Barbara Engh’s essay ‘Adorno and the Sirens’ examines the entrenchment of female voice within a corporeal form. Engh responds to Theodor Adorno’s essay ‘The Curves of the Needle’, published in 1928 in the avant-garde journal Musikblatter des Anbruch. Adorno’s original comments were upon the recording of the female voice, some three decades after the invention of the phonograph. He stated:

‘Male voices can be reproduced better than female voices. The female voice easily sounds shrill – but not because the gramophone is incapable of conveying high tones, as is demonstrated by its adequate reproduction of the flute. Rather, in order to become unfettered, the female voice requires the physical appearance of the body that carries it. But it is just this body that the gramophone eliminates, thereby giving every female voice a sound that is needy and incomplete.’ (Adorno, 1928 in Engh, 1994:128).

Let us pause on that last word. Incomplete.

Despite the loaded term ‘shrill’, Engh stresses that Adorno ‘does not invoke’ arguments regarding the acoustics or pitch of women’s voices. Rather, she summarizes: ‘Women technically have access to the realm of artistic transcendence, “to unfetteredness,” as long as they keep a human voice together with a human body as they sing.’ (1994:129). Indeed, Adorno goes on to state that:

I see a (backward-facing prism)

(gnicaf-drawkcab msirp)

before me,

an infinity mirror, a lineage of women,

(or rather, pictures of them)

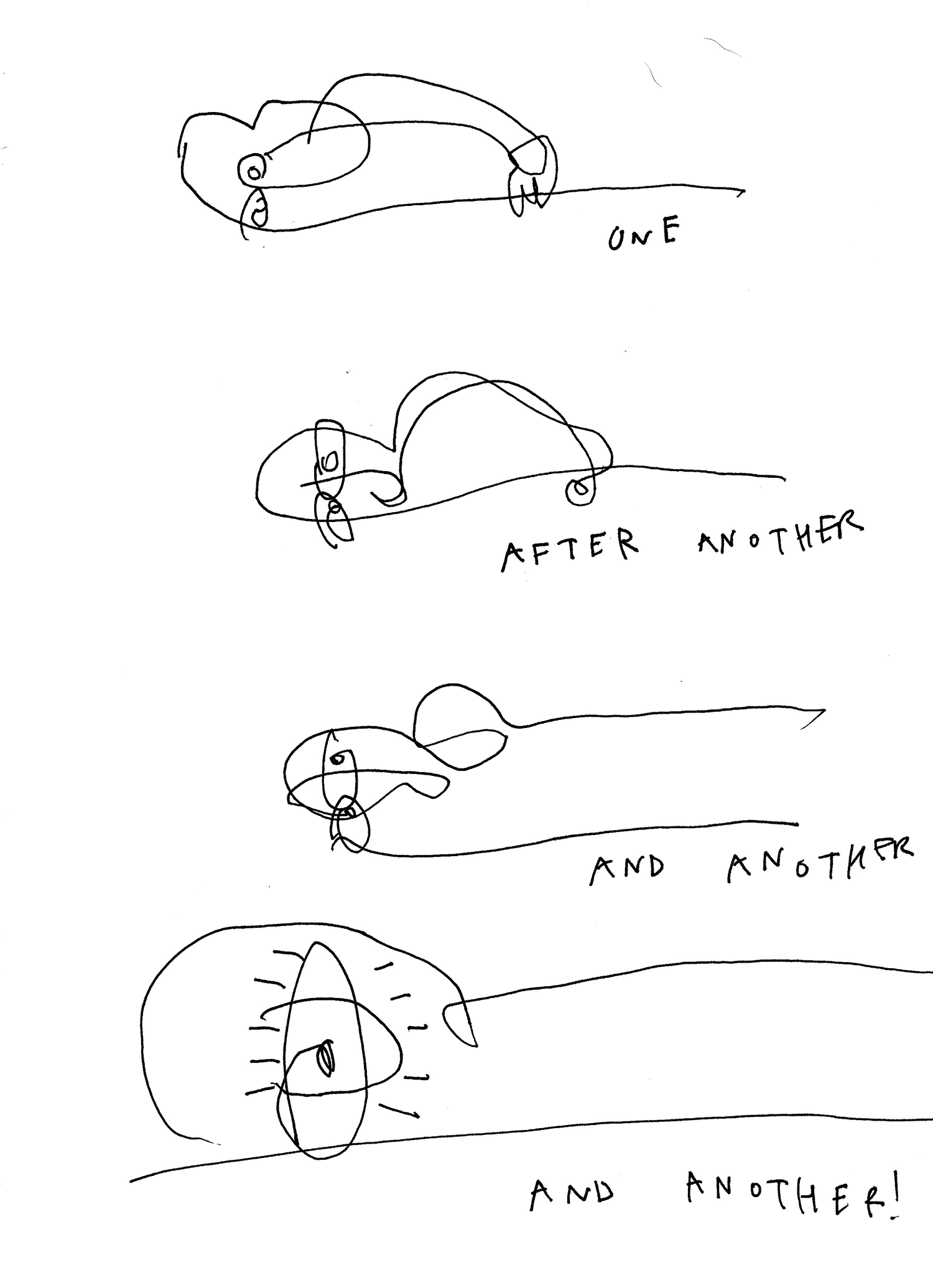

one image after another

splits dizzyingly,

tremulously,

shattered.

primed for the eye, with

motives charted on body-maps;

contorted arms and breasts (of course)

and open mouths

and more eyes

on the

objects that fascinate, fascinate, fascinate

suspended

(How to shift this?)

for whatever you do, you will always do it wrong.

They (they, they, they, all of they, and that includes YOU, and ME) will always locate you (/me); assign a body to; sketch their own assumptions onto your matter. It is a sticky game.

‘wherever sound is separated from the body – as with instruments – or wherever it requires the body as complement – as is the case with the female voice – gramophonic reproduction becomes problematic.’ (ibid)

This alleged co-dependence of the female voice and the corporeal form succinctly analogises the problematic that line fights against within my work. The problematic in question is that the presence of the feminine voice, or experience, has historically been assigned to a body to look at. A body experiencing the experience. As Engh states: ‘In any woman’s disembodied voice one sees immediately a reflection of one’s own self-desiring glance – or not. One bestows upon oneself a self-benediction, and guarantees self-presence from afar, even as, by authorizing that supervision, unwittingly loses oneself.’ (1994:131).

Hypothetically, if I asked you, now, to draw what you felt; to draw your experience, to speak without drawing the body, what forms would emerge? Almost a decade ago, I first encountered that sense of incompleteness – and back then, felt frightened.