Performing the ecstasis: An interpretation of Katharine Norman’s Making Place for instrument/s and electronics

Jean Penny

Katharine Norman is a composer and writer of international repute. Her works for instruments and digital resources are inspired by people’s experience of place and landscape. Computer programming often forms an essential part of her creative work involving live audio and visual processing.

Making Place (2013) was commissioned by pianist Kate Halsall with support from the Arts Council of England and the Britten-Pears Foundation (score notes, Norman 2013).

Katharine Norman’s webpages can be accessed at http://www.novamara.com

All printed score and text examples are provided with permission of the composer.

Ecstasis — [ancient Greek — ‘ek’ (out), ‘stasis’ (stand)] — to stand outside or transcend (oneself) (https://www.britannica.com/topic/ecstasy-religion).

The ecstasis in this project is viewed as the state of flow achieved in performance, where the focus on the ‘doing’ is undisturbed, leading to a total involvement that can foster creative and intuitive responses.

Epoché — [ancient Greek—suspension of judgement] (https://www.britannica.com/topic/epoche)

Developed as a phenomenological process by Husserl, the epoché has been discussed in relation to understanding art (Merleau-Ponty 1968, 2009) literature, (Gosetti-Ferencei 2007), and performance of dance that incoporates technology (Kozel 2007). It has been rarely applied, however, to music performance. Crucial for this is the first-person stance taken, the bracketing of the experience (the phenomenon), and the reduction or description and reflective consciousness that follows. An example can be seen at https://www.musicandpractice.org/postcards-from-lockdown-translating-visual-art-to-music-for-flute-and-electronics-2/ (Penny 2021).

The epoché in this project situates the performance as a bracketed event. It is the space where the ecstasis can materialize and lead to subsequent reflections and conclusions.

Aims

1. To share artistic processes, responses and performative information through performance and reflexive discourse

2. To discover new ways for self-expression through a composed work that incorporates co-creation

3. To see what positioning the performance as an epoché might reveal

Introduction

Katharine Norman’s work, Making Place for instrument/s with live electronics (2013/16), combines recorded sounds, images, text, live interactive processing, and instrumental music performance to create a unique experience of place. As the performer, I can choose a location, collect photographic images and field recordings, and interpret and re-create the semi-improvised score. The piece is structured around a poem (written by the composer) that describes thoughts and sensations occurring in a walk — a quotidian walk set in familiar surroundings. ‘Walking’, stated Andra McCartney, ‘generates embodied knowledge through encounters with the dynamics of place. We become more of ourselves with each movement. Likewise, as we leave our trace, our presence shapes where we walk’ (2018: para 2). The trace in this instance is amplified through re-shaping the walking events into the piece, interpreting, constructing, performing, listening, and watching in a different context and time. The spaces of the piece — the poem, the sounds, the images, and the playing — unfold through this imaginary walk, creating an experience in which past and present collide.

Initially, I was inspired to create an interpretation of Making Place for my instrument, the flute, set amongst sounds and images recorded in Malaysia. This was an adaptation imbued with memories of place and intercultural interactions which occurred while living there between 2011 and 2016. Later, I imagined another version using alto flute and artefacts from my local Australian region — a version that, in 2020, seemed to align with our global staticity, need for social distancing, and self-isolation. This situation (the COVID-19 pandemic) has inspired new expressions and navigations of creative and performative work and its dissemination; it has also encouraged a turning towards the inside, re-evaluations of intimacy, and a deeper awareness of the nearby. Personally, I have gained more self-awareness and a more diverse resourcefulness, and given myself permission to take new paths. I have felt free to define my own challenges and an increased confidence to take risks with musical creativity and writing. From within this awakening to new possibilities, I was inspired to create a more quotidian version of Making Place centred around a walking/cycling trail, originally a railway track, near my home in Victoria, Australia.

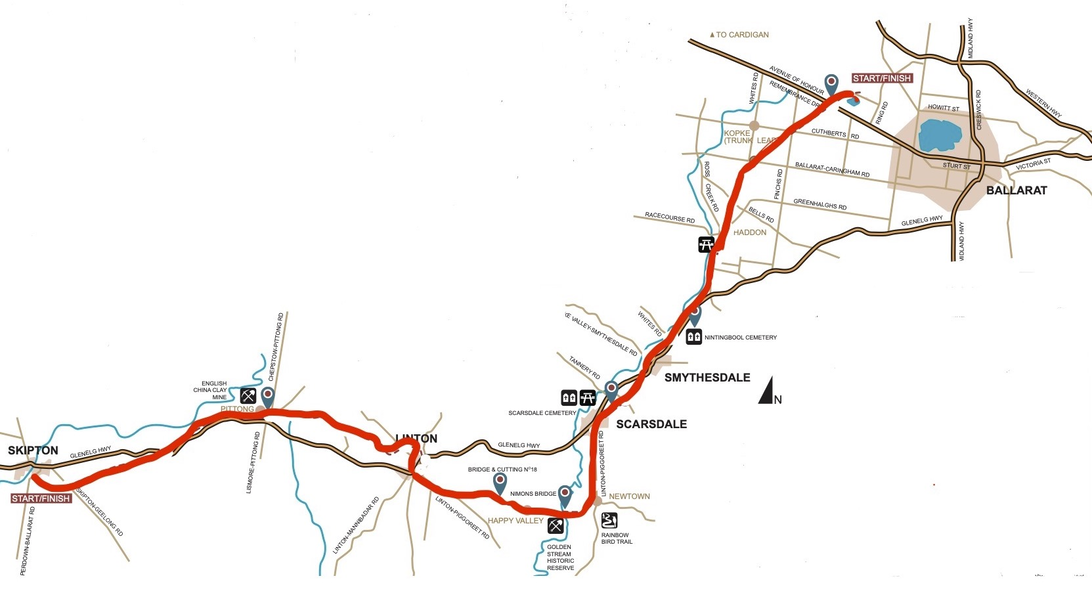

The Ballarat–Skipton rail trail covers 55 kilometres between the city of Ballarat and the small town of Skipton and includes twenty-four entry points at the sites of old stations (see more details here) The track passes through native grasslands, swamps, forests, towns, and farmland and crosses several historic trestle bridges. This was gold-rush territory in the nineteenth century: at each ‘stop’ or ‘station’ along the track a brief history is given, with emphasis on the gold mining, colonial developments of the area and the establishment of the railway (now defunct). Brief references to the earlier history of the First Nations people (Australian Aborigines) are found here and there — in particular the Wadawurrung and Dja Dja Wurrung people — whose connection with this area goes back tens of thousands of years (see more information here). This story is far more difficult to find and emerges as a muted underpinning, a murmuring that prompts contemplations of ancient societies and contemporary connections. Environmental sounds heard in this rural location are sporadic: frog calls, birds (kookaburras, magpies, parrots), our footsteps, the wind, the gate at the end of the trail, an occasional nearby car or dog bark, and the greetings of infrequent fellow-trekkers.

The quotidian, states Gosetti-Ferencei, is ‘the sense of life built up in daily experience, by everyday habits, by the sedimentation of ordinary expectations of the world, but also by the tensions between the regularity of the familiar and necessary innovation’ (2007: 1). Linking the ‘stepping out’ from this quotidian with the ecstasis, she posits that everydayness and phenomenological reflection create a possibility for transformation, for artistic creativity, that the ecstasis is ‘a source for revitalization of the everyday that opens new expressions of the feeling of life and new possibilities for its reconfiguration’ (ibid.: 11). In exploring the concept of quotidian through sound, image and text, Making Place prompts a shift in understanding, from a knowing about to a knowing from within, from playing and doing, to reflective awareness.

In this exposition I describe the processes of this exploration of place through the re-location, re-interpretation and performance of Making Place (flute version 2). To begin with, I share pre-performance thoughts — ideas of interpretation and the construction of method. I follow with an account of pre-performance activities — the walk, collecting materials, transcribing the music for alto flute, inserting new artefacts into the software, and rehearsals. Next come descriptions of the performance — necessarily occurring in isolation — and, finally, I offer reflective conclusions to the project.

Motivation, Aims, Method

Motivation for re-creating Making Place sprang from feelings arising from my first interpretation based in Malaysia: from the co-creation, personal connections, and memories evoked, and the sense of that place created in performance. Collecting field recordings and photos and constructing the improvisations and aesthetics of the piece had produced a unique experience, providing the impetus for a new version created from my current environment in Australia — to see how a re-interpretation would work, to see if it inspired new ways of thinking and playing, or offered new appreciations and connections. In addition to this artistic motivation, was the situation of COVID-19 restrictions.

In 2020, an existential change occurred with the COVID-19 pandemic; remoteness, intimacy, reappraisals of ‘home’ and relationships with environment become bound up with ideas of freedoms, new spatialities, and ideas of place. We began to think more about how we breathe, how we interact, how we invent new social constructs, and how we respond to the environment. In lockdown, we were advised to exercise in our local areas, triggering a new awareness and interest in available terrains and neighbourhoods. We constructed pathways through this new spatiality, as the presence or absence of humans precipitated a re-setting of physical and mental attentiveness, and a new intense listening. This new quotidian incited a search for meaningful artistic responses and a vast array of questions. In this project, competing strands of investigation emerged layer upon layer: geographic, historic, sonic, photographic, textual, performative. Also competing for attention were disrupting stories of the land, ancient history and colonization versus contemporary activism and simple enjoyment of space.

Making Place allowed me to find new artistic directions through engaging with my close surroundings, and potentially to invite an audience to share my immersion in this sphere. Additionally, improvisation had previously made up only a small part of my performance work: composed works were my main domain, from a grounding in classical solo, orchestral and chamber music repertoire to an early move to contemporary works for flute, and then flute with electronics. Setting out on this less frequented path would re-engage a sense of freedom and challenge my perceptions of performance identity and work. Linking the piece to my close environment with personally collected images and sounds also interested me, especially the potential to obtain a sense of shared ownership of the work through co-creation.

The main aims of this project were threefold: to share artistic processes, responses and performative information through performance and reflexive discourse; to discover new ways for self-expression through a composed work that incorporates co-creation; and to see what positioning the performance as an epoché might reveal. From the aims came considerations of method, the choosing of strands to observe, and ways of describing the experience. A multi-layered methodology evolved that encompassed practice, discussion, description and reflection. Phenomenological questions concerning images, recorded sounds, text, live flute sound and electronically generated interactivity evolved cumulatively. The performance itself was situated as an epoché, an event that emerged from pre-performance thinking and activities, yet was separated as an in-the-moment (temporal) space. Reflective discourse then looked back at this performance to discern meaning. This was essentially an experiment, a new approach to the performance as event (which may or may not fulfil expectations). The investigation juxtaposed voices of the flautist/researcher (myself) that recount process and describe and reflect on performance as lived experience. Through this I aimed to highlight the inhabited space of the piece by ‘doing’, and to activate and reveal awareness and insights gained from this work, Making Place, flute version 2. This methodology was always in motion, with merged processes of playing and writing, listening and rehearsing in tandem with constructing this exposition, performing (recording) the work, and responding in words.

Next page | Materials, Interpretations, Rehearsal Processes