1. Full article available here although it may be behind a paywall: Josh Spero, “Listen to the sounds of lockdown,” Financial Times, March 31, 2020,

https://www.ft.com/content/3c578d9e-725f-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca.

2. Caetlin Benson-Allott, “Going Gaga for Glitch: Digital Failure @nd Feminist Spectacle in Twenty-F1rst Century Music Video,” in The Oxford Handbook of Sound and Image in Digital Media, ed. Carol Vernallis, Amy Herzog, and John Richardson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 127.

"Anime Deep Cuts" by Josh Spear. Performed by Bastard Assignments, 17/4/2020. Version shown with the video score in the centre.

4. Full article available here although it may be behind a paywall: Josh Spero, “Listen to the sounds of lockdown,” Financial Times, March 31, 2020,

https://www.ft.com/content/3c578d9e-725f-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca.

5.“Subracttttttttt,” ThingNY, accessed 8 January 2021, http://www.thingny.com/subtracttttttttt.html.

8. Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massumi (London: Continuum, 2014), 6.

6. Joshua Minsoo Kim, “Incorporating in-game sounds and actions into their compositions, Lil' Jürg Frey find a new way to play Animal Crossing: New Horizons,” The Wire, no. 438 (2020): 84.

,__ ^_.||:_dOWn_DeePCUts_'LOCk[ANIMÉ.InVENTION] :||,•__\-‘ -

- Études for the beginning of an online practice

For more than two years we enjoyed this routine of meeting at least every two months for a week at a time, and living in the same space, cooking and eating together. This was during our residency at Snape Maltings in UK. We each had work to make with the group as either solos or ensemble pieces, and which was usually in preparation for a show.

Then suddenly this routine was broken and the idea of being able to meet in person, to devise and rehearse every few months, as was our process, vanished. Our planned gigs were cancelled in Vilnius and Cambridge for example, although unlike most orchestras and venues, this was not a disaster for us; it was an opportunity to change, to adapt. We declared that we ought to keep working somehow, to try and keep together as a group when real-life contact was not possible.

At first, we tried Google Hangouts, improvising, using instruments and objects and our voices. It was so unsatisfying for me that I didn’t look forward to the meetings. The sound I was making didn’t seem to be heard in the maelstrom of the others, as if the medium weren’t fit for purpose. As I saw it, our medium was now the internet and no longer just sound. It may be said that our medium hasn’t been sound for a while, instead it has become the arena of performance, the stage itself maybe.

We persevered, we continued by transitioning to using Zoom. It seemed to deal with us better than hangouts or maybe, week by week, our understanding of the medium increased. In Zoom we quickly explored the “background” possibilities, where you customise your presence for your co-callers. And we played. We met and played every week once or more, for at least an hour, exploring ideas or improvisation, trying over and over.

We shared our Lockdown Jams on social media and then garnered the attention of Josh Spero, who featured us in the Financial Times. His article “Sounds of Lockdown” was published in late March 2020.1

It was after doing a lot with the group, after feeling like we had a practice, of being and playing together, and flowing with them that I had an idea, a compositional concept for how to use this situation. It would push me to go back to using a score again, albeit with a post-internet twist.

I was excited about the first session I led with the group; the task provided just enough of a challenge for us whilst being something we could all do. It was also very clear what the goal was: we were to copy a video in unison.

I chose two videos: a makeup tutorial and a viral hit from 2012 that features a Justin Bieber song. We were to only copy the movement we saw, not make any sound ourselves as I wanted to keep the original audio from the videos we were copying. After realising that the lag on Zoom might make synchronisation difficult, I thought to use the world clock so that we could each start our videos playing at the same time by each referring to the same time source. Both of these videos make demands on our individual personal space, our objects around us, and our bodies, freshly illuminating these things.

The notion of the Internet as our medium is so clear in these videos by virtue of the glitch, particularly clear in my square. From time to time my face or pose freezes and we call this a “glitch”, a surplus of working live on the internet where after an image freezes because the internet cannot deliver the image fast enough, we then see the image skip forward in an attempt to re-synchronise itself with the audio and the rest of the conversation. Caetlin Benson-Allott points out that Glitschig means slippery in German and writes “[t]he Glitch is a disease of time, a pause and a potentiality.”2

In the following examples, I call the videos that we are copying—that are not seen by the audience—the score. Whilst the videos move and seem highly active objects, they are dead like a sheet of notated music; they do not change and they are unresponsive. Like a written score where the ink won’t fall off the page, the videos can be given to someone else and interpreted with the right instructions or code.

Not unlike Richard Dedominici’s Redux Project, the material he uses exists on the internet and in many people’s consciousness already.3 Whilst Dedominici is perhaps parodying a genre or filmmaking technique, our work foregrounds how each of us interprets the material and handles it freshly. An interesting remnant of this work is that we glimpse into the intimacies of each other’s homes, turning domestic spaces into work and performance spaces that become a storied part of our work together as we continue meeting, week on week.

If my first experiments were about unison then my next iteration would be about creating counterpoint through canon. This choice, though unconscious, is significant if we consider that I experienced having to come up with a new method for working with the group at a distance, in a new situation that was purely online. It forced me back to what I knew about: music and composing music. So, it’s no surprise that my instinctual response to planning how to structure my ideas is to make present my musical training and apply musical ideas to this quite unmusical material.

I took what worked: our ability to imitate. I created something more complex in organisation. I made four video parts from a variety of sources on YouTube, sources ranging from ASMR videos, Dance Dance Revolution, to tutorials on kissing and video editing.

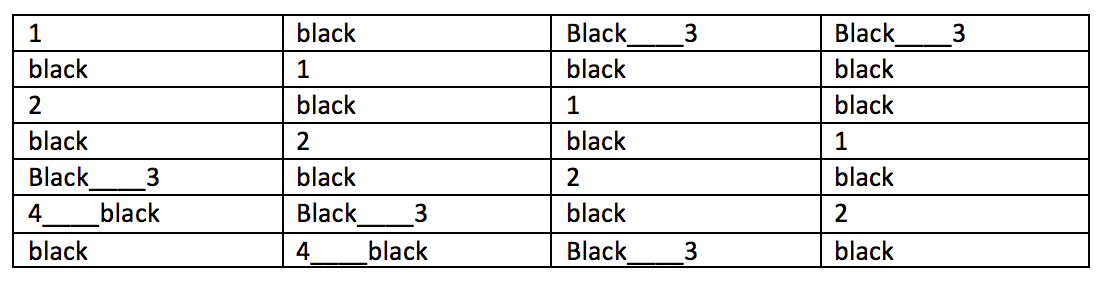

My idea for a canon would be the idea to use a ‘black’ screen, simply achieved by covering the camera with a hand. Sonically, I tried to make sections 1 and 2 dovetail, so that the focus was on the first part of section 2 before switching to the second half of section 2—both these sections happening simultaneously of course. In practice this didn't work because of how Zoom privileges continuity of sound and will only allow one "speaker" at a time. This was a useful experiment in this regard. Below is the structure for my canon idea with each column being one person and each row representing ten seconds. Each part enters ten seconds after the preceding one. It should be said that charts like these are not the score yet; the videos I made for each of us to copy are the scores.

Two days after this, on 17th April 2020, we tried again. I had made a two-part invention with a focus on investigating what might happen rather than knowing what would emerge. Having made the canon explicitly to be imitated precisely, I wanted to open the next version out—by that I mean allowing my colleagues to interpret what they saw. I also chose images and .GIFs that are almost impossible to actually imitate. The clips were varied with different types of “shot”, some up close, some more scenic, some looping awkwardly, and all demanded that my colleagues consider and divide their personal spaces and bodies in creative ways. Again, the two-part invention is a musical form—a short composition with two-part counterpoint—and a way for me to organise my thoughts when dealing with four performers sharing a screen.

Here is how I organised the material. My only idea was that whilst one part was “watching,” the other part did something that was more “active” physically and, like the canon, that the changes from one state to the other be clear. It is apparent in the result that there is a top line and a bottom line; what Tim and I are doing is the same whilst Ed and Caitlin are paired in their own activity, separate from us. The order that the participants join the call is important in this regard. We realised that the person who is recording the session is positioned on the top right of the gallery view, the next person is to their left, and the rest follow on counter-clockwise in the order they entered. This information became useful throughout the entire Lockdown Jams period.

Having not liked how Zoom handles sound, I decided to only have audio from one part whilst the other is silent. In the previous experiments, the sound was either live or dropped in after in the edit. This meant that the part that Tim and I were copying was the only one with sound but Zoom was recording that sound from both of our laptops whilst relaying and recording sound from the whole group, as if we were in conversation. This was to explore what happens: would it make the audio more consistent through having multiple sources? Would interesting artefacts come into being? Would it somehow confuse Zoom? Or would we hear both versions of the same piece of music, phased ever so slightly?

In reality, all those things happened; the sonic quality is complex. Amidst Zoom’s predetermined behaviour to seek out and isolate the human voice, the loss of fidelity, and the feeding back of the same music between laptops, a bizarre, almost organic sonic texture emerges from the original dreamy source. I chose Stan Getz’ “I Remember When” for no other reason than I had heard it the night before and knew that it would create a suitable montage effect. Similarly, this was very useful knowledge for the Lockdown Jams project.

I think the whole group found the two-part invention enjoyable owing to its looseness whilst maintaining clarity; its concreteness and openness to interpretation simultaneously. That I was successfully inviting the group’s genius in, activating my co-performers was important to me on reflection and I felt that this was the beginning of something new for my practice.

This looseness in performance and emphasis on the visual was exciting and both things that I had been preoccupied with for some time, pre-lockdown. Was I so eager to return to normal again? Whilst I was still in fact doing much of the decision-making, leading the sessions, bringing the material, I was successfully activating my colleagues and giving them great freedom to be creative through understanding what they could do, and what task would be appropriate. I use the word co-performers and it feels significant because in some way, we are all creating collectively, live.

The video below shows our conversation around rehearsing “two-part anime invention.” It is interesting to see that I am rarely leading the rehearsal, and it is often Tim or Ed who are declaring what we will do next. For example, it was Tim’s decision to rehearse in pairs whilst the other pair watches. In the same way, everybody feels able to offer feedback to everybody else. It feels like we are all beginning the exploration of the piece, of the process together as equals and enjoying it.

Next I made a fugue, another musical structure with increased complexity. A fugue is not unlike a canon in that the melody, once heard the first time is heard in the next voice and so on, creating a counterpoint to itself. I would assign a hand gesture to the notes of J. S. Bach’s “Fugue in C minor BWV 847.” Then I would create videos of myself for us to copy, this time a different one for each person. I needed to create eight or so hand gestures for the notes of the octave with occasional accidentals—that is, notes not in the key of C minor but rather in its relative keys of G minor, for example—and I had ideas for whole phrases that would operate outside of this scale system, that would represent melodic motifs rather than single pitches.

I had decided that there wasn’t any space for my colleagues to have input on the fugue; I simply needed to translate pitches into movement and it would be simpler to do it my way and on my own. In retrospect, I see that it would have been possible to, in a sense, build on the work we had already done using movement and space to imitate video, in order to achieve what I wanted to achieve. This would have allowed for the rich subjectivity found in “Anime Deep Cuts.”

It would also have made sense to do this in light of what I already know about group devising and what a large portion of this article is about. If I had asked the group to create their own choreography, to devise their own gestures or to freely interpret visual material that they were seeing using their hands, greater fluency might have been achieved; the movement might have looked even better. I knew all this but chose to regress to the familiar role of composer whereby I decided upon and created all the materials, as well as deciding how to use them.

What surprised me was when Ed had a strong idea for how we, as a group ought to create the audio, the music, for this particular étude. The group as a whole agreed to pursue Ed’s more or less chance operation, whereby we each recorded a fairly static layer of sound on an instrument and stacked them in the edit. With a light touch and having predetermined which sonic register we each would inhabit, we did this quickly. Then it was left to Ed to actually edit the final video and add the audio. It is surprising that whilst I had decided that the fugue wasn’t to be a collaborative effort, it turned out to be just that. The video below shows this conversation.

From here we continued working in this way. Each of us in the group came to the meetings with ideas, and contributed to the ideas of others, favouring doing over too much discussion. Whilst this clearly generates a new kind of work, we were beginning to think how to meld the process into our previous trajectory, how to potentially create work for concerts and festivals that had been postponed or will need to be reoriented to digital delivery.

Whilst the opera houses and orchestras continue to beam out live streams and pre-recorded concerts and performances as if little has changed, we adapt. In the Financial Times, my colleague Edward Henderson is quoted: “[a]nother job is to ask what if that (opera houses and orchestras) all went away? What’s great about being an experimental musician and composer is that that’s your starting point anyway. We’re trained for it, we’re ready.”4 What Ed means here is that we were always outside and free to experiment with what we had, with whatever was around.

As I mentioned earlier, this looser feeling within the work that we have found through exploration is ours and in some way I am in no rush to return to pre-Covid times. It has been our challenge to demonstrate what and how art can continue to be made.

Though it felt like it at the time, we were not alone on our quest to simply continue meeting and working as a group. Other groups notably “ThingNY” and “Lil’ Jürg Frey” seized the opportunity to explore the new mediums and performance arenas for creating music that only the Internet could offer. On their 50-minute video work premiered in April 2020, ThingNy write: “SUBTRACTTTTTTTTT is a series of Etudes, Songs and Scenes, developed in isolation, and crafted for a quarantine culture, intended to toy with the abilities, shortfalls, and comical inconsistencies of bandwidth broadcast."5 ThingNy are made up of six composer-performers who collectively create and perform theatrically-charged experimental music.

“Lil’ Jürg Frey” is a group of artists who took to “Animal Crossing: New Horizons” on the “Nintendo Switch.” On this platform they could design rooms and use avatars to operate virtual furniture and appliances live, with the sound design offering an exciting new palette: “Bahto tells me that scheduled rehearsals…[occurred] many times a week and lasting two to three hours. ‘It felt like being in a legit band,’ laughs Bell. You can tell: while the game’s cute graphics and the performances’ overall premise may feel gimmicky at first, the meticulous consideration for rhythm, sonic qualities and spirited experimentation are undeniable upon viewing and very much in the lineage of Fluxus.”6

Kim continues his analysis: “The pieces here feel even more meticulously planned, and their more methodical nature hints that they might well have been realisations of scores. One room contains rows of toasters played in particular series, the sound of toast flying up occasionally offset by the low hum of microwaves.”7

The slipperiness of the internet and the rough and ready nature of our rehearsal spaces bring about a new process. Our rehearsal space is also our performance space and Zoom is at once our instrument and meeting place. We slip and slide between the creating time and performance time and rehearsal time whilst shuttling between spaces as well.

All this is a performance as exposition of exploration, exploration of many things but especially space and medium. It offers a way out of the composer-performer continuum that I am so interested in moving along but am simultaneously trapped by. It has not escaped me that in the examples presented, I am still holding onto control, holding onto the roles of composer and performer. In a way, the activity of doing research requires that I am able to always define who is doing what and when, without asking my collaborators how they identify in these periods.

It could be that there is no composer exactly but instead a multiplicity of performers and collaborators who meet in slippery time and slide between exploring, rehearsing, playing, and performing. If these different times are slippery, are glitchy, then so are the roles. It follows that perhaps this then is a new form, a true internet form I can work more towards, more explorative than formal, and always slippery. From the video of our conversation, I hope it is clear that my process, for example, flows along time continuums and spaces as well as through Tim, Caitlin, and Edward. I use them and we use each other leading me to describe Bastard Assignments as a multiplicity.8 If one of us were to disappear suddenly from the group then we would need to adapt, but their voice would not disappear from my mind. Treating each other as a resource, we are able to contribute to and disrupt one another and this leads me to describe the group’s structure as rhizomatic.

This would explain my feeling about the fugue étude: the result is quite uninteresting because my colleagues are not activated, not creating, not using their space and not slipping.

Since the time of writing, we have successfully secured funding from Arts Council England to continue not only working in this way together but also commissioning guests to create Lockdown Jams with and for us in our online workspace. This has included more work with Zoom and other platforms as well as video-based work to explore the limits and possibilities, and implement our knowledge of the medium thus far.

For these reasons “Anime Deep Cuts” is a successful étude from my perspective. An étude here meaning an exploration, making an attempt at something within limits. It is important to iterate that each of these études was ostensibly an experiment with the medium of Zoom, exploring how we might perform when using it. I also learned that they were really attempts at creating in a new way, with medium, form, and technique being intermingled and conjoined.

Our discussion during rehearsal usually focused on parameters like characterisation, post-production, mirroring, use of space, and feedback. As these discussions continued and became sedimented parts of the rehearsals, our individual characters also emerged, each with distinct areas of concern. Caitlin was often preoccupied with getting things right, organising browser windows, and starting the video scores at the correct time. Tim suggested ways that we might rehearse and sometimes ideas for how the piece could be, or how it could relate to sound. Ed often voiced the difficulty of the work or spoke about the mood of the group.

This video shows us at the end of “Bieber Baby” and our conversation. It is clear how enjoyable the task was due to the silliness of it as well as the flow state that it put the group into. Tim also contributes an idea relating to the sonic quality of the final piece, which is demonstrative of the group's collective process, and acts as a snapshot of my experience of this exploratory period working with the group.