References

[1] Conway, J, Kosemen, C M, Naish, D and Hartman, S. 2013. All Yesterdays: Unique and speculative views of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals. Irregular Books.

[2] Grabes, Herbert. 2008. Making Strange: Beauty, Sublimity, and the (Post) Modern ‘Third Aesthetic’. Vol. 42. Rodopi.

[3] Stern, Radu and Nancy J. Troy. 2005. Against Fashion: Clothing as Art, 1850-1930.

[4] Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso. 1921. ‘The Manifesto of Tactilism.’ Tactilism, Retrieved 29 October, 2016.

[5] Svankmajer, Jan. 2014. Touching and Imagining: An Introduction to Tactile Art. Bloomsbury Publishing.

[6] Rheinberger, Hans-Jorg. 1997. Toward a History of Epistemic Things: Synthesizing Proteins in the Test Tube.

[7] Borgdorff, H in: Schwab, Michael, ed. 2015. Experimental Systems. Future Knowledge in Artistic Research. Adapted edition. Leuven (Belgium): Leuven University Press, 112-120.

[8] Gadamer, H G. 2013. Truth and Method. A&C Black.

[9] Malpas, J. 2003. Hans-Georg Gadamer.

[10] Massumi, B. 1992. A User's Guide to Capitalism and Schizophrenia: Deviations from Deleuze and Guattari. MIT Press.

[11] Lester, S. 2013. ‘Playing in a Deleuzian Playground’. In The Philosophy of Play. Routledge, 130-140.

[12] Belk, R. W. 1988. ‘Possessions and the Extended Self’. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2): 139-168.

[13] Stasiulyte, V. 2020. Wearing Sound: Foundations of Sonic Design (Doctoral dissertation, Högskolan i Borås).

[14] Larssen, A T, Robertson, T J and Edwards, J. 2007. ‘Experiential Bodily Knowing as a Design (Sens)-ability in Interaction Design’. In European Workshop on Design and Semantics of Form and Movement. Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV.

[15] Wilde, D, Vallgårda, A and Tomico, O. 2017. ‘Embodied Design Ideation Methods: Analysing the power of estrangement’. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, May: 5158-5170.

[16] Fischer-Lichte, E. 2008. The Transformative Power of Performance: A New Aesthetic. London: Routledge.

[17] Harman, G. 2018. Object-oriented Ontology: A new theory of everything. Penguin UK.

[18] Varela, F J, Thompson, E and Rosch, E. 2016. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive science and human experience (revised edition). Cambridge, Massachusetts.

[19] Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

[20] Brett, Guy. 2004. Carnival of Perception: Selected Writings on Art.

[21] Ihde, Don. 2007. Listening and Voice: Phenomenologies of Sound. 2nd ed. Albany: State University of New York Press.

[22] Oliveros, P., 2005. Deep Listening: A composer's sound practice. iUniverse.

[23] Nancy, J L. 2007. Listening.

[24] Stasiulytė, V. 2022. ‘Listening to Clothing: From sonic fashion archive to sonic fashion library’. The Senses and Society, 17(2): 228-238.

[25] Dewey, J. [1934] 2005. Art as Experience.

[26] Maciunas, G and B Mats. 1981. George F. Maciunas. Kalejdoskop.

[27] Higgins, Hannah. 2002. Fluxus Experience. University of California Press.

[28] Cantz, F E W H, Leipzig, L. van B.-G. and Eterna, F. K. 1968. Franz Erhard Walther.

[29] Fink, Luisa. 1795. Franz Erhard Walther by Luisa Fink. Hatje Cantz.

[30] Bann, Stephen. 1995. ‘The Cabinet of Curiosity as a Model of Visual Display. A Note on the Genealogy of the Contemporary Art Museum.’ Définitions de la culture visuelle.

[31] White, Michele. 1997. ‘Cabinet of Curiosity: Finding the Viewer in a Virtual Museum.’ Convergence, 3(3): 29-71.

[32] Amsel-Arieli, Melody. 2012. ‘Cabinets of Curiosity (Wunderkammers).’ History Magazine, 13: 40-42.

[33] Mak, Bonnie and Julia Pollack. 2013. ‘The Performance and Practice of Research in a Cabinet of Curiosity: The Library’s Dead Time.’ Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America, 32(2): 202-21.

[34] Stern, Radu and Nancy J Troy. 2005. ‘Against Fashion: Clothing as Art, 1850-1930.’

[35] Schulze, H. 2019. Sound Works: A cultural theory of sound design. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

[36] Chion, M. 2015. Sound: An acoulogical treatise. Duke University Press.

[37] Holmstedt, J. 2017. Are You Ready for a Wet Live-in?: Explorations Into Listening. Umeå University.

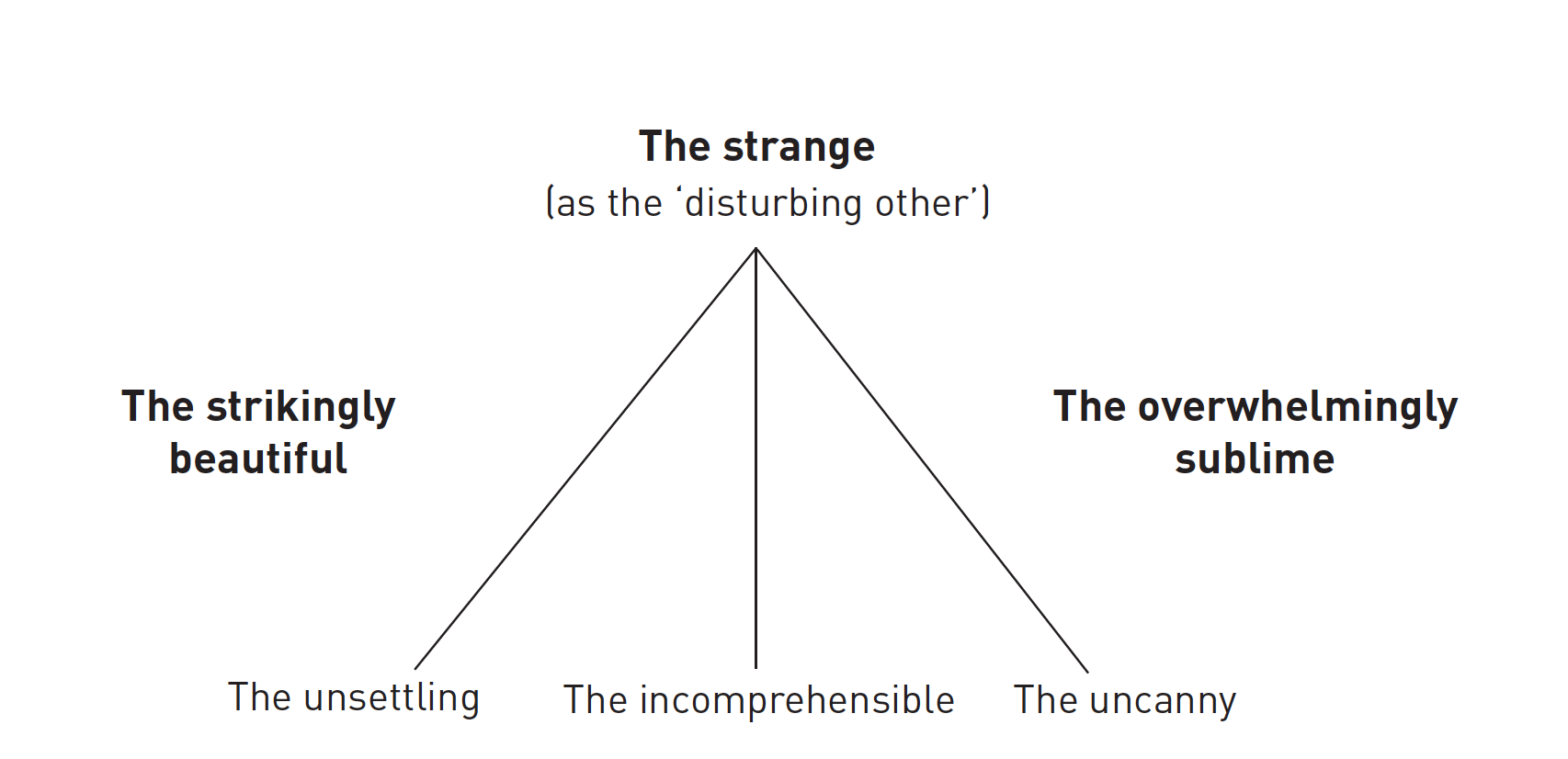

Aesthetics of the Strange

Fashion is primarily a visual ontology consisting of definitions, theories, and methods that are based on visual language. This artistic exposition revises fashion by approaching it from a different – sonic – perspective, where sound is considered a potential source for a new theory and a facilitator of the evolution of new methods rather than as a negative aspect. Sound is thus presented as the main idea-generator and not as a secondary quality of designed objects. It opens new avenues for design thinking with the ears rather than the eyes. An investigation of sonic expressions is seen as a disruptive fashion practice and could be described as a process of ‘unlearning’ that encourages the leaving behind of pre-existing knowledge about fashion expressions by shifting focus in the definition and design processes. Here, unlearning is seen as a practice of exploring and experiencing the relations in non-ordinary way, revising and thinking critically about what the preconceptions about these relationships are and could be. In the artistic book All Yesterdays: Unique and speculative views of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals [1] for example, the authors present ‘known unknowns’ of dinosaurs and speculate on ‘unknown unknowns’, offering visual sketches of these extinct animals that we have never considered before, proposing hypothetical identities, new appearances and new characteristics. Similarly, within this exposition, you are invited to explore a dressed body as a radical strangeness: non-visual and sonic.

The aesthetics of research artefacts in the collection Sound to Wear are not concerned with visual appearance, and instead focus on sound-based expression. The ‘unexpected or not yet unencountered’ [2]; the aesthetics of fashion expression exemplified by, e.g., anti-fashion [3] and ‘strangeness’ [2] are inspiration for ‘forgetting’ the ‘beautiful’; the main focus, then, is on sonic thinking and the sonic dimensions of object-subject relationships. As Grabes (2008) argues, the ‘third aesthetic’ [2] relates to disturbing and alienating experiences, which are highlighted by the expression of the artefact. This third aesthetic [2] is located ‘between the traditional ones of the beautiful and the sublime’ [2]. Attempts to create ‘as great a sense of strangeness as possible and shifts in expressions are achieved through the constant presentation of “the new”’ [2]. According to Grabes (2008), cubism, surrealism, and dadaism arguably involve radical strangeness and constitute shifts in thinking and expression. Proposals for different ways of thinking can be seen in the manifestos of artists engaged in tactilism [4, 5], which introduced a different method of expression. The third aesthetic [2] is a ‘generator of surprises’ [6] and involves presenting alternative realities in unusual ways. In artistic research, artworks are epistemic things and events that have not yet been ‘understood’ or ‘known’ – or, certainly, that resist any such epistemological handle. Art’s knowledge potential lies partly in the tacit knowledge embodied within it and partly in its ability to continuously open new perspectives and unfold new realities [7]. Thus, the concept of third aesthetic [2] is important as a discourse on unlearning fashion by exploring, designing, and presenting it in unexpected ways. An example is considering it from the sonic perspective whilst employing the method of play that encourages curiosity and experimentation.

The concept of ‘play’ (Spiel) has an important role in Gadamer’s work, [8]. As Malpas writes, Gadamer takes play as the fundamental evidence of the ontological structure of art, emphasizing that play is not a form of disengaged, disinterested exercise of subjectivity, but instead has its own order and structure [9]. The structure of play has obvious affinities with all of the other relevant concepts here – of dialogue, phronesis, the hermeneutical situation, the truth of art. Indeed, one may view all of these ideas as slightly different elaborations on what is essentially the same basic conception of understanding: one that takes our finitude, that is, our prior involvement and partiality, as an enabling condition for understanding and not as a barrier to the same [9]. Massumi [10] suggests that from this perspective, play is a reminder us that the future is not given, but always contains the potential for novelty and the unexpected. It asks ‘what if’ the world is thought, felt and acted on differently, and in this prompts different becomings, new trajectories, new responses, and unheard-of futures [11].

SOUND TO WEAR: The Cabinet of Sonic Curiosities

A collection of thought- and body-provoking playthings for sounding and listening practices

Vidmina Stasiulytė, PhD in Artistic Research, Fashion Design

Sonorous Dressed Body

Identity in fashion is visually dominated. Nonetheless, sound adds another layer and may be considered part of the construct of the self. If you close your eyes, you can hear people talking, breathing, walking, etc. Fashion also comes into play: the jingling of metal bracelets is audible as an arm moves, as are the zipping or unzipping of a synthetic sports jacket, the electrostatic rasp of someone taking off a knitted sweater in winter, the click-clack of high heels, the squeaking of sneakers. Individuals are even identifiable aurally due to their gait. As sonic objects that we ‘wear’ everyday, mobile phones add various sounds to our sonic identity, e.g. those of communication tools (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, etc.), each of which utilizes a unique notification sound for a new message, an incoming call, disconnection, etc. Here, the mobile phone becomes a ‘parlor organ’ [12], an extension of the sonic self. [13]

The research topic was defined by identifying the boundaries of fashion, and it explored alternatives to visual fashion discourse. Rethinking aesthetics and shifting from the visual to the sonic dimension opened up for a new and unexpected concept: sonic expression. This suggests new ways of approaching fashion practice through the exploration of an artistic research methodology at the intersection of fashion, art, and philosophy, seeking to extend the potential of alternative fashion expressions [13]. The ambition here is to unlearn what we knew about fashion in order to learn something new about it. I ask the question: is it possible to unlearn habitual and dominant modes of thinking/doing by turning to an auditory domain? What methods are suggested if we consider sonic expressions as an alternative state of an item of dress/wearable object?

The exploration of sonic expression became a four-year experiment and resulted in a doctoral thesis [13]. Sound to Wear is a part of this research, and it is presented in this exposition as an otherness, or potential for thinking in the field of fashion and merging disciplines. It is an introduction of alternative methods and art practice for a field as visual as fashion; it aims to open up the field and render it more experimental, critical and inclusive. It could be seen as a practice of empathy, as it considers e.g. individuals who experience their surroundings by other senses than sight.

Methodology

Using the design variables as a conceptual background, a series of design experiments were made with sound objects and presented as audio-visual sketches. The basic motivation for the experiments was twofold: (i) to use conceptual design as a driving force in investigations of the expressiveness of sound in relation to timing and spacing, and (ii) to use the experiments as a basis for design thinking. The methodological issues addressed in the research were:

• considering a type of dress/object with respect to expressions of wearing;

• focusing on the body meeting material – an aspect of body parts in action;

• focusing on the full body in action when wearing a particular sonic ‘dress’ as a single/complex element, single/complex composition, and complex system.

Methodological issues were investigated by considering different categories of sonic material such as rhythm, tempo, volume, and the variability of sound in space and time. In addition, the investigation included extending the body through sound in various directions and manners, including with sonic points and sonic clusters [13]. By exploring different sonic expressions of the same movement, e.g. by filling the same object with different materials (water, sand, ping-pong balls, etc.), it was possible to engage with forms of expression in connection with physical acts such as lifting and bending an arm. This analysis also provided an understanding of the relationship between the construction and sonic expression of a ‘dress’. The shift from everyday actions such as wearing (or walking, sitting, typing, etc.) to unusual movements such as performing sound provided new insights into how to design temporal expressions.

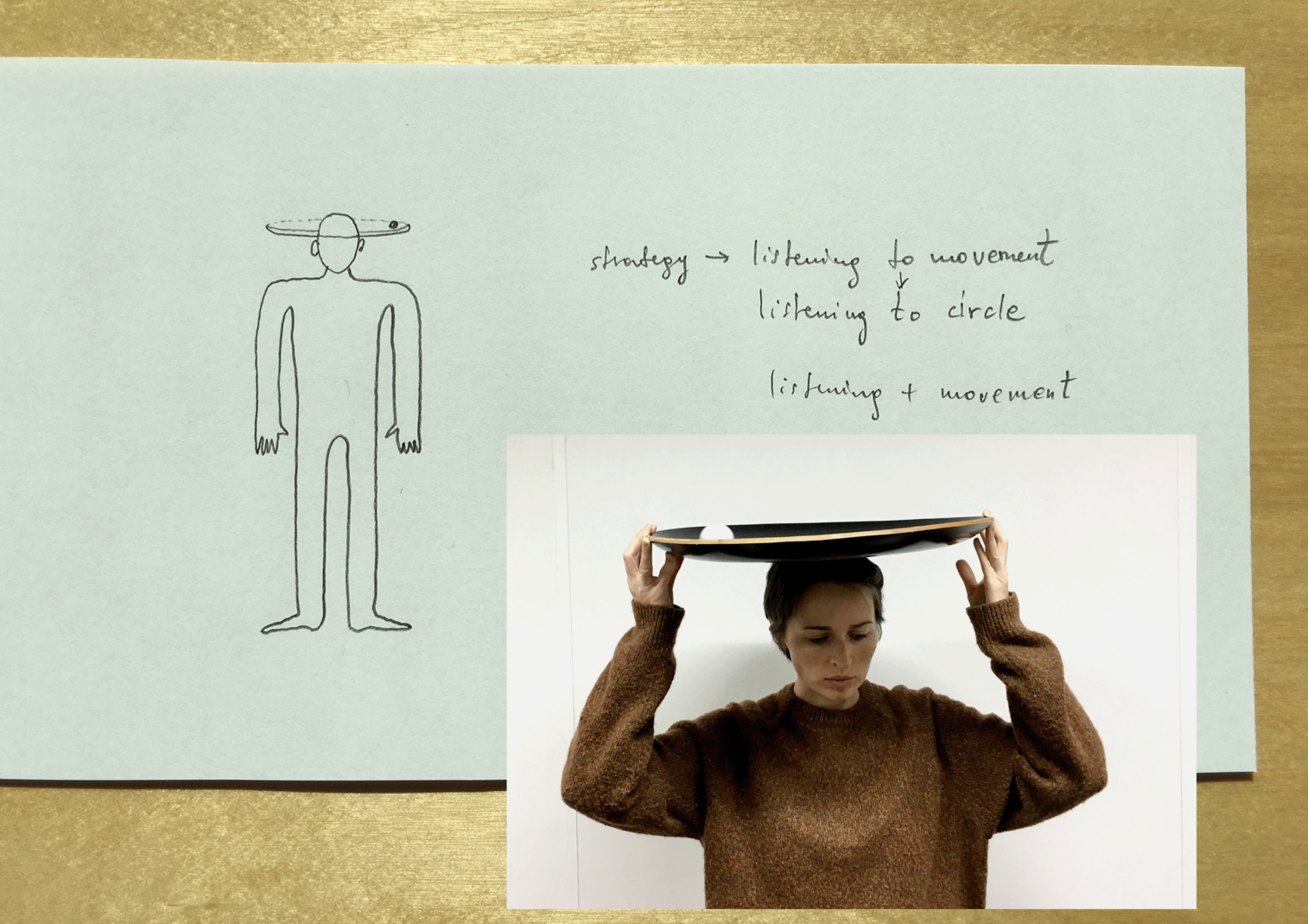

Knowledge of sonic expressions was gathered by exploring bodily experiences and using the ideation method [14] within listening and sounding practices. Sound was investigated with gradually increasing complexity, from a single/complex element to a dressed body. By sound-thinking whilst undertaking the short, simple audiovisual sketches, I tried to free myself from common preconceptions and imagine new interpretations of garments and new body-dress movements and interactions for expressing sound. This process resulted in tools and methods for designing sonic expressions.

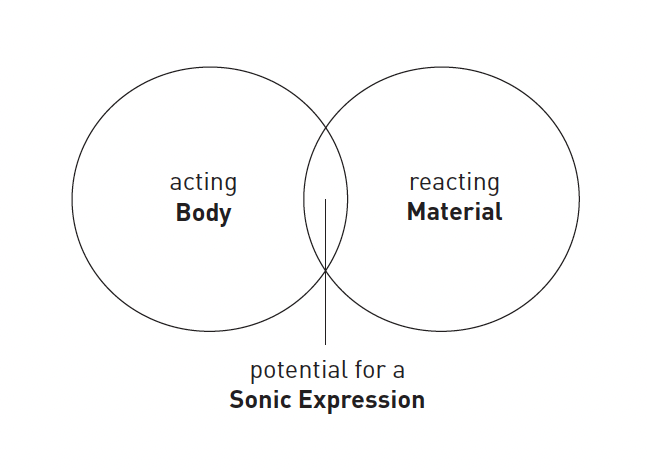

The potential source of a sonic expression: the 'meeting point' of an acting body and reacting material

The embodied sound ideation is oriented towards a rudimentary playful exercise in sensorial exploration and relational

body-object possibilities.

‘[O]bjects are like instruments for something. The objects themselves are not important, but what one does with them, what becomes possible with and through them is.’[28]

Body-Object: Relations and Interactions/Intra-actions

A discourse on sonic matter and audio dimensions seeks to expand the everyday ontology of body-object relations. A relation defines a sound, and sound is wholly a matter of relations: where a sound-object is placed on the body, which body movement activates the sound, etc. The expressive/mediating body-object relations centres on sound-based thinking. This sound-based thinking is carried out within the kinetic-haptic-sonic interaction, and sound is embodied in the act and enacted within the body through the expressive object – an item of dress/wearable object. It is an evocative phenomenon, object-stimulator, and idea-generator. The process of thinking and designing with sound involves somatic experience and complex kinetic-tactile-sonic interactions: a sonic expression is enfolded in time and space within the act. However, space is more central for this performative relational act; the acts in question are non-compositional, rather intuitive sounding-listening or listening-sounding acts. Time here is important as a slow-down/being-in-a-moment practice. Sound is shaped by the space and the body-object kinetic-haptic interactions that result in sound.

These relations are similar to the concept of an ‘autopoietic feedback loop’ [16] introduced by Erika Fischer-Lichte, which refers to the relationship between performer and audience during a performance. Attending a performance event requires spectators to interact with a performative space, the performer(s), the content, and the spatial design of the work. For this exposition, the audience is invited to interact with sound tools for co-sounding/co-listening practices that are active, reflecting/feedbacking the heard sound back to this communal sonic happening; these multiple beings and becomings coexist in the same space [17]. Sonic immersion becomes a participatory and collaborative act through embodied cognition/embodied mind [18]. The object, in this case the sound tool, is as important as the human body; it is an invitation to explore what an object might say to the body, similarly to Object-Oriented Ontology, ‘with a rejection of anthropocentric ways of thinking about and acting in the world’ [17]. A sound tool is not merely a material object, but also an event, performance, the thinking act and a place for relations, new meanings, and the practice of cognitive thinking. Some examples are the work of Hello Oiticica, Lygia Klark, Franz Erhard Walther, and Rebecca Horn. Sound tools emerge through the intra-actions as proposed in Barad’s theory of agential realism, where agency is defined as a relationship and not as something that one ‘has’. [19]

Ontological Thinking and Sensorial Experiencing Through Objects

In contrast to visual experience and image thinking, aural experience and sound thinking change the fundamental manifestation and perception of a dressed body from being looked at and seen to being listened to and heard. Looking at a body wearing high heels is a fundamentally different experience than and listening to a body wearing high heels [13]. Thus, from an auditory perspective, the dressed body is understood as a dynamic, temporal form, rather than a static one, as it is in visual representation (e.g. in a photograph). The visual unfolds inescapably before our eyes, whereas sound surrounds us. Whilst seeing is static and the experience is immediate, hearing unfolds over time: it is ‘a progressive integration of the object in the experience of the subject’ [20]. Shifting focus from visual to audial thus entails a reorientation in terms of design thinking and design modes to be based primarily on sound. A shift to the auditory dimension is thus potentially very difficult. It begins as a deliberate decentring of a dominant tradition in order to discover what may be missing as a result of vision – traditionally the main variable and metaphor – being reduced.

The examination of sound begins with phenomenology. This style of thinking directs an intense examination of experience in its multifaceted, complex, and essential forms [21]. What is phenomenological listening? More than intense and concentrated attention to sound and listening, it is also an awareness throughout the process of the pervasiveness of certain ‘beliefs’ that intrude on our attempt to listen ‘to the things themselves’ [21]. It is listening to differences in auditory texture, shapes and durational becomings – sound unfoldings. It is a being in presence lived through time in space. It is a polyphony of experience, a simultaneous outward and inward listening. It is a self-directed activity, a performativity of multisensory expressions and different modes of wearing sound. Here, listening practice follows the concept of ‘Deep Listening’ [22]. Deep Listening entails going beyond the surface of what is heard, expanding to the whole field of sound while finding focus [22]. Listening reveals sound as a structure of resonance, an infinite sending and resending [23]. The sound tools, whether they are focused on listening or sounding practice, are constantly shifting: local-global and sending-receiving.

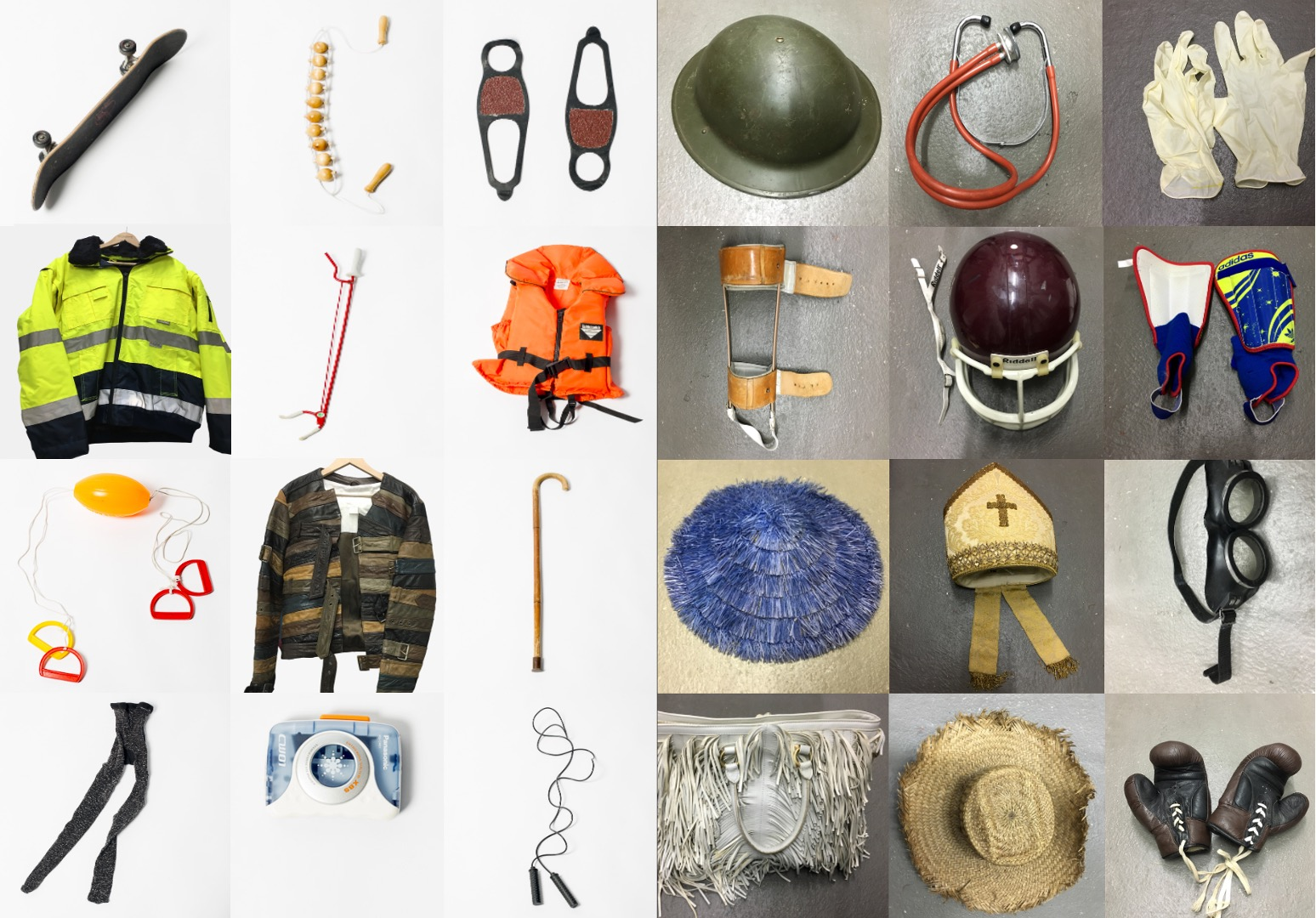

The practice begins with listening, as the shift to non-visual, temporal, sonic expression is challenging. This primary listening practice consists of listening to fashion items and is seen as ‘revision’ – it is listening to ‘dress’ by touching and wearing it [24]. This study took approximately two years, during which I collected and recorded the sounds of various fashion items in different museums (e.g. Textile Museum, Sweden), costume archives (Theaterkunst, Germany), second-hand shops, my own closet, etc. This listening practice resulted in the digital platform Sonic Fashion Library, which comprises 400 sounds. The practice led me to the need for tools and methods to re-focus and shift from the visual to the non-visual dimension.

This exposition presents the experimental toolkit Sound to Wear, which consists of 29 sound objects for sounding and listening practices. The toolkit is designed to explore sonic experiences and think through sound. In Art as Experience, Dewey writes that ‘[t]he senses are organs through which the live creature participates directly in the world about him’ [25]. The tactile tools Dewey used in his educational experiment at the Lab School in Chicago often involved containers holding objects to create a range of multisensory explorations, the function of which is strikingly similar to that of multisensory Fluxkits [26]. Fluxkits are comprised of collections of various objects that prompt the senses and bodily presence [26], such as Ay-O’s Finger Box Set (No. 26), which consists of 15 natural wooden ‘finger boxes’, each containing a different object to be explored through touch. An object is considered a sensorial filter [20]. Fluxus materials are useful in precisely such an emancipatory sense because they provide contexts for primary experiences. As Fluxkits are multisensory, they exemplify the modality of knowledge that Levin has called ‘ontological thinking’ [27]. Similarly, the toolkit Sound to Wear was designed for experiencing sound differently in regard to sonic textures, shapes, the associations it elicits, the meanings it produces, etc. The playful and experimental approach to this ontological exploration starts with the embodied sound ideation/embodied thinking practice presented in audio-visual sketches in this exposition.

Sonic expression unfolds in time through a haptic-kinetic body action.

‘What happens in the action constitutes the work.’[29]

‘Sometimes I want to avoid using my white cane as it has a negative association with regard to my blindness. Then I am wearing a polyester sport jacket and walking in the city;

it makes a lot of sounds so I can echolocate. Or I follow a person wearing high heels, and that person becomes my guide without knowing it!’[13]

From an interview with a research participant, June 2017, Vilnius, Lithuania.

Sound to Wear: Playthings for Listening and Sounding Practices

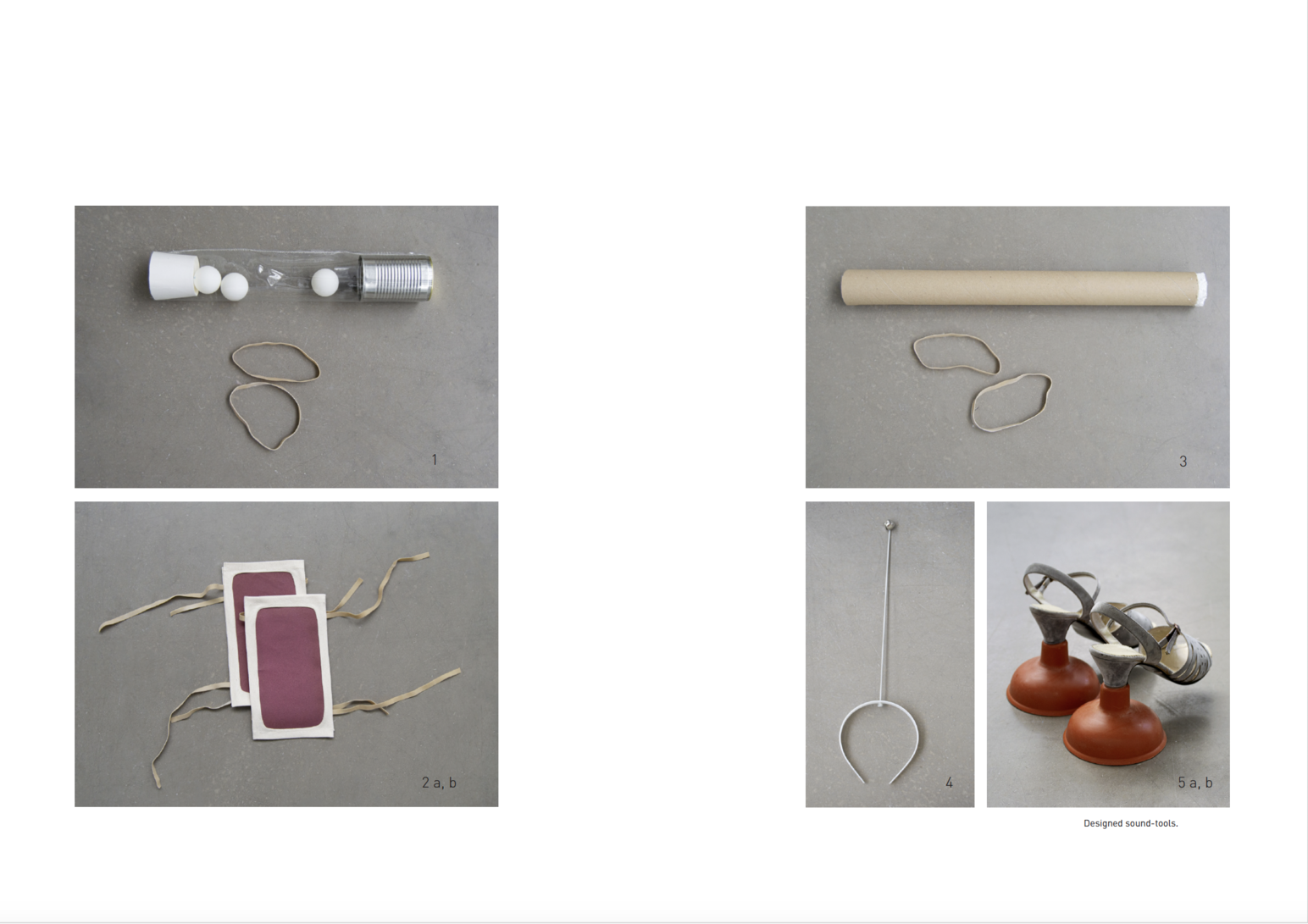

Play and openness to mistakes and surprises are crucial for originality in design practices. Gadamer [8] presents the concept of play in reference to the experience of art as meaning the mode of being of the artwork itself [9], rather than the orientation or even the state of mind of the creator or of those enjoying the work of art, or the freedom of a subjectivity engaged in play. The educational set of sound tools is one outcome of the doctoral research Wearing Sound: Foundations of Sonic Design [13]. The tools are body-based objects and could be considered ‘object-stimulators’: objects that generate ideas and inspire new relations. The tools are complex material-discursive apparatuses assembled from everyday objects and centred on two main practices: (i) listening and (ii) sounding. The set of tools is arranged into a sequence for working with sonic materials that begins with ‘ear cleaning’ – introducing, activating and shifting the focus from visual to sonic experience – and continues with idea-generation in relation to designing with sound.

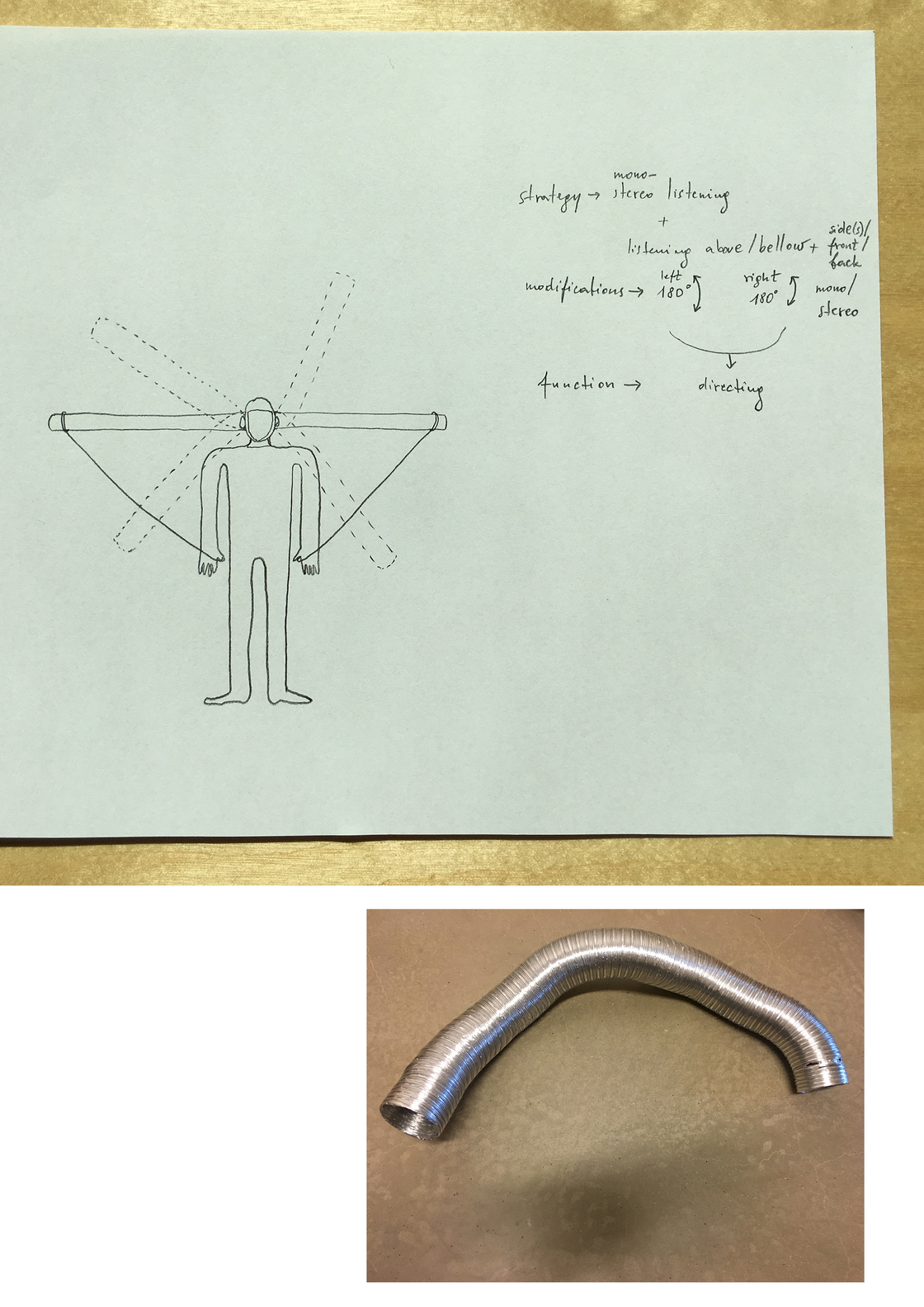

The sound tools for listening invite focus on and exploration of various listening modes. They work as stimulators that modify hearing in different ways by directing, blocking, amplifying, damping, reflecting or isolating. With some objects, one can direct the listening at different heights – for example, the half-metre listening shoes. Various directionalities could be investigated with the headphone tube; for example, one might listen behind, above, below, to the right or left, or listening to different directions at the same time. The acousmatic listening mode could be examined with the ‘dress-box’, which also damps the surrounding sounds. Some tools are designed to experience individual isolative listening, whilst other tools are dedicated to exploring co-listening modes.

The sound tools for sounding encourage the listener to delve into different aspects of sound related to e.g. the location on the body and specific movement/interaction for activating the sound. Some objects invite experience of mono, stereo or surround sound and more; different sonic expressions of material reacting to a body movement such as floating, bouncing, dragging, sliding, rattling, squeaking, etc. Some tools allow exploration of the semantics of sound, such as the object with metal sponges, reminiscent of the sound of walking on snow, whilst other tools, such as the plunger shoes, disrupt their signifier. The wearer is encouraged to experience the body extensions with sonic clusters and sonic points, everyday- and non-ordinary movements, different volumes and emotions that sound elicits, from the annoying, abrasive sound of sandpaper tights to the pleasant, sloshing sound of the ‘water-apron’ or the ambient meditative sonic expression of the sound tool made from 1000 rubber fingers. By wearing the ‘ball-anklet(s)’ or ‘double-cap’, one can explore asymmetrical sound. The sound tool with pumps functions as a sounding piece that invites experimentation with the amplified sonic expression of sitting. Sound tools could be mixed and worn together.

Each sound object was designed to enhance a particular movement or behaviour. The notion of sound tools is open, and the tools facilitate exploration; they are playthings similar to those exhibited in a cabinet of curiosity [30; 31; 32; 33], allowing designers to explore these tools in their own way or follow the provided instructions. This opens up an experiential and pedagogical space in which creativity and aesthetic engagement can be collectively and individually explored.

The sound tools were assembled from everyday objects (e.g., sink plungers, sandpaper, brushes, etc.). The ‘aesthetics of the strange’ [2] of objects are not concerned with visual appearance, but rather function, interaction, and emitted sound. Their importance relates to everyday performativity and simple/ready-made objects. As discussed in the section ‘Aesthetics of the Strange’, the third aesthetics introduced by Grabes [2] and anti-fashion [34] refer to ‘strange’ aesthetics and argue in favour of ‘forgetting’ what is visually ‘beautiful’. The main focus has thus been on sonic thinking and the sonic dimension of the object-subject relationship.

The listening objects modify hearing by amplifying, filtering, directing, damping, and isolating sound. The main methods for sounding objects are based on the ‘meeting point’ between the acting body and the sounding material, where the body’s movement suggests the expression of sound. The properties of sound, such as complexity, repetition, and volume, are thus the design elements for a sound to be expressed in different ways. Extending the body with ‘sonic points’ or ‘clusters’, composing the fabric or multiplying sonic elements, could suggest design ideas as well. Methods of listening and sounding are proposed within the designed sound tools; these build on the foundation for introducing and designing sonic expressions.

On the following page, ‘Play Sound’, the reader is invited to listen to objects-body-making-sounds and explore sonic possibilities. Feel very welcome to play just a single sound or make your own sonic composition by activating the sounds of several objects. Welcome to the Sonic Curiosities!

Sound tool 11

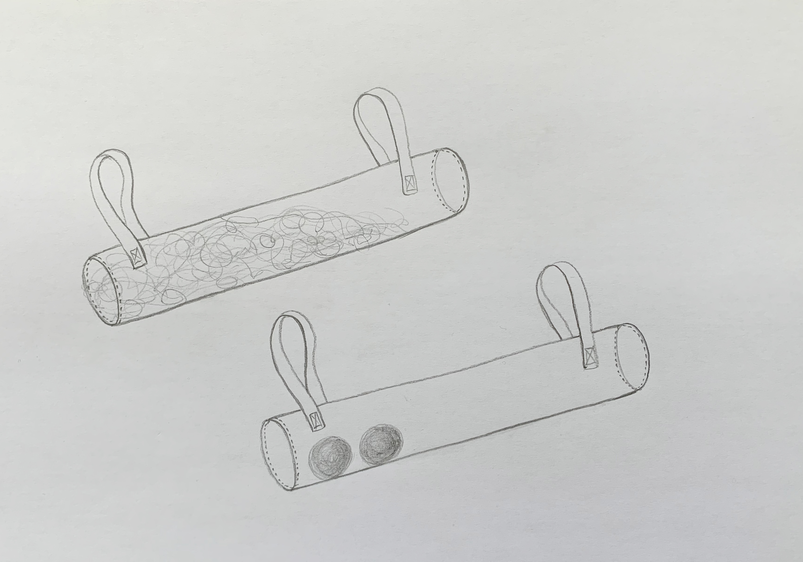

Sounding tool: PVC, rubber bands, three ping-pong balls, two metal cans

Sounding modes: asymmetrical amplification, sonic points, changing tempo

The object is intended to be worn on the arm or foot. It functions as an asymmetrical sounding piece. The sounding can be undertaken in different ways by lifting, shaking, or rotating the body part that it is being worn on at various speeds.

Sound tool 15

Sounding tool: wool, 1000 rubber ’fingers’, rubber bands

Sounding modes: symmetrical/asymmetrical amplification, cluster(s), changing tempo

The object should be worn on the side(s)/ leg(s). It functions as an asymmetrical or symmetrical sounding piece. Sound tool 28 consists of 1000 rubber ‘fingers’ and invites exploration of subtle, ambient sonic expressions when being worn. The sounding could be made in different ways by wearing the objects at various speeds – slow/medium/fast – which will result in different sonic expressions.

Sound tool 19

Sounding tool: PVC, water, cotton bands

Sounding modes: amplification, sonic cluster, changing tempo

The object should be worn on the waist. It functions as a sounding piece that invites exploration of a ‘floating’ expression of walking. The sounding could be made in different ways by wearing the ‘sonic-apron’ at various speeds – slow/medium/fast – which will result in different sonic expressions.

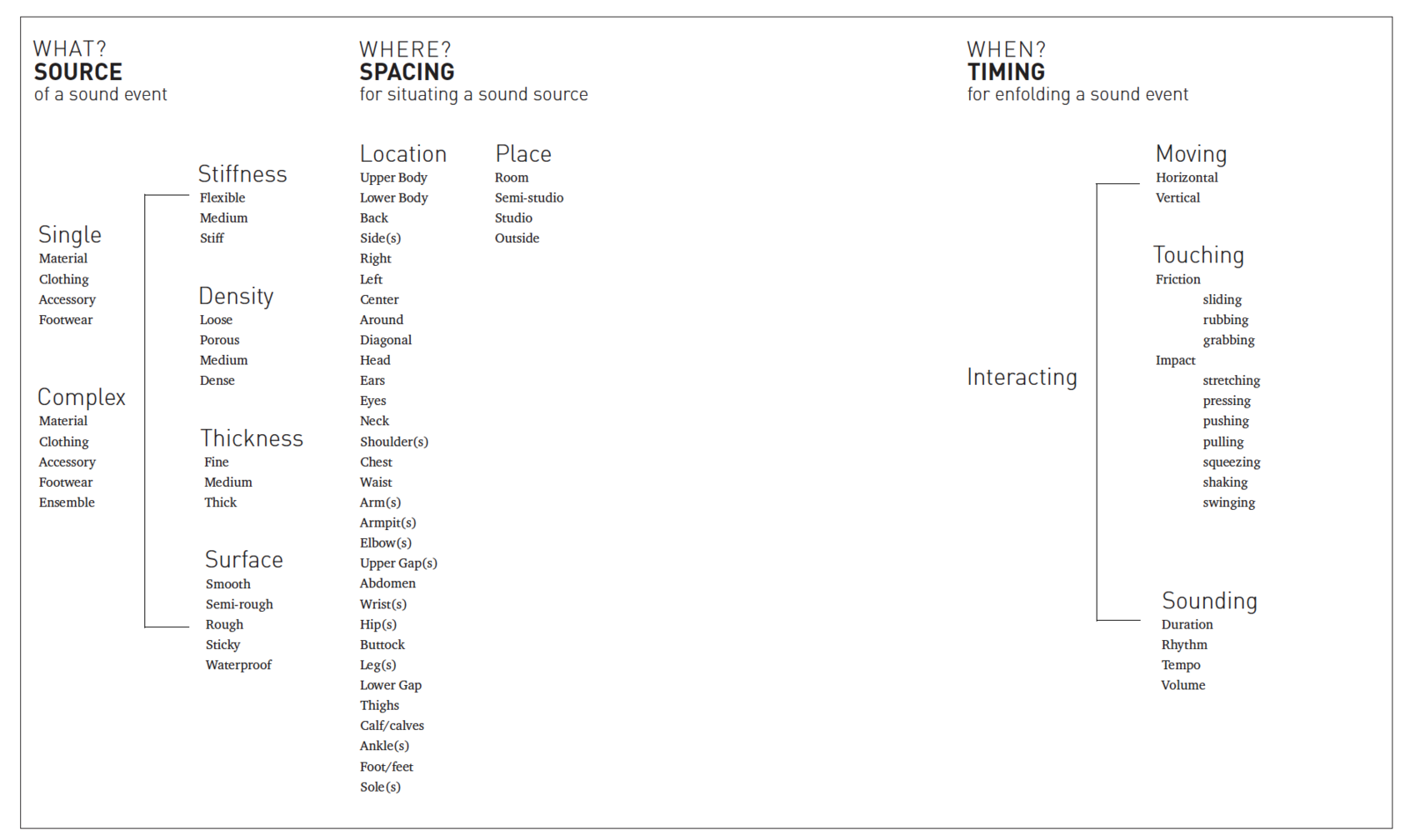

Development of Sonic Design Variables

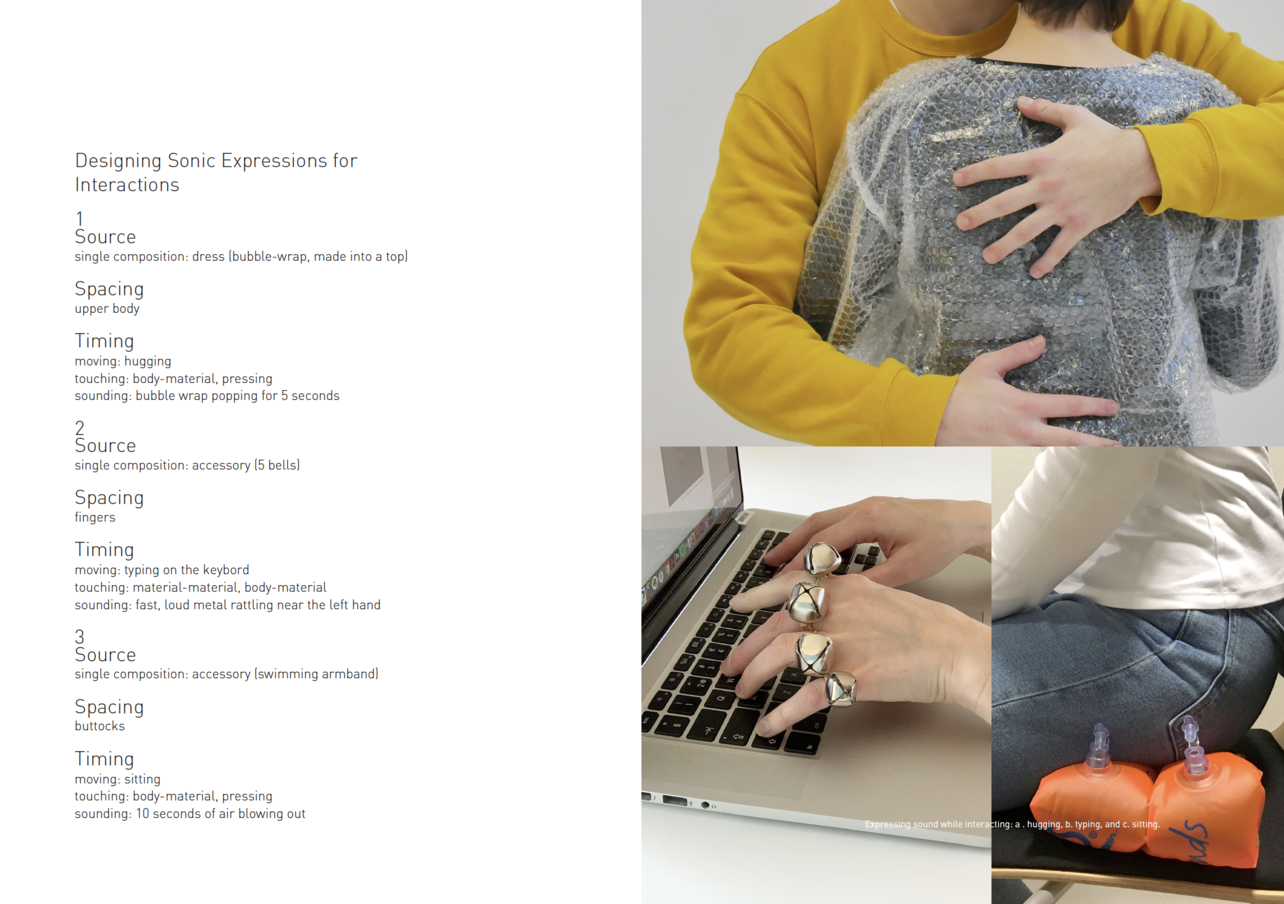

The core sound variables chosen centre on notions of tactility, space on and around the body, and kinaesthetic sensory experiences in relation to the dressed body. Sonic expression is dependent on three main categories:

(i) source,

(ii) spacing,

(iii) timing (see image above).

In the research presented here, sound sources emphasize the complexity of a sound event; spacing situates the sound source; timing enfolds the source of a sound in a sonic event. These sound categories can be seen as design variables with which to design different sonic expressions.

Sound Source. The source of a sound could be a single or complex event created by a body-dress interaction. The source of the sound of dress may be materials, clothing, accessories, footwear, or the combination of all of these to create an ensemble. A single sound source is defined by a single fabric, other material, or item of dress/wearable object that is made from the same material. A complex sound source is any material or item of dress/wearable object that is made from more than one material.

Locating Sound. The human body is never outside of a situation: an individual body is situated, and it is located. It is characterized by its temporal and environmental situation [35]. Although sound is ephemeral and spreads in all directions, the location of its source is often possible to identify. Sonic expression happens around an object, and the body is enveloped by the sound emitted by an object. Chion (2016) describes the sonorous envelope as both a no-place and the all-around: somewhere not yet localized or distinguished [36]. The sonorous envelope is thus at once fluid and enclosing. [37]

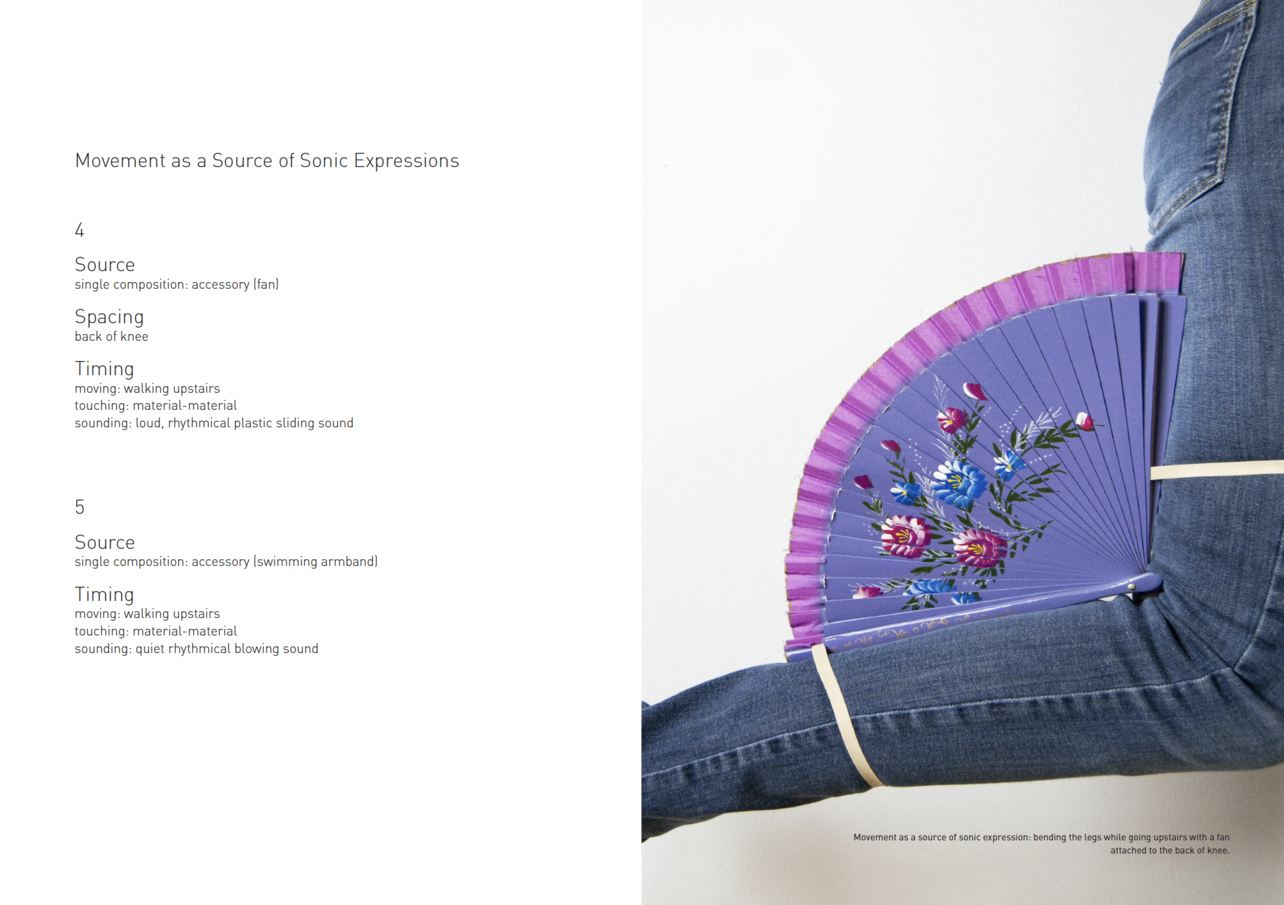

Duration. The duration of a sound is defined by the duration of tactile interaction. The category of timing defines the interaction itself. It is threefold: tactile, kinetic, and sonic, and all three are time-based acts. Movement can be divided into horizontal and vertical planes. Sound is generally emitted as a result of an interaction between the elements of a dressed body – arms and legs touching each other whilst sliding horizontally or vertically, for example, as when walking up stairs. Touching can be frictional and involve impact, while friction can vary, and involve sliding, rubbing, or grabbing. Impacts on materials can involve stretching, pressing, pushing, pulling, squeezing, shaking, or swinging. Sounding can be influenced by rhythm, tempo, and volume, as described by the loudest emitted sound – the true peak.

Sound tool 1

Sounding tool: wood, rubber band, metal, and baseball, tennis and ping-pong balls

Sounding modes: amplification, form-sounding, changing tempo

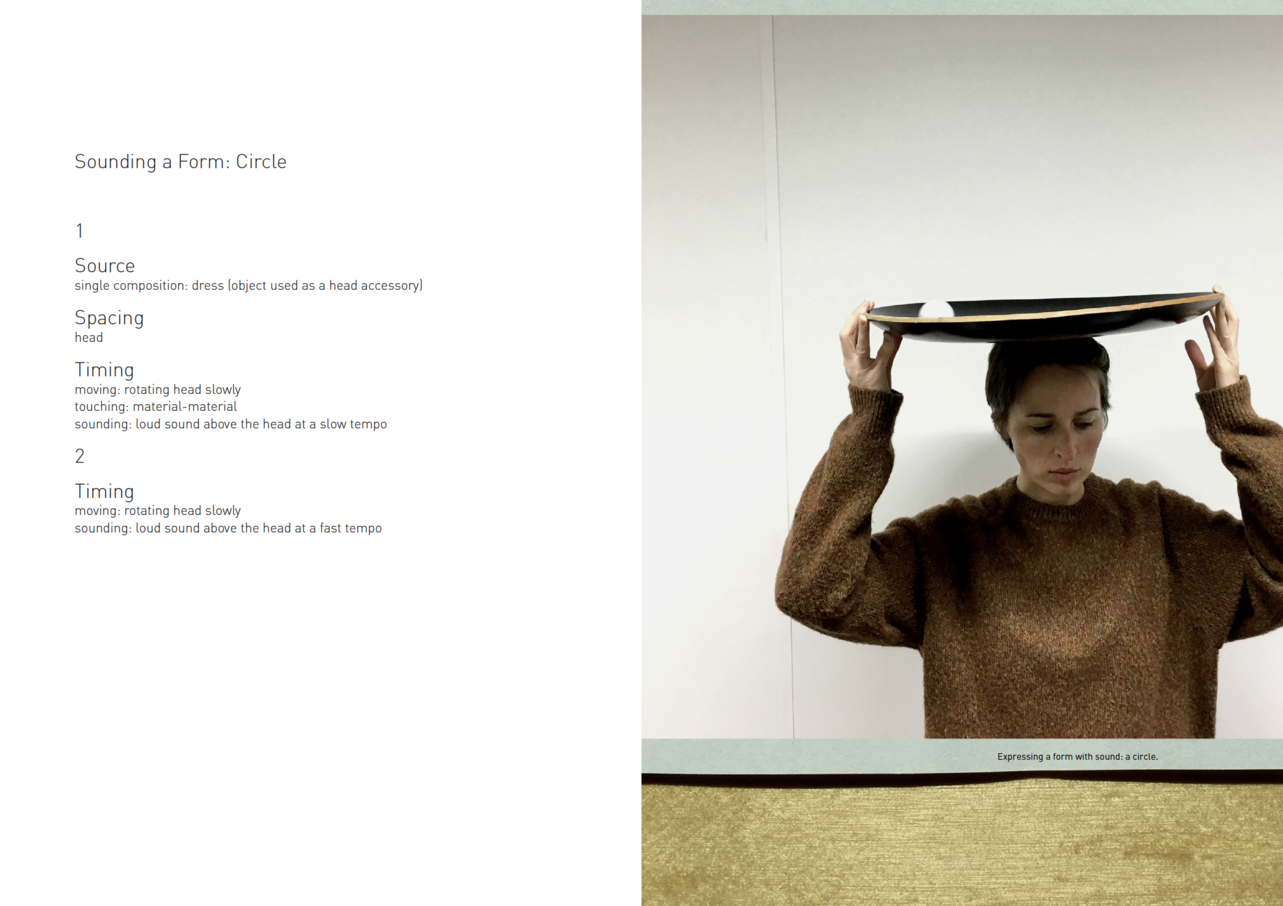

The object is intended to be worn on the head. It functions as a surround-sound piece. The sounding can be undertaken in different ways by rotating the head at a slow, medium, or fast pace with balls of different weights, resulting in sonic expressions with various volumes.

Sound tool 6

Sounding tool: tires, cotton and rubber bands

Sounding modes: symmetrical amplification

The object is intended to be worn on the thighs. It functions as a symmetrical sounding piece. Sound tool 6 demonstrates the amplified expression of walking.

Sound tool 16

Sounding tool: PVC, cotton and rubber bands, metal fastening, ping-pong and metal balls, metal can

Sounding modes: extension, amplification, sonic point

The object is intended to be worn on the waist as an extended sonic ‘tail’. The sounding can be undertaken in different ways by wearing three attachments that invite exploration of different material reactions while walking: the sound of dragging, bouncing, and rattling. A recommendation is to explore Sound tool 16 while walking and climbing stairs on various surfaces.

Sound tool 7

Sounding tool: boots, metal hairbrushes

Sounding modes: symmetrical, amplification

This object is intended to be worn on the feet. It functions as a symmetrical sounding piece. Sound tool 7 is designed to explore an amplified expression of walking.

Sound tool 20

Sounding tool: PVC, cardboard, cotton band

Sounding modes: amplification, sonic cluster, changing tempo

The object should be worn on the waist. It functions as a sounding piece that invites exploration of a ‘dry bouncing’ expression of walking. The sounding could be made in different ways by wearing the ‘sonic-apron’ at various speeds – slow/medium/fast – which will result in different sonic expressions.

Sound tool 12

Sounding tool: plastic headband, metal bells, knitting needles

Sounding modes: symmetrical/asymmetrical, amplification, extending, mono/stereo/surrounding, sonic point(s)

The object is intended to be worn on the head. It functions as an extended symmetrical or asymmetrical sounding piece. ‘Pointal’ sounding can be undertaken in seven ways by using the bells in the centre, right, left, left and right, left and centre, right and centre, or all three bells at once. Sound tool 12 can be modified by attaching different types of bells.

Sound tool 2

Sounding tool: rubber, metal, sandpaper, cotton laces

Sounding modes: amplification, sonic cluster, changing tempo

The object is intended to be worn on the shins. It functions as a sounding piece that amplifies the act of walking. The sounding can be undertaken in different ways by walking at a slow, medium, or fast pace. It can be also worn on the thighs, and the sonic expression can then be explored while sitting and crossing one’s legs.

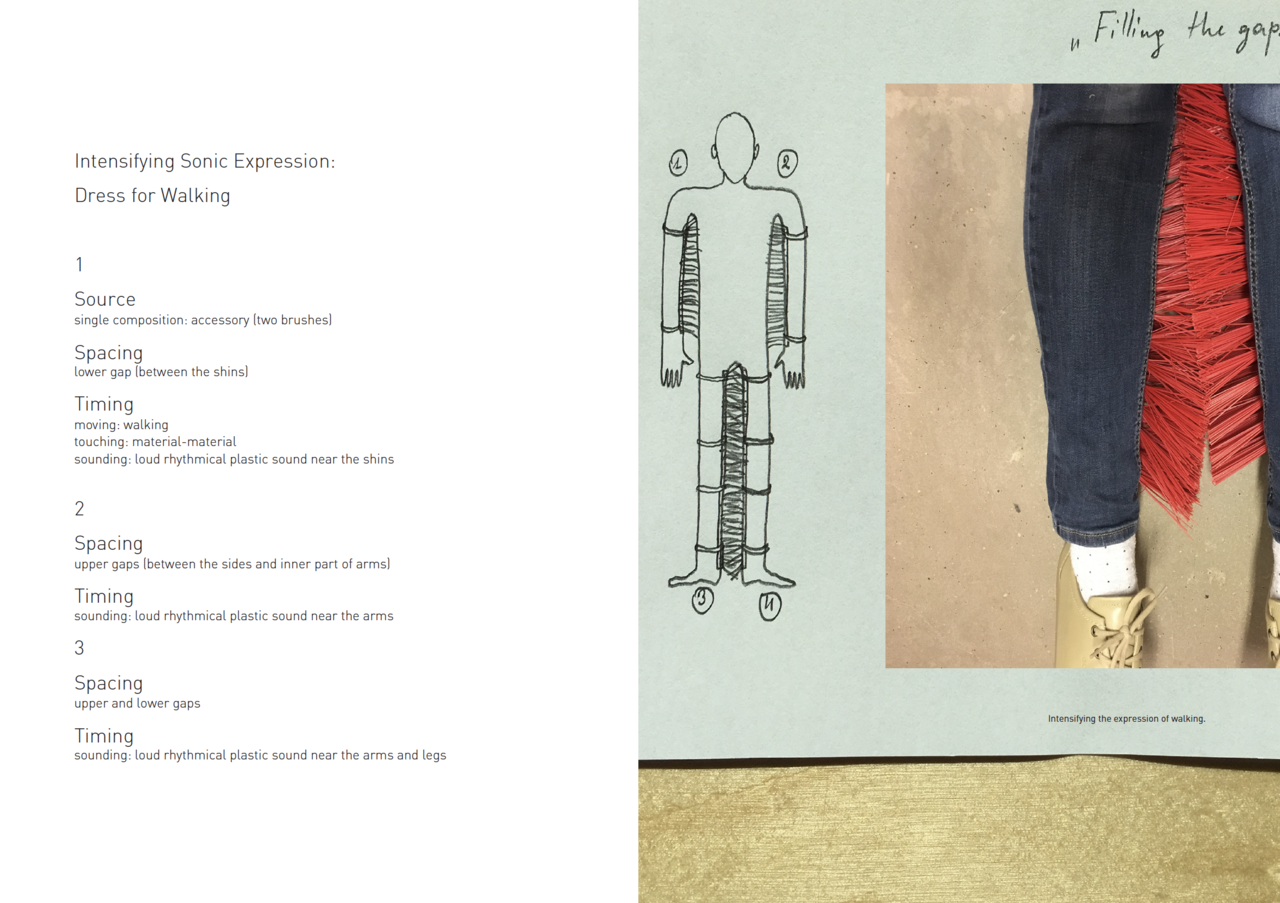

This example demonstrates the relationship between sound and bodily movements. The latter amplify the sounds of different materials. Actions such as lifting and lowering the arm, walking, and shaking and swinging the head reveal the movement of a material: sliding, floating, bouncing, etc. This and previous exercises demonstrate the possible ways in which sonic expressions can be designed whilst at the same time defining them with acts involving sound tools in use. Thus, as the temporal composition of sounding movements is varied, the ensemble of objects sounds different. The ensemble of objects is presented in the image and graphic scheme of objects on the body, which was used as a foundation for the scores.

Scores 1 - 4: instructions for performing a complex composition of sound

Body objects: 5 minutes

Content: sounds emitted by sound tools

Methods: design variables (source, timing, spacing, and acoustic), layering,

silence, volume, merging

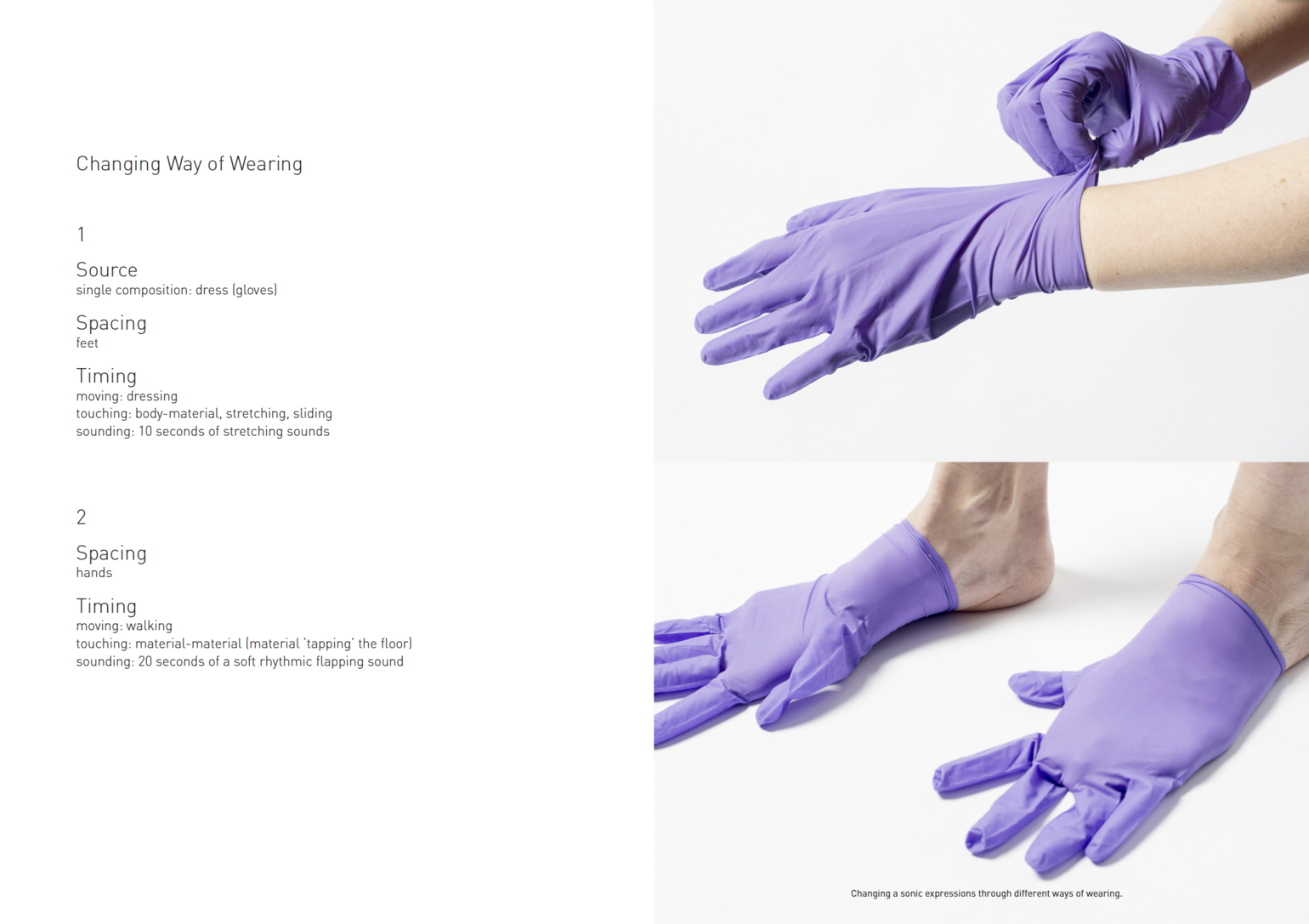

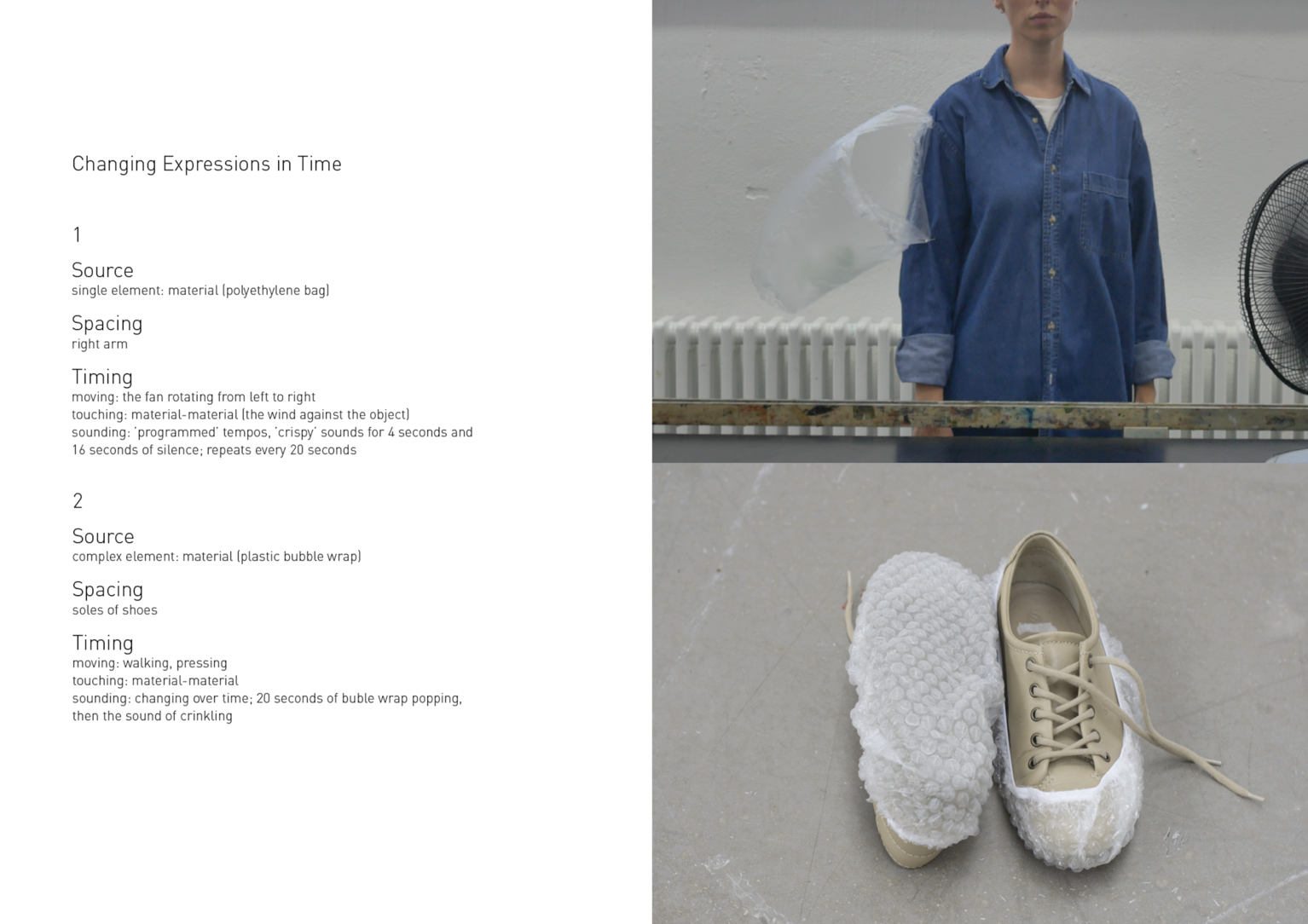

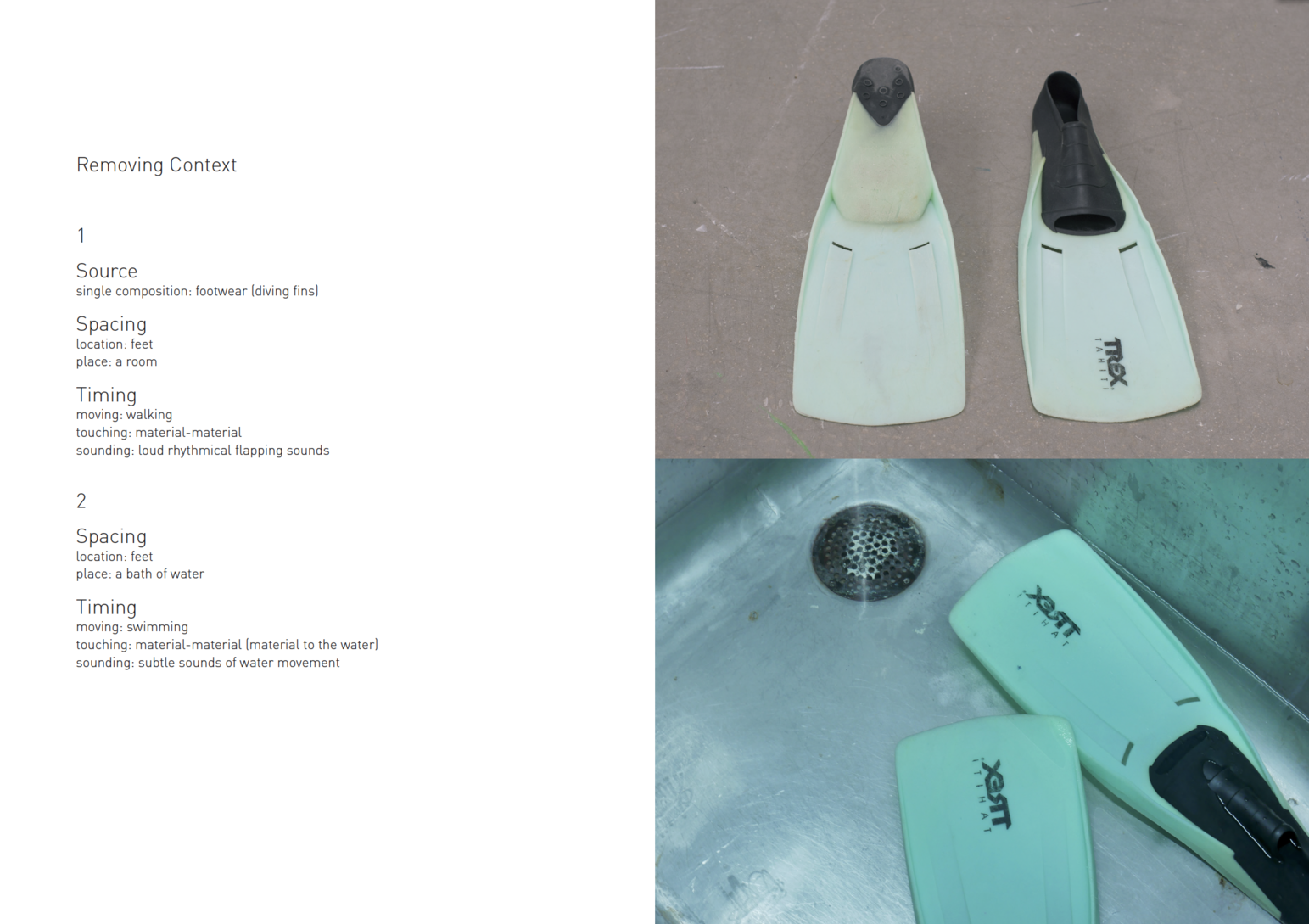

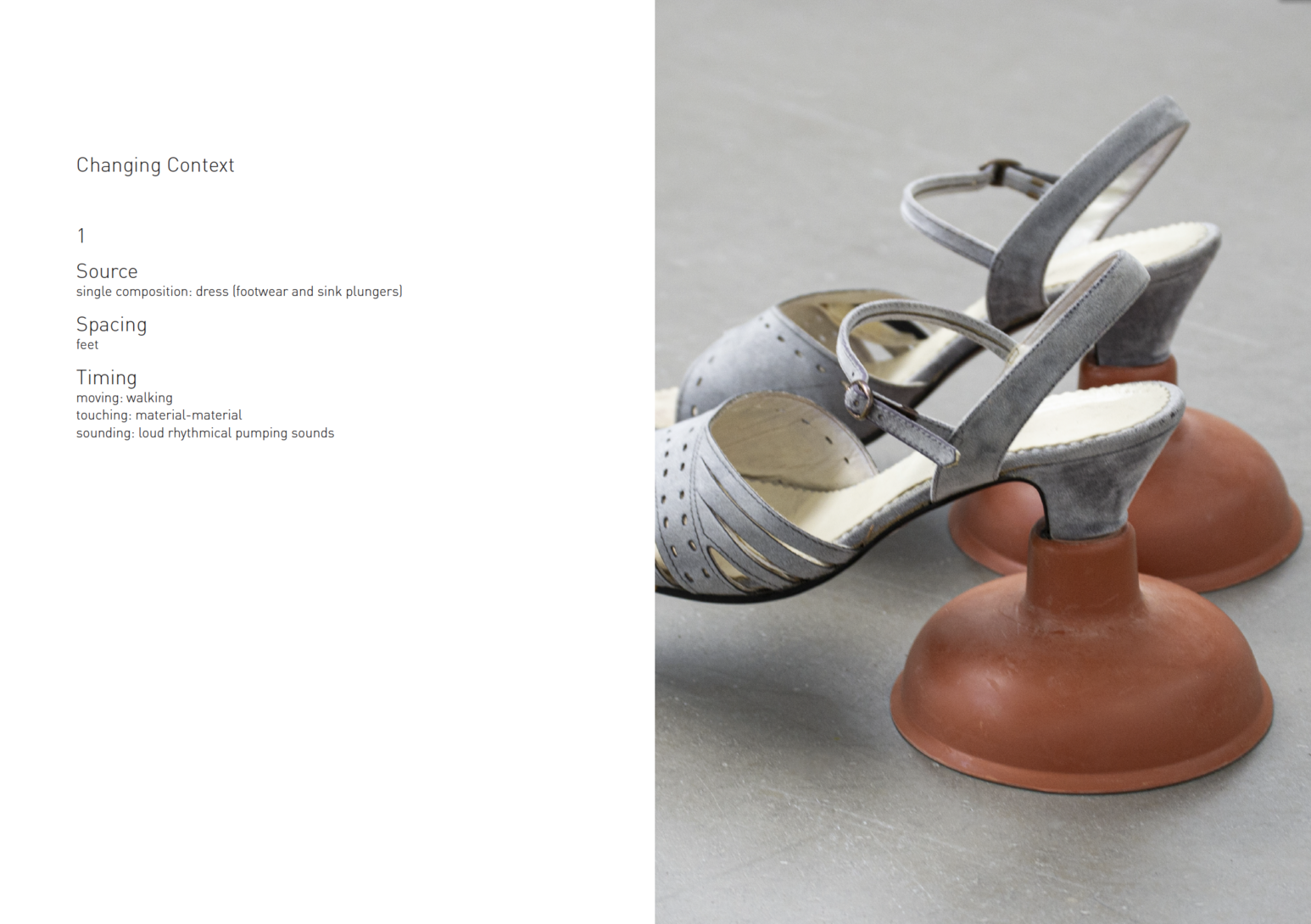

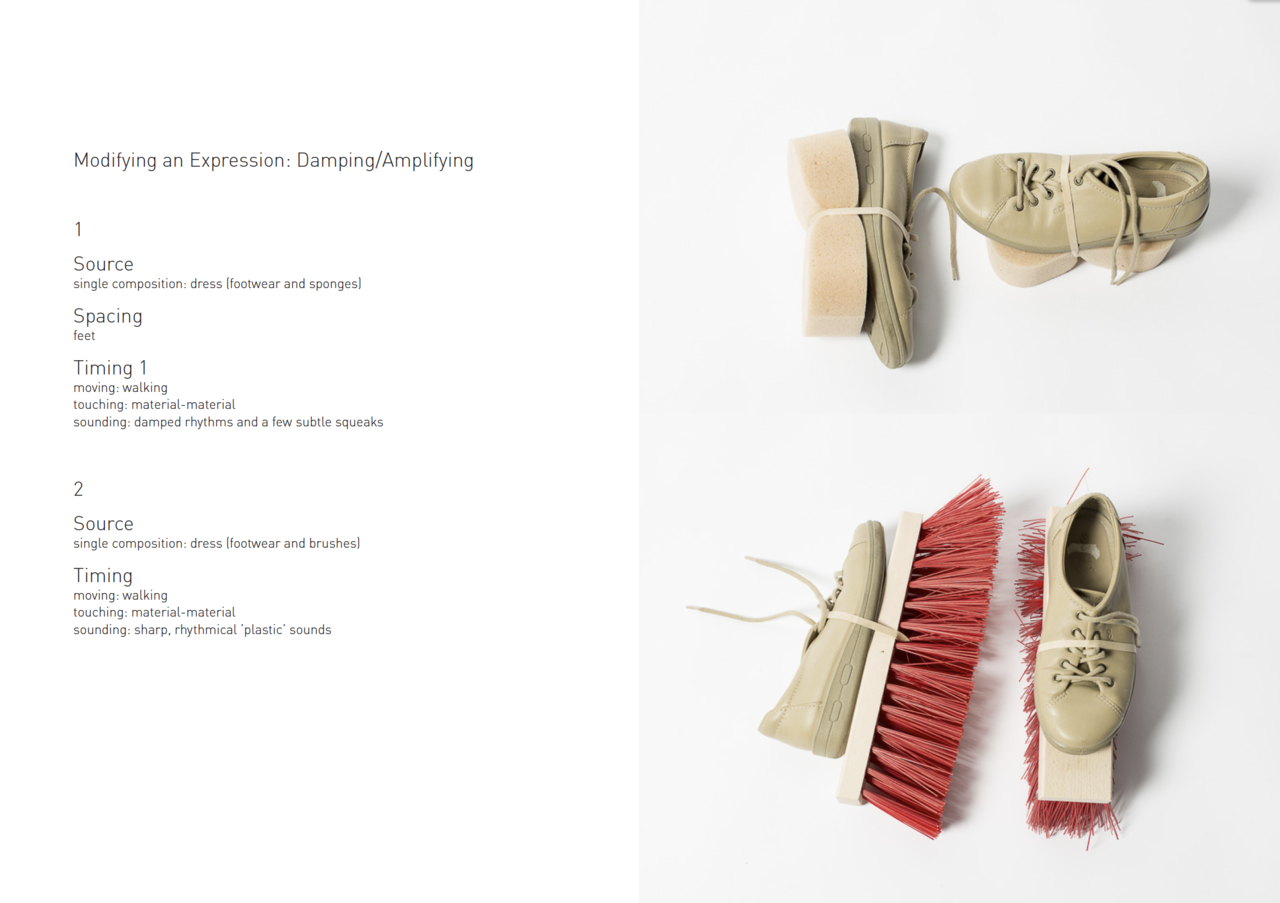

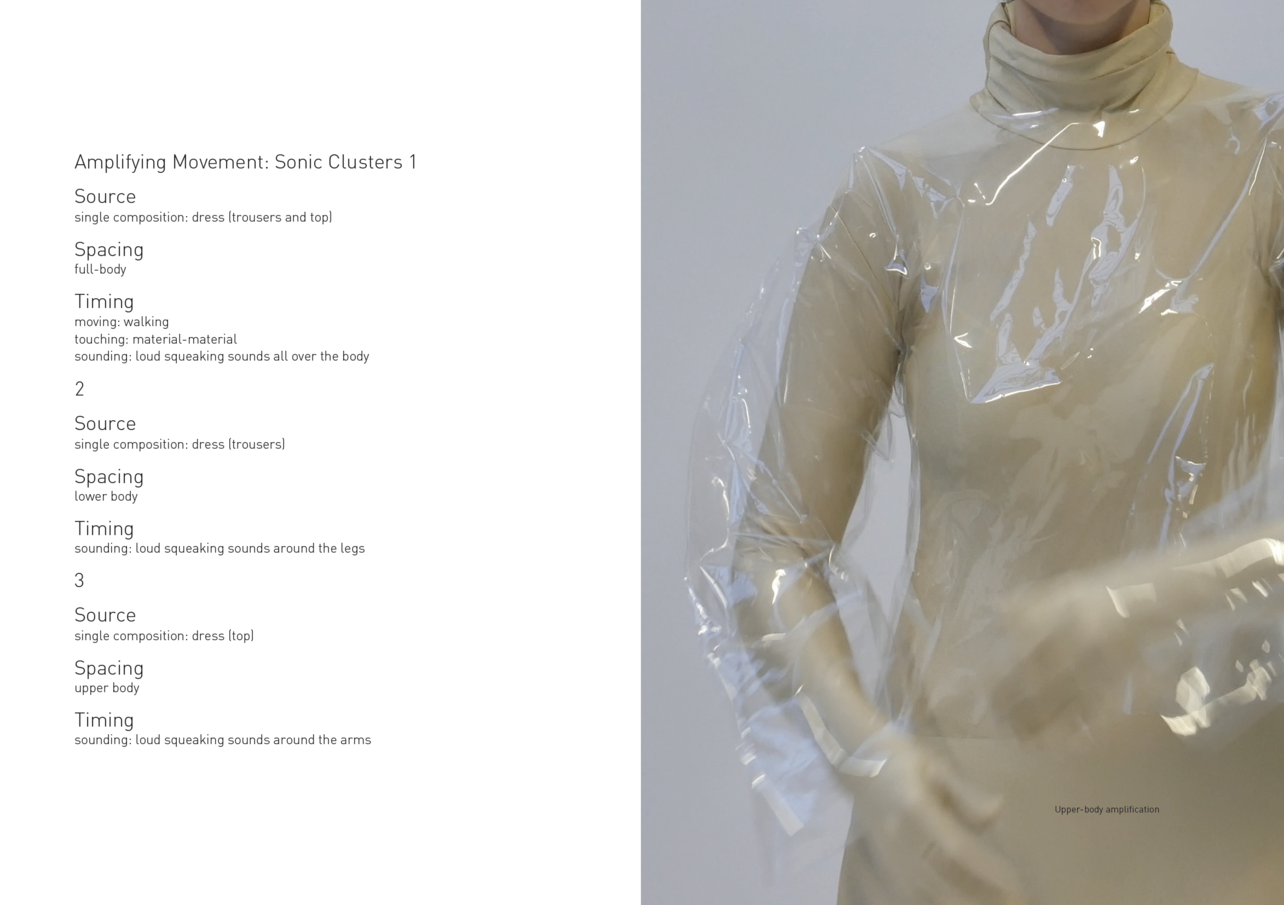

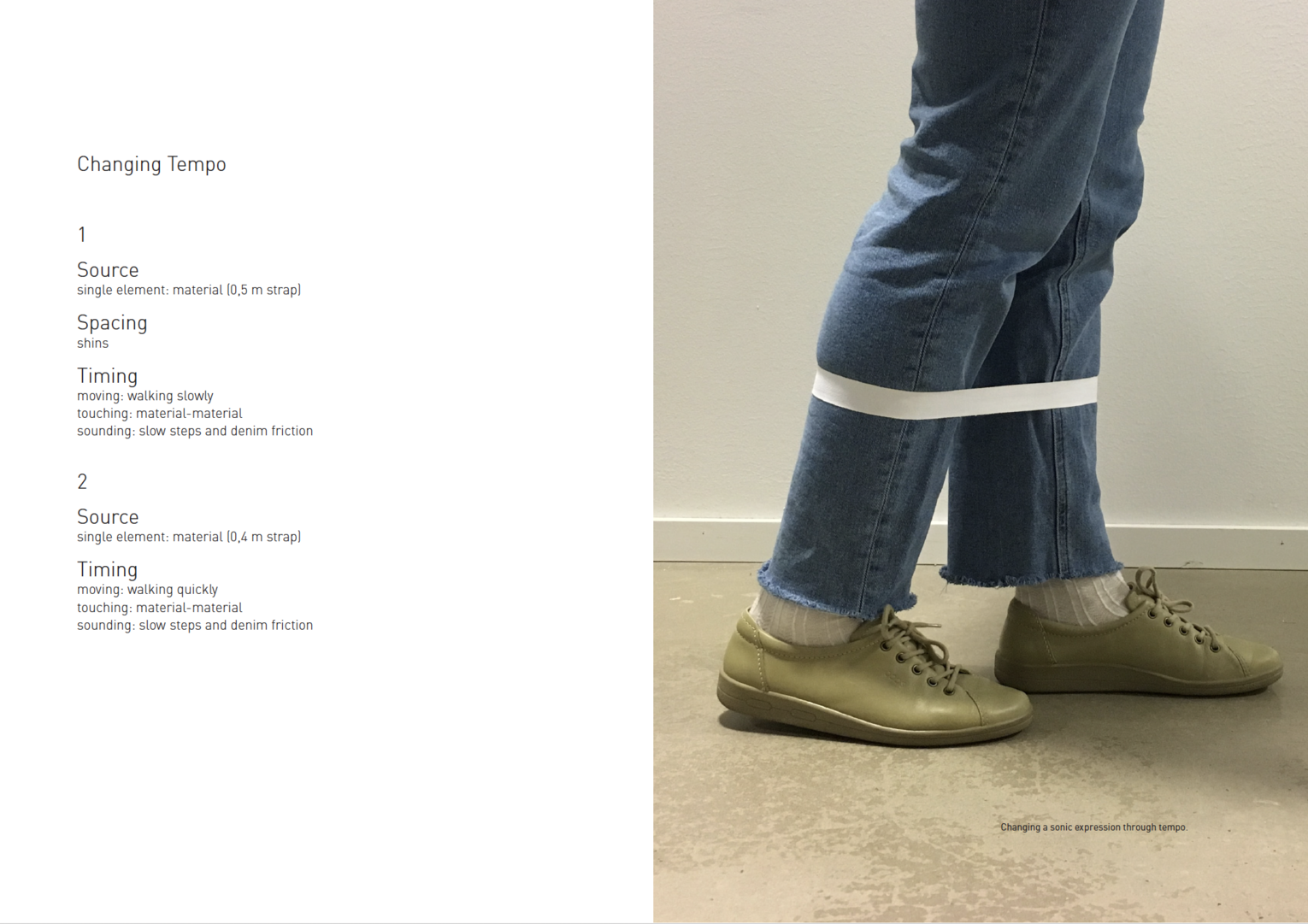

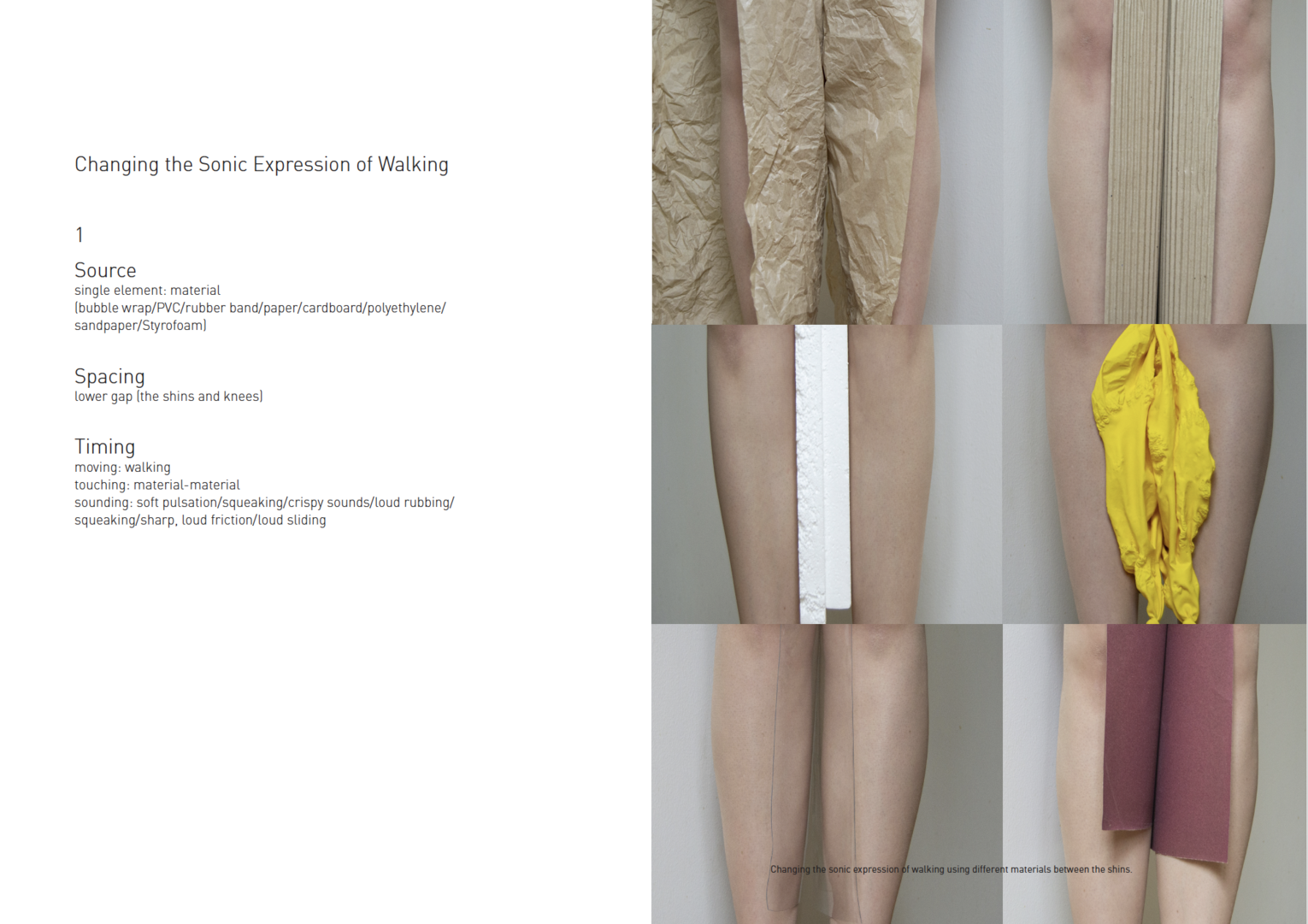

The following images demonstrate the research process as a summarized, embodied thinking with sound for developing design methods, and it is presented here with consideration for the three main design variables: source, spacing, and timing. The sound is explored as a single/complex element – material – and as a single composition – dress.

Sound tool 3

Sounding tool: shoes, bottle brushes

Sounding modes: amplification, sonic cluster, changing tempo

The object is intended to be worn on the feet. It functions as a symmetrical sounding piece. Sounding can be explored in different ways by walking in the ‘brush-shoes’ at a slow, medium, or fast pace.

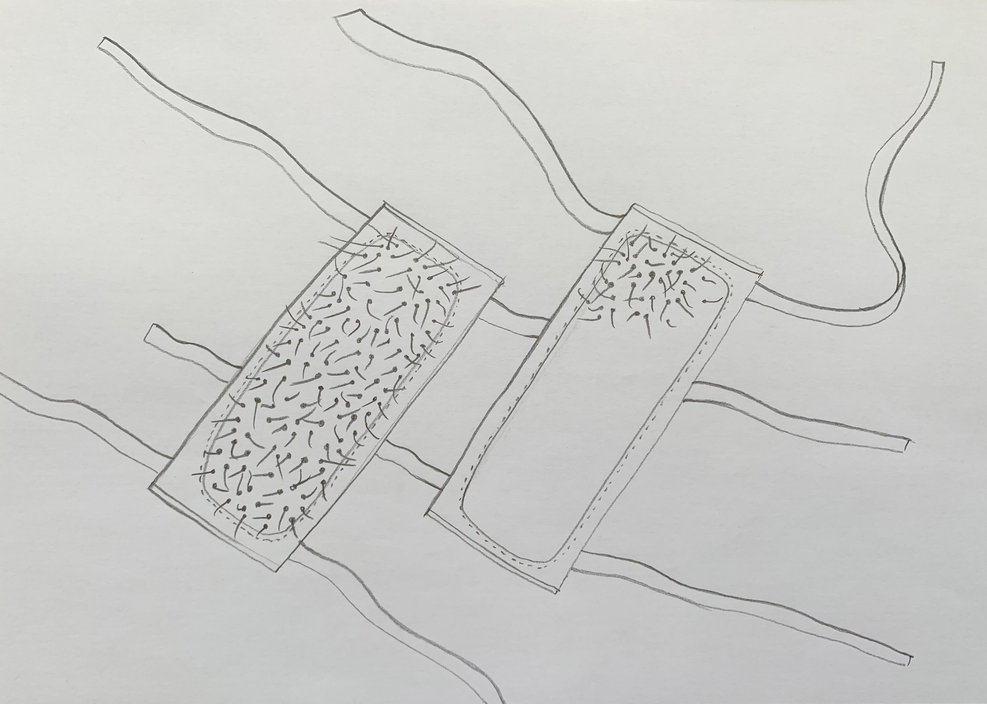

Sound tool 13

Sounding tool: PVC, metal sponges, rubber bands, magnets

Sounding modes: symmetrical/asymmetrical amplification, mono/stereo, sonic cluster(s)

The object should be worn on the foot/feet. It functions as a symmetrical or asymmetrical sounding piece.

The sounding could be made in three different ways by wearing the ‘sole(s)’ on the left, right or on both feet.

Sound tool 17

Sounding tool: PVC, rubber bands, wool, water

Sounding modes: symmetrical/asymmetrical amplification, sonic cluster(s), changing tempo

The object is intended to be worn on the arm(s). It functions as an asymmetrical or symmetrical sounding piece. The sounding can be undertaken in different ways by lifting, shaking, or rotating the arm(s) at various speeds.

Sound tool 21

Sounding tool: cap, cotton laces, paper straws, metal, glass

Sounding modes: asymmetrical amplification, surrounding, changing tempo

The object is intended to be worn on the head. It functions as an asymmetrical surround-sound piece.

The sounding can be undertaken in different ways by rotating the head or bending the neck at a slow, medium, or fast pace.

Sound tool 8

Sounding tool: cardboard, cotton, rubber bands, metal, salt, metal balls

Sounding modes: symmetrical/asymmetrical amplification, sonic cluster(s), changing tempo

The object is intended to be worn on the arm(s). It functions as a symmetrical or asymmetrical sounding piece. One of the objects is filled with salt and another contains three metal balls. The sounding can be undertaken in different ways by lifting, shaking, or rotating the body part on which it is being worn at various speeds.

Sound tool 4

Sounding tool: metal plates, springs, ping-pong and wooden balls,

rubber bands

Sounding modes: symmetrical/asymmetrical, amplification, mono/stereo,

sonic point(s)

The object is intended to be worn on the ankle(s). It functions as a symmetrical or asymmetrical sounding piece. Sounding can be undertaken in three different ways by wearing the ‘ball-anklet(s)’ on the left foot, the right foot, or both feet. One suggested way to explore Sound tool 4 is to wear it in different spaces on various surfaces.

Sound tool 18

Sounding tool: metal, knitted cotton, cotton laces

Sounding modes: amplification, sonic cluster, changing tempo

The object should be worn on the ankles. It functions as a sounding piece that amplifies walking. The sounding could be made different by wearing the Sound tool 18 at various speeds: slow/medium/fast.

Sound tool 14

Sounding tool: rubber band

Sounding modes: changing tempo

The object is intended to be worn on the shins. It functions as a tempo changer, resulting in different sonic expressions of walking.

Sound tool 9

Sounding tool: shoes, sink plungers

Sounding modes: symmetrical/asymmetrical, amplification, mono/stereo

The object is intended to be worn on the foot/feet. It functions as a symmetrical or asymmetrical sounding piece. The sounding can be undertaken in three different ways by wearing the ‘plunger shoes’ on the left foot, the right foot, or both feet. One suggested way to explore Sound tool 9 is to wear it in different spaces on various surfaces.

Sound tool 5

Sounding tool: plastic hand band, salt, metal tube, rubber, cotton band

Sounding modes: asymmetrical amplification, changing tempo

The object should be worn on the head. It functions as a sounding piece that allows exploration of the movement of sound while laterally bending the neck. As a result, the salt slides inside the metal tube. One suggested way to explore Sound tool 5 is to move the neck at different speeds.

Sound tool 10

Sounding tool: wool, cotton, rubber pumps, rubber bands

Sounding modes: symmetrical/asymmetrical amplification, sonic cluster(s), changing tempo

The object should be worn on the buttocks. It functions as a sounding piece that invites exploration of the amplified sonic expression of sitting. One suggested way to explore sound tool 10 is to sit down at different speeds: fast/medium/slow.

Sound tool 22

Listening tool: polyester, PVC, Velcro, cardboard, zipper

Listening modes: acousmatic, damping

The body should go inside the object so it functions as a ‘sound box’ that modifies the wearer’s sense of hearing and perception of a soundscape by damping sound. Sound tool 2 could be used in the acousmatic listening mode by wearing an eye covering to reduce vision.

Sound tool 25

Listening tool: plastic, metal

Listening modes: amplification, direction, stereo/mono

The object is intended to be worn on the ears as headphones and functions as a sound-modification piece that changes the wearer’s sense of hearing by amplifying and directing sound. Sound tool 6 could be used to direct and filter sound on the right or left by removing one of the cones.

Sound tool 27

Listening tool: flip-flops and foam

Listening modes: changing height

The object is designed for the feet; one should stand on the object and explore the sounds heard while listening from 0.5 metres higher than usual. One suggested way to explore Sound tool 5 is to use it in different spaces and environments.

Sound tool 29

Listening tool: plastic, foam, metal

Listening modes: amplification, isolation, stereo/mono, direction

The object is intended to be worn on the ears like headphones and functions as a sound-modification piece that changes the wearer’s sense of hearing by amplifying, directing, and isolating sound. Sound tool 3 could be used in different ways to direct and filter sound from above, below, and to the right or left. It could also be used for listening to oneself by connecting the ‘tubes’.

Sound tool 23

Listening tool: PVC, fur, knitted cotton, metal

Listening modes: damping, blocking, amplification, stereo/mono

The object is intended to be worn on the neck and functions as a sound-modification piece. It modifies the wearer’s sense of hearing and perception of a soundscape by blocking, damping or amplifying it.

It is double-sided; one side absorbs sound and another reflects it. Sound tool 1 can be used as the wearer wishes: to block one or both ears, or to cocoon the head by lifting the edges above the head.

Sound tool 28

Listening tool: plastic, metal, cardboard

Listening modes: co-listening, filtering, amplification

The object is intended to be worn on the head. It functions as a sound modification piece that changes the wearer’s sense of hearing by amplifying and filtering sounds. Sound tool 8 is designed for co-listening (listening in pairs).

Sound tool 26

Listening tool: plastic, metal, cardboard

Listening modes: amplification, direction, stereo/mono

The object is intended to be worn on the ears as headphones and functions as a sound-modification piece that changes the wearer’s sense of hearing by amplifying and directing sound. Sound tool 7 could be used to direct and filter sound on the right or left by removing one of the cones.

Sound tool 24

Listening tool: foam and knitted cotton

Listening modes: damping, blocking

The object is intended to be worn on the head or neck and functions as a sound-modification piece that changes the wearer’s sense of hearing by damping/blocking sound. Sound tool 4 could be used in different ways to block sounds coming from above, below, ahead, and behind.