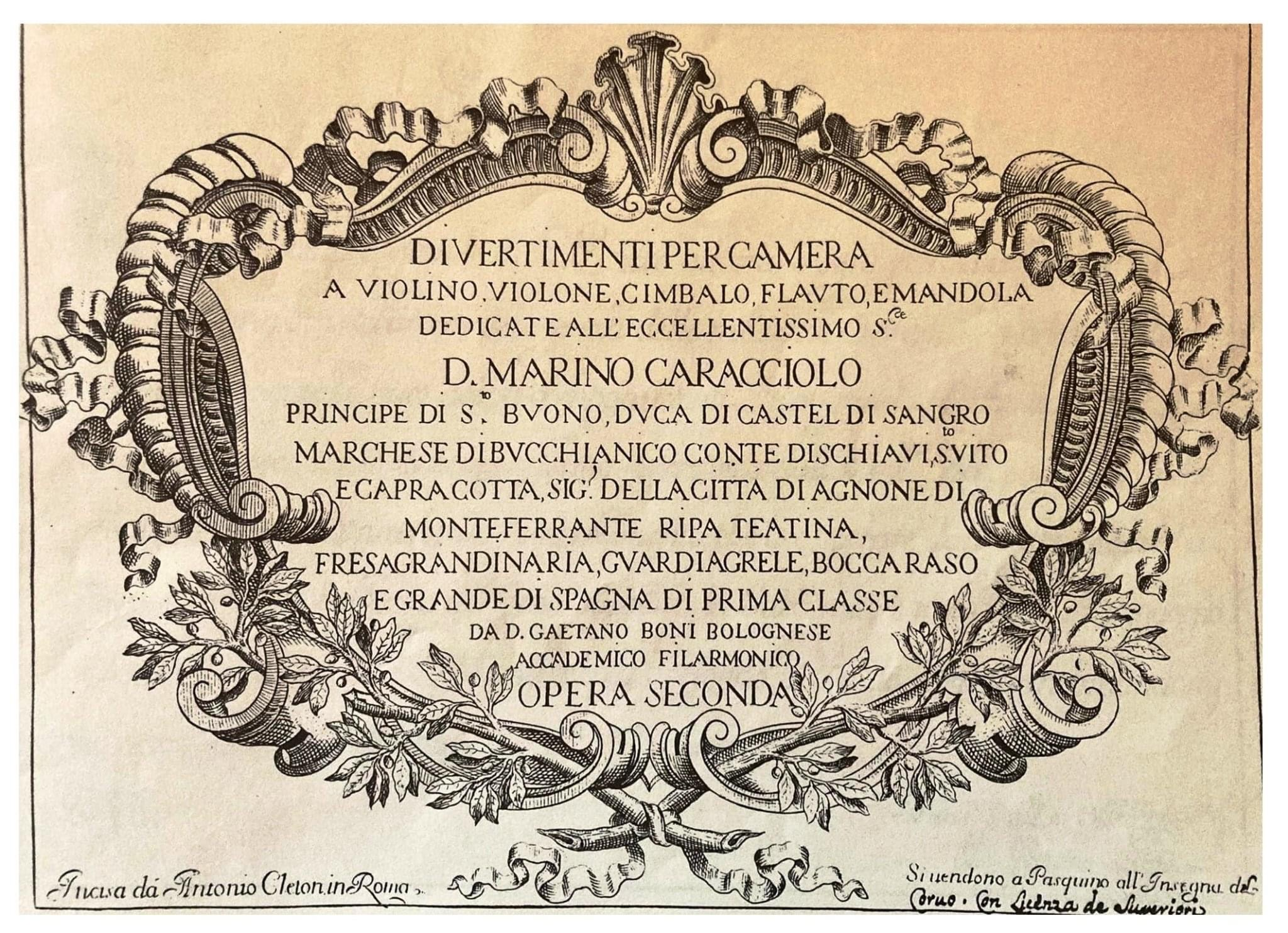

In the early 18th century Pietro Giuseppe Gaetano Boni (2nd half 17 century – 1750) composed his ‘12 Divertimenti per camera a violino, violone, cimbalo, flauto e mandola, op. 2’, which was published in 1720 by Antonio Cleton in Rome (Figure 2).12

Figure 2 Title page, 12 Divertimenti per camera, Pietro Giuseppe Gaetano Boni

Some of the earliest instrumental divertimentos were related to the French suite, such as Johann Fischer’s (1646-1716) Musicalisches Divertissement of 1701.13 Here Fischer uses the French form of the term. In 17th and 18th century French opera divertissements were played as interludes to the action, consisting of short pieces such as ballets, dances, and ‘entr’actes’ which merely served to entertain without being essential to the plot of action.14 According to Eve Rose Meyer in her dissertation, Florian Gassmann and the Viennese Divertimento, "Despite the fact that the divertimento was indebted to the French divertissement, and that it took its name from the Italian form of the word, the divertimento was purely German, with the center of composition in Austria." Guido Adler described the divertimento as "the best part of the Austrian musical soul."15 This study examines the divertimento in Austria in the 18th century, focusing on the period between 1750-1780, when it reached its artistic peak.

In the 1740’s and 1750’s divertimento, as a title, came into vogue in Vienna, popularized by Mathias Georg Monn (1717-1750), Johann Christoph Mann (1726-1782), and others. There has been some confusion regarding the identities of the two composers, Monn and Mann who are believed to be brothers. Mathias Georg was given the name Johann Georg at birth and his family name was Mann, not Monn. It is assumed that Johann Georg changed his name to Mathias Georg Monn to avoid being mistaken for his younger brother. However, in the region of Lower Austria where the brothers were born, the vowel "a" is commonly pronounced as "o." Therefore, it's possible that the elder brother's name was spelled as Monn due to the regional pronunciation, rather than a deliberate change in spelling.16

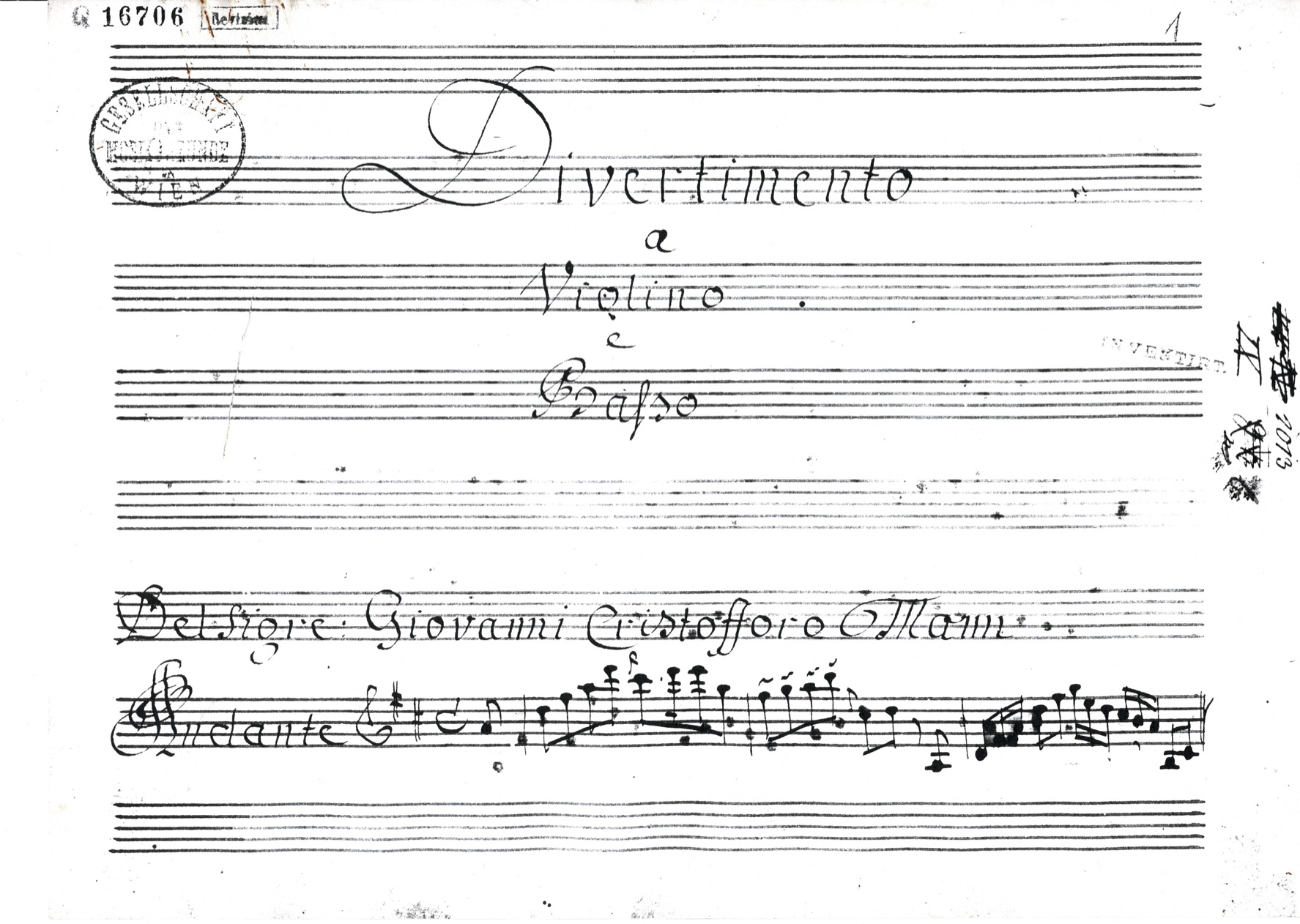

Before the 1750’s the majority of ensemble works, like those of Monn and Mann, were trio-sonatas for two melody instruments and bass, called variously Partita, Sonata, Trio, Divertimento, and even Sinfonia.17 A divertimento manuscript by Matthias Georg Mann, originally located in the Prussian State Library, is titled: ‘Divertimento a 2 alto-Viole con Basso / del Sigr. G.M. Monn’. Housed in the library of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna are 11 divertimento manuscripts by J. C. Mann. A set of seven entitled ‘Divertimento à 3’, another set of three entitled ‘Divertimento a Violino Primo, Violino Secondo, e Basso’ and a duet, entitled ‘Divertimento a Violino e Basso’ (Figure 3).18

Figure 3 Title page Divertimento a Violino e Basso, J. C. Mann

The divertimento is thought to have evolved from a combination of the French suite, Italian sonata da camera and elements of solo and grosso concertos, Italian sinfonia, opera, dances and folk tunes. The compositions of Monn and Mann are considered the missing link between the baroque suite and the divertimento.19

The years 1750-1780 are considered a transitional period in music. In the 1750s, basso continuo was still a crucial element in the sonata and suite. In the 1760s, however, it was used more freely, and in the 1780s it was completely replaced by bass instruments, such as the violoncello or bassoon.20 The evolution of music form the baroque period to the galant witnessed the emancipation of the bass instrument from the continuo line. It is clear from sources that by 1750, in secular Austrian chamber music the use of continuo was starting to be abandoned. This can be seen by the titles used in these sources, which almost always avoid the words Cembalo and Continuo.21 It remains uncertain whether the bass lines were written as continuo parts in Leopold Gassmann's (1729-1774) works during this transitional period. Although there is no mention of continuo in any of the titles, and no figures are included, this lack of information does not provide conclusive evidence that continuo was not employed.22

The divertimento made a significant contribution to the development of richer musical textures. Following the decline in the use of the harpsichord, composers began to write for ensembles in a way that did not rely on the continuo to fill in the gaps. This led to the harmonies being distributed more evenly throughout the inner voices, with the second violin and viola gradually gaining more prominence. Music was frequently performed in public spaces, such as streets or palace courts, as entertainment and background music. Due to the limited sound projection of the harpsichord, it was not used in these settings and composers started to adopt the aforementioned approach in their writing.

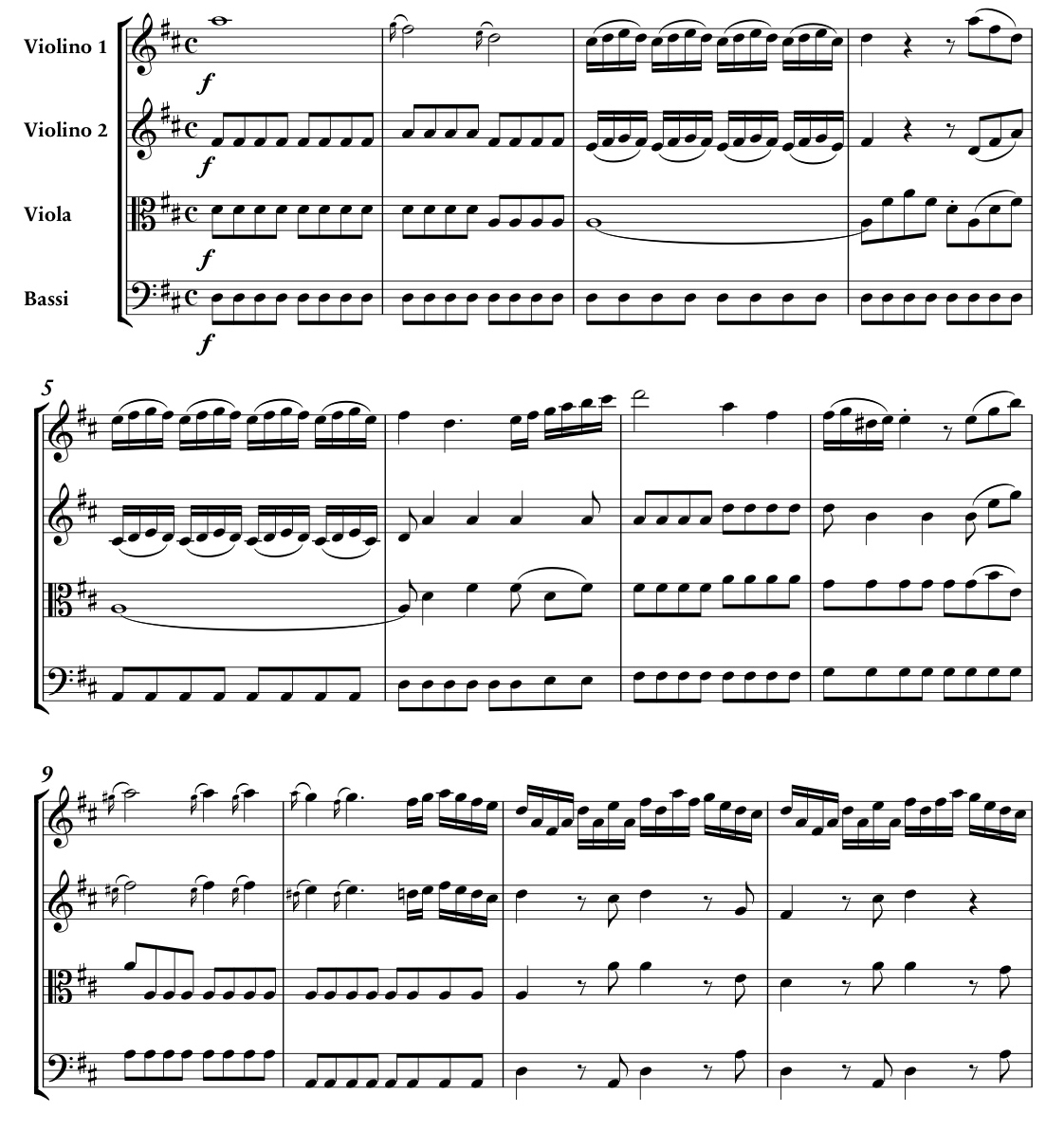

The emergence of the galant style marked a shift in musical composition, characterized by a move away from counterpoint and towards a more homophonic writing style. This style featured a prominent upper melodic line, supported by inner voices and a bass line. Harmony in this style was often conveyed through the inner voices, while the role of the bass line transitioned from the melodically active voice in the late Baroque period to one that served primarily as a harmonic foundation. This bass line was often comprised of repeated notes, the so-called Trommelbass, which served to enliven the overall rhythmic progression of the piece.23 W. A. Mozart’s Divertimento KV 136, written in Salzburg in 1772, is an example of the galant style. It is worth noting, however, that according to Alfred Einstein, Mozart himself did not give the title Divertimento of this piece (Figure 4).24

Figure 4 W.A. Mozart Divertimento in D KV 136

Among the aesthetic principles of the galant style, music, above all, was meant to please. According to Leopold Mozart, "It should exhibit a certain ease of manner and never bring sweat to the brow; it must charm by a light touch rather than astound either by bravura and pyrotechnics or by rhythmic, harmonic and contrapuntal complexities, which are said to be ‘unnatural’". Leopold Mozart urged his son to write in an easy style.25

The musical output of the generation between J.S. Bach and Mozart was characterized by its lightness, brevity, and simplicity, as opposed to the seriousness, complexity, and grandeur of the previous generation's music. This shift in style can be seen in the contrast between Andreas Werckmeister's 17th century definition of music as “a gift of God, to be used only in His honor,” and Charles Burney's 18th century statement that music is an “innocent luxury, unnecessary, indeed, to our existence, but a great improvement and gratification of the sense of hearing.”26

In the period from 1750-1780 the title Divertimento was the most commonly used for Austrian chamber music, appearing in local sources for nearly half of the works. The second most common title was Quartet, which accounted for approximately one-third of the works. Other frequently used titles included Cassation, Notturni, Partita, Quintet, Serenades, Sonata and Trio (Table 1).27

Table 1

However, despite its prevalence, there are very few descriptions of the divertimento by contemporary writers. J.C. Koch provides a definition in his Musikalische Lexikon of 1802 as summarized by Webster, “divertimento is a genre (‘Gattung’) of instrumental music, comprising compositions for two, three, four, or more parts, performed by soloists; its several movements are neither ‘polyphonic’, nor as long and complicated as those in sonata-type works, nor distinguished by any particular expressive content (‘Charakter’) They are mere ‘tone-pictures’, intended more for the hearer's delectation than his edification.”28 Koch refers to a number of the characteristics of the galant style. In this context, a divertimento is defined as light music that can be performed by any number of players, with one player per part.

Haydn's numerous keyboard trios from the 1750's and early 1760's are titled both Partita and Divertimento but his mature trios from the 1780's and 1790's are titled Sonata.29 By the 1760's and I770's Divertimento was the principal designation for all non-orchestral instrumental music, including ‘serious’ sonatas and quartets. 30 Thus, even though the term divertimento could imply light music, not all were occasional or entertainment music, which is best exemplified by Haydn’s early string quartets.

Haydn titled his string quartets through op. 20 (1772) as Divertimento. His early quartets were written in the slender galant style best described as, mainly homophonic, almost no counterpoint, a dominant top line supported by the other voices, and balanced phrasing. In his op. 20 quartets Haydn employs techniques of ‘serious’ music such as the use of counterpoint and a more equal role of all the parts. One writer states of op. 20, “The quartets are considered a milestone in the history of composition; in them, Haydn develops compositional techniques that were to define the medium for the next 200 years. The six string quartets of Opus 20 are as important in the history of music as Beethoven's Third Symphony would be 33 years later.”31 And this is what Haydn titled Divertimento!

One notable example of the use of the term divertimento can be found in a letter by Leopold Mozart dated 15 October 1777. In this letter he advises his son on how to locate music copyists upon arriving in a new location, “You should try to find a copyist and…you should do this wherever you stay for any length of time…Then…have in readiness copies of symphonies and divertimenti to present to a Prince or some other patron (Liebhaber).”32

What was the nature and purpose of the divertimentos referred to by Leopold? Were they intended to serve primarily as a form of entertainment, or did they possess a more serious musical intent, such as that typically associated with string quartets? It is possible that the term ‘divertimento’ is being employed in this context as a synonym for ‘chamber music’.

As mentioned, divertimento is by far the most common title in Austrian chamber music between 1750 and 1780, appearing in local sources for nearly half the works.33 It transmitted the most variety of scorings and styles.34 The diversity of scoring in Joseph Haydn's divertimentos is exemplified in Category II of, Joseph Haydn, Thematisch-bibliographisches Werkverzeichnis (Joseph Haydn, thematic-bibliographic catalogue of works) compiled by Anthony van Hoboken (1887-1983) between 1934-1978. Category II, distinct from the String Quartet Category III, is dedicated to compositions for four or more parts and demonstrates Haydn's experimentation with various instrumentations, as evidenced by the 45 distinct instrumentations present among the 47 entries in this category. Haydn's biographer, Karl Geiringer, notes that a defining feature of these compositions is the composer's “inexhaustible interest in sound effects (colors).” This catalogue provides a valuable resource for understanding Haydn's approach to instrumentation and his use of various timbres in his compositions.35

Besides the diversity in divertimento scorings, there is also no limit to the cyclic patterns of multi-movement divertimentos. The most common types are:

-

The three movement ‘Italian overture’ F-S-F

-

Various threes movements with minuets; F-S-M, S-M-F, S-F-M, F-M-F (Haydn’s Baryton Divertimentos are three movement works).

-

The four movement F-S-M-F, F-M-S-F, F-S-M-F

-

The symmetrical F-M-S-M-F

References have been made to the pre-classical cycle formations F-M-S-F and the five movement F-M-S-M-F cycle as being relatively widespread models that correlate with the term divertimento in the solo string repertoire á Tre and á Quattro, particularly in certain regions and periods. However, it is important to recognize that the term divertimento does not inherently imply adherence to any specific structural cycle. For example, Mozart's Lodronische Nachtmusik comprises of six movements (F-S-M-S-M-F) and some examples of divertimentos feature up to eight movements, thus it would be fallacious to make a universal correlation between the term "divertimento" and specific structural cycles.36

Interchangeably

“In Haydn’s time it was difficult to separate the various types of instrumental music, since one and the same piece was often called by different names. The terms divertimento, serenade, cassation, partita, and nocturne were used almost or entirely arbitrarily in the chamber music of the second half of the 18th century for no other reason that one or the other happened to be expedient either for the composer, copyist, or publisher.”37 “Modern scholarship has tended to define musical genres primarily in terms of internal elements such as structure, instrumentation, style and individual work titles. In contrast, 18th-century authors also defined musical genres in terms of a work's social function and performance setting. The term ‘serenade’ was used for a wide range of compositions and did not necessarily imply a specific musical structure or instrumentation. However, the titles given to serenade music often reflected the specific occasion or context in which they were performed.”38 Some examples are:

-

Serenata, an honorary function

-

Finalmusik, specific occasion

-

Cassation, performance venue, outdoors

-

Notturno, time of performance

-

Divertimento, solo instruments

-

Partita, solo instruments, often a designation for a wind ensemble

The term cassation (cassatio) is of special interest in the context of Mozart's compositions. He used it to refer to large-scale serenades, such as the Finalmusik and also divertimentos. In fact, Mozart specifically referred to three of his early serenades as cassations: KV 63, 99, and 100. The origins of these names do not come from the autographs. Instead, they are mentioned in a letter Mozart wrote to his sister on August 4, 1770, where he shared the themes (incipits) of his ‘Cassationem’.39 Mozart also uses the term cassation when referring to the two Lodronische Nachmusik, Divertimentos KV 247 and 287. On 2 October 1777 W. A. Mozart writes to his father from Munich:

“For three days at Count Salem's house I played through various pieces from memory, then the two Cassations for the Countess, and the Finalmusik music with the Rondeau, all from memory.”40

In Munich, a few days after playing for Count Salem, Mozart gave a small private academy in his flat, at which he, as a violinist, played a divertimento for his guests. He writes on 6 October 1777:

“For good measure, I played the last Cassation of mine in B. Everyone looked at me with great interest, I played as if I were the greatest violinist in all of Europe.”41

After moving to Vienna in 1781 on 4 July, 1781 he soon wrote to his father, asking him to send him some of pieces:

“I absolutely need the 3 Cassations - if I can have the ex f and B in the meantime - you could have the ex D copied for me and when you have the opportunity, send it on later.”42

The origins of the term cassation are not entirely clear, but it is believed to have originated from the expression ‘gassatim gehen,’ meaning, ‘to prowl the streets.’ One of its earliest uses was by Michael Praetorius in his Syntagna Musicum (1619) meaning ‘to go serenading’.43 The word may also have roots in the Italian ‘cassare,’ meaning, ‘to say farewell’ and the Latin ‘cassationem,’ meaning ‘the act of cancellation,’ suggesting that it may have originally referred to music played at the end of an evening's entertainment. 44 However, over time, the term ‘cassation’ was replaced by ‘divertimento.’ This is evident in the Entwurf-Katalog of Joseph Haydn, where Haydn’s copyist Joseph Elssler originally titled the early quartets as ‘Cassation’ until around 1770, after which the term ‘Divertimento’ was used. Haydn even went so far as to cross out ‘Cassatio’ and replace it with ‘Divertimento’ in later catalogs. According to H.C. Robbins-Landon, Haydn may have felt that there was no difference between ‘Cassatio’ and ‘Divertimento’ and wanted to standardize the term for the genre.45

The first reference to the use of the title Divertimento in the works of W.A. Mozart is by his father, Leopold, in the entry of the catalogue of his son’s early works in 1768, “6 Divertimenti a 4. fur verschiedene Instrumenten: als violin, clarino, corno, flautotrav: fagotto, Trombone viola, violoncello etc.” Unfortunately, these pieces have been lost.46 Mozart’s KV 113 for two clarinets, two horns, two violins, viola and bass is the first existing work of his using the title Divertimento. Composed in Milan in 1771 during Mozart’s second trip to Italy, the first page of the autograph score bears Leopold’s title ‘Concerto o`Sia Divertimento à 8 del Sgr: Cavaliere Amadeo Wolfgango Mozart in milano’ and dated ‘Novemb: 1771’.47 It is interesting that Leopold uses the two terms in the title. The term ‘Concerto’ in the title might refer to the strong contrast between the strings and winds in the piece. Since the piece was written in Italy he might have wanted to give the piece a contemporary Italian title. Furthermore the use of the term ‘divertimento’ would imply chamber music of a light texture.

Divertimentos were written with a wide range of styles, scorings and movement cycles. One even finds a great variety in the titles used on divertimento manuscripts. Given all these factors of variance, writers have grappled with trying to define what a divertimento actually is.

Heinrich Philipp Bossler (1744-1812) wrote in his Elementarbuch der Tonkunst (l782) that a divertimento is “a generic name, applicable to a number of forms, but commonly applied to the cyclic sonata for one or more instruments.” 48

Daniel Gottlob Türk (1750-1813) stated in 1789 that divertimenti were instrumental, keyboard, or instrumental and keyboard pieces, which were less serious than sonatas or symphonies.49

The British musicologist Donald Tovey (1875-1940) in trying to explain the difference between the serenade and the divertimento stated, “if the combination of instruments was solo rather than orchestral, the composition would be called a divertimento.”50

H. C. Robbins-Landon (1926-2009) characterizes the ‘typical divertimento’ as a series of miniature movements containing two minuets to be performed by a loose grouping of instruments with one instrument to a part.51

In his scholarly analysis, James Webster offers a clear explanation of the concept of the divertimento in 18th century Austria. He maintains it was not a specific genre, nor was it limited to a particular style or instrumentation. Rather, it was basically a term used to describe a piece to be played by one player per part, such that an early Haydn string quartet titled Divertimento à quatro would simply correspond to our modern terminology as Composition for four instruments.52

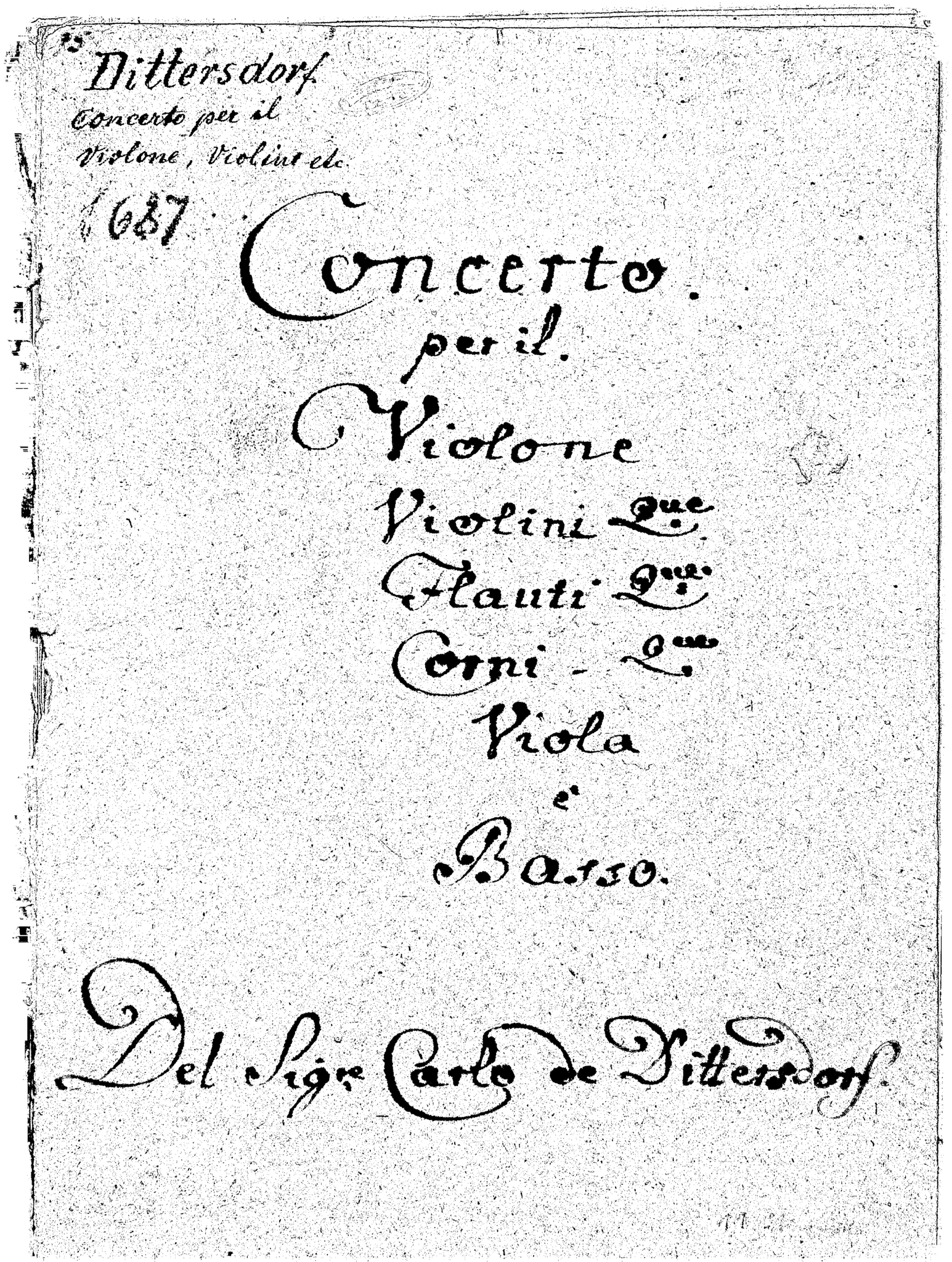

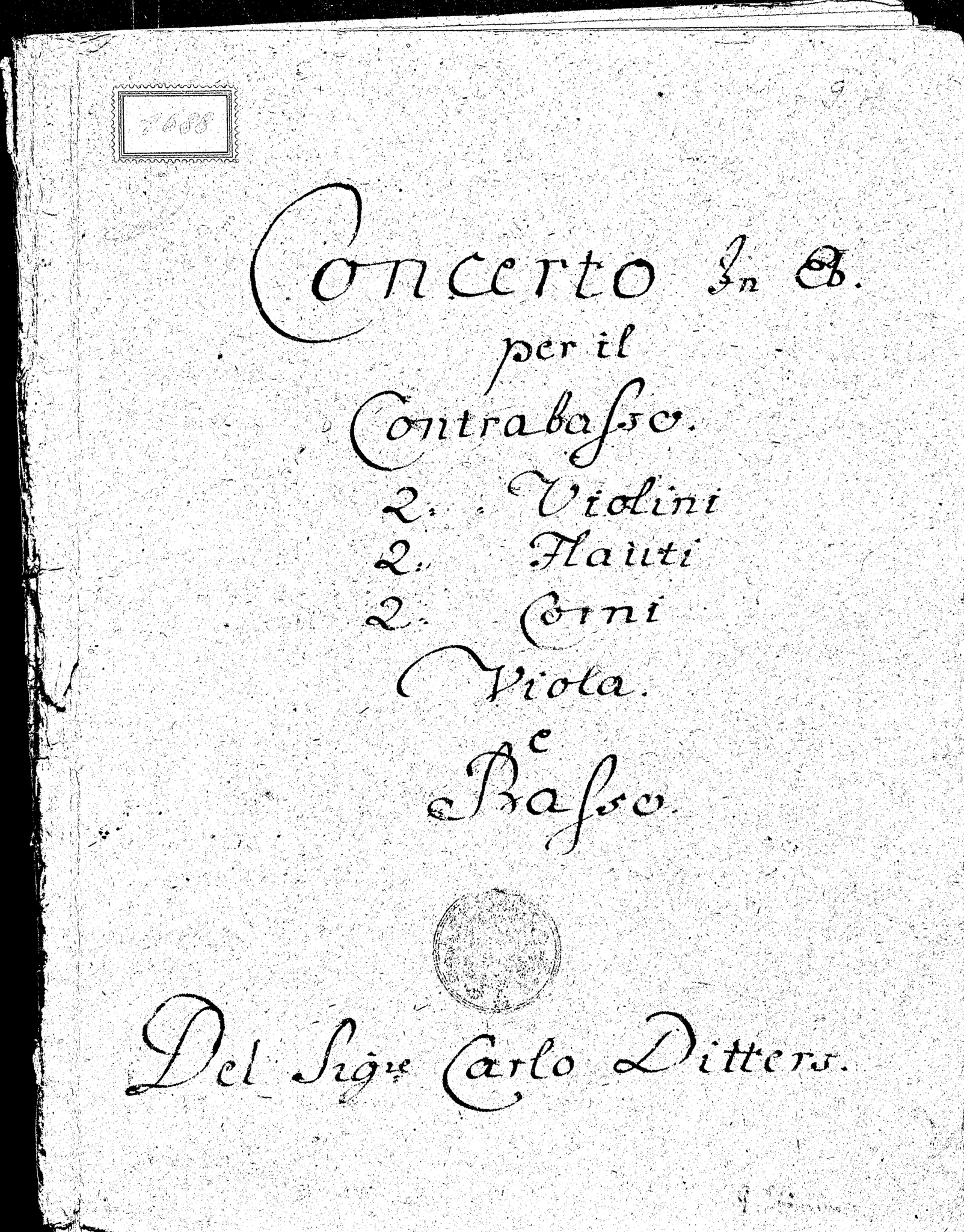

Figure 5 Title pages of Dittersdorf’s two Double Bass concertos

Dittersdorf wrote these concertos for the double bassist Friedrich Pischelberger (1741-1813) in 1767 when both were employed at the court of Bishop Adam Pattatich in Großwardein (now Oradea, Romania). The concertos that Dittersdorf wrote for Pischelberger are known as the ‘Pischelberger Konzerte’ and are considered some of the most important works for the double bass from the classical period. On the title page of one of the concertos the double bass is referred to as Violone, and on the other as Contrabasso.

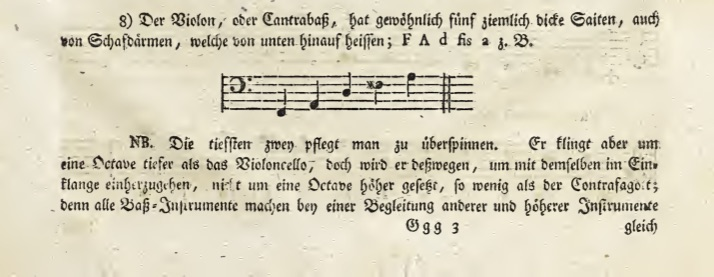

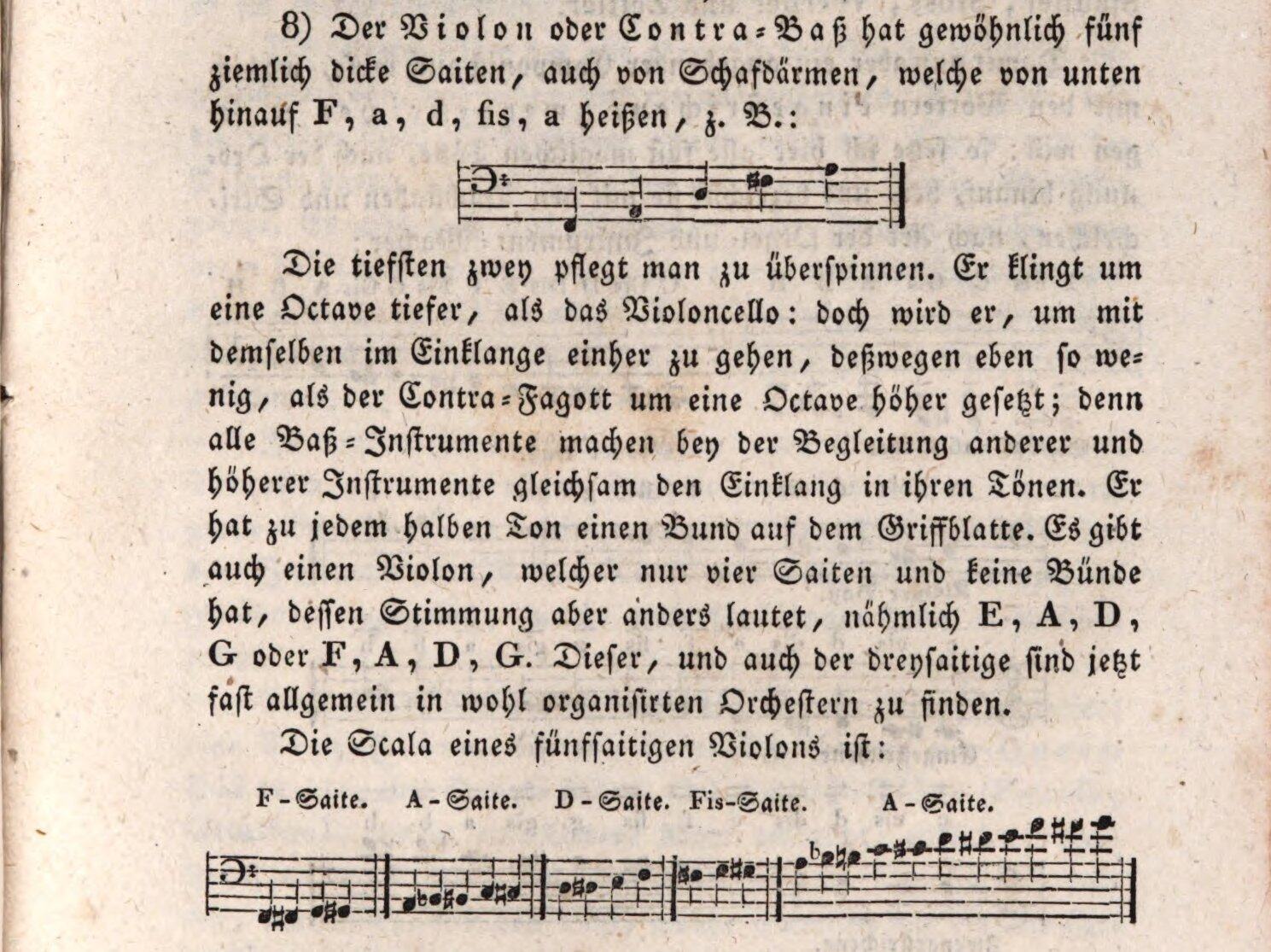

Throughout its history, the double bass has varied in construction, size, stringing and tuning. This was certainly also the case in the 18th century, as even the number of strings on the instrument varied from three to six; hence the many different tunings. Dr. C. Nicolai in his 1816 article, Das Spiel auf dem Contrabass, mentions twelve different double bass tunings. However, he mentions that the Violon is usually strung with four strings, but there are different ways to tune it. The most common was the reverse violin tuning, i.e. E-A-D-G.53Pischelberger played a 5-string instrument tuned to what we today call the ‘Viennese tuning’, F-A-d-f#-a. Nicolai also mentions this tuning in his article. Dittersdorf’s concertos were written specifically for this tuning. In fact, Pischelberger would have tuned his instrument a semitone higher, such that the solo part is written in D major and the orchestra accompaniment in E-flat major.54 An 18th century reference to this (Viennese) tuning can be found in the treatise Gründliche Anweisung Zur Composition, by Johann Albrechtsberger, published in 1790 (Figure 6).

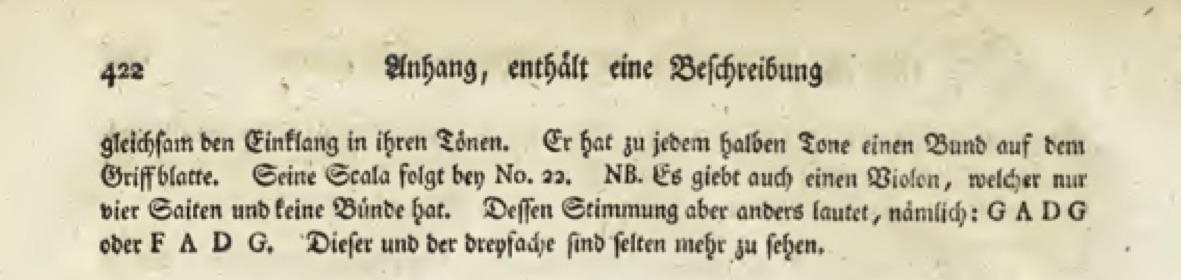

Albrechtsberger refers to the double bass as Violon or Contrabaß and states that the five strings are made of sheep gut, the lowest two of which are wound (with metal wire). Similar to the viola da gamba, a fret is placed at every half step on the neck of the instrument. He also mentions that there are four-stringed double basses (Violon), that have no frets and are tuned either G-A-D-G or F-A-D-G.

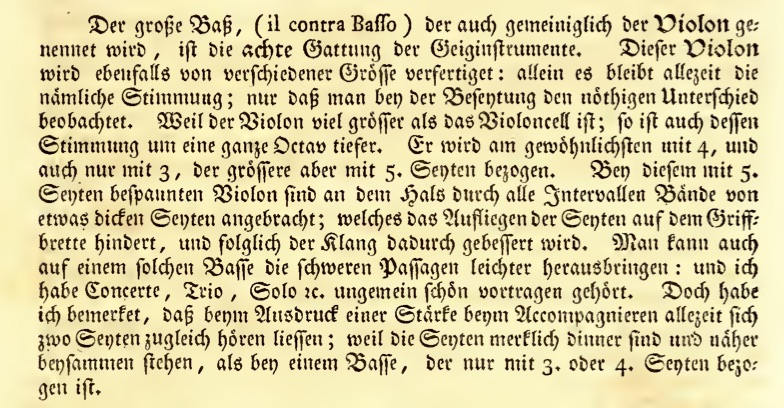

In an 1826 edition of his treatise entitled, Sämmtliche Schriften über Generalbaß, the tuning for the four-string double bass is listed as E-A-D-G or F-A-D-G (Figure 7).

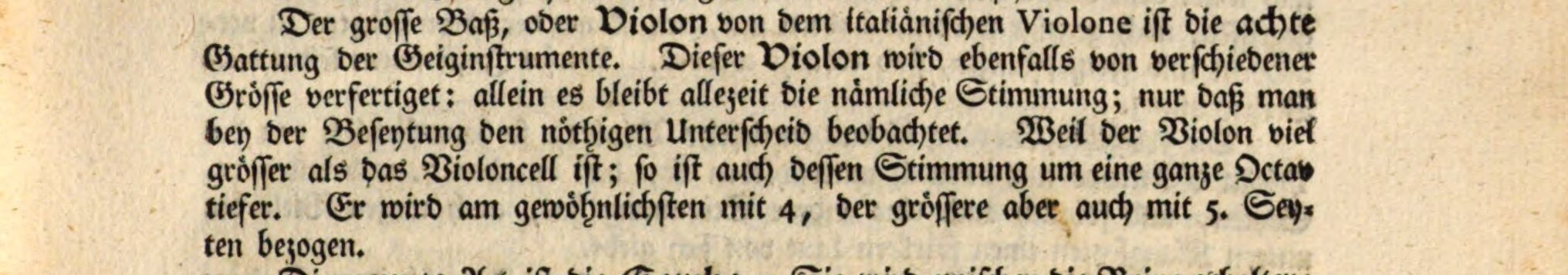

The great bass or Violon, from Italian ‘Violone’ is the eighth type of stringed instrument. This Violon is also made in different sizes; nevertheless, all have the same tuning, the only differences being in the stringing. Because the Violon is much larger than the violoncello, it is tuned a full octave lower. It is most commonly strung with four strings, the largest, however, with five.55

In the 1770 edition he elaborates further on the 5-string instrument (Figure 9).56

Figure 9 Description of the double bass in the 1770 edition of Leopold Mozart’s treatise

Unfortunately, Leopold does not give any tunings of the instrument; nevertheless he does mention that the double bass (Violon) is most commonly strung with four strings. Carl Bär concludes that the double bass used in Salzburg during Mozart’s lifetime was the four-stringed instrument in the tuning E-A-D-G, but admits that occasionally basses with a different number of strings and tuning were also played.57

The standard tuning of the double bass in the 20th century was E-A-D-G, but as late as the mid-19th century, some bassists preferred the low F as the lowest note of the instrument. The bassist Johann Hindle (1792-1862) gives an explanation for his preferred tuning in his method book:58

The open strings are tuned to F', A, D, G. Many will not understand why I tune the last string to F, since the low string is normally tuned to E. It is undeniable that the low E has a good effect in adagio and piano passages. However, the instrument must also be suitable for it. Rare is a double bass that has a pure, strong sound in the low register. Rare is a string that is suitable for low E tuning, usually they are very viscous and have an unintelligible tone, which is why it is also rare for a double bass player who has the ear to tune them purely, and so the low, untuned string often spoils more than it helps. Since the low E is very rare, but the low F' is always and frequently encountered, I tend to use the F tuning because it gives the string more tension and produces a more sonorous tone that can be tuned more purely for any ear. The notes F, F#, G, G# or A-flat are also much better in the hand for the transition to the open A-string, because you do not have to leave the first position. Any double bass player will easily understand this advantage and find it good.

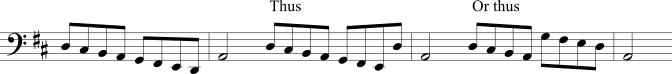

According to these references, the lowest note of the double bass in 18th century Austria was typically E1 or F1. This is an important consideration when studying divertimento manuscripts, as any notes below this range may not have been playable on the double bass. If a part includes notes that fall below the typical range of the double bass, it may be necessary to consider the possibility that a different instrument was intended. On the other hand, in 18th century orchestral music such as symphonies, operas, and orchestral serenades, the range limitations of the double bass were not an issue as they might have been in chamber music. Since the baroque era, it was common practice for double bassists to transpose notes or passages up an octave to compensate for the instrument's limited lower range. This method is illustrated in Figure 10.

Chapter 3

The Term Basso

One of the challenges in determining whether the double bass was the instrument of choice for performing the bass line in the Divertimento Sextet was the use of the term basso. The term basso simply means ‘the bass line.’ This is similar to the terms continuo and fundamento, which were used for the bass line in the baroque period. The term basso does not stand for a specific instrument or even for how many instruments should play the bass line. Unfortunately, this term has been misinterpreted in the past as referring to the double bass, for as mentioned in the previous chapter, the terms for the double bass in 18th century Austria were violone or contrabasso.

If one examines the scores of Mozart's works, it is generally the case that the bass line is designated by the terms basso or bassi. Based on the practice that was common during the baroque and classical periods, it was assumed that the violoncello and double bass lines in Mozart's works would have been performed in octaves. This interpretation would be correct for symphonies, concertos, and operas in 18th century Austria. However, it would be incorrect to assume that the use of the term basso in these works, implying that both instruments should play together, would also apply to solo divertimentos and string quartets. It is important to carefully consider the context and score of a specific piece in order to accurately interpret the use of the term basso in Mozart's works.59

In his symphonies up to the 1780s, Haydn almost always used the term Basso and rarely Bassi. This can be seen in the autographs of the symphonies Hob. I: 28, 31, 35, 40, 49, 55, 56, 85, and 89. Should he want to specify a particular instrument for example, Haydn inserts a separate staff as in the score of his symphony Le Midi, which he titles Violoncello obbligato and another staff Basso Continuo.60

Mozart's Symphony in C KV 551, ‘Jupiter’, shows the composer's attention to detail in terms of instrumentation, especially in the bass line. The bass line is titled Bassi and is intended for the violoncello and double bass. There are separate staves in the score for bassoon 1 and 2. In measure 3, Mozart indicates through the use of the term violoncello that only the cellos are to play the bass line. Later, in measure 5, the instruction tutti indicates that all bass instruments should play the bass line.

This situation occurs again in bars 7 and 9.These specific notations illustrate Mozart's meticulous approach to shaping the sound of the symphony and show the importance he attached to the roles of the individual instruments (Figure 11).

Figure 14 Title page of a Sinfonia by Josef Mysliveček

If the term basso simply means ‘the bass line’ in orchestral works, then the same should be applied to chamber music. James Webster states: “The overwhelming majority of manuscripts transmitting Viennese and Austrian Chamber music from 1750 to 1780 use Basso alone to designate the bass line.”61 In all authentic sources of Joseph Haydn’s string quartets through op. 20 (1772) the term Basso is used to indicate the bass line. Interestingly the authentic manuscript of Haydn’s op. 33 quartets (1781) bears the term Violoncello, but the Atari print still reads Basso.62

The use of the term basso in divertimento and its subgroups (cassation, notturno, serenata) can cause confusion regarding the intended instrument for the bass line, as the term can refer to either the double bass or cello. This can be seen in numerous divertimento manuscripts, where the term basso is used to designate the bass line on the title page and bass part, making it difficult to determine which instrument should play the part. However, in certain cases, the basso designation on the title page is accompanied by a specific instrument designation in the bass part, such as in Dittersdorf's Serenata in F, where the bass part is labeled ‘Violone’ indicating that the intended instrument is a double bass (Figure 15). Taking this piece as an example, it is evident that an examination divertimento of manuscripts would be necessary to establish if indeed the double bass would be the intended instrument in a Divertimento Sextet.

Chapter 4

Double Bass as Basso Instrument in Salzburg

In 1960, Carl Bär, published the article Zum Begriff des ‘Basso’ in Mozarts Serenaden, which shed light on the concept of the basso in W.A. Mozart's Salzburg Serenades. As mentioned earlier, the term basso in 18th century Austrian symphonies, concertos, and operas referred to the cello, double bass, and bassoon, all of which played the bass line. This ground-breaking research offers valuable insights into the musical practices of the time and the role of the instruments in classical compositions. On the basis of sources, Bär demonstrates that the bass line in Mozart's large-scale serenades, such as Finalmusik and divertimentos (played by one player per part), were performed with the exclusion of the violoncello. This resulted in a string section consisting of two violins, viola and double bass. This quartet, with its unique makeup, would then be recognized as a distinct group alongside the traditional string quartet and the orchestral string group. Bär invented the name "Serenade Quartet" for this string group.63

The general term serenade covers a wide range of forms that range from the Serenade itself to the Cassation, Notturno, Ständchen, Nachtmusik Divertimento, all which can be considered as entertainment music in the best sense of the word. Common to all of these is that they were commissioned works and were used as occasional music (Gebrauchsmusik). The music would have been composed for a specific purpose such as paying homage to the Salzburg court, the university, and noble and bourgeois families. Furthermore, with few exceptions, they were intended to be played outdoors. Given the outdoor performance setting, the double bass would typically be the sole string instrument used to play the bass line due to its ability to project its sound and be clearly audible in an open space. This characteristic of the double bass makes it a suitable choice for outdoor performances, where the presence of other instruments or background noise may diminish the clarity of the bass line played on a smaller string instrument.64 Jan Josef Horemans’ painting ‘Park Landscape with a Musical Party’ (1718) depicts a double bass as sole bass instrument playing outdoors (Figure 16).

Figure 16 Jan Josef Horemans, ‘Park Landscape with a Musical Party’

As a tradition of the Salzburg serenade, an ensemble would typically march to and from the performance venue. These serenades usually took place in the evening in front of the house of the person being honored and were attended by a large audience (‘die Halbe Statt’). The ensemble played the serenade in the open air, adding to the festive and celebratory atmosphere of the occasion. A distinctive feature of the Salzburg serenades is the semi-independent character of the march movement. In South German serenade manuscript parts, the head of the movement sequence begins with a march, but Salzburg march movements appear as separate scores or parts. For example, the march to K. 247, the 1st Londronische Nachtmusik, is a separate piece, KV 248. The most likely reason for this is that the marches were played by memory as processional and recessional music.65 Leopold Mozart makes reference to this in a letter to his son from 11 June 1778 where he complains that due to his bad memory he could not play the march, but just had to walk along within the procession.66 Since the parts of the marches were separate from the serenade/divertimento parts, they could be reused with other pieces in a similar key. At the performance site music stands would have been set up and after sunset the musicians played by torchlight. After the performance the same march would be played as the recessional music.

When considering music to be performed outdoors, there were factors that would have made it inconvenient to use a cello in the ensemble. Marching would have been possible with a cello as well as a double bass, provided the latter was of modest size and the music was not too technically difficult. Contemporary illustrations show small basses used for the serenades, which were suitable for both walking and standing. There are references to a traditional Salzburger Kleinbass, which was lighter and more manageable.67

Figures 17 and 18 depict double basses of smaller proportions being played outdoors.

In his treatise, Leopold Mozart notes that the double bass “is commonly strung with four strings, …the largest however with five.” The five-stringed double bass he refers to is the same instrument Albrechtsberger describes in his treatise, an example of the Viennese school of bass building of the 18th century. I have seen a number of these instruments and find that none of them is exceptionally large. The old cellos had a button in the middle of the back that could be attached to the player's skirt, otherwise they could be hung on a strap, which would also have been possible with a small double bass.68 Marching with bass instruments existed before the 18th century, as the following examples show (Figures 19-22).

After arriving at the performance venue, the ensemble played standing up. In the 18th century it was common for music to be performed standing up, not only outdoors but also in church and in the chamber, in the latter two cases the cellist played sitting down. Should a cellist play standing up, the instrument could be suspended by a strap, placed on a box or chair, or even equipped with a spike. The length of the spike would then have to be between 30 and 60 cm, depending on the height of the player, to bring the fingerboard to a comfortable playing height. In such cases, however, the instrument lacks stability: on the one hand, it wobbles on the spike, which is too long; on the other hand, the body of the instrument, which is slender in contrast to that of the double bass, offers insufficient inertial resistance to the impacts of the fingering and bowing hand acting on the longitudinal axis. A serenade performance with even partially seated players would have been completely inconceivable. Apart from the mobility factor (immediate marching to and from) that such an ensemble would have required, it would also have been unthinkable for social reasons that a court musician, i.e. a lowly servant, would have sat down in front of Archbishop Colloredo standing at the window, or indeed any other noble patron. 69

Acoustics

Concerning the notion of a cellist sitting in front of the Archbishop, Wolf-Dieter Seifert writes, “It would be a strange form of arrogance, if not stupidity, for a patron to deny a musician who performs for him the necessary tools for their music, in short, to deny a cellist a stool on which to sit during his performance.”70 Even if this is not a decisive argument in favor of the double bass over the cello, it is worth considering the acoustic properties of the instruments when performing outdoors. Those who have attended music performances outdoors may have noticed that low tones tend to be more audible at a distance than high ones, as seen in amplified rock music with the prominent sound of the electric bass and drums. In such situations, the double bass may be a more suitable choice due to its larger body and deeper tones, which resonate better outdoors compared to the cello.

In Mozart's Salzburg serenades for strings and winds, such as KV 247 and 287, the bass line is designated by the term Basso, which is not specific to any particular instrument. However, based on Bär's analysis, it is likely that these pieces were intended to be played on a double bass. Stanley Sadie also concurs with this interpretation, noting that the term Basso in these works typically refers to the double bass rather than the cello, and that the static nature of the bass part supports this conclusion.71

Additionally, Sadie points to two string quintets for two violins, two violas and bass by Michael Haydn, in which the lowest part is also named "Basso." In this case, he argues that the intended sound should be an octave lower than written pitch, and that a violone (double bass) would be required to achieve this effect.72

Mozart does make a clear reference to the use of a double bass in a serenade-like piece in his Serenata Notturna KV 239, which was composed in Salzburg in 1776. As with many of Mozart's compositions, it is not known for what occasion it was commissioned. Since it was written in January, it would therefore not have been performed outdoors. Serenata Notturna is a three-movement work resembling a concerto grosso, scored for a solo quartet and a small string ensemble with timpani. According to the autograph, the soloist quartet consists of, ‘2 Violini Prinzipale, Viola Prinzipale, and Violone’ (= double bass).73 The accompaniment group includes 2 violins, viola, violoncello, and timpani. The outdoor, street character of this piece may explain why Mozart scored the solo group for the Serenade Quartet. In addition to their duties at court and in the church, during Carnival, Salzburg musicians also performed in the archiepiscopal theatre and the ballroom. Given the comical elements of the Serenata Notturna, it is possible that it was intended for an event associated with this festive period.

The above mentioned solo quartet instrumentation of the Serenade Quartet can be expanded to include other instruments. For example, a pair of horns can be added, as in KV 247, 287 and 334, and a wind instrument such as an oboe can be added, as in KV 251.

‘Registral gap’ or hiatus

The use of the double bass in the Divertimento Sextet presents a challenge; as the instrument sounds an octave lower than written. This results in a missing 8-foot range in the ensemble, creating a ‘registral’ gap or hiatus between the viola and bass parts. This ‘hole’ in the sound spectrum could potentially be disturbing to the listener. However, the inclusion of two horns in the ensemble, often playing notes in the cello range, helps to partially bridge this gap. In addition, the double bass parts in these pieces are usually notated between c and c', a relatively high tessitura which, in combination with the relatively low viola parts, can help to reduce the perceived gap.74 Furthermore, the music in these pieces is primarily homophonic, with the double bass parts providing mainly harmonic and rhythmic support, in contrast to obbligato cello in the chamber music of this period, which exhibits notes in the high ranges, melodic passages, difficult figuration, and participation in thematische arbeit.75

Divertimentos, such as W.A. Mozart's KV 247 and 287, and Joseph Haydn's Hob.II: 21 and 22, scored for the Divertimento Sextet, feature adagio movements in which the horns are silent. This results in a lack of "filler" wherein the absence of the horn section is more noticeable. These adagios possess a chamber-music-like character, essentially functioning as solo movements for the first violin. The inner voices provide accompaniment, thereby making the absence of the 8-foot layer less noticeable. Furthermore, the sonorous bass sound of the double bass acts as a counterbalance to the solo violin, balancing the overall timbre of the ensemble.

It is important to remember that the musical pieces in question were created primarily for entertainment purposes and were usually performed outdoors rather than in concert halls where the discerning audience was more attentive. Being outdoors, the listeners may have been distracted by their surroundings and not fully focused on the music or the performers.76

Chapter 5

References to Divertimento Performances

During Mozart's lifetime, symphonies were not often critically discussed in contemporary writings. When they were mentioned, they were usually described with slight adjectives such as ‘excellent’, ‘brilliant’, ‘new’, ‘grand’, ‘festive,’ or ‘noble’. There are no known writings from Mozart's time that offer a detailed analysis or critical examination of his symphonies. In fact, it was not until 1818 that such an analysis was made, in Jerome Joseph de Momigny's study of Symphony KV 550.77 Given that symphonies were not widely analyzed during the 18th century, it is not surprising that little was written about the performances of occasional music like divertimentos and serenade music.

There are references in the correspondences within the Mozart family, though, as to the use of the double bass as the bass instrument in what Bär calls the Serenade Quartet. In a letter to his son, who at the time was in Paris, Leopold writes on the 13 of June 1778 about a performance of the 2nd Lodronische Nachtmusik (KV 287) during a Czernin Academy (Liebhaberakademie) in the Lodron Palace in Salzburg. Count Johann Rudolph Czernin (1757-1845) was an aspiring violinist. In 1778 he founded an orchestra, which played on Sunday afternoons at the Lodron family residence. The bass part in Mozart's Divertimento KV 287 reaches down to Eb1, lower than the typical range of the double bass in 18th century Salzburg. While the double bass was commonly associated with outdoor performances, it is worth noting that this performance took place in an indoor space. Therefore, the use of a double bass in such a setting cannot be ruled out.

But then H: Kolb played your cassation with the most astonishing sound. Everyone listened with the greatest silence, and after each piece, Count Wolfegg, Grand Zeyl, Grand Spaur and everyone else shouted “bravo il maestro e bravo il Sgr. Kolb!” The Countess Lodron, the Countess Lizow p: all were attentive and amused and the Countess only knew from the variations that you often had to play that this was her music, she ran to me full of joy and told me so - then I played the second violin, the viola was played by the Kolb student, the bass was played by Cassel, and the two major players, who had often played with Kolb, were the French horns.78

Thomas Cassel had been a double bass player on the court musicians' list since 1778, but he was also a violinist and flautist. It was normal at this time for musicians to play other instruments in addition to their main instrument. Cassel's main instrument must have been the flute, because the Mozart family friend Johann Baptist Joseph Joachim Ferdinand von Schiedenhofen (1747-1823) mentions in his diary a performance of a Mozart flute concerto with Cassel as soloist. That he played the double bass at these amateur concerts is evident from a performance a week earlier, as Leopold Mozart also reports:

2 Durnergesellen played the horn, violon geige, Cassl and the graf Wolfegg, also at times the Ranftl. violoncell, the new young canons, graf Zeil and graf Spaur, the HofRath Mölk, Andretter Sigerl and Ranftl.79

The 2nd Lodronische Nachtmusik was first performed in June 1777 as Schiedenhofen notes:

13. June 1777. In the afternoon I was with Moll at the Mozarts', where he was rehearsing the Nachtmusik which he intends to perform at the Countess Lodron's. "He also performed a repeat of the Serenade at the house of his doctor friend Dr. Silvester Barisani in front of invited guests: 16 June 1777 " Then H. v. Luidl, the two housewives and I went to the Barisannis to hear the music that young Mozart will play for Countess Ernst v. Lodron in the Octave; it was very beautiful. There were a lot of people at Barisani's.80

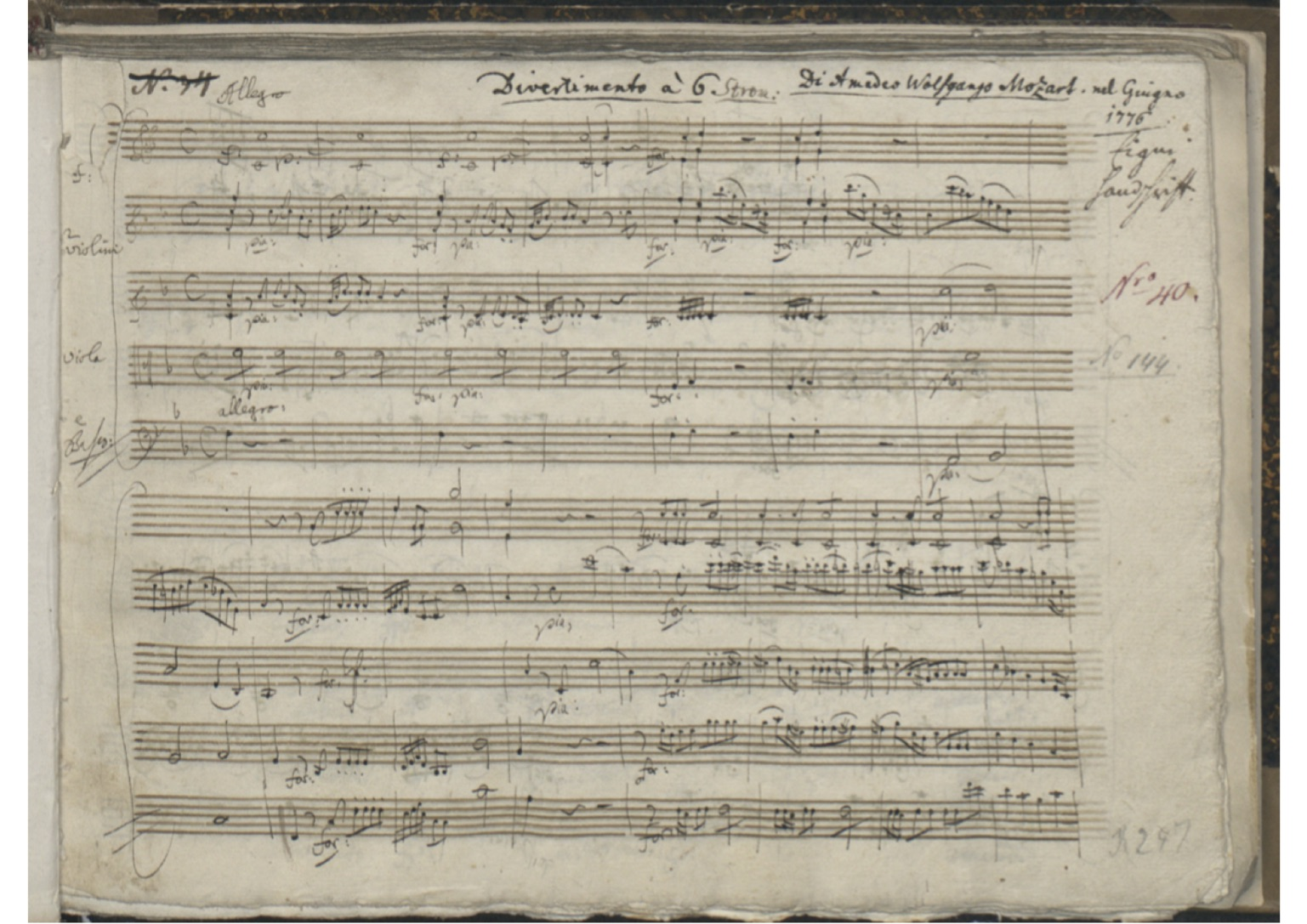

The first performance of the 1st Londronisch Nachtmusik (KV 247) is recorded in Schiedenhofen's diary on 18 June 1776. He writes: “After dinner to the music Mozart composed for Countess Ernst Lodron.” The autograph bears the title Divertimento à 6, written in Leopold Mozart's hand. The abbreviation ‘Strom:’ for the instruments is added in a different pen, indicating that the piece was to be performed for one voice per instrument (Figure 24).

Although there are very few references to actual divertimento performances, there are several references in sources that mention events in which social or entertainment music (Gesellschaftsmusik) was performed. However, while these sources often provide quite detailed descriptions of the event itself, little information about the music played is mentioned. One such example comes from Kremsmünster Abbey, which houses one of the most important music libraries in Europe. The monastery had a vibrant musical culture, featuring performances of operas, singspiels, and church music, as well as occasional music (Gebrauchsmusik). Neal Zaslaw suggests that in the Benedictine monasteries of Bavaria and Austria symphonies were employed as Tafelmusik.81 In any case, the following account reveals nothing of the repertoire played.

At Easter 1791, “an old opera was repeated”, and on 3 May, when the new provincial governor August Count Auersperg made his inaugural visit from Linz, a short opera, probably “Robert and Kalliste”, was given in the evening at 6 o'clock. The ceremonial reception with kettledrums and trumpets was omitted because the President arrived on horseback before the appointed time (while his family, accompanied by Count Salburg, did not arrive until around noon), but there was table music (Tafelmusik) at noon and in the evening.82

On 1 September 1773, the Austrian Empress Maria Theresa visited Prince Nicholas Esterházy, who gave her a royal reception at his palace in Eszterháza. The prince, who wanted to leave a lasting impression on the empress, had carefully planned and staged the event to demonstrate the opulence and influence of his house. According to a report on the empress's visit, a ceremonial luncheon took place on 2 September, combined with a parade of guests offering their compliments to the empress.

Her Imperial Majesty had dinner publicly in the drawing room upstairs. The table was set for 35 people and the way the meals were served was gorgeous. The decoration along the table, made with delicate taste, visualized three structural parts of the building, each curiously wrought; the barrier around it was topped with round relieves with different weapons from the prince’s collection. The fruits along with a few bonbons were put on the table with special care, with a lot of glassware made of crystal among them. During the dinner the prince’s several musicians, who all were excellent at playing their instrument, had the privilege to play for Her Imperial Majesty and win her applause.83

It is assumed that the music played during the meal was Haydn's Symphony No. 48, nicknamed 'Maria Theresa', or perhaps even his Symphony No. 50. But since the report only mentions that music was a played, could divertimentos have been music performed on this occasion?

Eve Rose Meyer writes, “The pursuit of pleasure permeated all aspects of life in eighteenth-century Vienna, and music, long a part of Austrian tradition, provided a favourite form of amusement for both rich and poor, since all classes of society were enthusiastic in their devotion to music.”84 The famous singer Michael Kelly said when he visited the city, “Vienna was a place where pleasure was the order of the day and night.”85 A good example of a place of pleasure ‘were the lemonade huts that were set up all over the city. Kaspar Riesbeck describes this institution most vividly in 1780:

“One of the most beautiful spectacles for me during the late summer nights were the so-called lemonade huts. In the larger squares of the city, one sets up a large tents, in which lemonade is served at night. Several hundred chairs often stand around it and are occupied by ladies and gentlemen. A short distance away stands a robust band of musicians [...] The excellent music, the solemn silence, the confidentiality that the night instils in society. It all gives the performance a special touch.”86

The print, Der Gesellschaftsplatz auf der Burgbastei in Wien by Vincenz Raimund Grüner (1771-1832), depicts a lemonade stand at a social gathering spot. Figure 25 illustrates this detail.

Chapter 6

Manuscripts

The study of historical manuscripts played an important role in determining whether the double bass could have been the intended bass instrument in the Divertimento Sextet. This involved the examination of title pages and bass parts of the extant manuscripts. Should the term violone or contrabasso appear on a manuscript title page and/or bass part, this could indicate that the double bass was intended instrument. In a majority of divertimento manuscripts, though, the term ‘basso’ is used to refer to the bass line, which gives no indication of any specific instrument. Therefore, when this term is used, the range and lowest notes of the bass part must be examined to determine if the double bass was likely to be part of the ensemble. Bearing in mind that the double bass in 18th century Austria had a lowest note of either F1 or E1, should the range of the bass part in the manuscript fall below this, it may indicate that the double bass was not used. However, it is important to consider that there are exceptions to this rule, which underlines the importance of examining manuscripts to understand the intended instrumentation.

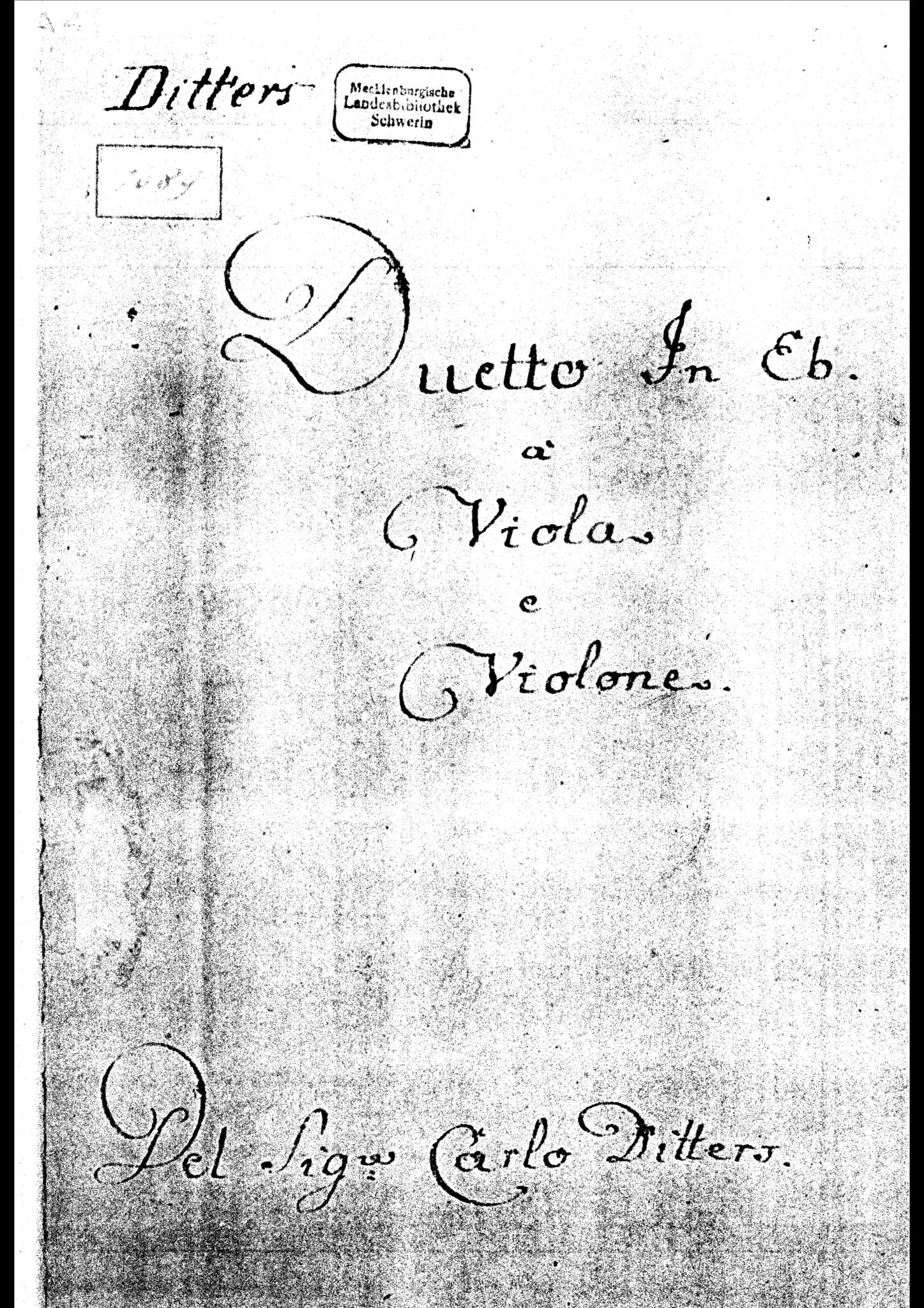

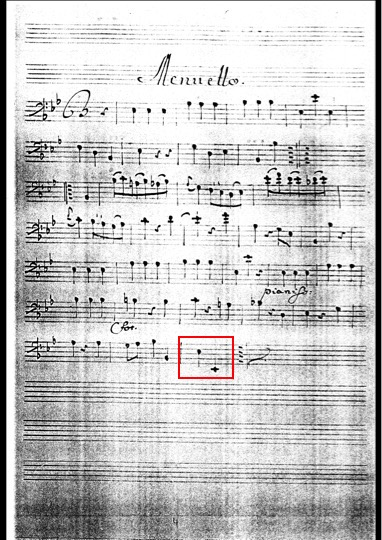

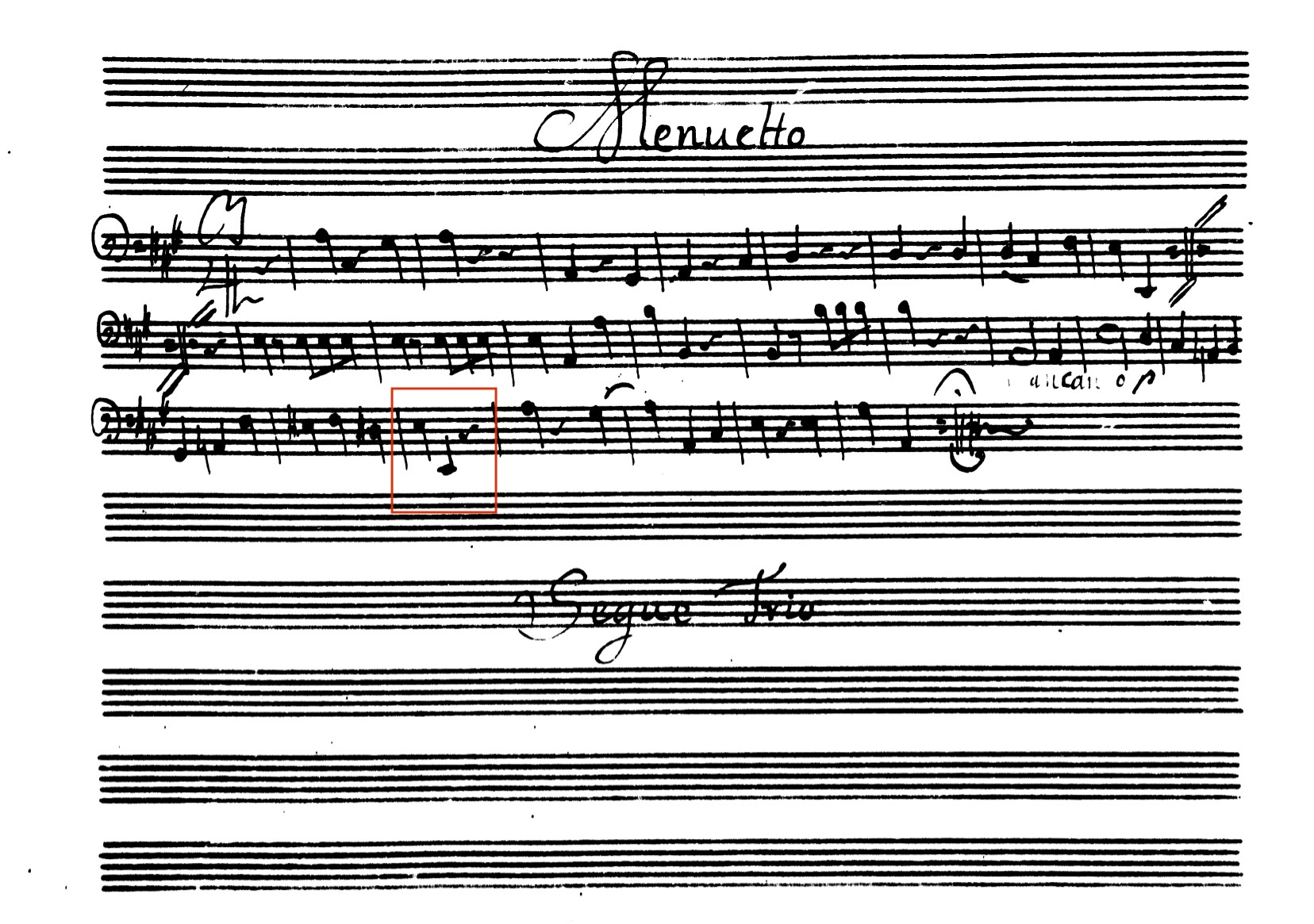

One such exception occurs in the Duetto for Violone and Viola, by Karl Ditters van Ditterdorf. He wrote this piece around 1769 for double bassist Friedrich Pischelberger when they both employed by Bishop of Grosswardein (now Oradea, Romania). The instrument Pischelberger used was the typical 5-string Viennese bass tuned F1-A1-D-f#-A. In the Menuetto the bass part reaches down to a low Eb1. This the only time in the entire piece that range extends lower than the lowest note of the double bass. How can this be explained? James Webster suggests that in such an instance the E-flat is on the weak beat of a cadence and could be considered a composer’s slip of the pen (Figure 26).87

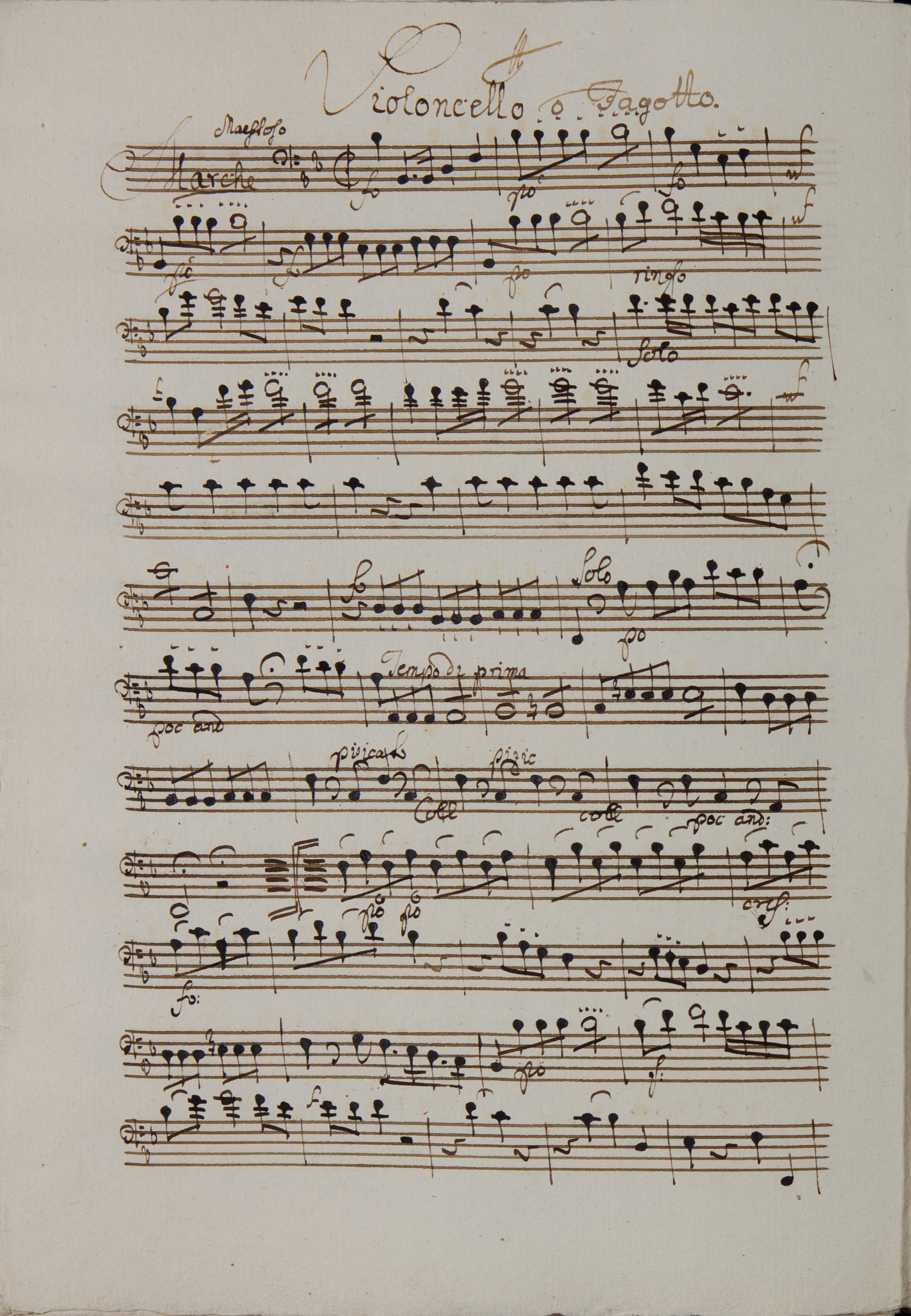

A similar example can be found in Vaclav Pichl's, Notturno for Violin, Viola, Violoncello, two Horns, and Basso. Pichl, who worked in Grosswardein from 1765 to 1769, also composed two concertos for the 5-string Viennese double bass. On the title page of the Notturno, the term ‘basso’ is used to designate the bass line, but the bass part is titled ‘Violone’, indicating that this particular instrument should play the bass line. However, in four instances in the violone part, the notes descend lower than F1, which raises questions as to why the composer wrote notes outside of the lower range of the double bass. Furthermore, the violone is not doubling the cello in these cases (Figures 27-31).

It is interesting to note that the violoncello part in question is entitled "Violoncello ó Fagotto", which suggests that it was originally intended for the violoncello but was later adapted for the Fagotto (bassoon) as well. The use of the word ‘ó’ in the title, which is Latin for ‘or’, further supports this idea. Also, the fact that the writing seems to be by a different hand could indicate that the piece was popular or flexible enough to be adapted to different instrumentation. Further research into the history and compositional origins of the piece could possibly shed light on the reasons for this adaptation and the cultural and musical context in which it took place (Figure 32).

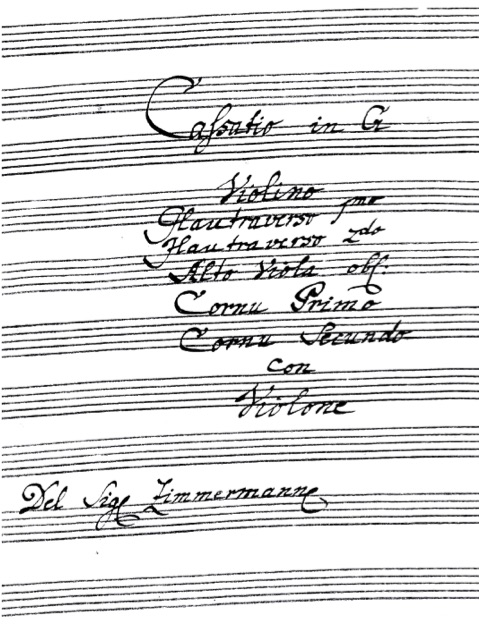

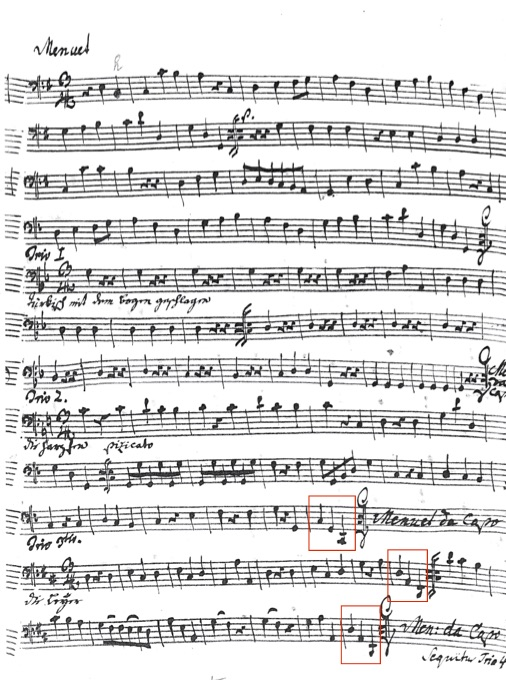

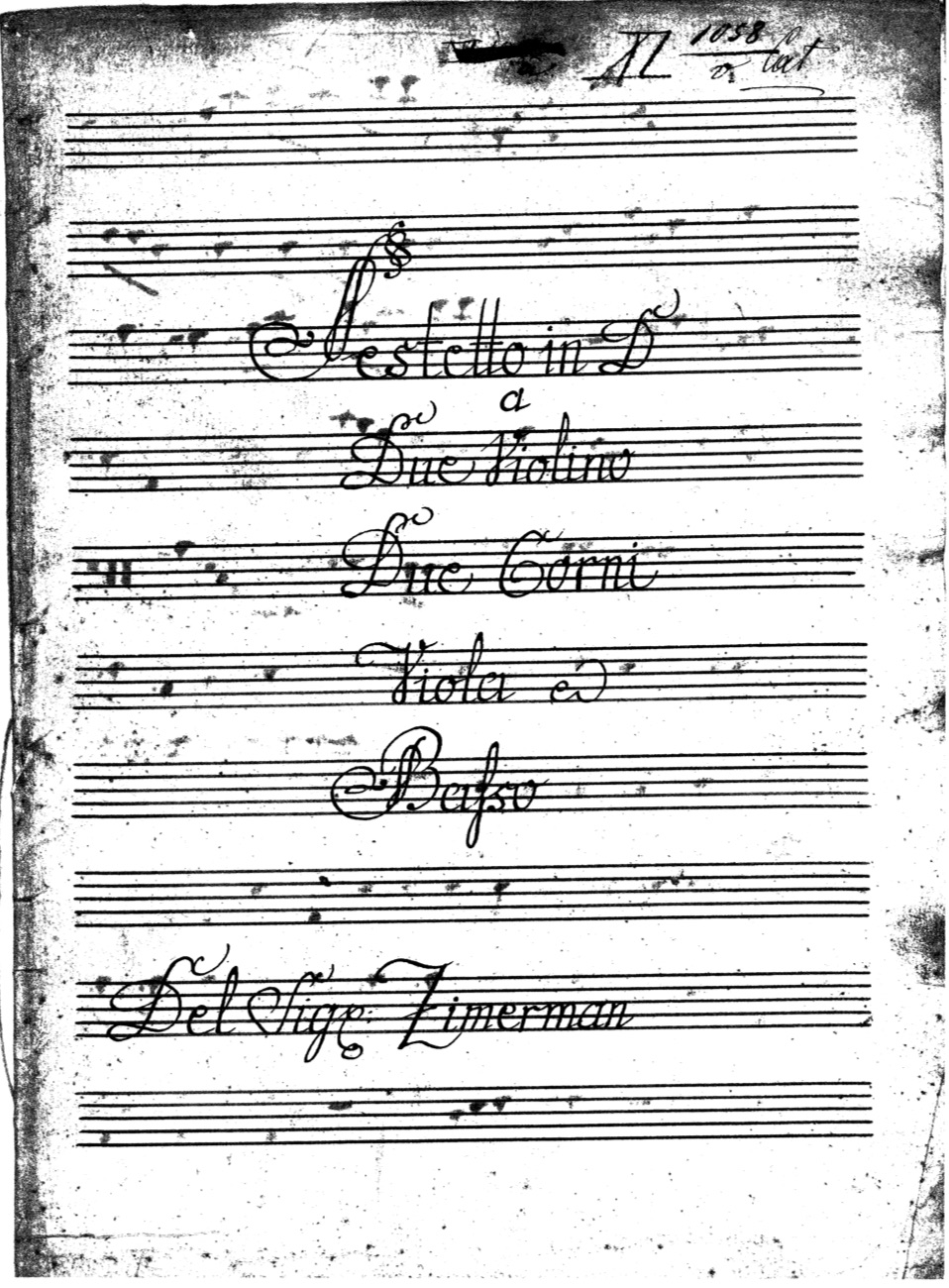

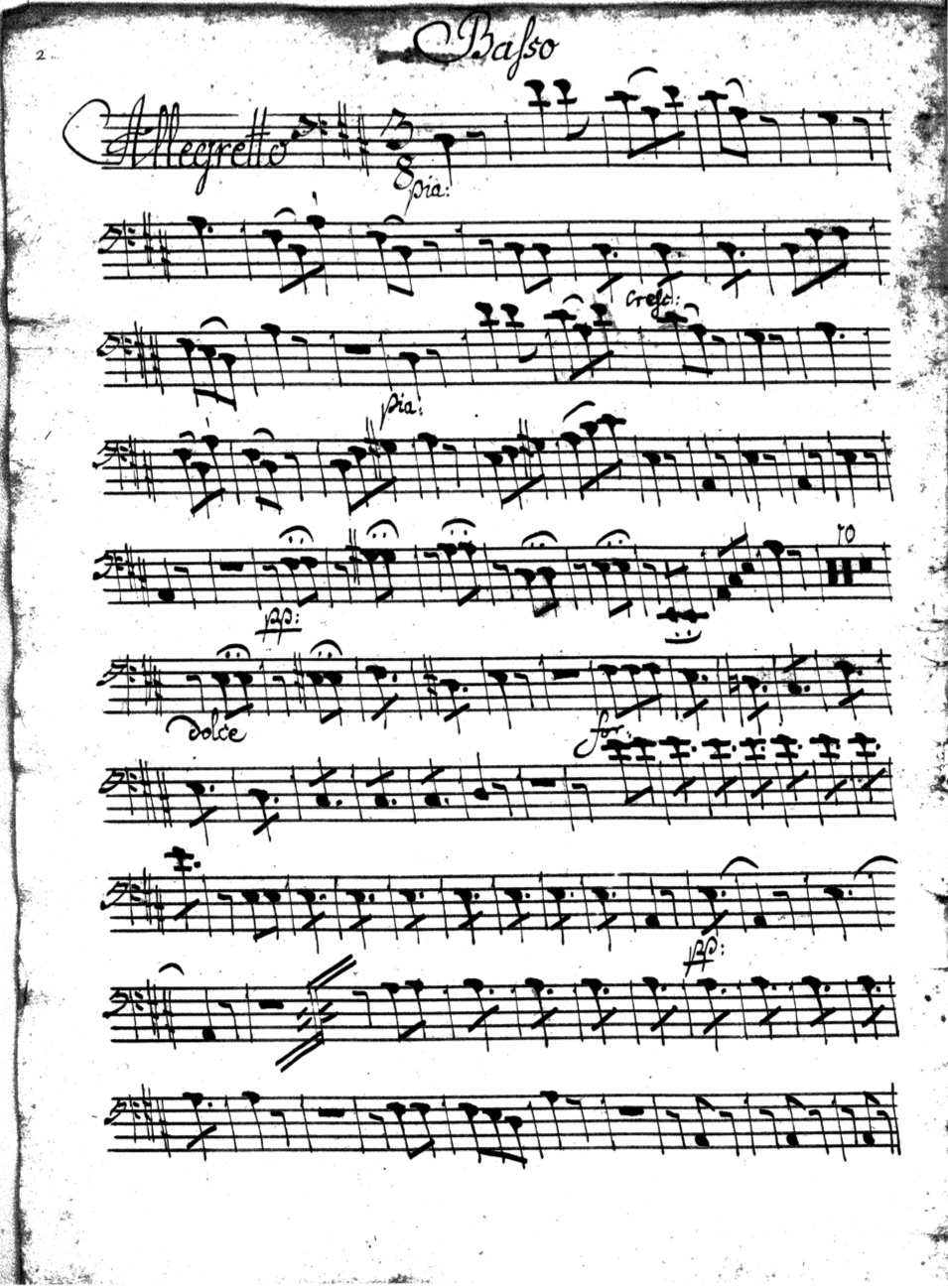

Another example is from a Cassation for Violin, 2 Flutes, Viola, 2 Horns, and Violone by, Anton Zimmermann, which is housed in the library of Kremsmünster Abbey in Upper Austria. On both the title page and the bass part, the term ‘violone’ is used to indicate the bass instrument. There are eight instances in the piece where the notes in the violone part go lower than F1, even down to low C1, all of which occur on weak beats in a cadence. At the time the piece was composed, Zimmermann held the position of Kappellmeister (director of music) in the service of Cardinal Joseph Battyány, in Pressburg (now Bratislava) from 1773 until his death in 1781. The virtuoso bassist Johann Mathias Sperger (1750-1812) was also employed there from 1777 until the ensemble was disbanded in 1783. It is known that Sperger only played in the (Viennese) tuning of F-A-D-f#-a in his lifetime. This raises the question of how these notes below F1, especially the low C1, can be explained. Most likely the piece was written in Pressburg and then copied for use at Kremsmünster. It remains uncertain whether the violone at Kremsmünster was tuned down to low C1 or if Zimmermann simply wrote the bass line without regard for the tuning of the violone. Notably, Trio 1 of the Menuet is indicated as ‘mit dem Bogen geschlagen’...'hit with the bow', a specialty bassists!(Figure 33).

Figure 33 Title page and Menuet of Violone part from Zimmermann’s Casatio in G

A Serenata in F by, Dittersdorf for two violins, two Violas, two Horns and Bass housed in the library in Prague could be considered an expanded version of the Divertimento Sextet. The bass line is marked ‘Basso’ on the title page and the playing part is marked ‘Violone’, so it is clear which instrument is to play the bass line. Only in one case does the bass line reach lower than the instrument's range, and that is on the weak beat of a cadence (Figures 34-36).

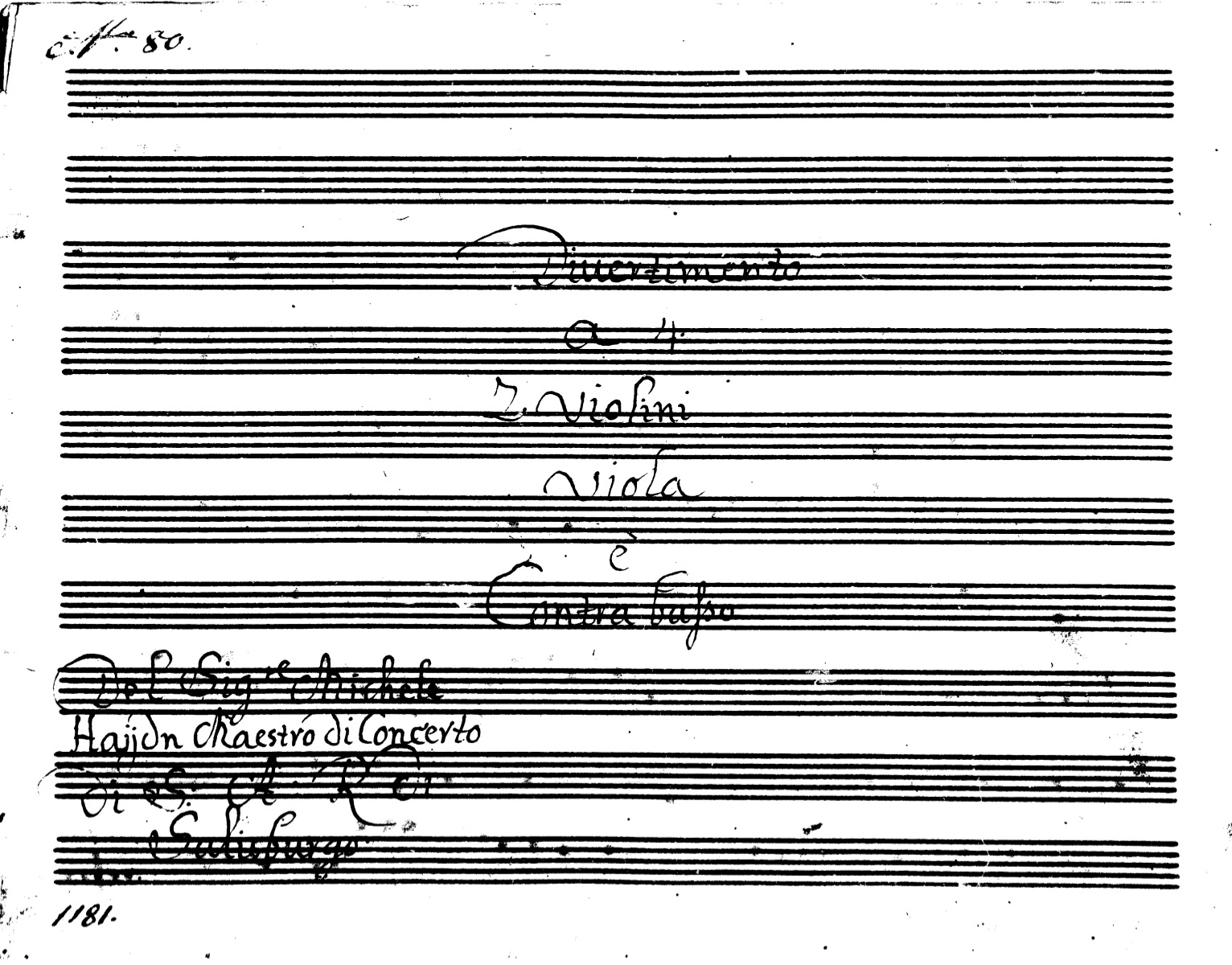

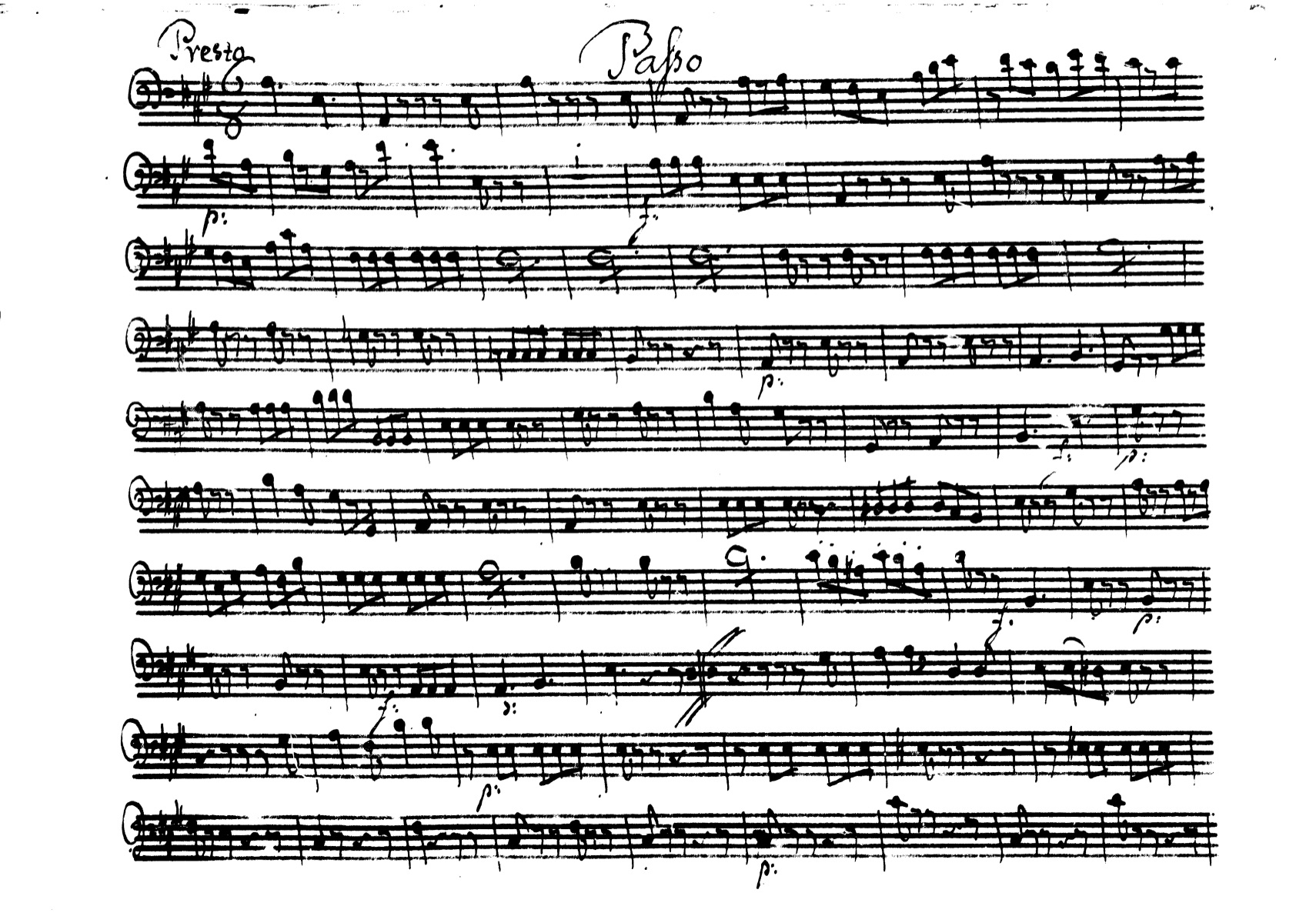

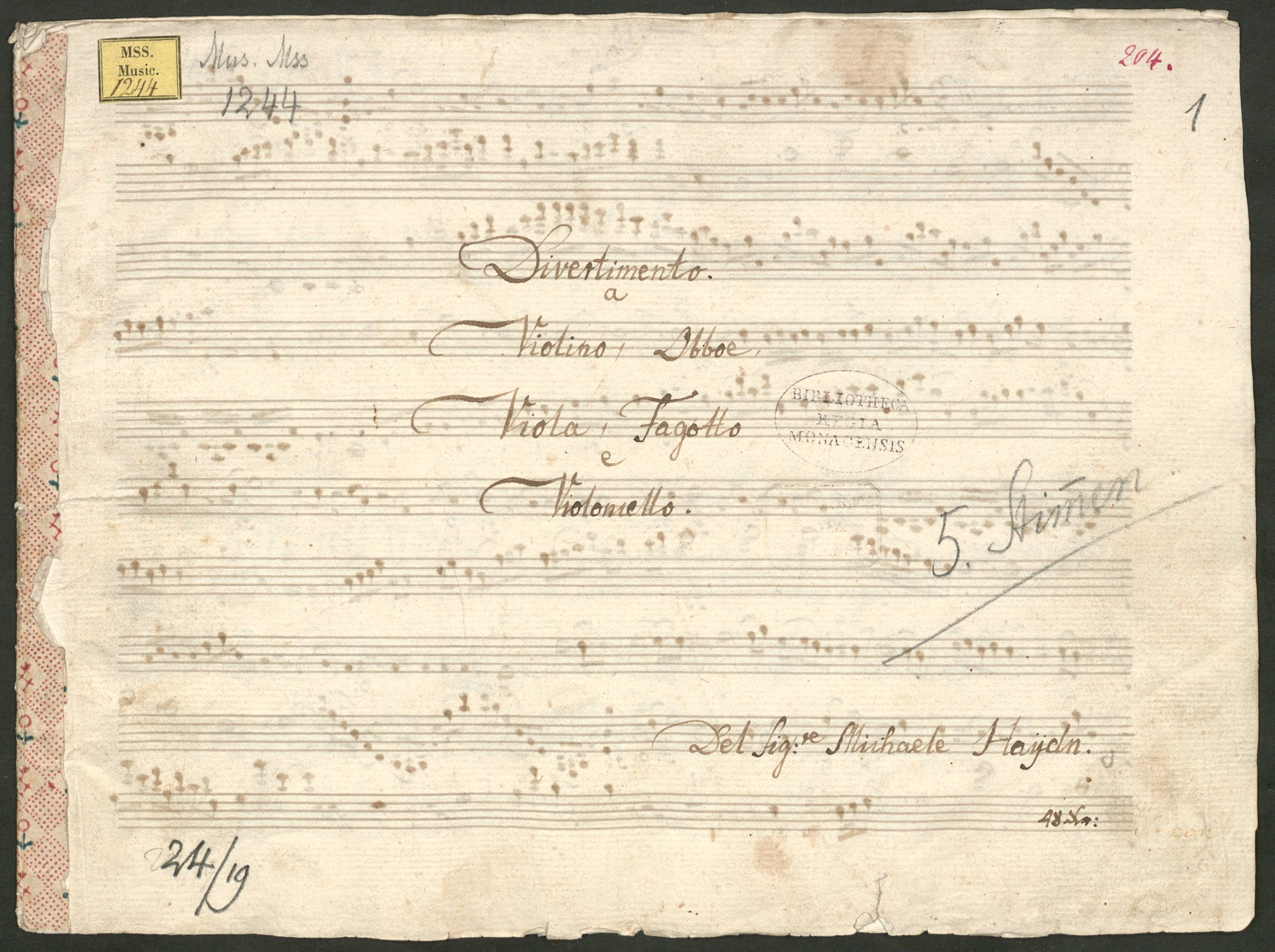

The Prague library also houses a Divertimento by Michael Haydn for the instrumentation of the Divertimento Sextet. The title page of the manuscript refers to the bass line as ‘Violone’, but the bass part is labeled ‘Basso’. There are four instances in the manuscript where the bass line extends beyond the lower range of the double bass. Another manuscript of this piece is also held at the library of Kremsmünster Abbey, but bears the title "Notturno", and unlike the Prague manuscript, both the title page and bass part are labeled ‘Basso’ (Figure 37).

Prince Kraft Ernst of Oettingen-Wallerstein (1748-1802) was known for maintaining one of the most impressive musical establishments in Europe. He devoted a significant portion of his wealth to supporting his Kappelle as illustrated in Silhouette of the Harmonie (with double bass) at the court of Oettingen-Wallerstein. (Figure 38) Today, a large collection of his music manuscripts can be found at the University of Augsburg in Southern Germany. This collection includes two particularly noteworthy manuscripts by Michael Haydn: a Divertimento a 4 for two violins, viola, and contrabasso in A major and one in D major. The instrumentation is similar to that of a string quartet, but with a double bass replacing the cello. On the manuscripts, Haydn is listed as ‘Maestro di Concerto di Salisburgo,’ which translates to ‘Concert Master of Salzburg’. In the Divertimento in A major, the bass line is labeled as ‘Contrabasso’ on the title page and on the part, ‘Basso’ with the lowest note in the bass part being an E1. This note corresponds to the lowest pitch of a 4-string double bass commonly used in Salzburg during the 18th century. (Figure 39) In the Divertimento in D major, both the title page and the bass part refer to the instrument as ‘Contrabasso’, with the lowest note in the bass part being an F#1 (Figure 40).

An example of a composition written for the Divertimento Sextet instrumentation is the Cassatio in D major by, Johann Baptist Vanhal, which is housed in the library in Prague. The manuscript uses the term ‘Basso’ on both the title page and bass part, but this does not necessarily indicate that the piece was written specifically for the double bass. The bass part is relatively simple and does not extend below G1, which is within the range of the double bass. However, it's worth noting that the key of the piece might have influenced the range of the bass part, and thus, the specific instrument it was intended for cannot be determined with certainty (Figure 41).

Figure 41 Title page and Basso part, Cassatio in D, G.B. Vanhal

Another example of a piece with the Divertimento Sextet instrumentation is the Serenata in G by Dittersdorf, which is housed in the manuscript collection of the University of Wrocław, Poland. In this case it is titled with one of the alternative names for a divertimento, ‘Serenata’. In the Menuetto, the bass part reaches down to a D1. This is the only time this occurs in the piece, again on a weak beat. Curiously, 24 bars later, the same figure is repeated an octave higher, while the other string parts remain in the same octave (Figure 42).

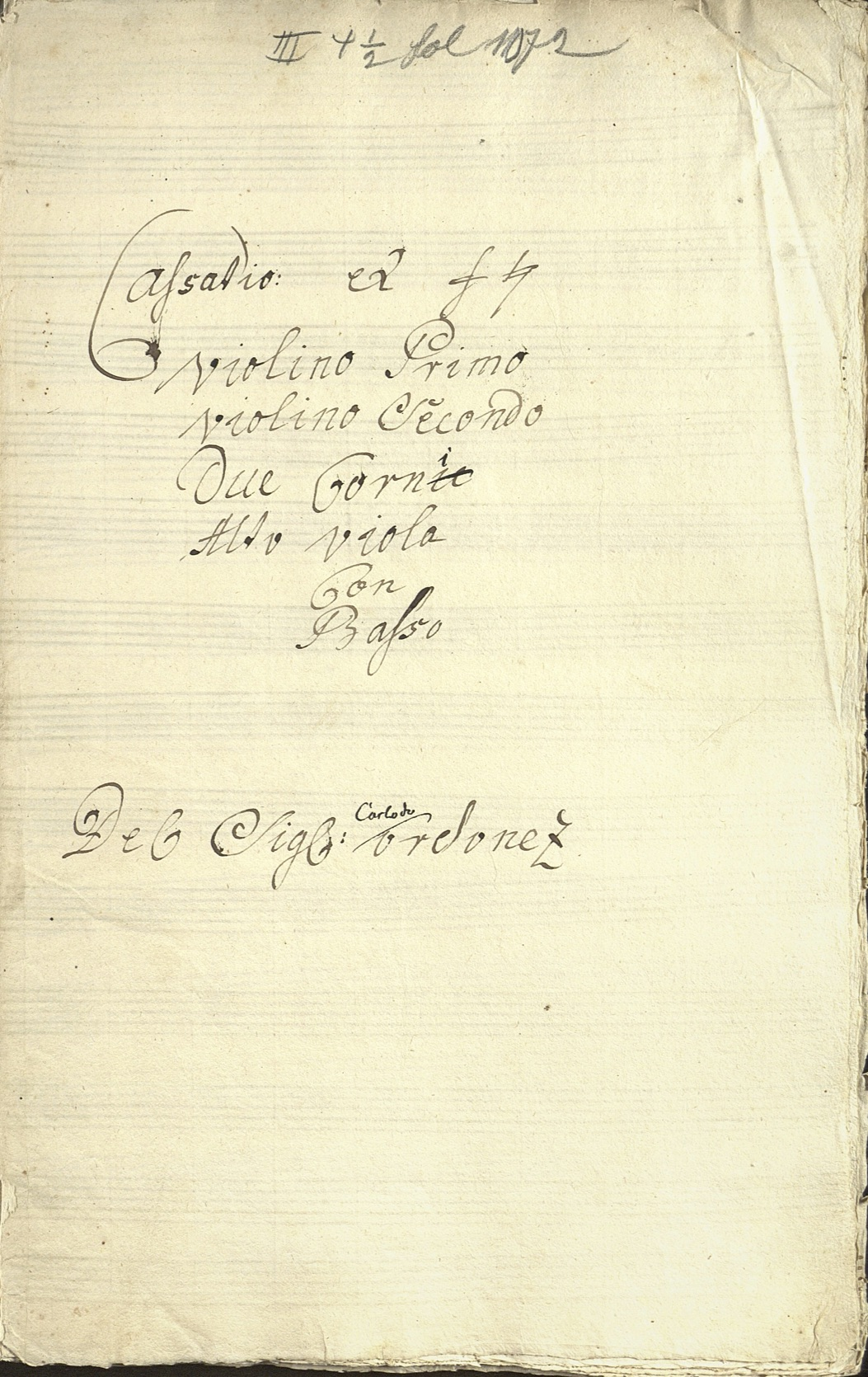

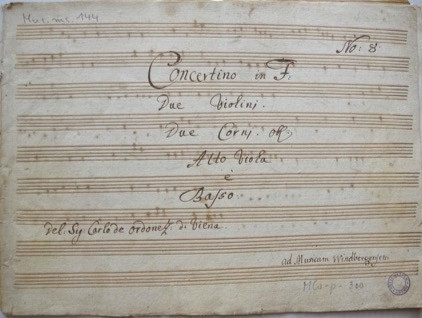

Carlos d'Ordoñez (1734-1786) was a minor composer living in the era of Mozart and Haydn. While his full-time profession was as an administrator at the Lower Austrian Regional Court, he also played the violin in the Kaiserliche Kammermusik and the Tonkünstler-Societät. He composed several symphonies, string quartets, and divertimentos. The example provided here is of a piece that shares the same instrumentation as the Divertimento Sextet. During my research, I found manuscripts of the piece in three libraries under different titles: ‘Sextetto Concertino’, ‘Concertino’, and ‘Cassatio’ (Figure 43). Notably, all three versions had the term ‘Basso’ featured on their title pages and bass parts. The bass part of the piece does not extend lower than F1, which is also the lowest note playable on a 5-string Viennese bass. Given the fact that F1 is the lowest note, this does not necessarily mean that the piece was specifically composed for this instrument. Other factors, such as the key of the piece, can also affect the range of the bass part.

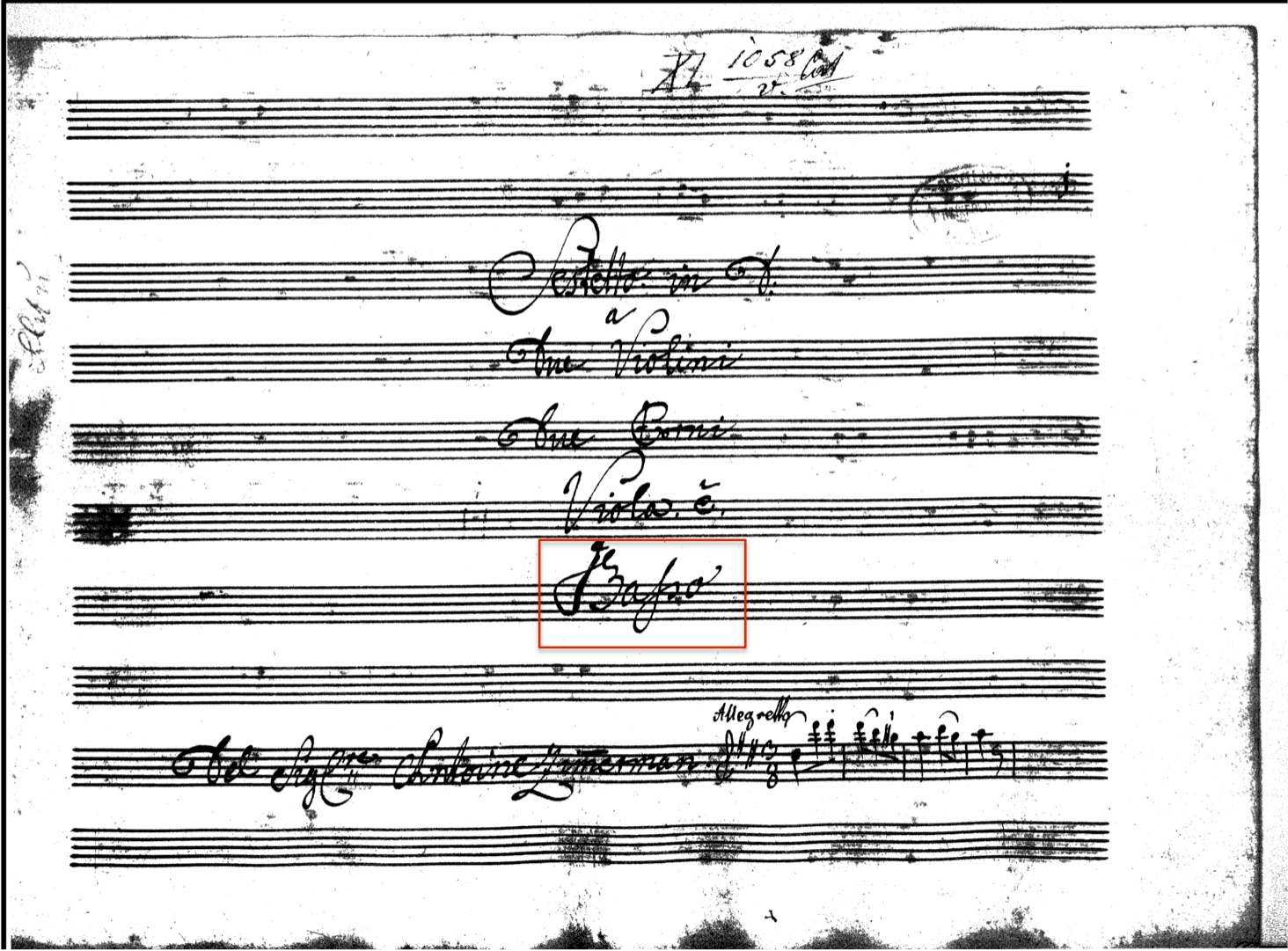

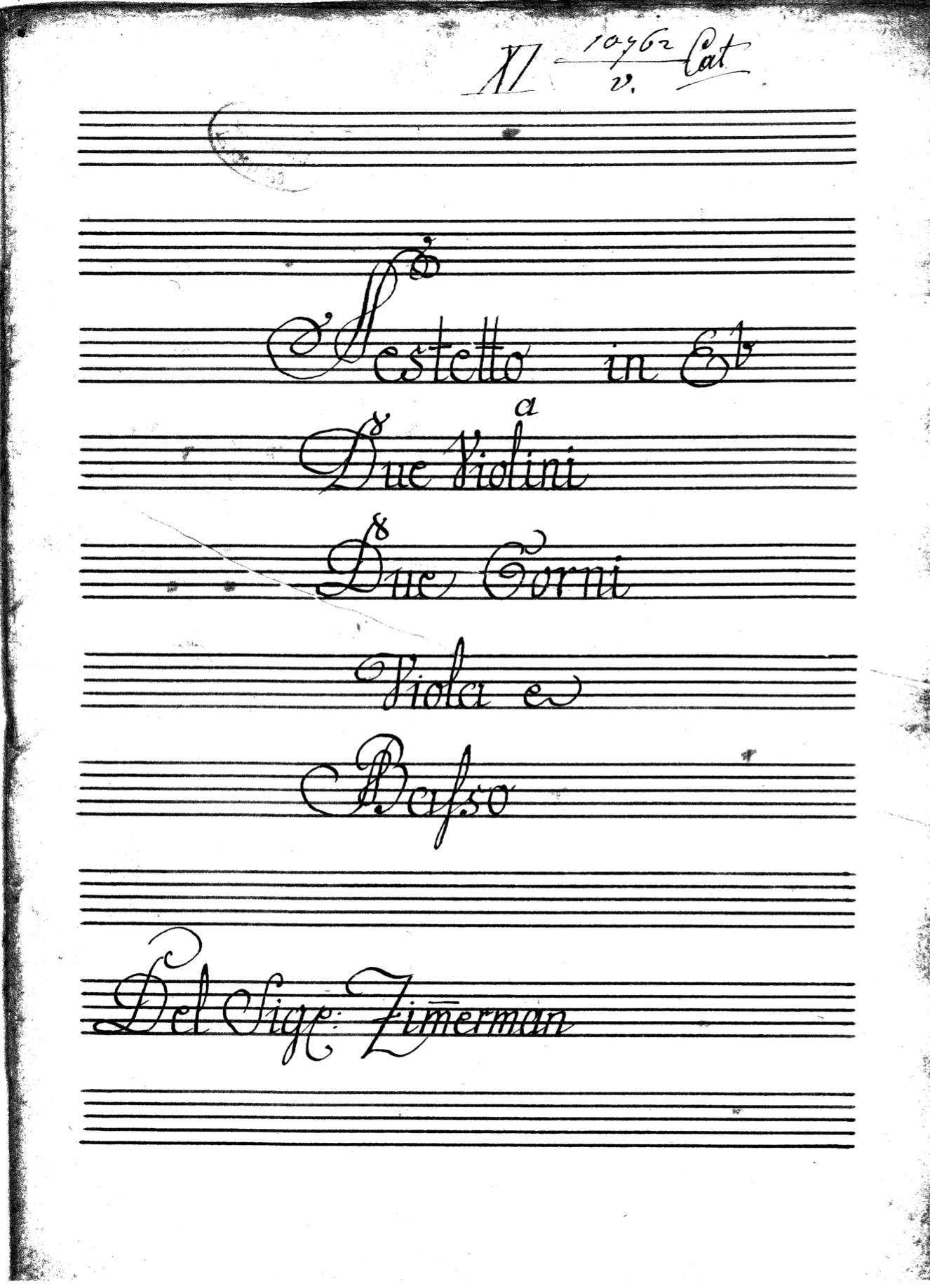

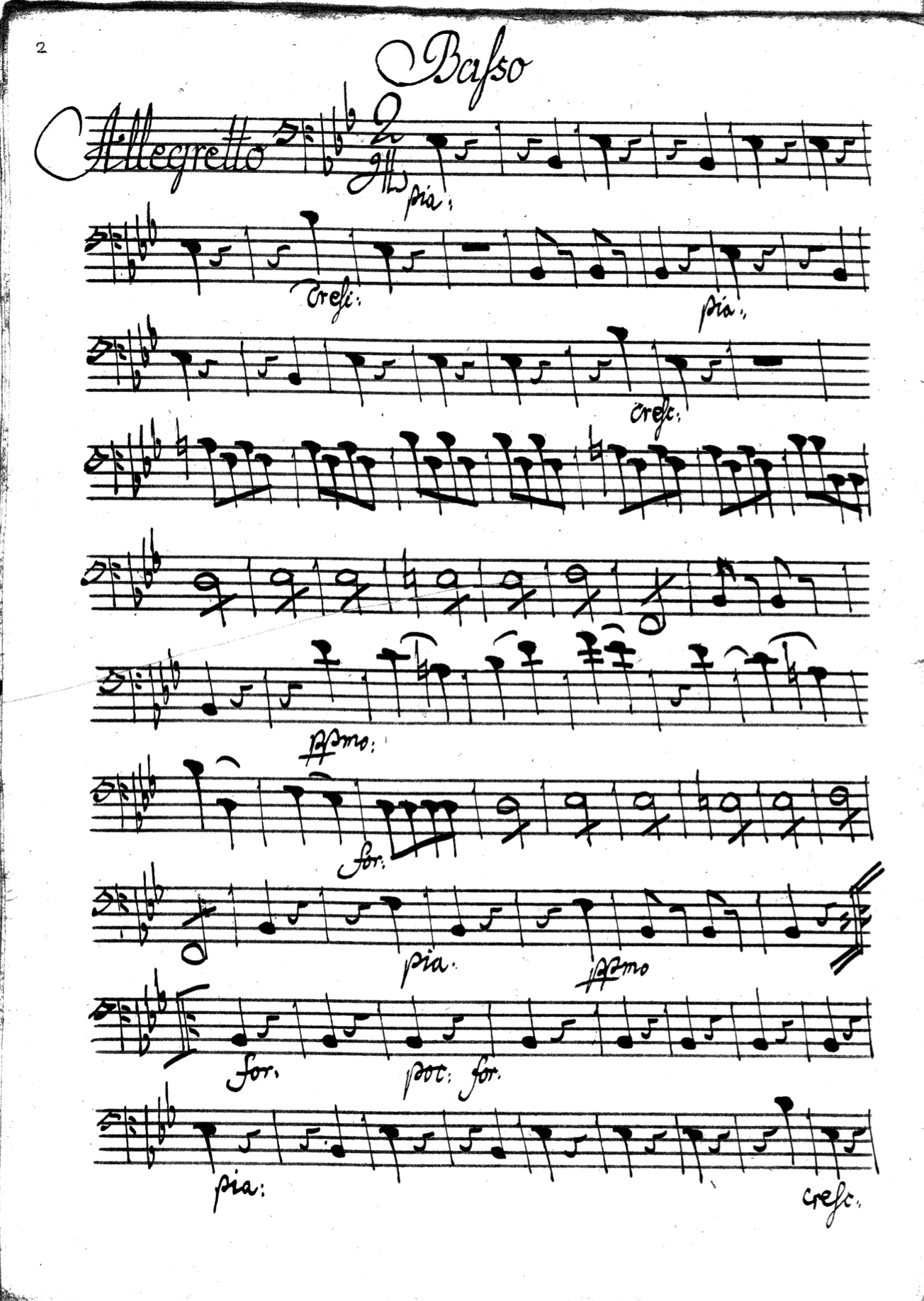

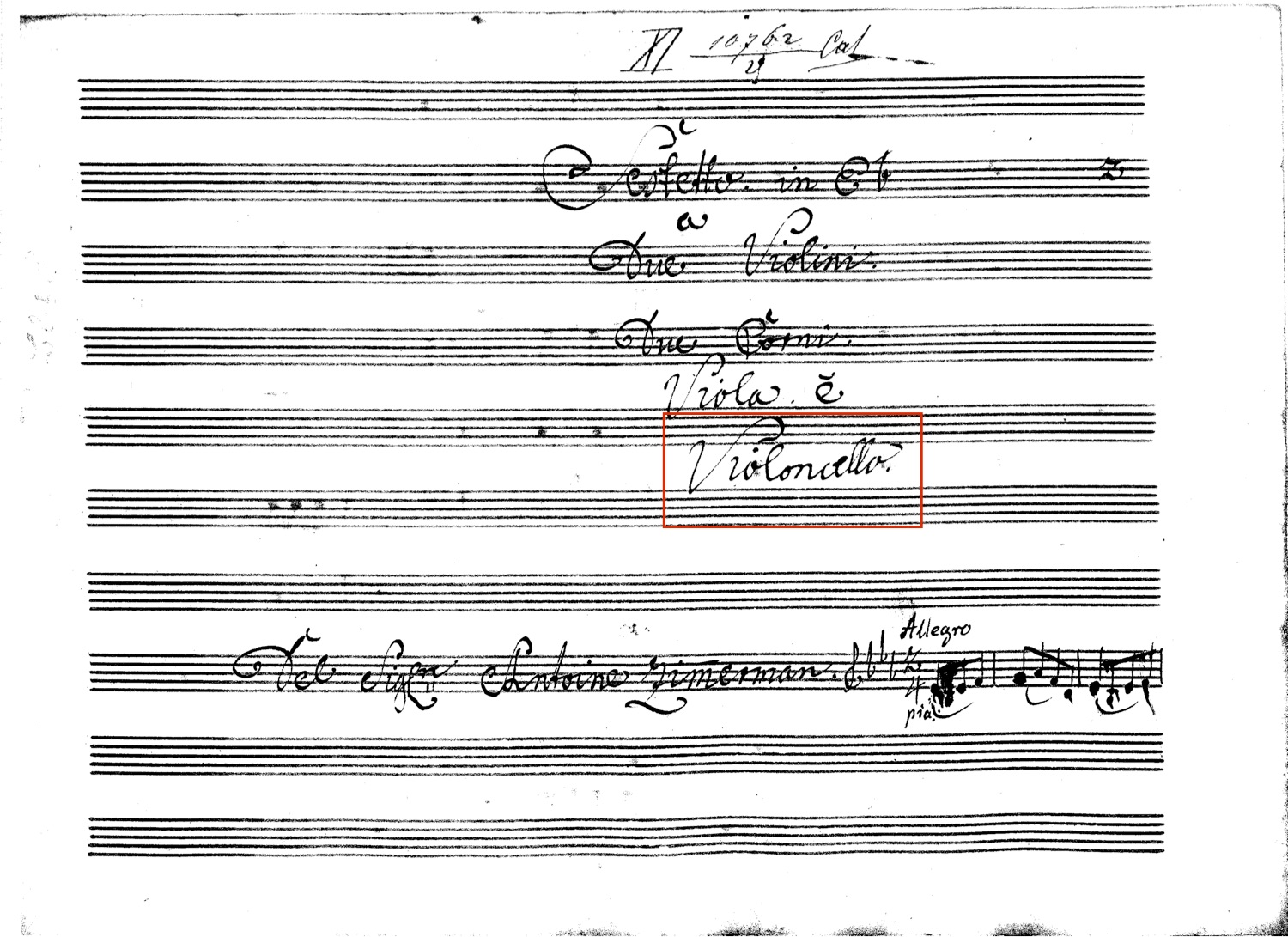

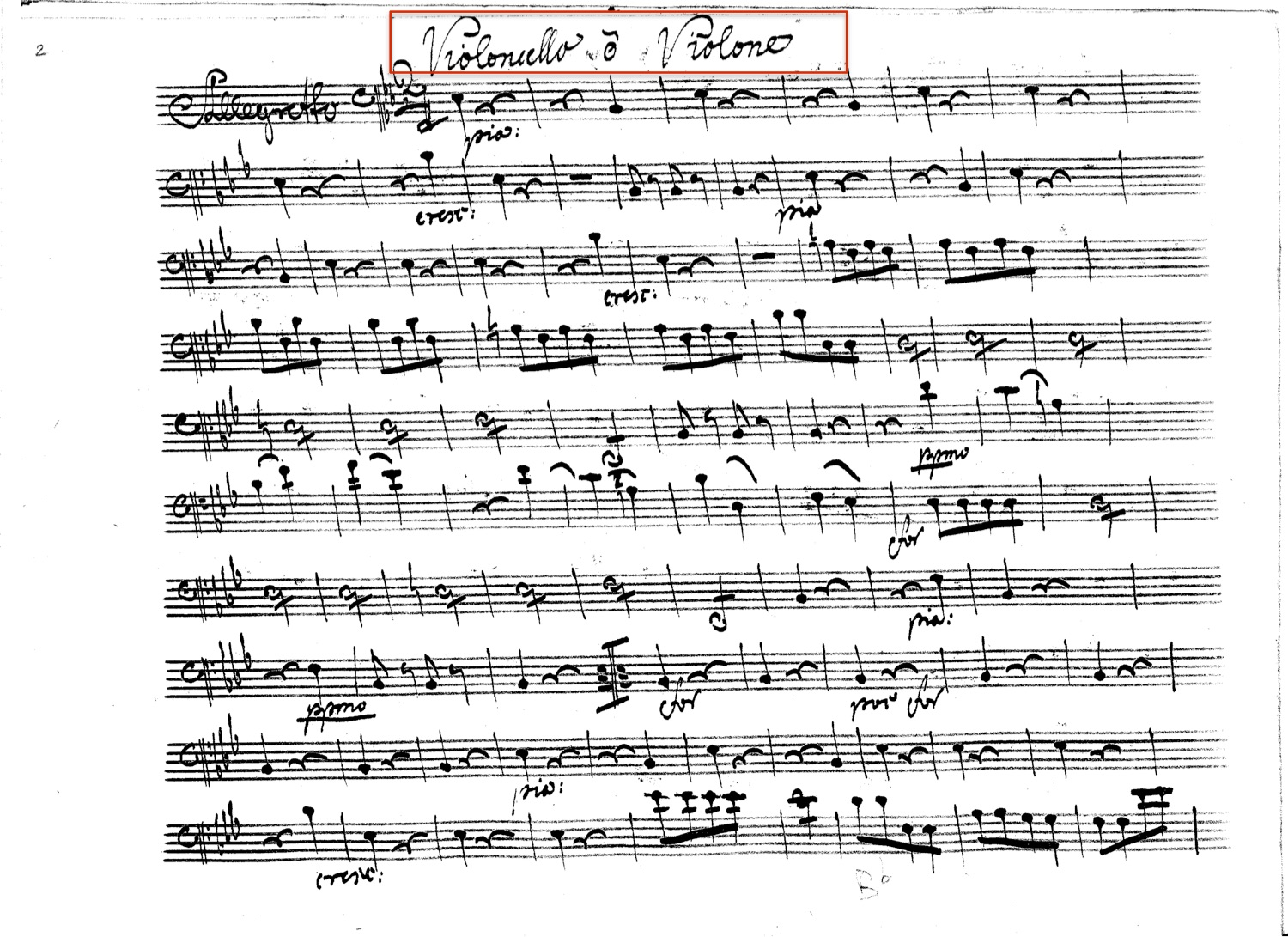

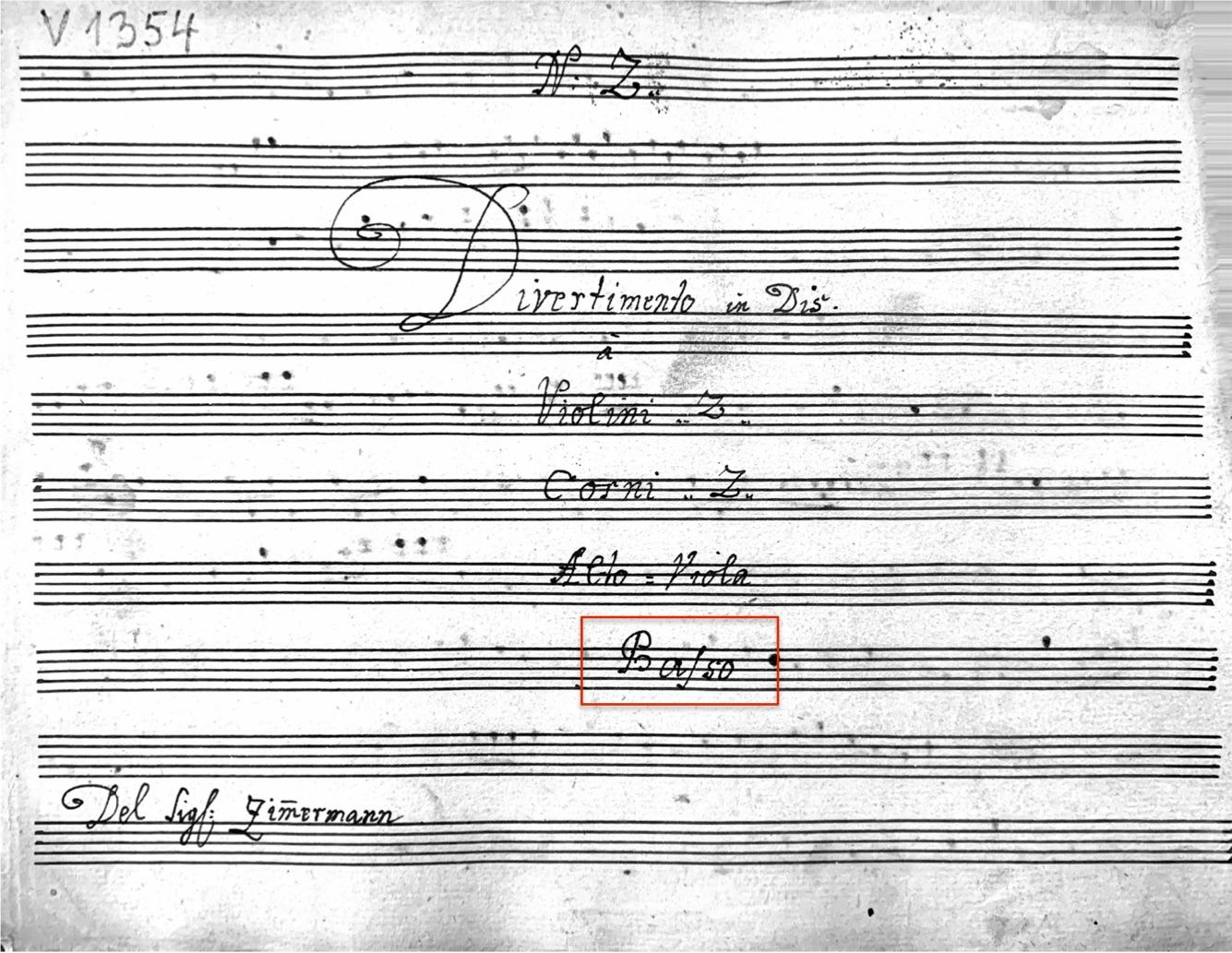

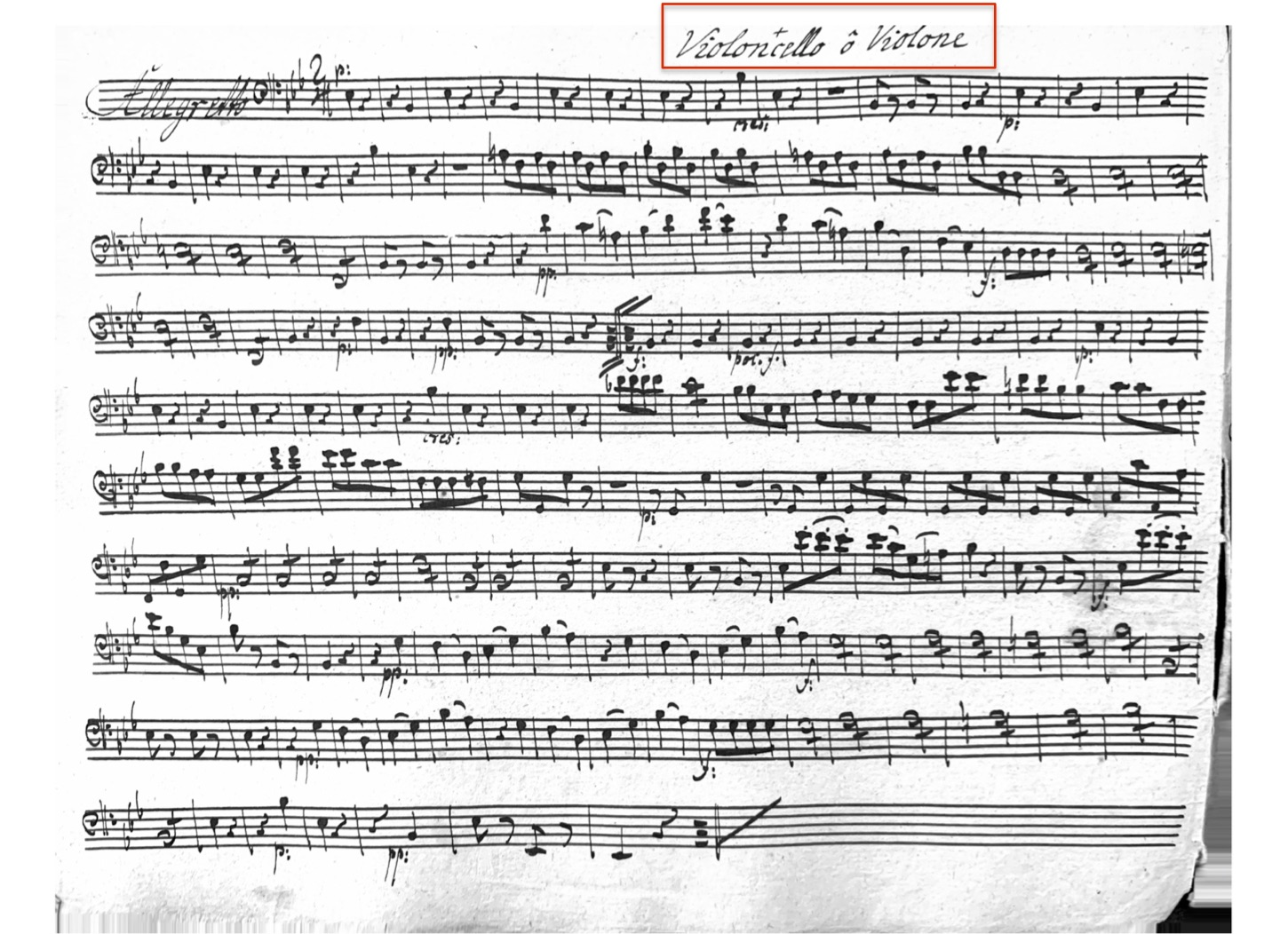

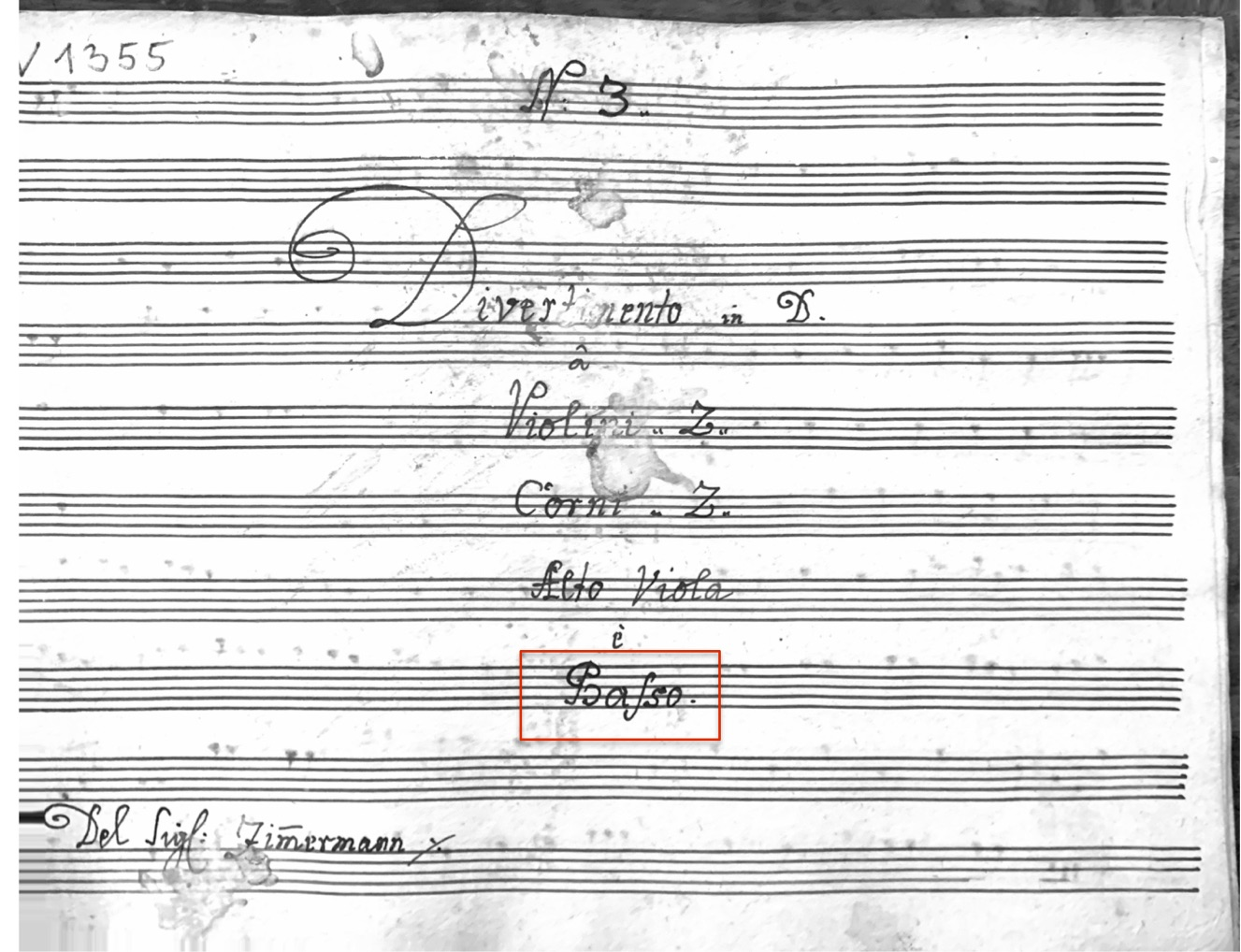

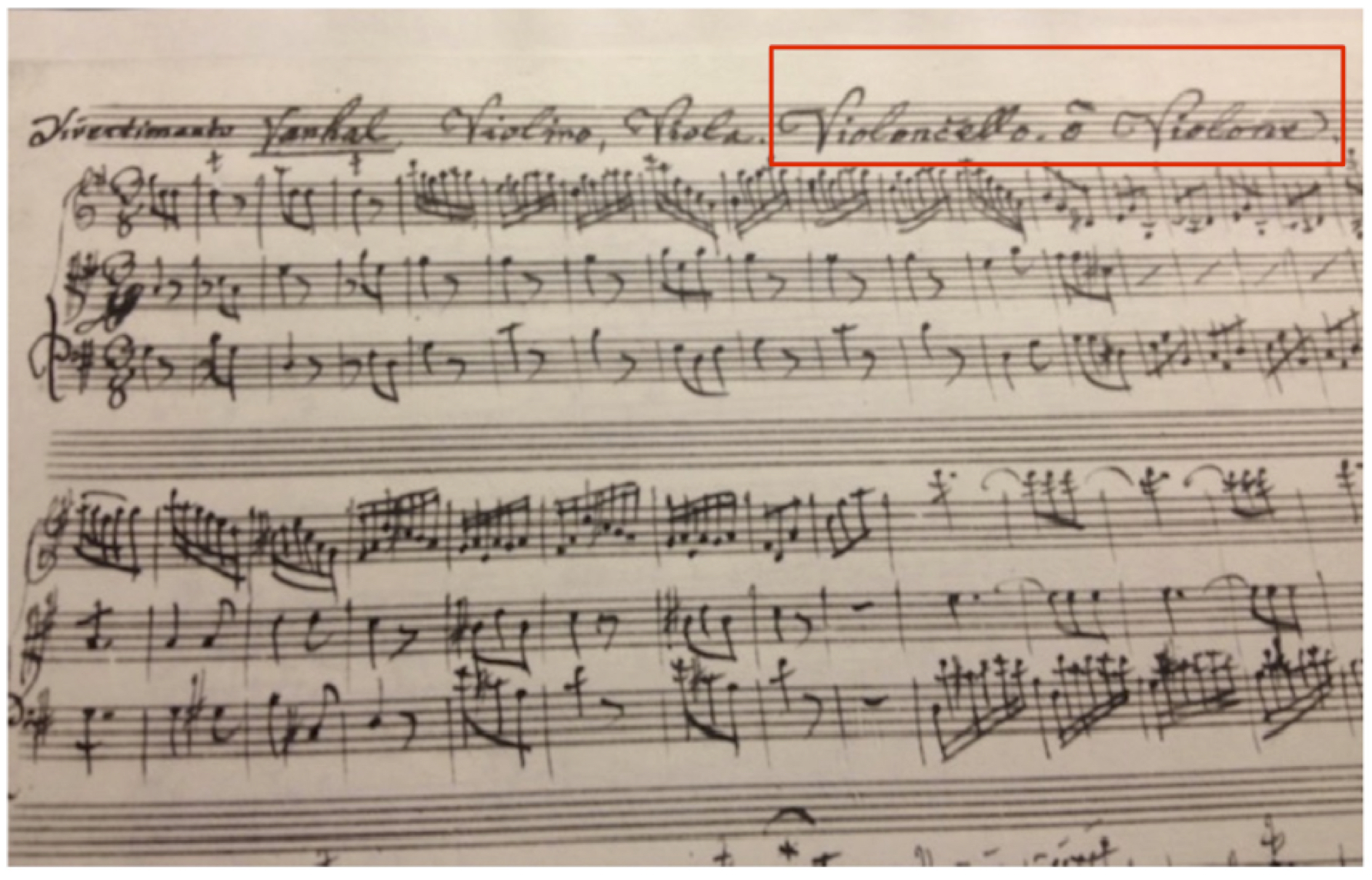

Anton Zimmermann composed several sextets with the scoring of the Divertimento Sextet. Two manuscripts are preserved in the library of the Musikverein in Vienna, which bear the title ‘Sestetto’. In both sets there is a title page and a bass part that are written out on vertical paper (Figure 44). In both sets the term ‘Basso’ is used to refer to the bass instrument both on the title page and in the bass part. Additionally, there is a title page and all the playing parts written out on horizontal paper. On the horizontal title page of the Sestetto in D major the term ‘Basso’ is used for the bass instrument and on the bass part the term ‘Violone’, great news (Figure 45)! My heart sank when I looked at the manuscript of the Sestetto in E-flat, for on the title page the bass instrument was indicated with the term ‘Violoncello’, but, I was thrilled and relieved when I got to the bass part and saw that the terms ‘Violoncello ó Violone’ were used, implying that either instrument could perform the part (Figures 46 and 47).

The library of the Seitenstetten Abbey houses six Divertimento Sextets by Zimmermann, including the two that can also be found in Vienna. I have succeeded in obtaining copies of five of these sextets, including the Divertimento in D and E flat. In contrast to the Viennese copy, the title page of the Divertimento in D major designates the bass as ‘Basso’, but the bass part uses the designation ‘Violoncello’ (Figure 48). Also in contrast to the Viennese copy, the title page of the Divertimento in E-flat major designates the bass as ‘Basso’, but the bass part uses the designation ‘Violoncello ó Violone’ (Figure 49). The Divertimento in E-flat major is the only one of the five Seitenstetten manuscripts that uses the designation ‘violone’. Examination of the bass parts shows that all five manuscripts have a range that extends lower than F1. The Divertimento in E-flat has 13 instances of this, the most of all the divertimentos, and is interestingly the only one that bears the term ‘Violone’.

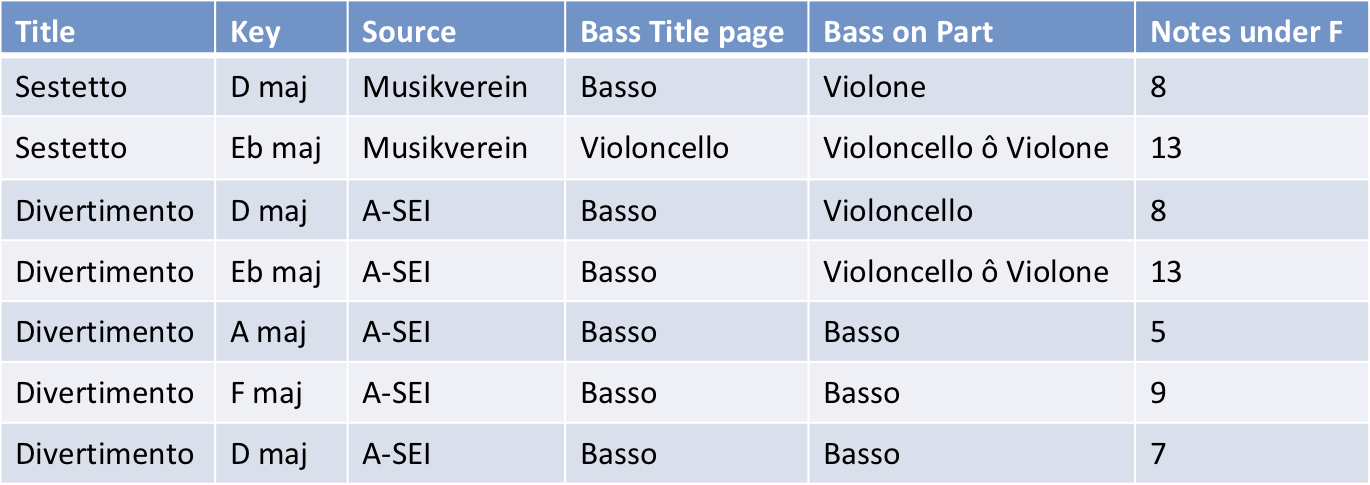

The following is an inventory of Anton Zimmermann's Sestetto and Divertimento compositions with the instrumentation of the Divertimento Sextet found in the libraries of the Vienna Musikverein and the Seitenstetten Abbey. The inventory includes an examination of the nomenclature used on the title pages and playing parts of these compositions. In addition, the bass parts are analyzed, focusing on the frequency of instances in which the notes extend below the pitch F1.

Table 2

The interchangeable usage of the terms violone, violoncello, and basso is demonstrated in the following examples. One such example is the Divertimento in G composed by Johann Baptist Vanhal, which is suitable for performance by a combination of violin, viola, and either a violoncello or a violone. This illustrates the fluidity and flexibility in the designation of these instruments in the musical context of the 18th century (Figure 50).

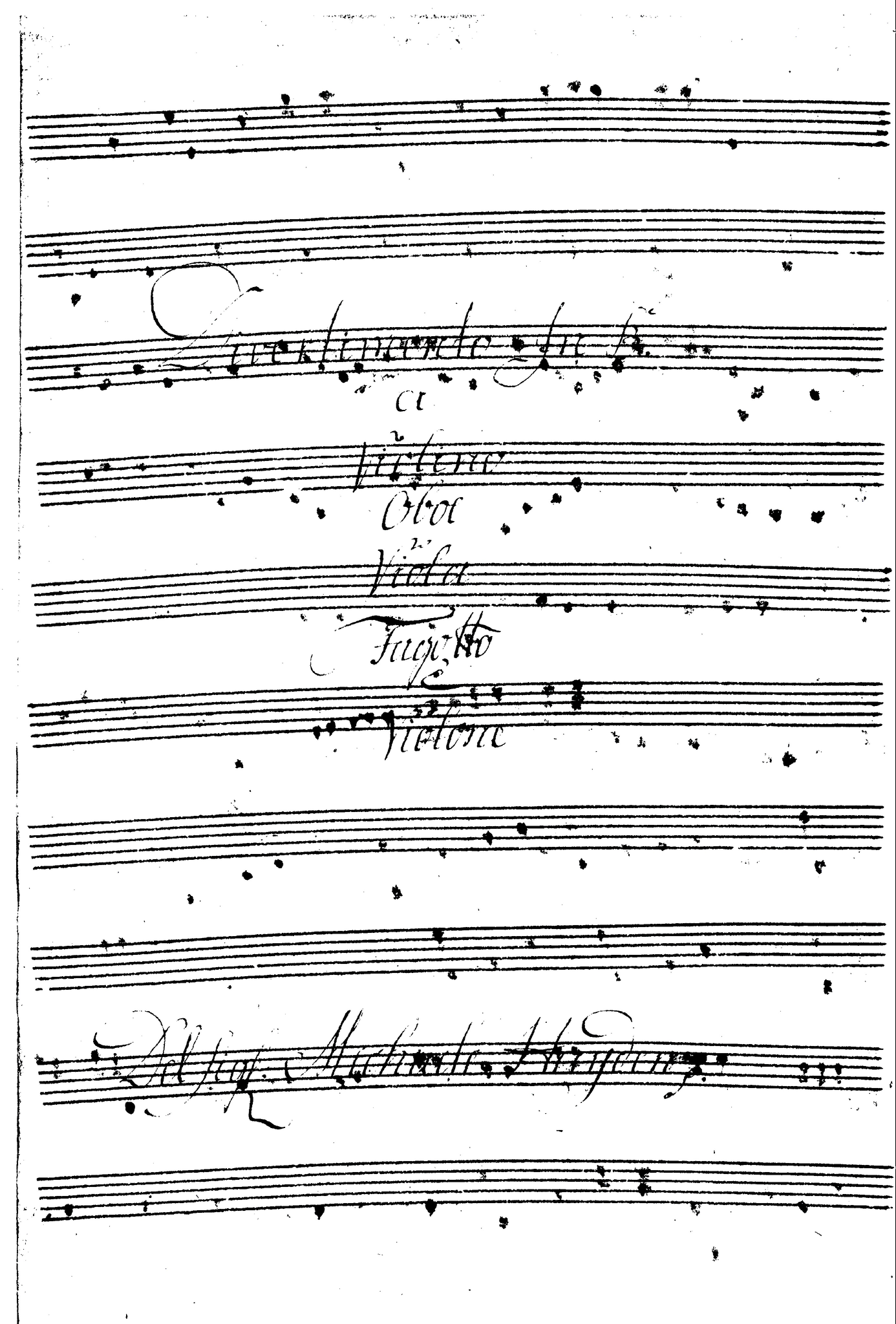

The Divertimento in B-flat for Violin, Viola, Oboe, Bassoon and Violone by, Michael Haydn appears to have been a very popular piece, as evidenced by the existence of several manuscript copies in various libraries such as Kremsmünster, Munich, Prague and Budapest. It is noteworthy that each of these copies has distinct variations in terms of title page and instrumentation, which further underlines the great popularity and use of the piece (Figure 51).

-

Kremsmünster A-KR Divertimento for Violin, Viola, Oboe, Bassoon and Violone

-

Munich D-Mbs Divertimento for Violin, Viola, Oboe, Bassoon and Violoncello

-

Prague CZ-Pu Divertimento for Violin, Viola, Oboe, Bassoon and Basso

-

Budapest H-KE Quintetto for Violin, two Violas, Bassoon and Violone

The table below lists a collection of Divertimento Sextets, including the Zimmermann sextets from Vienna and Seitenstetten. It provides information on the terms used to label the bass line on the title page and bass part, the lowest notes in the bass line, and the number of instances where these notes fall below the typical range of the double bass in 18th century Austria (F1). Additionally, it records the number of times these notes occur on the weak beat of a cadence.

Table 3

Through examining these manuscripts, I have made a number of observations that will help me conclude whether the double bass could have been the standard bass instrument in the Divertimento Sextet. I have noticed that there are a variety of titles used for divertimentos, even for the same piece. Additionally, since the lowest note of the double bass in 18th century Austria was either F1 or E1, it was essential to examine the manuscripts to see how the bass part behaved in relation to notes lower than the range of the double bass. I have come across works in which the term Violone appears on the title or in the bass part in which the bass line extends lower than the range of the double bass, practically all on the weak beats of a cadence, raising the question if this could have been a “composer's slip of the pen”. I have also found works with only Basso on the title page and bass parts with notes extending lower than the range of the double bass. Further there were works with only Basso on the title page and bass parts with notes not extending lower than the range of the double bass. This does not necessarily mean that these pieces were specifically written for double bass, but that the notes could have stayed in a certain range due to the key in which the piece was written. I have discovered compositions with Violoncello ò Violone in the title page or on the bass part, as well as manuscripts from various libraries in which one source refers to the work as Violoncello and another as Violone, indicating that either instrument may be suitable for performance of the piece.

In the preceding section, several manuscripts have suggested that either a double bass or a cello can perform the bass line. To further illustrate this point, the following videos feature the 1st, Allegro, and 3rd, Adagio, movements from Joseph Haydn's Divertimento in E-flat Hob. II: 21. These demonstrations illustrate how the choice of bass instrument can impact the overall sound of the ensemble. It is worth noting that during the Adagio the horns are silent, which leads to the ensemble with a cello being similar to what is called a ‘string quartet,’ while the use of a double bass leads to what Carl Bär calls the ‘serenade quartet.’

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to determine if the double bass was the standard bass instrument of the Divertimento Sextet. In order to discover this I had to look in depth what the divertimento actually was. The first part of this study therefore examined this, and the second part investigated what the appropriate bass instrument would have been.

The term divertimento has historically been associated with light entertainment or background music. Between 1750 and 1780, various terms were used as titles for instrumental music, often interchangeably. However, during this time, the term divertimento emerged as the most commonly used title for Austrian chamber music, in a variety of instrumentations and styles. As a title, ‘Divertimento’ referred to instrumental music intended for one player per part, regardless of the specific instrumentation or style.

The designation of the bass line in divertimentos with the ambiguous term basso presented a challenge in determining the appropriate instrument for this part. During my early musical studies, I was under the impression that in chamber music the cello served as the standard bass instrument, with the possibility of doubling it with a double bass depending on the music. However, my participation in the divertimento project in 2000 caused me to question this assumption, as the idea of using only a double bass as a bass instrument seemed remarkably innovative. In particular, the Erste Londronishe Nachtmusik by Mozart, performed as part of the project, inspired me to conduct a case study on the Divertimento Sextet to investigate whether the double bass was indeed the standard bass instrument in this ensemble.

In order to arrive at a conclusive understanding, the study of the title pages and bass parts of the divertimento manuscripts proved indispensable. During the 18th century in Austria, the double bass was referred to either as contrabasso or violone. If one of these terms appeared in a manuscript, it indicated that the intended instrument was a double bass. However, this was not always conclusive evidence. Generally, the lowest note of the double bass in 18th century Austria was either F1 or E1. In reviewing a number of manuscripts that use the term violone on the title page and/or in the bass part, it became evident that the notes in the bass part extended lower than the instrument's playing range. This occurred in almost all instances on the weak beat of a cadence. In some divertimento manuscripts, only the term basso was used on the title page and the bass part. In these cases, the notes did not go beyond the lower range of the double bass. Nevertheless, this is not conclusive evidence that the piece was written specifically for the double bass, as the key of the piece may have influenced the range of the part. Additionally, some bass parts were titled in manuscripts as ‘Violoncello ò Violone’, implying that either instrument could be used. After examining several manuscripts of one particular divertimento, I discovered that the bass parts were labeled with different instrument names, such as violone, violoncello, and basso. This observation led me to speculate that the decision regarding the instrument name for the bass part may have been at the discretion of the copyist or determined by the availability of instruments in a particular location, whether it be for example, a certain city, noble court, or monastery.

The period between 1750 and 1780 marked a significant transition in the realm of music, as it witnessed the shift from the baroque to the classical era. During this time, there was a great deal of variation in the nomenclature and interchangeability of titles for instrumental music. Similarly, divertimentos, which were an important form of instrumental music during this period, also saw a great deal of interchangeability in the use of bass instruments. Various factors could influence which instrument was used in a performance, such as whether it was performed indoors or outdoors, or even the availability of a musician on a particular day. In contemporary jazz, to compare another genre, the choice of instruments in the rhythm section is purely optional. In some types of divertimento repertoire, such as entertainment music, the term basso could also have been used in the same way. After analysis of the manuscripts from the period, it became clear that there was no conclusive evidence to suggest that the double bass was the sole bass instrument used in the Divertimento Sextet. Nevertheless, taking into account factors such as the geographical location (which city, noble court, or monastery), the occasion of the performance, the performance venue (whether indoors or outdoors), and the availability of a particular musician could provide useful insights into determining which instrument, the double bass or the cello, was more likely to have been used in a given performance of a Divertimento Sextet.

List of Figures

Fig. 1 Title Page W.A. Mozart Musikalischer Spaß, Vienna: André 1797 http://mozartsmusicoffriends.com/title-page-of-w-a-mozart-musikalischer-spas/ (accessed January 6, 2023)

Fig. 2 Title page, ‘12 Divertimenti per camera’, Pietro Giuseppe Gaetano Boni (1720) By permission Dimitri Tassos

Fig. 3 Title page Divertimento a Violino e Basso, J. C. Mann, A-Wgm Vienna, Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien, Bibliothek (A-Wgm)