Art galleries and museums have traditionally fostered an atmosphere of quiet contemplation for the individual art viewer, guided in their appreciation by authoritative scholarship (Cuno 2006). Over recent decades, however, this approach to displaying art has been challenged, with increasing calls for museums to become more participatory, representative and open to alternative voices (McClellan 2008: 42–45). Eilean Hooper-Greenhill describes this process as a shift away from the ‘modern museum’ (a place where information is transmitted from museum to visitor) towards the ‘post-museum’ which she describes as a ‘process’ where interaction takes place through ‘partnerships’, ‘community groups’, ‘discussions’, and more (2000: 152). Stephen Greenblatt uses the terms ‘wonder’ and ‘resonance’ to describe these two different views, arguing that they are not mutually exclusive, and that visitors often benefit from a combination of the two (1991: 53–54).

So how can art museums create a space that facilitates a quiet, contemplative viewing experience, accompanied by high quality museum labels, while promoting inclusivity and diversity, and enabling active participation?

Ekphrastic Inquiry provides one possible solution to this problem.[1] Ekphrasis is most commonly defined as a description (Oxford English Dictionary online), representation (Heffernan 2004: 3), or creative response (Loizeaux 2010: 17) to a work of art. The development of ekphrastic writing is closely linked with the development of the art museum (Heffernan 2004: 137–38), and museums regularly employ various forms of ekphrastic activity, from poet-in-residence projects to educational workshops and museum anthologies (Denham 2010: 7). My research extends this existing practice beyond the realm of established writers or facilitated workshops, opening up the process of Ekphrastic Inquiry as a form of social, collaborative interpretation that can be utilized and enjoyed by all museum visitors in their own time.

The term Ekphrastic Inquiry stems from Poetic Inquiry, a method of research that is becoming increasingly common within the social sciences (Prendergast 2009: xix-xxiii). Many social scientists view the writing of poetry as a valuable method of knowledge production, enabling researchers to externalize their thoughts (Webb and Lee Brien 2018: 194–95), producing a greater degree of self-awareness for the writer, as well as an increasing awareness of the experiences, attitudes and feelings of others (Brady 2009: xi–xvi). My research transfers this methodological approach from the sphere of academic research to the social setting of the art museum.

The first stage of Ekphrastic Inquiry involves working with a community group, inviting members of the group to write ekphrastic poems in response to works of art. Many museums employ freelance writers to deliver projects of this kind. By working with marginalized groups museums begin to address the lack of diversity, representation and inclusivity that prevents such groups from participating in cultural activities. Working with National Museum Wales has enabled me to collaborate with two groups that fit such criteria. Guided by the museum’s engagement strategy, I initially delivered writing workshops for a group of people living in Rhondda Cynon Taf, an area of high deprivation in the South Wales valleys, inviting them to submit poems for an online interactive exhibit. I am now working with a diverse group of individuals, inviting them to write poems for an interactive exhibit in the museum itself.

The poems produced by marginalized groups are sometimes displayed in museums for other visitors to read, but this is often where such projects end, with little scope for understanding how such work may affect the experience of other museum visitors. My research takes this concept further in two specific ways:

1) Disrupting the viewing process

The ekphrastic poems written by members of these groups are presented alongside works of art in the museum gallery, providing more than one poetic response to each artwork. Visitors therefore encounter a set of alternative creative interpretations that challenge and disrupt the normal hierarchy of knowledge. My research has examined how the display of multiple ekphrastic poems responding to one work of art may alter the viewer’s perception, not just of the artwork, but also of the viewing experience itself. Data collected through an online survey and in-depth interviews indicate that such displays can open up the possibilities inherent within a work of art, enabling viewers to see the art object as complex, multifaceted, and latent with possible meanings. The data also show that such poems act as an alternative form of knowledge, adding nuance to existing museum labels, and enabling visitors who lack confidence in their ability to engage with art to feel empowered to share and articulate their own response.

2) Inviting dialogue and interaction

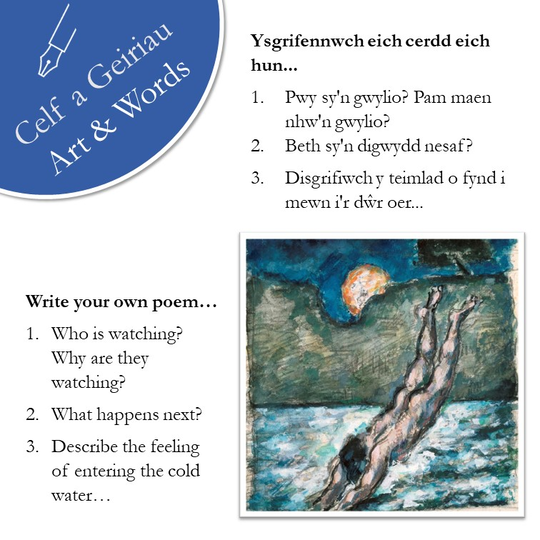

My research invites museum visitors to actively respond to such displays, encouraging them to write their own ekphrastic poem, with the option of adding it to the exhibit. Visitors may therefore respond, not only to the work of art, but also to the ekphrastic poems written by workshop participants, and to any other poems written by visitors. Opening out the process of Ekphrastic Inquiry beyond the prerogative of academic researchers or established writers therefore enacts an ongoing process of social engagement. It creates a democratic, dialogic community of creative response, as each poem interacts with and responds to those that came before. This process disrupts the normally invisible power dynamics at play in museum displays. It transfers agency from museum to visitor, while utilising and valuing the creative texts produced by marginalized individuals as a means of prompting such dialogue. This interpretive community of texts is both unified in its goal, and diverse in its multiplicity of perceptions.

As well as disrupting the viewing process, inviting dialogue and prompting interaction, Ekphrastic Inquiry enables the museum to complement their existing presentation of authoritative scholarship by facilitating two additional means of knowledge production. Visitors who spend time writing a poem, in a moment of private reflection, may experience a form of ‘embodied phenomenology’ as the writing process allows them to transform subconscious emotional or physical impressions into words (Reason 2012). As visitors read the poems on display, with the opportunity of contributing their own poem, they will experience ‘social phenomenology’, participating in a form of ongoing social, or communal, interpretation (Reason 2012).

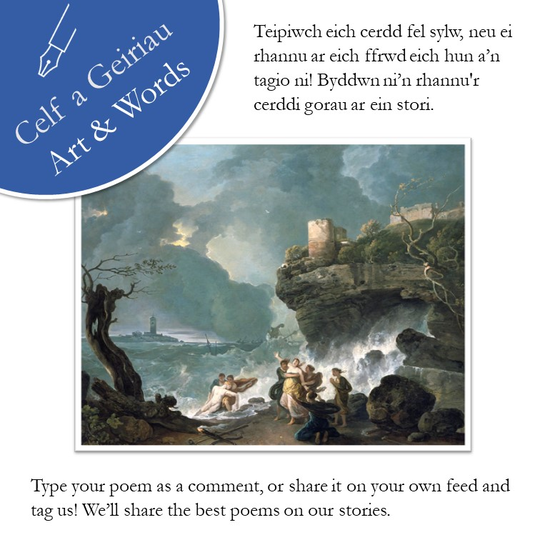

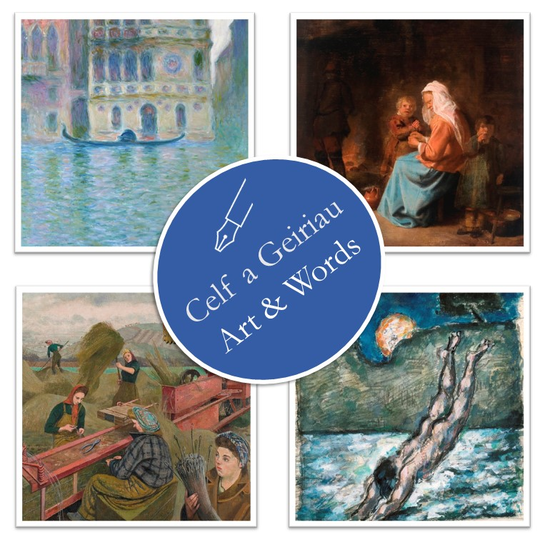

An online version of this research (developed in response to COVID-19 restrictions) is active on the National Museum Wales Instagram account, initially published between August and November 2021. A gallery-based version of this research will be available for visitor participation at National Museum Cardiff in the autumn of 2022.

[1] The term ‘Ekphrastic Inquiry’ was originally coined by Monica Prendergast (2006) to describe her ‘practice of writing poetry in response to audience and performance’. I am using this term in a different sense, specifically as a form of Poetic Inquiry. ↩︎