Richard Barrett

NEW INPUTS

Research report January 2022

Supported by the lectorate ‘Music, Education and Society’, research group ‘Making in Music’, Royal Conservatoire The Hague

section 1: prelude

The initial question addressed by this research project, following on from my 2019 project A Year in the life of the Sonology Electroacoustic Ensemble (Barrett 2020), was rather simple: “how can improvisational practices in other disciplines inform and expand on the ideas and models available to discuss free improvisation in music with a particular view to using it in a teaching context?”

Accordingly, I’ve been researching the areas of theatre, dance and visual art, in order to search out “new inputs” into musical improvisation. In addition, I included in my survey some possible new inputs from within music and sound art itself, for example the particular characteristics of musical technologies such as no-input mixing and how these demand and/or suggest new ways of musical thinking, as a means of generalising my question to express the idea that for the improvising musician there is no such thing as an “extra-musical” influence, since the music is potentially open to any possibility. Nevertheless, many fascinating insights have been gained from the research which seem to have much potential for working with musical improvisation in the conservatoire. And when I use the formulation “working with musical improvisation”, it has also become increasingly clear that this applies not only to music whose principal creative method is improvisation in real time, but also to music where improvisational thinking alternates or interweaves with other methods. I’m not concerned with “teaching improvisation” in the sense that this is often encountered in educational institutions, and which leads more often than not to music that sounds half-baked, consisting of familiar genres mixed together with an awkwardness that doesn’t do justice to any of them, let alone to the idea of the unique possibilities of the spontaneous imagination; and for me it’s at least as important to communicate the idea that improvisational thinking has a potentially central role to play in many other compositional strategies, and that concepts encountered in or arising from improvisation, more often than not, provide valuable insights into those other strategies (and of course vice versa).

I’ve come across many concepts, themselves tested in the crucible of real collaborative work, which to my knowledge are seldom explicitly applied in the context of free improvisation in music, however simple they may seem – to give a brief example from the writing of Keith Johnstone, a pioneer in improvisational theatre, “[t]he improviser has to understand that his first skill lies in releasing his partner’s imagination.” (Johnstone 1979, p. 93) It’s clear how such an idea can be explained and realised in the context of spoken drama, and it’s also clear that it plays an important role in the rather different kinds of interaction involved in musical performance, and it would almost certainly be fruitful to develop ways of isolating and activating this particular “skill” with an improvising group of student musicians.

It will be apparent that I’m by no means an expert in most of the subjects I’m researching here, and I apologise in advance for any factual or conceptual inaccuracies resulting from the necessary superficiality of my approach; if I have an excuse, it’s that my almost exclusive focus is in what I think can be of use in a musical context, even if in the course of my investigations I’ve still discovered much fascinating material, worthy of much more extended exploration, which will have to take place another time and in another context. I’m “improvising through” my subject matter in perhaps an analogous way to John Cage’s “writing through” Finnegans Wake and other texts, though without the poetic dimension that emerges from Cage’s chance procedures.

I’m concerned here not so much with drawing together preexistent treatments of relationships between music and other artistic disciplines, of which there are many, although much fewer that concentrate on improvisation, but in looking at a personal selection of some examples of what’s been described in terms of improvisation in other artforms, or is recognisable as such, and drawing from these ideas and possibilities which can be applied directly in a musical context and especially in a pedagogical one. Often, improvisation in these other artforms is already described by practitioners and commentators in terms of music, most often referring more or less insightfully to jazz improvisation. For example, the element of (actual or recorded) spontaneity in much 20th century poetry tends to be related by its practitioners to musical models, as Benjamin Lee observes: “[m]uch experimental poetry of the 1950s and 1960s, particularly in the United States, was devoted to some notion of improvisation. This was due in large measure to the energy, dexterity and cultural cachet of bebop, which in the decades before rock ‘n’ roll managed to signify both youthful rebellion and high modernist difficulty.” (Lee 2012, p. 75) While such manifestations of one artform being treated as a metaphor for another are often of great interest, they haven’t generally been included here unless they seemed to me to furnish the potential to inform musical improvisation in new, unfamiliar and above all practically useful ways.

I wrote in my previous report (Barrett 2020) about why I believe free improvisation to be a potentially important activity in musical education; while many musicians (including myself, some considerable time ago!) have no hesitation or problem in taking their first steps into this world of musical possibility, others might find it daunting or on the other hand trivial. The connections proposed in the present text are intended in part to help address such issues. But, more importantly, they might also serve to outline an extensive network of ideas and practices coming from many sources and directions, concerning what improvisation is, how it works, and how it might relate to other strategies, which could inform and enrich the creativity of improvising musicians. Much writing on improvisation makes a valiant but in my opinion ultimately doomed attempt to talk about its subject in general or abstract terms. One of the priorities of this text is to stay close at all times to actual music-making, including music that hasn’t yet been made. Improvisation is what happens, not what you think (is happening).

I had been hoping to organise a symposium in November of 2020 to bring musicians and other artists together in a concrete realisation of some of the ideas on which the research has been based. This plan was eventually partially realised in the form of an online seminar. I had also planned throughout 2020 to test the applicability of the “new inputs” I had encountered and developed in the context of my work with the Sonology Electroacoustic Ensemble (SEE). The eventual research output was therefore intended to consist not only of theoretical reflections on my findings, and speculation on their possible applicability to actual musical situations, but also of documentation of a process of experimentation through which those findings could be tested and assessed, and indeed through which the eventual shape of the present text might have ended up taking quite a different form. Since I’m already making considerable use of my 2019 research output in my teaching activity (especially within the new Collaborative Music Creation elective at the KC), I was intending that a comparable combination of text and sound would be the most useful way to encapsulate the results of my work. In the event, this aspect had to be abandoned during 2020. On the other hand, the enforced isolation of my own musical activities during that year and the following one led in some unexpectedly productive directions relevant to several of the issues indicated by my original research question, so I’ve included accounts of some of these also, in view of the priority mentioned above. During 2021, it has been possible to put into practice some of the ideas explored in the “theoretical” phase of this project, although the results didn’t always go in the directions I might have anticipated.

The present text, therefore, combines this first phase with discussions of the practical results of the second phase, some of the latter being incorporated into the body of the text where they relate most specifically to issues treated in the former, while others are discussed in the concluding section 8. This has resulted in a somewhat patchwork-like text whose structural awkwardness will, I hope, be addressed in the third and final phase of this research over the first half of 2022 which will involve restructuring these and other materials into the form of a book.

On 3 November 2020 I organised an online seminar to which I invited 14 speakers, all of whom are improvising musicians whose work is informed by various kinds of contacts and collaborations with artists in other disciplines:

Magda Mayas (pianist, Berlin)

Simon Rose (saxophonist, independent researcher and author, Berlin)

Michael Vatcher (percussionist, Amsterdam)

Anne La Berge (flutist and composer, Amsterdam)

Stefan Prins (composer and performer, Hochschule für Musik “Carl Maria Von Weber”, Dresden)

Maggie Nicols (vocalist, dancer and freelance educator, London)

Peter Jacquemyn (contrabassist and visual artist, Brakel (BE))

Semay Wu (composer, cellist, media/sound artist, Glasgow)

Ranjith Hegde (violinist and composer, Chennai)

Ute Wassermann (vocalist, composer and sound artist, Berlin)

Johan van Kreij (composer, performer and researcher, Institute of Sonology)

Karst de Jong (pianist, music theorist and educator, Royal Conservatoire The Hague and Escola Superior de Musica de Catalunya, Barcelona, visiting professor at the Yong Siew Toh Conservatory of the National University of Singapore)

Hannah Marshall (cellist and theatre maker based in London)

Each guest gave a brief presentation on their connection to the subject, and more than half of the entire duration was given over to discussions between them, moderated by myself. Hannah Marshall was unable to attend the seminar but agreed to send me a contribution in written form and answer some follow-up questions.

The present text comprises sections focusing on the visual arts (section 2), theatre, film and video (3), dance and physical theatre (4), technology (5), the online seminar (6), recent improvisation workshops (7), and some new ideas and possible next steps (8). There are of course overlaps and some blurring between categories 2-5. The 17 “compositions” distributed through those sections in the form of brief descriptions of musical actions and structures will, I hope, serve to illustrate some of the possibilities for addressing the original question of this research, each as an example of a way of thinking that might encourage readers to imagine their own “translations” of improvisational ideas and practices into music. They are intended primarily as exercises or sources of ideas that might be worked on in rehearsals or workshops, perhaps in preparation for a performance which will then discard them and be freely improvised. Each composition consists of an open-ended set of suggestions, which in an actual workshop or rehearsal might be supplemented or changed. Some possibilities for extending the focal concept of a composition are given for most of them, although these in turn might serve as a starting point for further development, or different directions might be taken, according to improvisational responses to the momentary situation on the part of the workshop/rehearsal leader and/or any other members of the group.

It was, as I mentioned above, originally my intention to work on these compositions over the course of 2020 with SEE, which would no doubt have involved their further development, perhaps in some cases replacement by new ideas emerging from practice. The absence of this dimension of the research during 2020 meant that I had more time and space to spend on the theoretical side of the work, and to give the imagination free rein for speculative thinking, and, with the somewhat increased practical opportunities which opened up during the second half of 2021, I was able at least in part to test those speculations under real-life conditions. At the same time, it became increasingly clear to me that the conditions under which I’d been working on compositional projects during the entire 2020-21 period had brought more sharply into focus the synergies between systematic and spontaneous thinking, actions and reactions in my creative work, to the point that those conditions constituted a further and unexpected “new input” with implications for both educational and creative activities. Perhaps paradoxically, I’ve also come to view my creative and educational activities as more closely integrated than I had previously appreciated. (See section 8 below.)

As a musical component in this prelude to my survey of “new inputs”, I would like to place here a recording of the only performance by SEE in 2020, which took place at a Sonology Discussion Concert in the Arnold Schönbergzaal of the Royal Conservatoire on 26 January. The participants were

Richard Barrett - keyboard/computer

Júlia Casañas Castellví - viola

Dariush Derakhshani - live coding

Marcela Andrea León García - piano

Ranjith Hegde - electric violin

Myrtó Nizami - piano

Marko Uzunovski - live mixing

This would have been the basis of the group participating in the practical components of the present research project if it had taken place in 2020. I found it one of the most engaging performances of recent years in its confident sense of structural consistency and development. The experience of working with these creative musicians and other participants in SEE has been a central influence, and the central inspiration, behind the work documented here, so many thanks are due to those named above and everyone else who has participated in the ensemble over the past eleven years. I would also like to thank all the seminar participants; Paul Craenen and Roos Leeflang for their crucial support, suggestions and thoughts over the last three years; Kees Tazelaar for encouraging and facilitating the inception and development of SEE (occasionally also as a player!); Henk van der Meulen and Martin Prchal for their essential roles in making this project possible; Paul Obermayer for countless crucial insights, and for 36 years (and counting) of shared exploration of music and much more; and Milana Zarić for reading and suggesting many improvements to this report, as well as for her crucial creative contribution to the musical component of the research, and for the love that makes everything possible.

section 2: visual art

When looking at what the visual arts might have to offer in terms of ideas that would “translate” into concepts applicable to musical improvisation, I thought it seemed appropriate to begin with the work of Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), since he made his celebrated transition from figurative towards abstract art principally through a long series of over 200 paintings made between 1909 and 1917, which he entitled Improvisations.

Kandinsky, Improvisation no.11

Of course, Kandinsky was concerned throughout his creative life to establish parallels between painting and music, and numbered Arnold Schoenberg among his friends and associates. Kandinsky explains and contextualises his use of the term “improvisation” in his book On the Spiritual in Art as one of three “different sources of inspiration” in what he calls his “symphonic” (as opposed to the simpler “melodic”) works:

-

A direct impression of “outward nature”, which is expressed in pure artistic form. These pictures I call “impressions”.

-

Intuitive, for the greater part spontaneous expressions of incidents of an inner character, or impressions of the “inner nature”, this kind I call “improvisations.”

-

With slowly evolved feelings, which have formed within me for a long time, and tested pedantically, developed after they were intuitively conceived. This kind of picture I call “compositions”. (Kandinsky 1946, p.98)

Kandinsky, Improvisation no.35

Improvisation no.11 forms the front cover image of the first English publication of Kandinsky’s book. In many cases this process of improvisation throws up familiar shapes and figures alongside elements that seem to involve a more “pure” deployment of colour and line, as can be seen from the examples above. Kandinsky’s description clearly emphasises the “intuitive” and “spontaneous” aspects of improvisation, as opposed to the depiction of nature or the expression of the more reflective side of the imagination in his other two categories. Kandinsky seems to have regarded what he called improvisation as a method of escaping from figurative painting, as John Gilmour observes:

Improvisation plays an essential role in altering composition practices, Kandinsky thinks, because it is a way to move toward “the free working of color” rather than treating color as derivative from nature. (Gilmour 2000, p.191)

I’ve always felt that musical improvisation can in a comparable way move towards a “free working of sound”: any tendency to rely on received ways of relating sounds to one another, specifically when working in a group, is usually unhelpful, so that the result can often sound like an impoverished version of more traditional musics but (for example) with an undeveloped sense of harmony or rhythm or form. As in Kandinsky, improvisation might actually be characterised as (the trace of) a search for new kinds of structural and expressive relationships between sounds.

Something that can clearly be seen when looking at Kandinsky’s “improvisations” is his concern that each of them should, while preserving its sense of spontaneity, have a distinct character of its own, so that for the most part they are no less memorable and recognisable than the products of his other imaginative methods. There is always an obvious concern with the overall form of the painting, and some defining colour scheme or shape or “motif” forming one or more central ideas around which the rest of the painting is organised. Is this aspect something that belongs particularly to the painting as the work of an individual rather than a collective, which doesn’t have to articulate itself spontaneously inside-time like a musical improvisation does? While the identity of an improvised piece of music isn’t often characterised in this way unless it’s based on some preexistent notated or agreed material, that doesn’t mean it couldn’t be.

Composition 1

Before starting to play, look closely at a Kandinsky

“improvisation” and identify its defining colour scheme, shape or motif.

Think of an analogously identifiable and memorable colour, shape or

motif in musical terms. Then play. Everything you do should express this

colour, shape or motif in some way, varying it in response to what the

other participants are doing but always relating to it. Possible

extensions of this idea could include replacing one’s own colour, shape

or motif with (a variation on) someone else’s as heard, or adding

someone else’s to one’s own. Such extensions could form the basis of a

structural process for the piece.

Of course, unlike a musical improvisation, all we see of Kandinsky’s process is the result, however unplanned and “intuitive” the process itself might have been. It isn’t really possible in principle to retrace the steps of the process any more than with Kandinsky’s other two “sources of inspiration”, even if the painting does carry strong traces of the spontaneity of the process, in comparison with the generally more clearly defined and often more geometrical quality of his “compositions”. The result seems more closely related to the spatialisation of time involved in musical notation than to the centrality of the process in improvisation. After all, Adorno asserts in an essay on music and painting that:

the act of notation is essential to art music, not incidental. Without writing [there can be] no highly organized music; the historical distinction between improvisation and musica composita coincides qualitatively with that between laxness and musical articulation. This qualitative relationship of music to its visible insignia, without which it could neither possess nor construct out duration, points clearly to space as a condition of its objectification. (Adorno 1995, p.70)

This position is to be rejected if the existence of improvised music is taken seriously. But if Adorno’s citing of notation as a way in which music as Zeitkunst takes on through notation some of the character of painting as Raumkunst is seen for the limited view that it is, we can find another kind of “musical space” in György Ligeti’s discussion of form in contemporary music:

“Form” is originally an abstraction of spatial configurations, of the proportions between the extensions of objects in space. Transferred to non-spatial domains – the form of poetry or of music – “form” becomes an abstraction of an abstraction. In accordance with the provenance of the term, spatiality remains attached to forms which unfold in time, supported by the fact that time and space are always coupled with one another in the world of our thoughts and imaginations; wherever one of the two categories is present, the other appears immediately by association. In the act of conceiving or hearing music whose sonic progress is primarily temporal, imaginary spatial relations emerge on several levels, initially on the level of association, as changes in pitch (the German word Tonhöhe already contains a spatial analogy) evoke the vertical spatial dimension, the persistence of a particular pitch evokes a horizontal one, while changes in timbre and intensity, such as differences between open and muted sounds, produce an impression of proximity and distance, a general impression of spatial depth. Musical figures and events appear to us to take up certain positions in the imaginary space which they themselves evoke. … [B]ecause we spontaneously compare any new moment that appears in our consciousness with moments already experienced, and on the basis of this comparison draw conclusions about what is to come, we pass through a musical edifice as if its structure were present as a totality. The interaction of association, abstraction, memory and prediction is a prerequisite for the formation of the network of interrelations that enables the conception of musical form.

From this viewpoint we can characterise the difference between music as such and musical form: “music” would thus denote the pure temporal process, while “musical form”, conversely, would denote the abstraction of that same temporal process, whose internal relations present themselves in terms not of temporal succession, but of virtual space; musical form emerges only when the temporal course of musical events can be viewed retrospectively as “space”. (Ligeti 2007, p.186, my translation)

And if Ligeti’s characterisation of music as evoking a “virtual space” within the listener’s mind has any truth to it (which for the present writer it certainly does), and if this is as applicable to improvised music as to the notated music which both Adorno and Ligeti had in mind (which it surely also does), then is it possible to look back at something like Kandinsky’s “improvisations” and see in them some kind of “virtual time” which we can relate fruitfully to the practice of musical improvisation, whether or not this “virtual time” has any relation to the (unknowable) inside-time process by which it reached the form it now permanently has? Perhaps it would be possible to trace the itinerary our eye takes through a Kandinsky painting (or any other, of course) and lay this out somehow as a “score” which would express the passage of this “virtual time”. Of course, many improvising musicians have created performances by “reading” paintings as if they consisted of “graphic notation”, but this isn’t what I have in mind, because in that case it wouldn’t be very long before the eye’s itinerary, its tendency to dwell on certain regions for example, would be dictated by considerations of making an interesting piece of music with a certain overall duration. What I have in mind is *discovering the music IN the painting, ***and only then imagining what it might sound like, or not. (I wonder if this procedure might also be applied to some arbitrarily chosen musical score!)

Many of these considerations might of course apply to any painting by any artist, or indeed any visual stimulus whatever. But another visual artist in the context of whose work the idea of improvisation has been explicitly invoked is Paul Cézanne (1839-1906). “Cezanne’s [improvisations] have to do with interpretations of impressions.” (Gilmour 2000, p.191, emphasis in the original.) Improvisation here seems to consist in going repeatedly to the same viewpoint and painting the same landscape but each time with a different more or less spontaneous variation which goes beyond any external differences in light or weather, as a result of the sensory input from the experience being so rich and complex that each painting of it has to involve what in audio terms would be termed filtering, in order to render some particular “interpretation” onto the canvas:

[In a 1906 letter, Cézanne] writes as if he is so immersed in the natural setting that its richness of color becomes almost overwhelming when he tries to realize it in paint. In addition, his comment that “the motifs multiply” indicates his belief that nature’s plenitude calls forth many alternatives for the painter. (Gilmour 2000, p.192)

[And in 1904:] to read nature is to see it, as if through a veil, in terms of an interpretation in patches of color following one another according to a law of harmony. These major hues are thus analyzed through modulations. Painting is classifying one’s sensations of color. (Gilmour 2000, p.194, my emphasis)

To illustrate these ideas, here are two paintings by Cézanne of the same landscape from almost the same viewpoint: Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves.

The workings of improvisation might be seen in Cézanne’s different reactions in colour and design to the same situations – choosing, supposedly in the moment, between the “alternatives” he refers to in the letter of 1906. David Hockney (2011) speaks in comparable terms about the way his iPad drawings involve an immediacy and speed of execution that enables him to chronicle seasonal changes in long series of rapidly executed pictures, while the luminosity of the medium suggests subjects (such as the depiction of sunrises) which wouldn’t be suited to more traditional drawing tools. This might be compared to other ways in which digital technology might suggest new approaches to improvisatory music (see section 6).

Composition 2

Prepare some kind of sonic “landscape”, perhaps in the

form of fixed-media material, consisting of brief isolated sounds or

slowly changing textures or some combination of the two but leaving

space for live performance, if necessary notating its principal events

against a timeline and/or having all participants listen to and memorise

them, then play an improvisation in which this “landscape” is repeated

several times, with the “live” contributions relating to it differently

each time, making different aspects audible or submerged or emphasised

and so on. Possible extension: leave out the original in one iteration

but make sure it’s “present” in what the group plays. Possible further

extension: leave it out altogether (landscape painting from memory

rather than from life).

Matthew Sansom, in an essay relating the Abstract Expressionist movement to free improvisation, (2001) mentions as precursors Joan Miró (1893-1983), André Masson (1896-1987) and Max Ernst (1891-1976), who developed diverse procedures on the model of the “automatic writing” (see section 3) developed around 1919 by André Breton.

These procedures, along with the use of unusual materials, discouraged deliberate control and encouraged the emergence of more unconscious imagery. Such factors provide significant similarities with the procedures of free improvisation, and the previous descriptions of automatic painting are strongly evocative of the processes of free improvisation. A description by [Cornelius] Cardew highlights this: “We are searching for sounds and for the responses that attach to them, rather than thinking them up, preparing them and producing them. The search is conducted in the medium of sound and the musician himself is at the heart of the experiment.” (Sansom 2001, p.31)

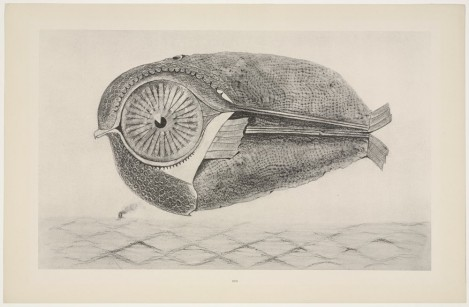

Max Ernst in particular developed several techniques such as frottage (placing paper over an uneven surface and producing a “rubbing” with a pencil) and decalcomania (pressing layers of paint against the canvas with glass or some other suitable material), to generate, while excluding all conscious mental influences, a suitably rich substrate from which an image would then be “hallucinated” by a process of free association directed towards making the unconscious visible. This is a more highly evolved version of the common phenomenon of pareidolia, in which our overdeveloped pattern-recognition abilities cause us to “see” images, and especially faces, in inanimate objects such as buildings or bathroom fittings or slices of toast. While Ernst himself didn’t speak of his work in terms of improvisation, it’s clear that much of it is concerned with using various more or less unusual techniques to create the conditions for spontaneous flights of the imagination.

Max Ernst, frottage The Fugitive (L’évadé)

Composition 3

Divide the ensemble into two equal halves. Initially,

group 1 plays a consistent texture with a certain internal complexity

(each member bearing in mind that sound materials should be chosen in a

spirit of generosity, thinking about what can fruitfully be taken up by

their colleagues in group 2). After this is established, the members of

group 2 draw implicit musical “images” from the texture, for example

taking one or more pitches audible within it and linking them together

into a melody, or making various kinds of “echoes” of perhaps accidental

sound-events in the texture. Group 2 members should think of creating

sound events clearly delineated in time and identity. On an agreed

signal the two groups exchange functions. Possible extension: each

member of the ensemble alternates individually between “substrate” and

“frottage”.

Max Ernst, The Eye of Silence (L’oeil du silence)

Several of Max Ernst’s best known paintings (The Stolen Mirror, The Eye of Silence, Napoleon in the Wilderness, Europe After the Rain) use the decalcomania technique (introduced to the Surrealists by the Spanish painter Óscar Domínguez) as the basis for oneiric landscape-like images, somewhere between organic shapes and ruined constructions, sometimes inhabited by enigmatic humanoid figures, and no doubt not unconnected with Ernst’s situation in the early 1940s, when they wer painted, as a refugee in the USA from the war that was devastating Europe. This kind of technique, as well as the imagery Max Ernst derived from it, forms the point of departure for an ongoing composition project discussed in section 8 below, in which prerecorded sound materials (themselves based on improvisation) form a substrate for improvised “interpretations”.

In a development of the kinds of techniques developed by Max Ernst, the Abstract Expressionist painters brought the process of painting to the foreground, which Sansom cites as a connecting factor between such art and free improvisation: “The emphasis upon process and material qualities enabled by ‘freedom’ from the image and more (traditionally) formal concerns is paralleled by ‘freedom’ from functional harmony and/or traditional modes of compositional construction, resulting in a direct engagement with the medium of sound and the processes of musical creation.” (Sansom 2001, p. 32, my emphasis) The way artists such as Jackson Pollock (whose work was particularly admired by Max Ernst) and Robert Motherwell describe their working process is indeed so closely related to the corresponding kinds of statement by improvising musicians that there’s hardly any possibility here to imagine the Abstract Expressionists as potentially furnishing a “new input” to improvisational thinking in music. As Bjerstedt (2014) points out:

the concept of rhythm is often employed in connection with the (more or less regular) recurrence of elements in visual representation, prominently so in works of, for instance, Pollock, Mondrian, and Miró. In this context, rhythm – like structure – is the product of visual repetition. (p. 113)

These particular inputs took place more than half a century ago and contributed crucially to how musicians conceived freely improvised music from its beginnings. Here for example is the guitarist (and artist) Keith Rowe, as a founding member of the AMM group one of the pioneers of free improvisation in the 1960s, describing his switch to what became known as “table-top guitar” or “prepared guitar” technique with direct reference to Pollock placing the canvas on the studio floor:

Suddenly trying to play guitar like Jim Hall seemed quite wrong… Who am I? What do I have to say? I probably thought about that for between five and eight years, just constantly reflecting on how to do it, and, in a flash, I found the solution. Look at the American school of painting, which was very provincial in the 1800s: they really wanted to do something original but didn’t know how to do it, the clue was to get rid of European painting, but how could they ditch European painting, what did they have to do to do that? And Jackson Pollock did it – he just abandoned the technique. How could I abandon the technique? Lay the guitar flat! All that it’s doing is angling the body [of the guitar] from facing outwards to facing upwards – the strings remain horizontal, the strings are the same. (Rowe 2001, n.p.)

The French artist Jean Dubuffet (1901-85) was himself an improvising musician and released a number of recordings, including Musique Phénoménale recorded with fellow artist Asger Jorn (1914-73) and released in 1961 as a boxed set of four 10” LPs. What is interesting in the present context about his approach both as artist and musician is that his principal source of inspiration was the “outsider art” produced by self-taught individuals existing outside the art world, indeed not infrequently outside regular society in mental institutions. He held “to be useless all those types of acquired skill and those gifts (such as we are used to finding in the works of professional painters) whose sole effect seems to me to be that of extinguishing all spontaneity” (quoted in Sansom 2001, p. 33). Improvisation is frequently mentioned in the context of outsider art on account of such artists often using whatever materials are to hand in creating their work, rather than purpose-made art materials with their associated skills and traditions. Does this kind of process have musical implications? It’s easy enough to pick up an instrument one isn’t familiar with, and make some kind of sound on it, but it seems likely that this kind of activity can only remain interesting for a short duration, unless one goes on to invest in it the kind of intense commitment with which an outsider artist might engage with their materials. In fact, that kind of engagement is no different in kind from the dedication of a virtuoso musician. Using “whatever materials are to hand” also has a long pedigree in improvised music, beginning with such manifestations as Keith Rowe’s use of radios to generate “found sounds” as one of the layers in AMM’s “laminar” approach to improvisation.

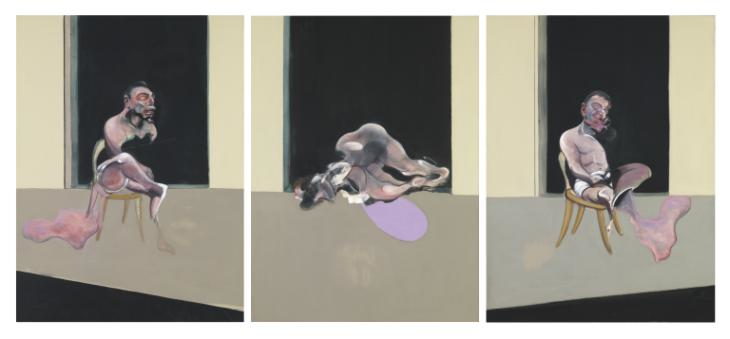

Given that the “input” from Abstract Expressionism is thus both obvious and deep-rooted, I don’t think it’s appropriate to discuss it further in the context of the present study. In my book Music of Possibility I contemplated the relationship between (what I imagine to be) the techniques used by Francis Bacon (1909-92) and my own compositional practice in combining precomposed and spontaneous actions for complementary and/or overlapping structural and poetic purposes, citing:

the way that exquisitely nuanced, sometimes even photorealistic areas on the one hand, and seemingly randomly thrown splashes of paint on the other, not only coexist but are somehow perceptually interchangeable. It’s not always clear at a first or even second glance whether some element of a painting is the result of painstaking and precise brushwork on the one hand, or a rapid and seemingly spontaneous swipe with a sponge on the other. (Barrett 2019, p. 65)

Francis Bacon, Triptych August 1972

This complex interpenetration and confusion between spontaneous and considered activity, and Bacon’s way of using it to capture a moment or an aftermath with an ambiguous and disturbing emotional charge, probably lies outside the range of possibilities the present text is intended to address. I mention it here as an example of a (much) further extension of the kinds of ideas explored in the compositions in this section. Another artist mentioned in Music of Possibility is Andy Goldsworthy (b. 1956), whose work:

clearly blurs the distinction between the “natural” and the “artificial”, in that his interventions into nature, clearly designed from the standpoint of a conception of beauty which could only be human, nevertheless frequently acquire their identity (and their beauty) from the non-human processes which are poised to return the materials to their original state (which itself is always a state of becoming). (Barrett 2019, p.222)

In Goldsworthy’s work, as in much musical improvisation, the place where a work is made defines its material, and the material is then worked on using an incrementally expanding vocabulary of forms – river, spiral, cairn, archway, aperture and so on. But the improvisatory method by which Goldsworthy deploys and expands his knowledge of the natural materials isn’t the end of the process: a spiral string of leaves linked together by thorns unravels and begins its journey down a brook; a nest-like assembly of twigs built on seaside rocks is picked up by the tide and carried out to sea, disintegrating as it goes; other works have much longer or much briefer lives, whose durations are “composed” into them as they come into being, sometimes for no longer than it takes to photograph a handful of dust thrown into the air, while other works might leave traces for many years. These processes of decay and dissolution might be imagined also as musical processes.

Composition 4

Everyone begins by playing short repeated sounds in

synchrony (counted in or conducted or coordinated in some other way) in

a rapid tempo, 240 bpm at least. Change your sound to another short

repeated sound at irregular intervals approximately the length of a long

breath. Within each “breath”, sounds may change slightly in pitch,

dynamic, timbre etc. Once this structure is established, begin to change

your individual tempo slightly. At the same time, start to substitute

silences for one or two of the sounds in each “breath”. Gradually

increase this substitution until each “breath” contains only one or two

sounds, or possibly none. The music ends when everyone is silent.

Possible extension: in each new “breath”, choose a sound you can already

hear or have just heard someone else play.

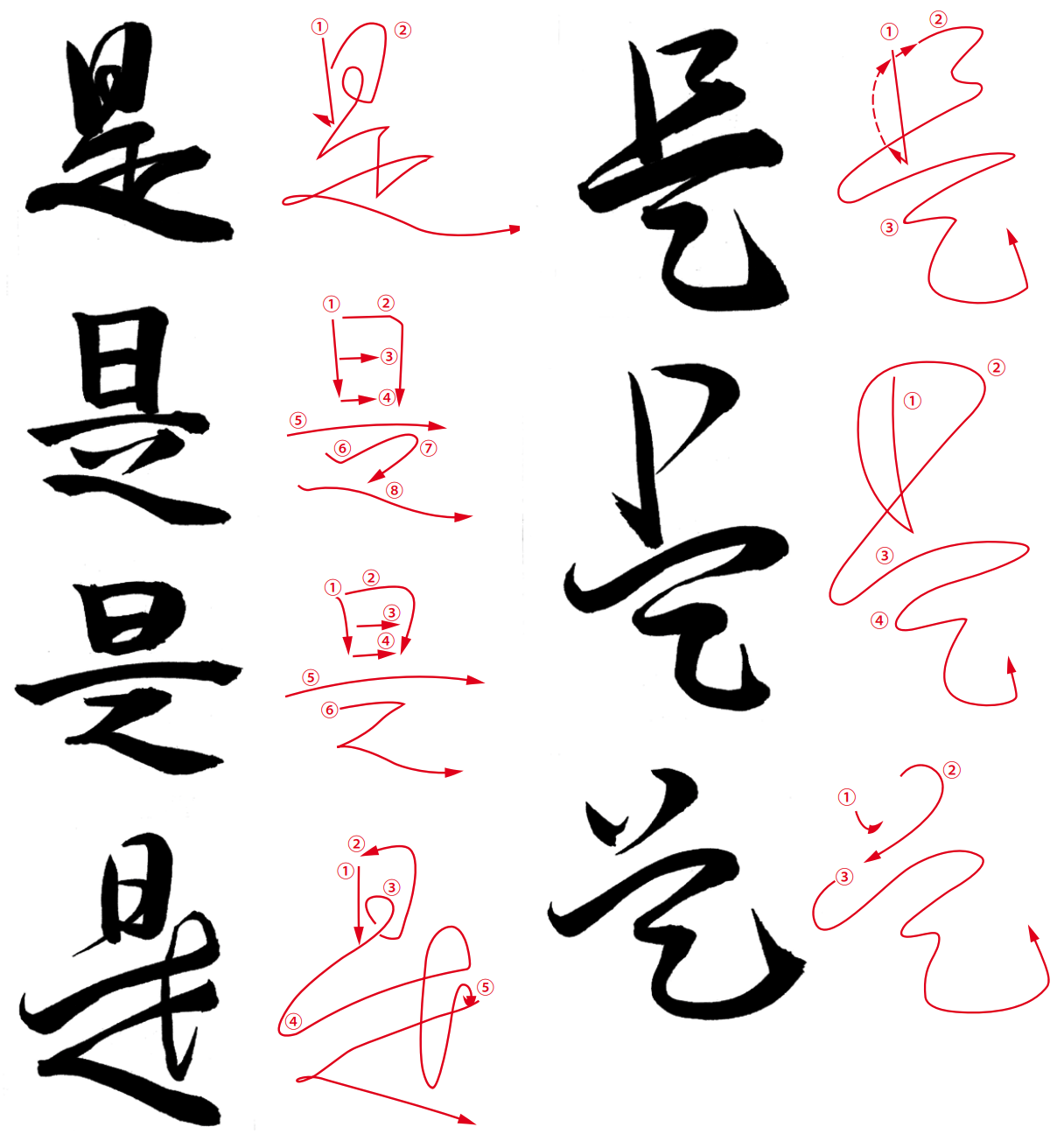

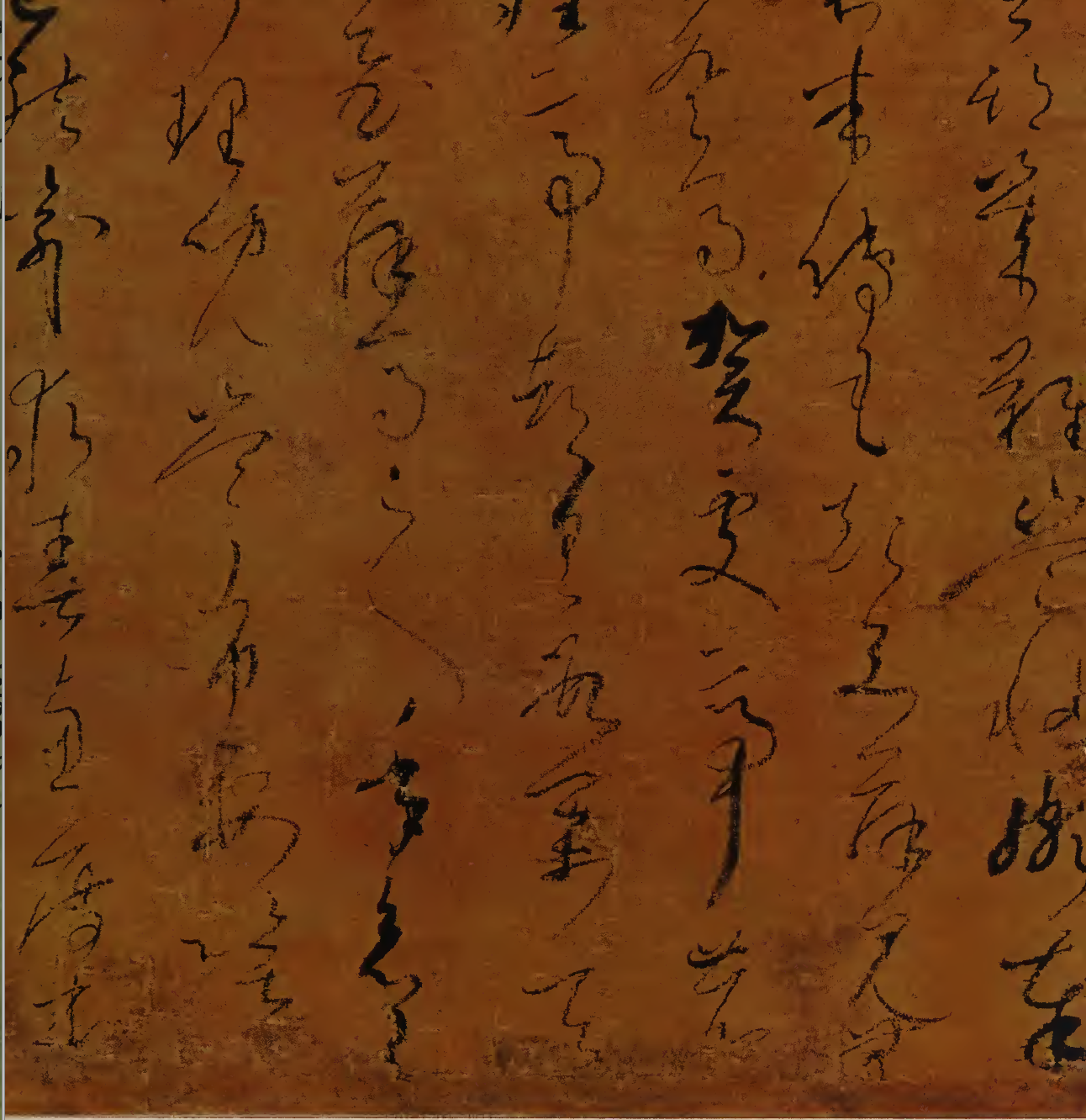

The mention of breath, and indeed the natural forms which Goldsworthy’s work amplifies and stylises, might be considered to lead naturally to a consideration of the art of Japanese calligraphy, which combines graphic and performative aspects in a fascinating way. Even for the viewer who isn’t aware of the meanings of the (originally Chinese) characters used in this kind of work, which goes some way beyond the functionality of writing, perhaps in a similar relation to is as singing might have to speaking. While the execution of its brush-strokes must be done rapidly and without the slightest hesitation, these actions are preceded by intensive preparation both of the materials used and of the calligrapher:

The combination of sumi (black ink) and brush used to create Chinese ideograms is called shodo or “The Way (do) of Writing (sho).” To create sho as an art form requires not only physical preparation but also mental preparation. The sho creator must learn breathing control and how to concentrate energy or ki (chi) in the lower part of the abdomen. (Since ancient times, the martial arts disciplines of Asia have required this same centering of a person’s ki energy in the lower abdomen.) The sho creator, by concentrating and internalizing energy, can then pick up the brush and in a matter of seconds execute an ideogram. (…) In shodo it is considered sacrilege to go back and touch up the work. Any adjustment or touch-up would be apparent, and would interrupt the ki, and therefore the created work wouldn’t be an honest representation of the artist’s energy and personality. (Sato 2013, p. 10)

The emphasis on breath control is as musically suggestive as the illustrated diagrams of movements made with the brush:

[W]hile the brush is in motion you should be aware of your breathing: when you inhale, when you exhale. Usually the sequence is to inhale, hold breathing, move the brush and begin gradually exhaling; finish exhaling when one section of the ideogram is completed. In the art of sho, spirituality and physical activities have to coincide, therefore breathing control is of utmost importance. (Sato 2013, p. 31)

The illustration shows seven variations on the same character (ze). (Sato 2013, p. 58) The diagrams are of course incomplete in that they show only two dimensions, while the third dimension, that of the changing thickness of the stroke, is omitted, although it can easily be observed in the finished characters. A process of improvisation is taking place here at a microtemporal level, so to speak, in the beautiful combination of precision and instability which characterises the physical relationship between calligrapher, brush, ink and paper and which can be traced in its finest details by the viewer.

Composition 5

Begin with a long silence, during which all

participants attempt to prepare themselves by imagining a single complex

motion in sound (bearing in mind the forms of calligraphic characters)

which might last between the duration of a single staccato and a few

seconds. On a signal (with an upbeat or intake of breath) from one of

the participants – an order can be specified so that everyone has a

turn – everyone plays their sound, after which another long silence

begins. Each sound might be different in some or all regards from the

previous one, or a variation on it, or identical to it.

The purpose of this section is of course not to provide an exhaustive survey of even one person’s view of ideas and procedures from the visual arts that might inform musical improvisation in general, and free improvisation in an educational context in particular, but to employ a few examples of how this process might take place, which might act as a starting point for discussing with students how they themselves could use related ideas to inform their own contributions to a workshop or performance preparation.

Calligraphy by Fujiwara Sukemasa (tenth century CE). Nakata 1973, p. 59

section 3: theatre and film

When embarking on the present research, it seemed to me that the theatre, being like music a “time-based” artform and indeed one with long, well-documented and continuing traditions of improvisation, would probably furnish more valuable models for musical improvisation than for example painting. The tradition of opera also, with its endlessly renewed strategies for unifying music and drama, would seem to point in the same direction. This turned out not really to be the case, as will be seen in this section, whose most potentially fruitful aspects might seem to be located in this somewhat unexpected incommensurability, and in the distinct ways in which improvisation is defined and employed in theatre and music.

Antony Frost and Ralph Yarrow (1989, p.3) trace the origins of improvised drama to shamanic “performances”, which is to say many thousands of years before the beginning of recorded history, although a more familiar early manifestation of it is the Italian commedia dell’arte which dates back to the 16th century. While the content and structure of a performance might be improvised, this is on the basis of familiar stock characters whose relationships are practised and rehearsed. The use of improvisation in theatre is in fact largely characterised by spontaneity and fixity occupying distinct stages in the work-process, rather than being interwoven in all of them as is perhaps more characteristic of music (or for that matter painting). Discussion of improvisation in the theatre generally centres on it as part of the process, that is to say part of the preparatory process for something which will eventually take on a more or less fixed form, rather than the whole process. Even so, improvisation in drama is often described in terms which would seem equally to apply to music:

Improvisation is … immediate and organic articulation; not just response, but a paradigm for the way humans reflect (or create) what happens. Where improvisation is most effective, most spontaneous, least “blocked” by taboo, habit or shyness, it comes close to a condition of integration with the environment or context. And consequently (simultaneously) expresses that context in the most appropriate shape, making it recognisable to others, ‘realising’ it as act. In that sense, improvisation may come close to pure ‘creativity’ – or perhaps more accurately to creative organisation, the way in which we respond to and give shape to our world. The process is the same whenever we make a new arrangement of the information we have, and produce a recipe, a theory or a poem. The difference with doing it a l’improviste, or all’improvviso, is that the attention is focused on the precise moment when things take shape. As well as being the most exciting moment, this is also the most risky: what emerges may be miraculous or messy – or a panic retreat into habit or cliché. (Frost and Yarrow 1989, p. 2)

Keith Johnstone (b.1933) produced the influential book Impro: improvisation and the theatre (Johnstone 1979), which, alongside Improvisation for the Theater by Viola Spolin (1906-94) (Spolin 1963), created the vocabulary of ideas and activities which still dominates theatrical improvisation. According to Frost and Yarrow,

Keith Johnstone stresses two narrative skills, free association and reincorporation. … Free association means spontaneous response, ‘going with’ whatever has been offered, by oneself or by one’s collaborators. It means letting one idea generate the next without trying to force it into shape: without trying to make it mean something (it undoubtedly will mean something). It means accepting, too, that part of the meaning (the true ‘content’ of the story) will be the performer’s revelation of him/herself.

Johnstone abandons the notion of content, and concentrates instead on structure – the key to which is reincorporation. When telling a tale, either singly or with others, reincorporation means making use of what has already been introduced. It means coming back to ideas previously established, and then using them in ways that both bind the story together and take it forwards. Free association takes care of invention and development; reincorporation takes care of structure. … Apparent randomness is given sudden illumination by reincorporation. (p. 134-5)

The emphasis on “reincorporation” underlines a theme that runs through writings on improvised theatre. On one hand there’s a certain pressure to incorporate features that seem to simulate the kinds of structure familiar from scripted theatre. Conversely, another idea often met with is that of working with themes, situations or characters suggested by audience members, so as to underline the actors’ virtuoso spontaneity. Both of these features give an impression of an assumption that improvised drama is in some way impoverished relative to scripted drama, and this needs to be addressed firstly by clear structural recapitulation and secondly by giving the performance a sport-like character (sometimes even a competitive one). What is supposedly lacking in the simulation is compensated for by the improvisational skills on display. Free improvisation in music seems to be comparatively untouched by such expectations (although improvising on a given theme has a long history in music, going back at least to 1747 and the story of how J S Bach’s Musical Offering was improvised and then later written down on a theme suggested by Friedrich II when Bach was visiting his palace at Potsdam). Nevertheless, the idea of reincorporation, being something that seldom occurs in improvised music, is something that perhaps could be fruitfully explored.

Composition 6

Each member of the group thinks of a compact and

recognisable musical event, possibly preparing it beforehand, bearing in

mind also that it should be something your fellow players will be able

to “use” in different ways. Play it at or near the beginning of the

improvisation, and now and again thereafter as seems appropriate. When

you aren’t playing it, either be silent or react in some perceptible way

to something you hear (it doesn’t matter whether or not you identify it

as someone else’s “recognisable event”). If you hear the same event from

someone else more than once, respond each time in a different way.

Spolin (1963) places the questions “who, what, where” as central in her manual of improvisational techniques and exercises for actors, which are of limited applicability to music, although again she begins with some considerations which are sufficiently general (or vague?) to be recognisable to most practitioners of improvised music:

Through spontaneity we are re-formed into ourselves. It creates an explosion that for the moment frees us from handed-down frames of reference, memory choked with old facts and information and undigested theories and techniques of other people’s findings. Spontaneity is the moment of personal freedom when we are faced with a reality and see it, explore it and act accordingly. In this reality the bits and pieces of ourselves function as an organic whole. It is the time of discovery, of experiencing, of creative expression. (p. 4)

The acting games described herein, and in other handbooks of improvisational technique, remain close to the kinds of interactions that might commonly occur in realistic scripted drama, or in real-life situations. Tom Salinsky and Deborah Frances-White (2008) ask several times in their Improv Handbook why the kind of improvisation they discuss has barely developed since its beginnings, and perhaps this inbuilt conservatism is one of the reasons.

Music, on the other hand, doesn’t need to relate to real-world situations at all (although it can). While “musicality is a dimension of perfectly ordinary reality” (Cardew 2006, p. 133) it seems to be based on a particular way of listening (which might be mixed with others, for example when there are words or movements), of experiencing sound and time. Theatre in which timing is used in a particularly musical way (in the work of Samuel Beckett for example) is recognisable as such, for example in its use of pauses. (A silence in music is something happening.) Theatre improvisation has evolved many pragmatic principles which flow from assumptions about what a narrative might consist of, that don’t necessarily apply in music. To find ideas and principles from the spoken theatre that could be more valuable in the context of improvised music, it might be necessary to look outside explicitly improvisational approaches to drama. Here for example are three highly suggestive passages from The Empty Space, written in 1968 by the director Peter Brook (b. 1925):

We [Brook and Charles Marowitz at the RSC] set an actor in front of us, asked him to imagine a dramatic situation that did not involve any physical movement, then we all tried to understand what state he was in. Of course, this was impossible, which was the point of the exercise. The next stage was to discover what was the very least he needed before understanding could be reached: was it a sound, a movement, a rhythm—and were these interchangeable—or had each its special strengths and limitations? So we worked by imposing drastic conditions. An actor must communicate an idea—the start must always be a thought or a wish that he has to project—but he has only, say, one finger, one tone of voice, a cry, or the capacity to whistle at his disposal. (Brook 1968, p 57-58)

Slowly we worked towards different wordless languages: we took an event, a fragment of experience and made exercises that turned them into forms that could be shared. We encouraged the actors to see themselves not only as improvisers, lending themselves blindly to their inner impulses, but as artists responsible for searching and selecting amongst form, so that a gesture or a cry becomes like an object that he discovers and even remoulds. We experimented with and came to reject the traditional language of masks and makeups as no longer appropriate. We experimented with silence. We set out to discover the relations between silence and duration: we needed an audience so that we could set a silent actor in front of them to see the varying lengths of attention he could command. Then we experimented with ritual in the sense of repetitive patterns, seeing how it is possible to present more meaning, more swiftly than by a logical unfolding of events. Our aim for each experiment, good or bad, successful or disastrous, was the same: can the invisible be made visible through the performer’s presence? (Brook 1968, p 60)

In everyday life, ‘if’ is a fiction, in the theatre ‘if’ is an experiment.

In everyday life, ‘if’ is an evasion, in the theatre ‘if’ is the truth.

When we are persuaded to believe in this truth, then the theatre and life are one.

(Brook 1968, p 171)

While these ideas don’t address improvisation as their central focus, I would say that they probably have much more of value to say to improvising musicians than many writings that do. Brook is questioning what theatre actually is, which writers on improvised theatre tend to stay clear of. Working on improvised music seems to me to put the practitioner in immediate contact with questions of what music is or could be, with each performance embodying one or more provisional answers. One of the things it could be, perhaps, is a “play” between participants who take on different roles. While divisions of musical labour are quite characteristic of much music in the jazz tradition – soloist, harmonic/textural support, rhythm section – one of the innovations of the free improvisation that grew out of that tradition was that any instrument could fulfil any one or more of these roles at any time, shift between them, and invent new roles arising uniquely from the ongoing musical situation. As I explained in A Year in the Life of the Sonology Electroacoustic Ensemble (Barrett 2020), I often find myself in the role of a “glue” that links other musical layers together, an example of which can I think be clearly heard – in the first half especially – of this trio piece performed in 2016 at the Bimhuis in Amsterdam together with Evan Parker (tenor saxophone) and Michael Vatcher (percussion):

_

Composition 7

Assign one or more members of the group (not

necessarily the obvious ones!) to two or more of the following roles:

melody instrument, harmonic/textural background, rhythm section, so that

around half of the group is thus occupied. This half begins alone. The

other half then explores ways of creating links between these roles. At

a certain point the first half stops playing. Possible extension: roles

could be distributed randomly (for example using cards) and exchanged

during the performance.

Keith Johnstone himself has some suggestive comments for teachers of improvisation:

I began reversing every statement to see if the opposite was also true. This is so much a habit with me that I hardly notice I’m doing it any more. As soon as you put a ‘not’ into an assertion, a whole range of other possibilities opens out—especially in drama, where everything is supposition anyway. When I began teaching, it was very natural for me to reverse everything my own teachers had done. I got my actors to make faces, insult each other, always to leap before they looked, to scream and shout and misbehave in all sorts of ingenious ways. It was like having a whole tradition of improvisation teaching behind me. In a normal education everything is designed to suppress spontaneity, but I wanted to develop it. (Johnstone 1979, p. 16-17)

Many teachers don’t seem to think that manipulating a group is their responsibility at all. If they’re working with a destructive, bored group, they just blame the students for being ‘dull’, or uninterested. It’s essential for the teacher to blame himself if the group aren’t in a good state. (Johnstone 1979, p. 40)

I say to an actress, ‘Make up a story.’ She looks desperate, and says, ‘I can’t think of one.’

‘Any story,’ I say. ‘Make up a silly one.’

‘I can’t,’ she despairs.

‘Suppose I think of one and you guess what it is.’

At once she relaxes, and it’s obvious how very tense she was.

‘I’ve thought of one,’ I say, but I’ll only answer “Yes”, “No”, or “Maybe”:

She likes this idea and agrees, having no idea that I’m planning to say ‘Yes’ to any question that ends in a vowel, ‘No’ to any question that ends in a consonant, and ‘Maybe’ to any question that ends with the letter ‘Y’. (…)We used to play this game at parties, and people who claim to be unimaginative would think up the most astounding stories, so long as they remained convinced that they weren’t responsible for them. (Johnstone 1979, p 194, 198)

At the centre of his thinking, and something that has an obvious application to musical improvisation, is the idea of an “offer” and its being “accepted” or “blocked”:

I call anything that an actor does an ‘offer’. Each offer can either be accepted, or blocked. If you yawn, your partner can yawn too, and therefore accept your offer. A block is anything that prevents the action from developing, or that wipes out your partner’s premise. (Johnstone 1979, p 164)

Good improvisers seem telepathic; everything looks prearranged. This is because they accept all offers made—which is something no “normal” person would do. Also they may accept offers which weren’t really intended. I tell my actors never to think up an offer, but instead to assume that one has already been made. (Johnstone 1979, p 169)

This principle, known sometimes as the “yes, and” technique, has been successfully transplanted from its origins in improvised drama to use in such situations as business meetings (the idea of status transactions has a central place in Johnstone’s thinking), which at least to me suggests that it should be treated with a certain suspicion! Ultimately, though, a musical improvisation isn’t a conversation, since it generally focuses on simultaneity rather than succession, which leads to the question of whether it’s possible to imagine a way of approaching it that begins from the linearity of a conversation but “tilts” it from the horizontal towards the vertical, so that what was initially successive becomes simultaneous (or what was “melodic” becomes “harmonic”). When I think of “accepting” in Johnstone’s sense I think of letting what I hear effect some change in my musicality and then to express that change in sound. “Blocking” would be to ignore what I hear – although this is always a possibility, made perhaps less problematic in musical improvisation than in the theatre by, once again, the possibility of simultaneity.

Composition 8

Assign a number to each member of the group. The music

begins with each member in numerical order making a brief contribution

which (apart from the first!) continues perceptibly from the previous

one. When the second “round” begins the contributions begin to overlap

with one another, and this overlapping process continues until each

“round” consists of almost simultaneous entries while still bearing in

mind the principle of each contribution “answering” the previous one.

Then the whole process could begin again. Possible extension: use two

sequences of numbers rather than one, so that two instances of the

aforementioned process are taking place concurrently.

In so far as theatre depends on spoken language, it can only ever involve “idiomatic” improvisation, to use Derek Bailey’s formulation – “non-idiomatic” improvisation in Bailey’s sense would only be possible by abandoning the necessity of staying within the boundaries of a vocabulary already familiar to the audience. (Such a possibility was indeed explored for a while by Peter Brook’s International Centre for Theatre Research in the 1970s, particularly in the 1971 piece Orghast, performed using the pseudo-archaic language of that name invented by the poet Ted Hughes – see Smith 1973.) Film, on the other hand, isn’t necessarily constrained in the same way; indeed in the earlier decades of its history film was unable to include spoken language, and the possibility of silence (or of music) is still always present. Like theatre, improvisation in film tends to occur as part of a process rather than the whole process, although an improvisatory approach is possible at various stages in production, leading here not to a repeatable “text” but to an immutably recorded result, thus something more akin to a music recording than to a theatre script. As Maria Viera observes in the context of the work of director John Cassavetes (1929-89):

Filmmaking is a particularly fluid process susceptible to re-thinking and re-working throughout the entire production process. A director will rewrite lines in rehearsal and improvise on the set for reasons as varied as weather changes, equipment failure, or actors’ moods. Intentions which have been in place since the beginning of production are routinely abandoned in the editing room. These are the creative conditions of filmmaking. No matter how meticulously planned, circumstances arise which force a director to improvise on the set or in the editing room. (Viera 1990, p. 35)

Nevertheless, “Cassavetes’ work is not, in fact, improvised; but improvisation is what his work is about.” (Viera 1990, p. 35) What does this mean? It seems to be connected with the way that Cassavetes’ films explore a complexity of rival positions without seeming to exercise a single authorial attitude, a centred point of view, thus exemplifying the decentred aspect of group improvisation. Another example of improvisatory ideas finding their way into the film-making process is the work of Jean-Luc Godard (b. 1930) – "by freeing the montage from the constraints of the match cut, it was suddenly possible [for him] to to improvise during the montage." (Mouëllic 2013, p. 51) Actual free improvisation in film-making would extend to every participant in the production and every stage from rehearsal and location-scouting to the finished cut. But, on the other hand, the role of a director like Cassavetes or Godard might provide a model of an altered role for the composer of improvisation-related music – beginning from a “shooting script” allowing creative input from other participants, “accepting their offer” rather than suggesting or demanding changes, then overseeing the production process – a form of writing that doesn’t aim to limit or restrain but rather to encourage emergence and revelation, which Gilles Mouëllic likens to the kind of compositorial input that occurs in jazz (Mouëllic 2013, p. 28) but which of course doesn’t need to be limited to any particular style. I had the unexpected opportunity in the summer of 2020 to explore the potential of just such a compositional production process.

In late April of 2020, in the midst of the Covid lockdown in Belgrade (curfew between 5pm and 5am and all weekend), I was contacted by the Boston-based singer Tyler Bouque with an invitation to take part in the Alinéa Ensemble’s “Everything but the Kitchen Sink” project, combining interviews with diverse composers and video performances by the members of the ensemble of selected solo compositions.

link to Alinéa Ensemble’s Youtube channel

One of my principal motivations as a creative musician is for my work to embody a response to its social and political conditions, not in an anecdotal way but by turning those conditions into opportunities for creative renewal, and for the opening of new possibilities for how the music might further evolve and expand the perceptions and consciousness of its participants, among which its listeners should be counted as central. I use the formulation “creative musician” rather than “composer” in order not to place real or imagined limits on the activity, taking a cue in this regard, as in others, from the example of Anthony Braxton, with all that this implies. In the pandemic of 2020, then, I had been exploring ways in which the music I’m making can respond to changes in its situation, and turn these changes in a creative direction, rather than hunkering down and composing the same music I was composing previously and waiting until the crisis has passed, or whatever.

I began by working on binaural versions of various multichannel fixed media electronic pieces, in order that listeners might get some kind of impression of their spatiality in the absence of concerts with 8-channel sound systems. When heard on headphones, these versions of Vermilion Sands, disquiet and luminous have a more open and transparent sound than the conventional stereo mixdowns I had previously prepared, even if three-dimensional spatial definition isn’t as convincing as is often claimed for this kind of software. (The freely downloadable Sennheiser AMBEO Orbit plugin was used.) On the other hand, I began to imagine what the possibilities might be for a music specifically composed for this format, treating its idiosyncrasies as characteristics of that “instrument” rather than comparing them unfavourably to another one.

Milana Zarić and I assembled a duo recital for harps and electronics on video at the end of May and beginning of June, of which the final element is a fixed media piece (entitled sphinx) which we composed together and which was so to speak native to the binaural domain. This idea wouldn’t have come into existence under other circumstances, and it’s not a compromise to them but, as mentioned previously, a response that opens up an unanticipated new way of doing things. The process began by recording some improvisational harp material, some freely played and some concentrating on specific sounds and techniques. This was then categorised, transformed in various ways and composed into a structure whose components were characterised by different configurations within the virtual binaural space.

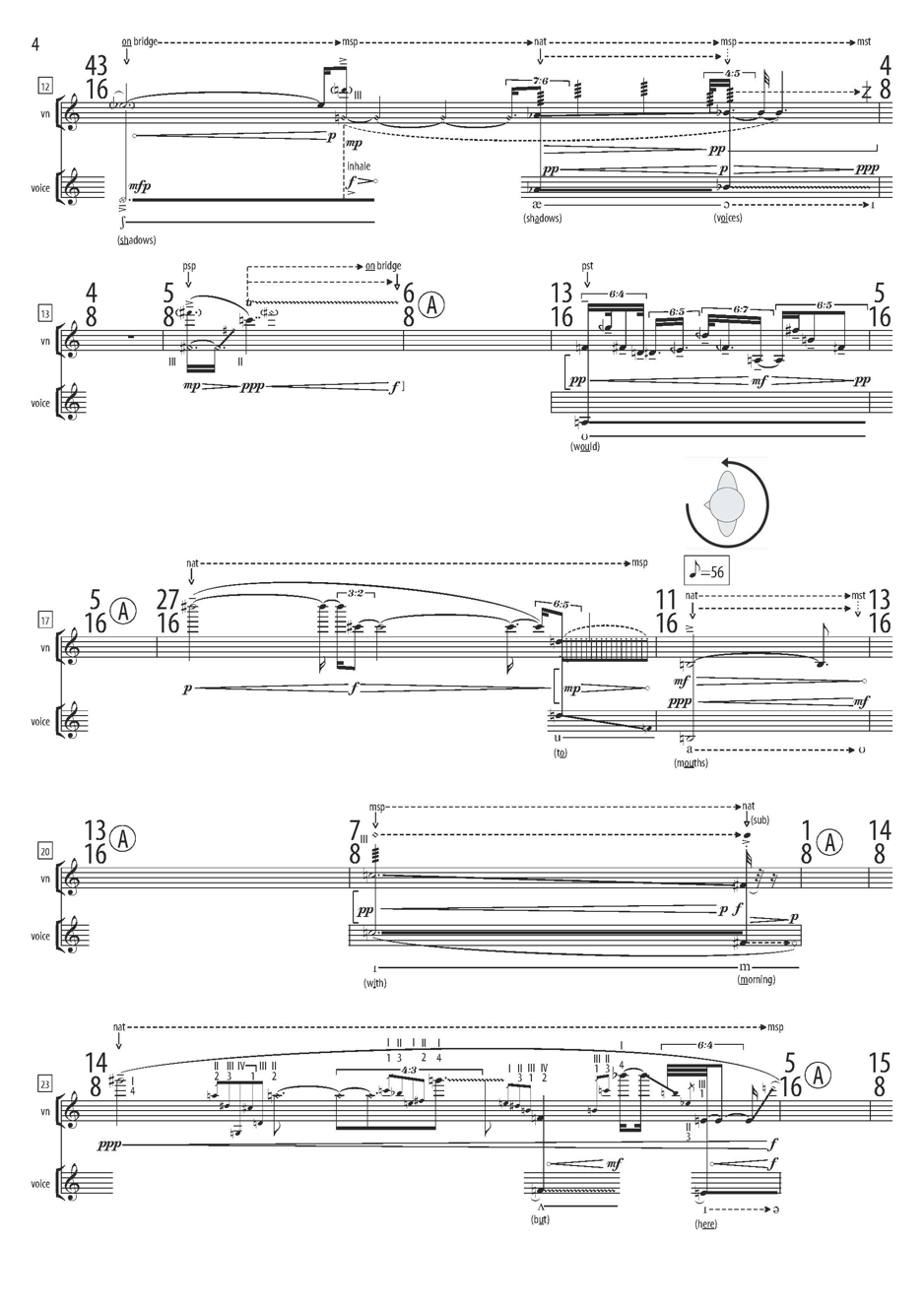

While thinking about how sphinx was to be composed, I responded to the Alinéa invitation by suggesting that, instead of a performance of a solo piece, I would contribute an entirely new composition. This would consist of partially notated material for six members of the ensemble (voice, violin, cello, contrabass, piano and percussion), which they would record individually and send to me, and on the basis of which a binaural fixed media composition would be made for their virtual concert series.

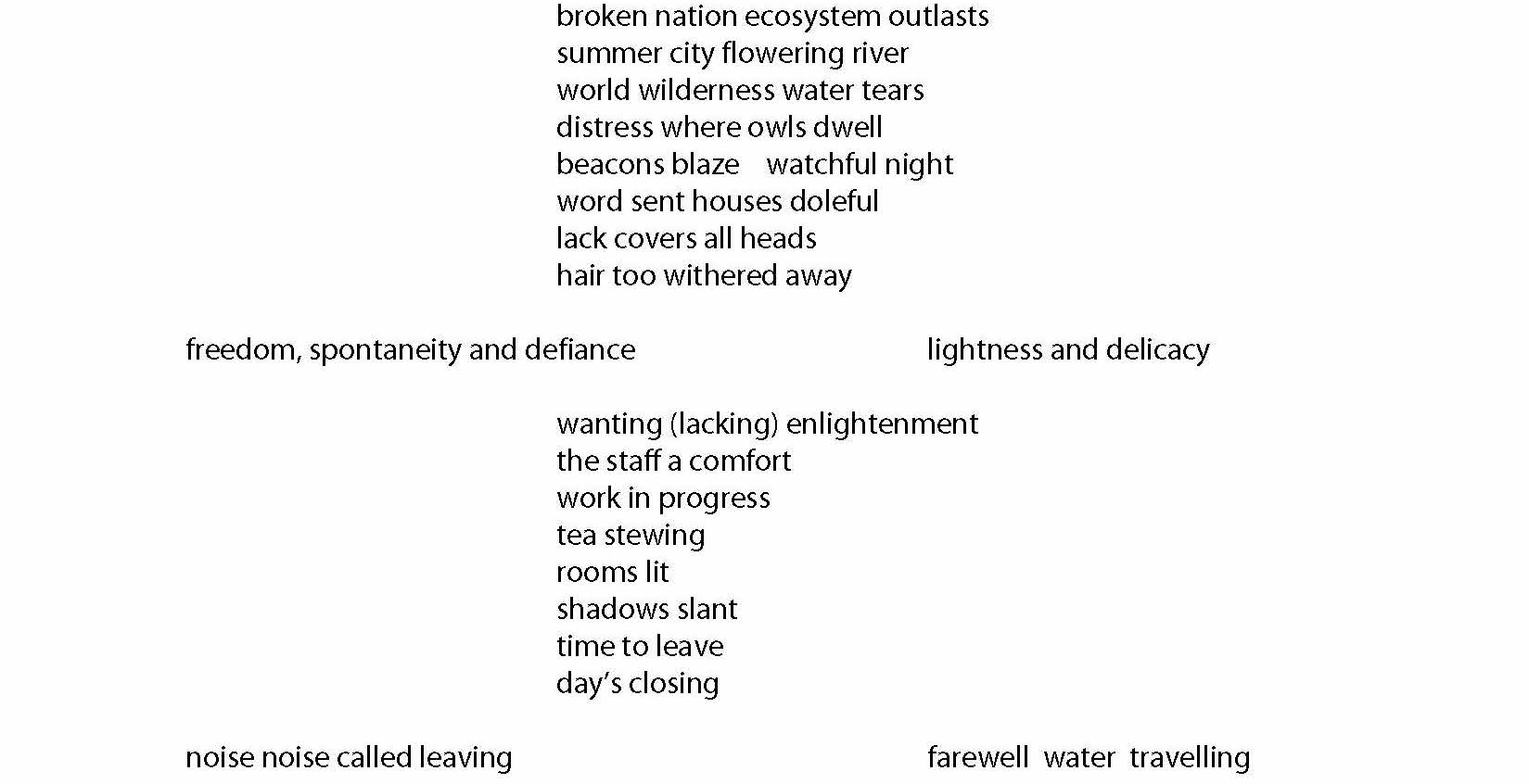

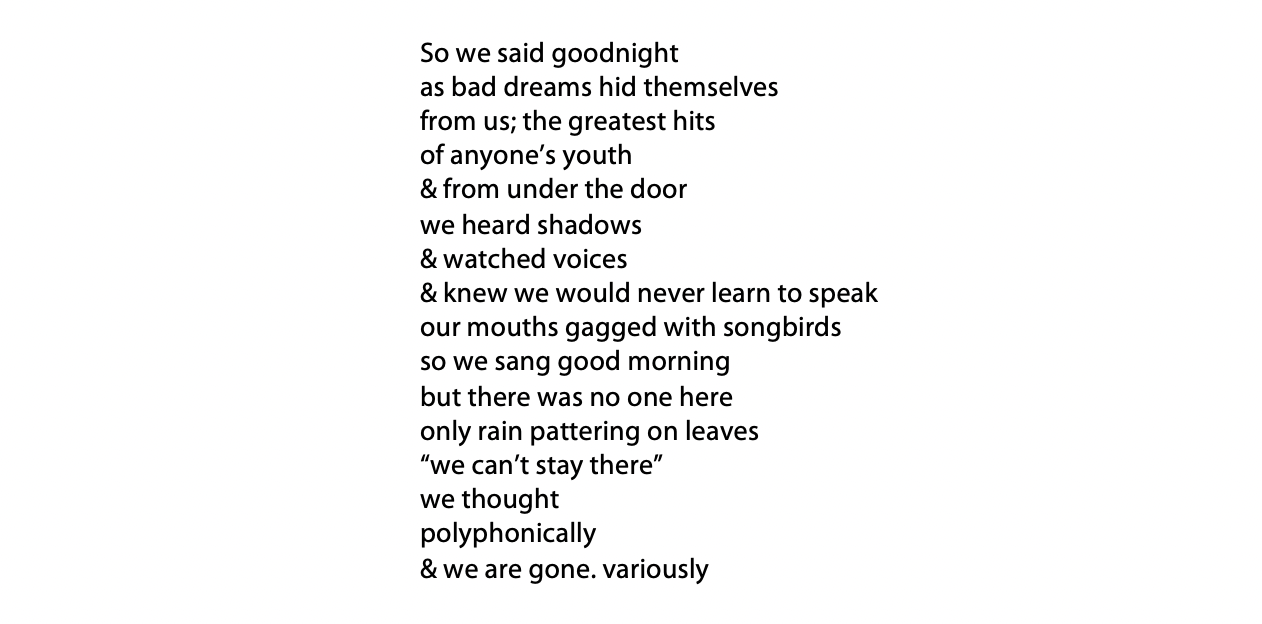

The text used in the piece consists of eight poems from the collection eye-blink by the English poet Harry Gilonis (Gilonis 2010), which for a couple of years already I’d been considering as the basis for a musical composition. The 64 eight-line poems in the book are distant rereadings (as opposed to translations) of poems by eight Chinese poets of the T’ang period: their origins and their actuality are constantly interweaving, mirroring and shadowing and sometimes distorting one another. (This is the same body of work on which Gustav Mahler drew in Das Lied von der Erde, again using translations and indeed eventually additions of his own.) I take the title to refer to the way that a written Chinese character gives rise to a concept or image “all at once” rather than the latter being revealed gradually through a linear sentence as in Western languages, a feature which is reflected in a musical structure consisting of a sequence of sixteen “sound-images”. Six of the poems appear in the music as complete but brief “songs”, while the other two occur simultaneously in longer, more static moments, one line at a time, in between the others. The format of the text here reflects the order and simultaneity in the music; the eight poems aren’t in this order in the book and are all formatted as one eight-line poem per page.

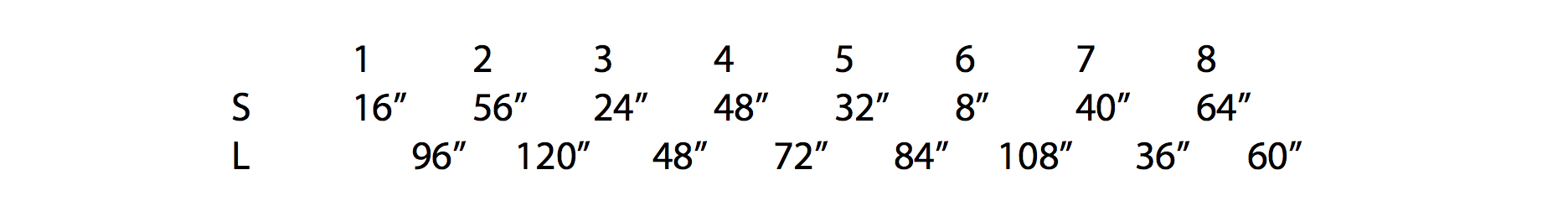

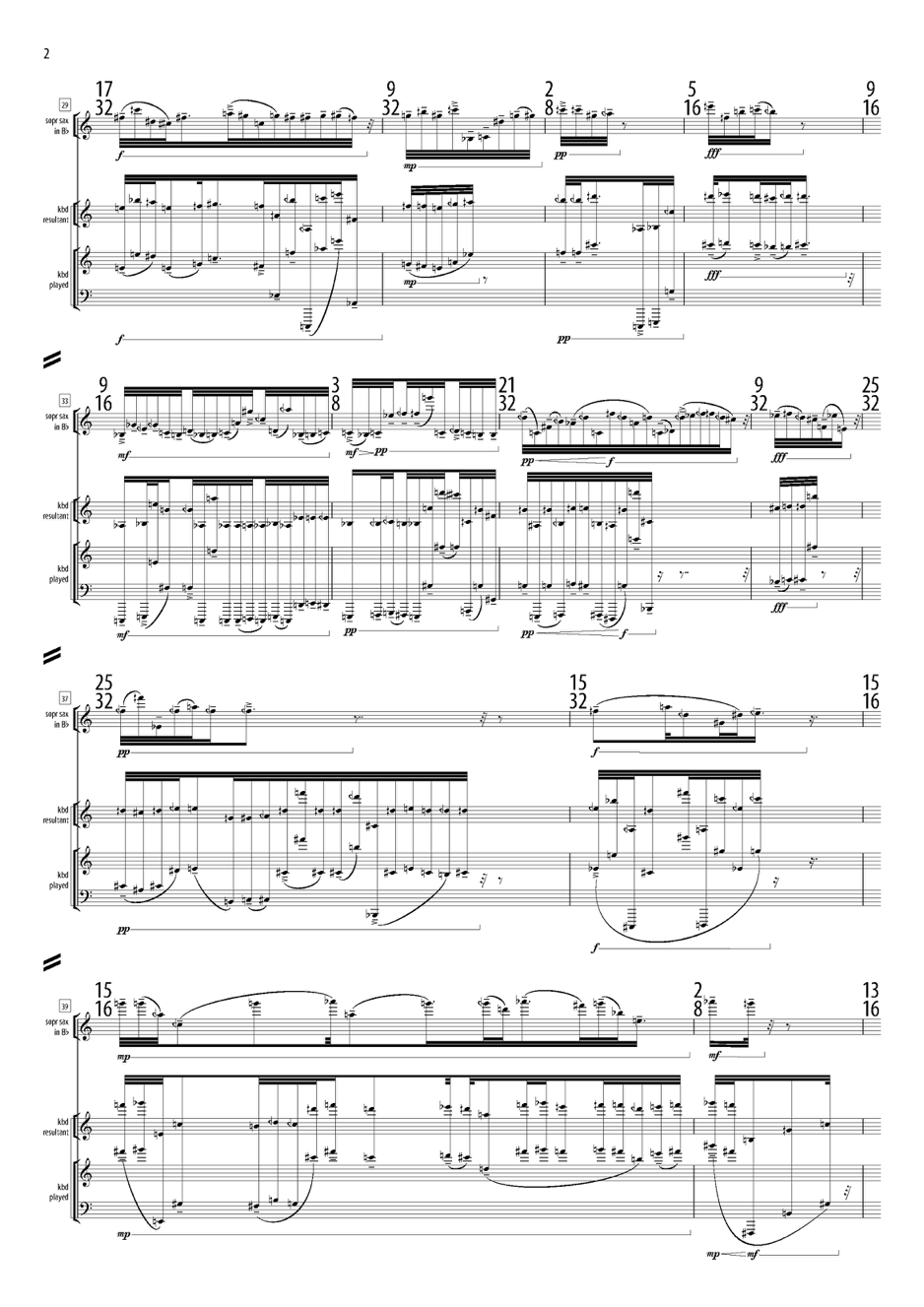

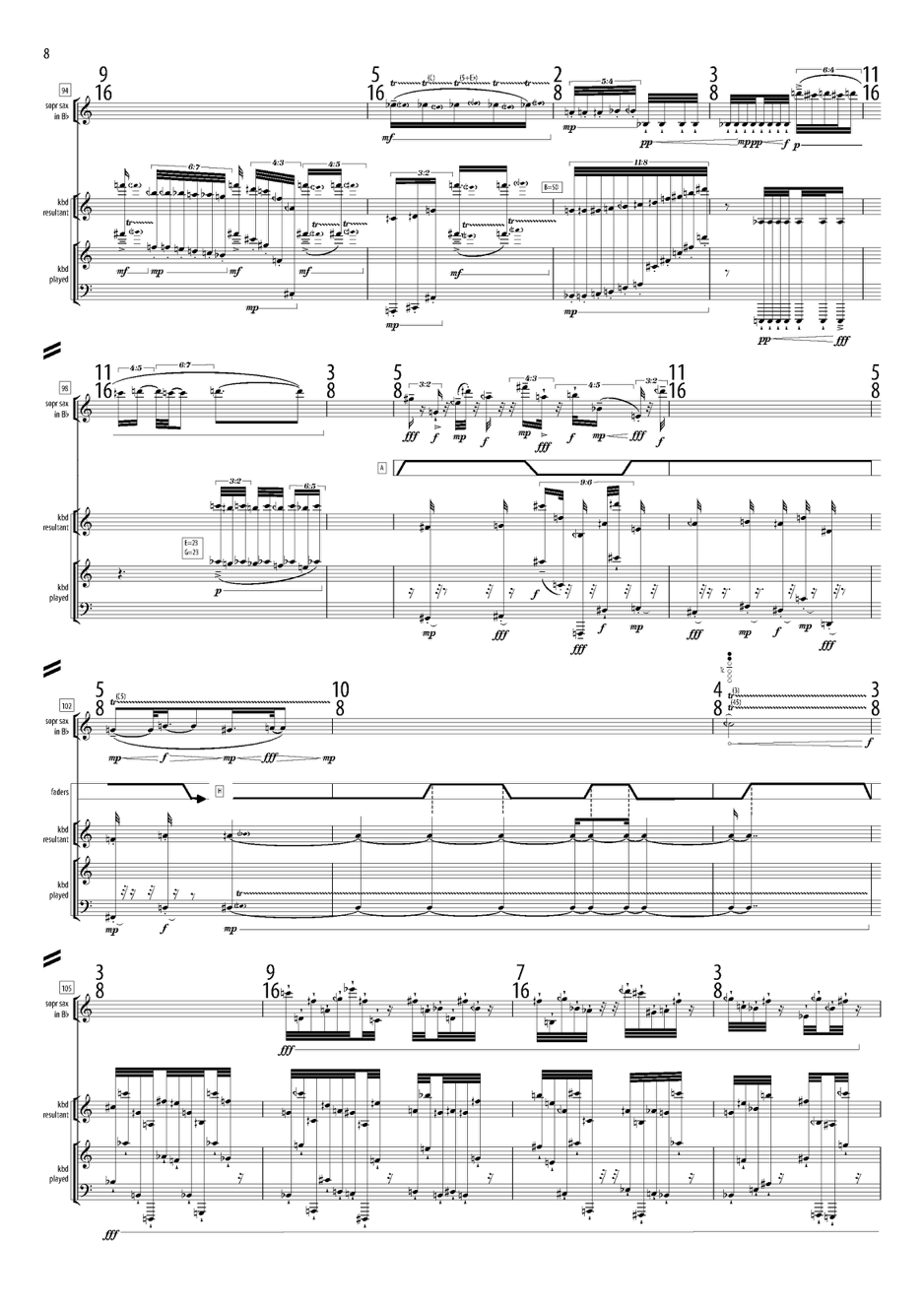

This division into longer/static and shorter/active structural elements was the first and most influential decision in the composition process (and in fact reflects an exploration of this kind of relationship that characterises much of my recent work). The structural framework for the composition was then filled out by assigning a duration to each of the sixteen elements (including two sections in the “short” sequence with no text – the sixteen-second introductory sound before the voices enter with the first “long” section, and, later on, an eight-second silence), and a harmonic aggregate to each of the static ones. The “short” and “long” sections are heretofore referred to as S1-8 and L1-8. The time-structure of the piece is:

I reserved the possibility of altering the overall time-structure according to the dictates of the eventual sonic materials, although in fact all of the original durational proportions (see below) are retained precisely, with the exception of L8, which is extended by 132" (the next duration in the duration-series used for the L sections!) so that the original total duration of 15’12" becomes 17’24" (augmented by a further few seconds of silence in the final soundfile). The non-vocal material of L8 was the first part of the piece to be composed, since it consists entirely of electronic sounds and could be completed while I was waiting for the vocal and instrumental recordings to be made, and it seemed appropriate to extend it with a long fade during which its 8 layers (pitches) drop out one by one until only the lowest and highest sounds are left.

The eight harmonic aggregates are as follows:

which may be described as 1+2+3+4+5+6+7+8 pitches adding to 36, forming three twelve-tone series in terms of pitch-classes, expanding gradually in register, aggregates 3 and 6 with intervals getting larger from top to bottom (approximating to the odd-numbered partials of a harmonic series in aggregate 6), aggregates 4 and 7 with intervals getting larger from bottom to top, aggregates 5 and 8 symmetrical. Aggregates 4 and 5, and 7 and 8, have one and two pitches in common respectively, and these pitches sound through the linking “short” sections.

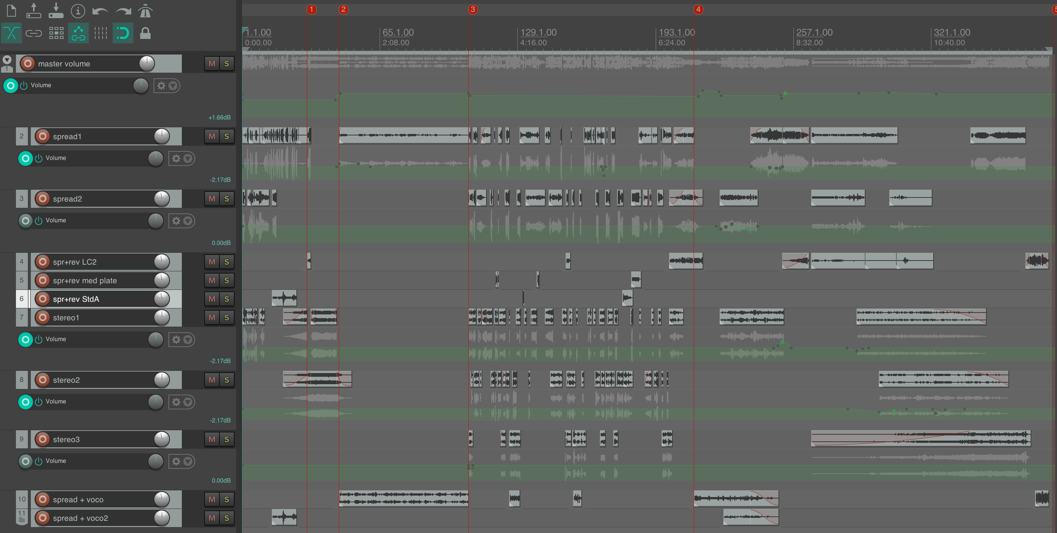

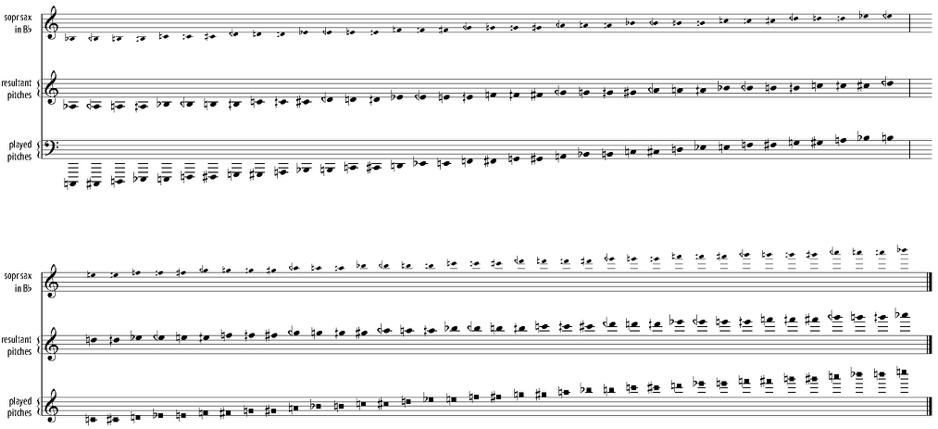

The score of sections L1-8 was then completed by assigning pitches of the aggregates to voice and instruments in different ways, ranging from almost free improvisation to precise pitches and rhythms, and placing an emphasis also on timbral character and variation. The binaural spatialisation involved defining 24 discrete virtual positions – 8 at ear level, 8 raised by 45 degrees and 8 lowered by 45 degrees – and assigning tracks to them, generally in some kind of symmetrical formation. In the L sections the two voices always appear at front left and right positions (and sometimes others as well, as in L6 where there are 8 voices altogether, 4 left and 4 right), while in the S sections the single voice may be at front centre or might be distributed line by line through the virtual space. The solution of using 24 virtual positions was arrived at after making sketch versions of two sections and deciding that work could be speeded up by creating an empty template DAW session with tracks correctly positioned, which could then be used as the starting point for the binaural mix of each section.

In some cases the recorded materials of L1-7 were taken over with very little alteration into the composition. The sustained sounds of L1, for example, were treated only by introducing very slow microtonal fluctuations in pitch, in order to enhance their spatial separation. On the other hand, other materials were subjected to much more processing. The A-C# alternations in all the instrumental parts of L2 were first laid end to end and then the resulting soundfile decomposed into grains sampled at random positions, so that the result is a dense web of rapidly varying articulations, speeds, timbres, spatial positions and filter parameters.

The material for sections S2, 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8 was organised quite differently. (S1 consists only of a gradual fade-in of the sound materials of L1, and S6 is silent.) The vocal material for S2, 4 and 8 was precisely notated, while that for S3, 5 and 7 consisted only of the text with the direction to improvise on it, some suggestions of the vocal techniques that might be used, and the request that two different recordings be made. (In each case the vocal part in the actual piece was made by editing between the two takes.) There was no specific instrumental material for these sections, only directions for two recordings (labelled B1 and B2 in the score respectively): the first consisting of a 36-note series based on the pitch-classes of the eight harmonic aggregates, transposed differently for each instrument, to be played as a repeating loop, each time leaving out about half of the notes and replacing them with freely chosen sounds (a technique used in several of my codex scores); and the second requesting six minutes or more of free improvisation which might or might not refer to any of the notated materials used elsewhere in the piece. The purpose of B1 was to generate a sequence of mostly brief sounds exploring the entire pitch and timbral range of each instrument, and of B2 to create an opening to any and all unexpected possibilities – for example the repeated muted-piano sounds which are a central feature of S6. If the ensemble had been preparing the B1 material together (especially if I were there to provide guidance and/or clarification), the players would no doubt have come to a consensus about how it should sound; since they hadn’t, each player brought a different and distinctive approach, from the isolated staccati of the cello to the melodic sound-sequences of the violin. This of course once more provided an opportunity rather than a problem! In most of the S sections the instruments are multiplied on one another to varying degrees – for example S6 is “scored” for 5 violins, 3 cellos, contrabass, 4 pianos and percussion – while in S4 the voice is only “accompanied” by fragmented versions of itself, and in S8 the (heavily filtered) voice sounds through a crossfade between two alternating piano chords held over from L7 and a widely separated F#-C dyad (also present in the piano chords) on synthetic sounds which continues into L8.

The working process (excluding sketches and dead ends, and with various exceptions) had the following form: (1) all recorded parts were individually “mastered” (using EQ, compression and limiting), and the stereo recordings of voice, violin and cello mixed down to mono (the bass part was already mono and the piano and percussion parts were left in stereo owing to the nature of the instruments), to give maximum flexibility in further processing and mixing. (2) The necessary materials for each section were extracted and mixed/edited together, often with a stage of processing outside the DAW at some point before or during the mix, and also often with processing within the DAW, for example pitch-shifting and/or reverb. (3) The resulting tracks were extracted and imported into the aforementioned 24-channel binaural template session and then mixed to stereo. Sometimes I would go back to the previous stage to make revisions that weren’t convenient to do in this session, for example changing the temporal relationships between sounds within a section. (4) The stereo sections were assembled in a further session at their assigned points in the time structure, first the L sections and then the S sections. In most cases I would then go back to stage (3) and produce a revised version with changed balances and/or other alterations which would then once more be inserted into this final session. (5) Finally, the balance between sections was adjusted within the final stereo session until a definitive mix was produced.

It might be said that this piece is consistent with my previous work in exploring contradictions not by reconciling them but by putting them into a dynamic relationship, neither balanced nor unbalanced – like spontaneity and simultaneity, or acoustic and electronic sounds, or abstract and referential ideas… if what I’m doing has an individual aspect this might be what it is.

For example: I thought for many years about Stravinsky’s comment that music isn’t able to express anything outside itself, (Stravinsky 1975, p. 53) and, while I do have sympathy for this idea, I wanted to be able to find a way of thinking musically where both this and its opposite are true and perceptible. This is a way of thinking that really only finds its means of expression in the music, and doesn’t lend itself to being reduced to words, but one way of hinting at it is to say that Stravinsky is quite right but on the other hand we can imagine that there is nothing outside music, that it’s overlapping or coextensive or interconnected with many other things. I don’t want to draw any kind of borderline between what is music and what isn’t.