Peer reviewed journal - published through Research Catalogue, NMH portal

Multiphonics for Stringed Instruments: Performance Practice and Research Practice

Ellen Fallowfield

CONTENTS

Introduction

Practice-oriented research

Instrumental technique

Opportunity

Cello multiphonics

Bibliography

Introduction

back to top

In this exposition, I describe my work on string multiphonics and, in particular, the research that fed into the production of a practical resource, Cello MApp, a smartphone app for cello harmonics and multiphonics, and of a related Special Issue publication that I edited which brought together state-of-the-art work in multiphonics from string players and composers. In addition to discussing the research practice and performance practice behind my work, I shall use this exposition to point to unresolved questions, each with its own pertinent musical and technical consequences, which constitute the seeds of further work that I hope will find its way into practice. For the purposes of accurately describing my working process in performance research, and because it rings true with my experience as a performer-researcher, I shall consider performance practice and research practice as overlapping entities. First, I will contextualise this and then I will describe my methods and results in more detail.

Practice-oriented research

back to top

In my approach, performance research falls within the category of ‘practice-oriented’ or ‘use-inspired’ scientific research, whereby the practical and/or theoretical motivations that initiate research, or determine the ‘leads’ to be followed, then cycle between practice and theory in an iterative process. The intended consequence of this iteration is that both the practical results and the research processes themselves should be modified, and made more relevant, through their interaction. In other words, in this model, research feeds and shapes practice, but is also led by it. This ideal model describes a lively research environment, and one which is prioritised in certain elements of the ‘impact’ criteria for applied research stipulated by research councils. Moreover, it opens the field for interdisciplinary research, since the requirements of practitioners are rarely narrow enough to be confined to a single discipline; in the case of music performance research, this could take in composition, physics/acoustics, psychology, physiology, education, etc. Nonetheless, the structures for undertaking such research in music performance need to be put into place, and I shall describe my process of doing this below.

The practice-oriented model outlined above may be regarded as being in accord with the music-as-performance movement, namely, the move away from a text-based, analysis-led approach that starts with a ‘finished product’ i.e., a musical score (described by Nicholas Cook as ‘the authoritarian prescriptiveness of the analysis-to-performance approach’[1]) and towards performer-led strategies for making and exploring music. An important aspect that has developed from this movement is the valuing of the musical creativity manifested on the part of the performer and the enhanced understanding of the creative collaborative practices that operate between performers and composers (see, for example, work undertaken by the Research Centre for Music as Creative Practice[2], and related publications, especially by Rink et al.[3], and Clarke et al.[4]). The impact of this is seen in the development of performer-led approaches to understanding and refining musical instrument practice and rehearsal. The confining of musicians to the mere status of ‘test subjects’ in psychological studies in musical instrument practice is being rapidly replaced by an interdisciplinary, use-inspired approach, whereby performers, psychologists, and educators jointly formulate research questions, comment on evaluation and intervention methods and test outcomes and practical resources. Examples include contributions to training and evaluating ‘musical excellence’ at the Royal College of Music/Imperial College London’s Centre for Performance Science[5] (see, e.g., contributions by Williamon[6] and Clark and Williamon[7]) and an initiative at the Norwegian Academy of Music where instrumental teachers and students develop, deliver and assess interventions to improve musical instrument practice[8].

Instrumental technique

back to top

From the perspective of musical instrument practice and, specifically, of instrumental technique, a parallel can be drawn between the text-based culture problematised by the music-as-performance movement described above, and a similarly prescriptive maestro-led culture of instrumental excellence. The material results of this maestro-led approach are treatises that describe how aspirational performers should acquire and perfect their instrumental technique. The significance of these texts should, of course, not be undervalued; they constitute some of the most important resources for historically-informed practitioners (e.g. the mid-18th century contributions by Quantz, L. Mozart, C.P.E. Bach[9]) and, alongside etudes and exercises (often also written by maestri), have facilitated the incorporation of critical developments in the history of technique into practice (one example being cello thumb position[10]). Historically, the development of technique and the provision of material (such as etudes) with which to practise technique were connected because performers were often trained as composers, thus avoiding a tension that arises in the modern problematic, as described below. However, the role and the relevance of such materials has changed since the mid-20th century. This can be attributed to various reasons. The diversity of compositional styles present by this time led to a comparably diverse expansion of technical possibilities and demands. Moreover, the subversion of traditional technique itself became a compositional device, acquiring a creative relevance in its own right. This can be seen, for example, in the radicalism of John Cage, the theatricality and comedy of Mauricio Kagel, the compositional structure of Helmut Lachenmann and the intricate virtuosity of Brian Ferneyhough and Iannis Xenakis, the latter of whom apparently described his solo cello work Nomos Alpha as 13 minutes of music “for cello…But it shouldn’t sound like a cello”[11] (translated by author). Furthermore, the terms ‘contemporary’ or ‘extended’ entered the discourse, applied as adjectives denoting special sub-categories of technique, and have been used with arguably both positive and negative intentions and with mixed consequences. A critical consequence, which I identify as the ‘catalogue problem’, is the tendency to create lists of extended techniques without an adequate connection to sound[12] [13].

These factors have served to separate the idea of ‘modern’ technique from that of standardised, ‘classical’ technique. This, in turn, has led to the phenomenon of it being possible for a performance practice treatise written by a modern ‘maestro’ on performing music in the 21st century to exclude any music that was actually composed in the 21^st^ century. Although this sounds contradictory, it is made more or less sustainable by the fact that the ways to have a career as a performer have also diversified, and specialisations in the music of a particular time period, or in a specific instrumental formation, are common. In addition, developments in instrument making and engineering (e.g., the steel piano frame, trumpet valves, the torte bow) that impacted practice both musically and technically (i.e. in terms of loudness, tempo, intonation, slurs, etc.), and which levelled off in the 20th century, have been taken up by specialists, particularly in early and contemporary music (e.g., 3D-printed wind instruments[14], the contrabass clarinet[15], the microtonal oboe[16], etc.).

The shifting ground described above is having an impact. Performers have established new techniques, such as the likely improvisatory origins of woodwind and string multiphonics described below, and performer agency is seen in the growing number of resources that aim to assimilate techniques into practice, especially in the form of blogs and webpages, including my own Cello Map[17] and other popular resources (see Appendix). A new literature has also emerged, that of ‘handbooks’ for contemporary instrumental technique, which, in aiming to appeal equally to performers and composers (and often written by joint composer-performer teams) fall somewhere between orchestration guides and technical treatises. Major contributions to this genre include two series: Bärenreiter, The Techniques of …Playing, and University of California/Scarecrow/Roman and Littlefield Press, New Instrumentation (I provide a comprehensive chronological list in a forthcoming publication[18], see also Appendix).

On one hand, this is a rich environment in which established norms are dissolving and the creative agency of the performer is driving both research and practical outputs. However, despite the existence of some excellent resources, there are weaknesses in this burgeoning literature. I believe the issues may be summarised as those concerning research practice, those relating to performance practice, and those arising at the interface of these. The sometimes confused and unnavigable structure of handbooks, with technical aspects not being broken down into coherent sub-categories, exposes a lack of research strategy and of clear research goals (blogs and webpages at least have the advantage of a search function to improve navigation). Often, there is little evidence of the iterative process of refinement through cyclical feedback between theory and practice having taken place. Moreover, the lack of bibliographic referencing against similar resources, especially those offering similar data but for different instruments, shows that expectations in terms of academic rigour from both authors and publishers are low. This has resulted in a rather static research path, in the course of which resources have rarely used, built upon or improved previous literature. Compounding this, there is a heavy weighting of the illustrative musical examples in favour of the authors’ experiences and, more generally, a reliance upon notation as the medium for conveying such examples – a tendency which seems not to have absorbed the ideological progress made by the music-as-performance movement. Original etude material is often lacking (a notable exception is Svoboda and Roth, who commissioned five etudes to accompany their contribution[19]). Even rarer is material especially written by performers themselves (here, an exception is Garth Knox’s Viola Spaces and Violin Spaces[20]). This can mean that instrumentalists lack musical material with which to develop the specific techniques newly-presented to them in thesis form.

To be able to incorporate state-of-the art research into performance practice, it is necessary to approach the choice of media for research outputs more flexibly. For example, it can be of immense value to supplement often expensive written textbooks with something that presents practical outcomes in a condensed way, in a format that can be brought to a practice room, i.e., simply, balanced on a music stand (a smartphone, tablet, sheet music) and on a platform that is open-access or at least inexpensive. Below, I describe the opportunity for improving this output.

Opportunity

back to top

There is much opportunity to develop research and performance practice. Doctoral qualifications in music practice, which, having become well established in English-speaking countries and Scandinavia, are now extending throughout Europe, sustain an ecosystem of quality research through the formation of hubs consisting of postgraduate, postdoctoral and professorial researchers, operating in research centres, including those mentioned above, within conservatoires and the European ‘arts universities’. The establishing of music practice as research, and implications of this in terms of appealing to funding bodies, particularly regarding musicians’ preparedness to fit research norms have, of course, been much discussed (see [21] [22] [23]). Meanwhile, by moving away from rather narrow, text-based definitions of performance practice as a set of conventions whereby performers seek to achieve the ‘authentic’ reproduction of a score or a range of problem-solving techniques that they use to help them realise a composer’s artistic vision, it can be viewed more broadly, and creatively, as encompassing “all aspects of the way music is and has been performed”[24].

In this way, performance practice becomes a multi-faceted and inclusive body of musical activity that incorporates the diverse activities of modern musicians alongside those we associate with earlier and more established repertoires. This definition can form the basis of reciprocal interaction with research practice, whereby both inputs and outputs can be performer-led. Moreover, it takes into account not only performers and composers, but also the wider environment such as concert programmers, publishers, record labels, and audiences, putting into context the impact of research on this wider group. The heuristic process of changing technical practice by releasing research outputs into this widely-defined performance practice sphere might be frustrated by some parts of the process lagging behind others but, in the context of active participation between performance and research practice and formats, there is opportunity to manage this and to create a delivery strategy that meets performers’ needs.

Cello multiphonics

back to top

I described above an ideal working environment in which to undertake use-inspired performance research in an iterative process that cycles between theory and practice, and the context and opportunities presented by integrating performance and research practice. In a research fellowship in cello multiphonics at the Hochschule für Musik, Basel, I aimed to establish such an environment and use such opportunities. My objectives were to investigate cello multiphonics in order to describe them more precisely than previously (in terms of pitch content, loudness, colour, playing technique, etc.), and to present these results in a practical resource for musicians taking the form of a smartphone app. In my methodology, I attempted to build upon previous work, to put musicians’ agency and creativity at the focus of my approach and to create outputs that would impact both research and performance practice.

First, I reviewed the literature regarding research practice and performance practice into multiphonics. In the context of such a review, the success of the woodwind model becomes clear. The probably improvisation-led introduction of the technique by saxophonist John Coltrane, recorded in Harmonique 1959, was followed by Bruno Bartolozzi’s first notations in New Sounds for Woodwinds, which took the form of fingering charts for flute, oboe, clarinet, and bassoon[25]. The practice-driven nature of Bartolozzi’s experiments, but also his understanding of the importance of connecting these with the world of scientific research, is clear from the book’s preface:

Results of investigations have been arrived at only by practical experiment and not through scientific research. This is inevitable [because] scientific research lags very much behind the practice which this thesis proposes…It is to be hoped that science will furnish explanations for many perplexing phenomena.[26]

Bartolozzi’s call for scientific research in New Sounds was answered by acoustician Arthur Benade, who provided a physical explanation of the technique, crediting both Bartolozzi and Coltrane[27]. In the following decades, Bartolozzi’s fingering charts were corrected and updated, and the fingering chart structure was refined and subcategorised according to musical considerations such as loudness and ease of production. Multiphonics fingering charts now exist for saxophone[28], oboe[29], bassoon[30], clarinet[31], and bass clarinet[32] [33], and the technique is well integrated into composition and performance practice, despite irregularities in the various cones, tubes, and keys of woodwind instruments causing diversions from the standardised charts that necessitate corrections and adaptations. The pioneering figure of Bartolozzi, who called so convincingly for research at the outset of the technique, his combining of results for several instruments, and the clean organisation of woodwind techniques into fingering charts, to which the instruments are predisposed, gave significant advantages in terms of performance practice compared to strings.

Regarding stringed instruments, the origins of multiphonics technique are also likely to be in improvisation; using pictures of double bassist and improviser/composer Ferdinando Grillo playing with the bow placed between finger and bridge (a common multiphonics technique), Håkon Thelin convincingly dates the emergence of the technique to the 1970s[34]. The first fingering charts for string players were produced by John Schneider in The Contemporary Guitar[35]. However, there followed a hiatus in both research and practice, during which, although multiphonics were discussed and notated in some musical scores, findings were not concretised. In 2009, Marc Dresser presented some practical playing tips in The Strad[36] and, in 2012, a breakthrough in scientific understanding was led by Knut Guettler and Håkon Thelin, who described the technique physically as a filtering of overtones and undertook spectral analyses that pinpointed the pitch content of some multiphonics[37].

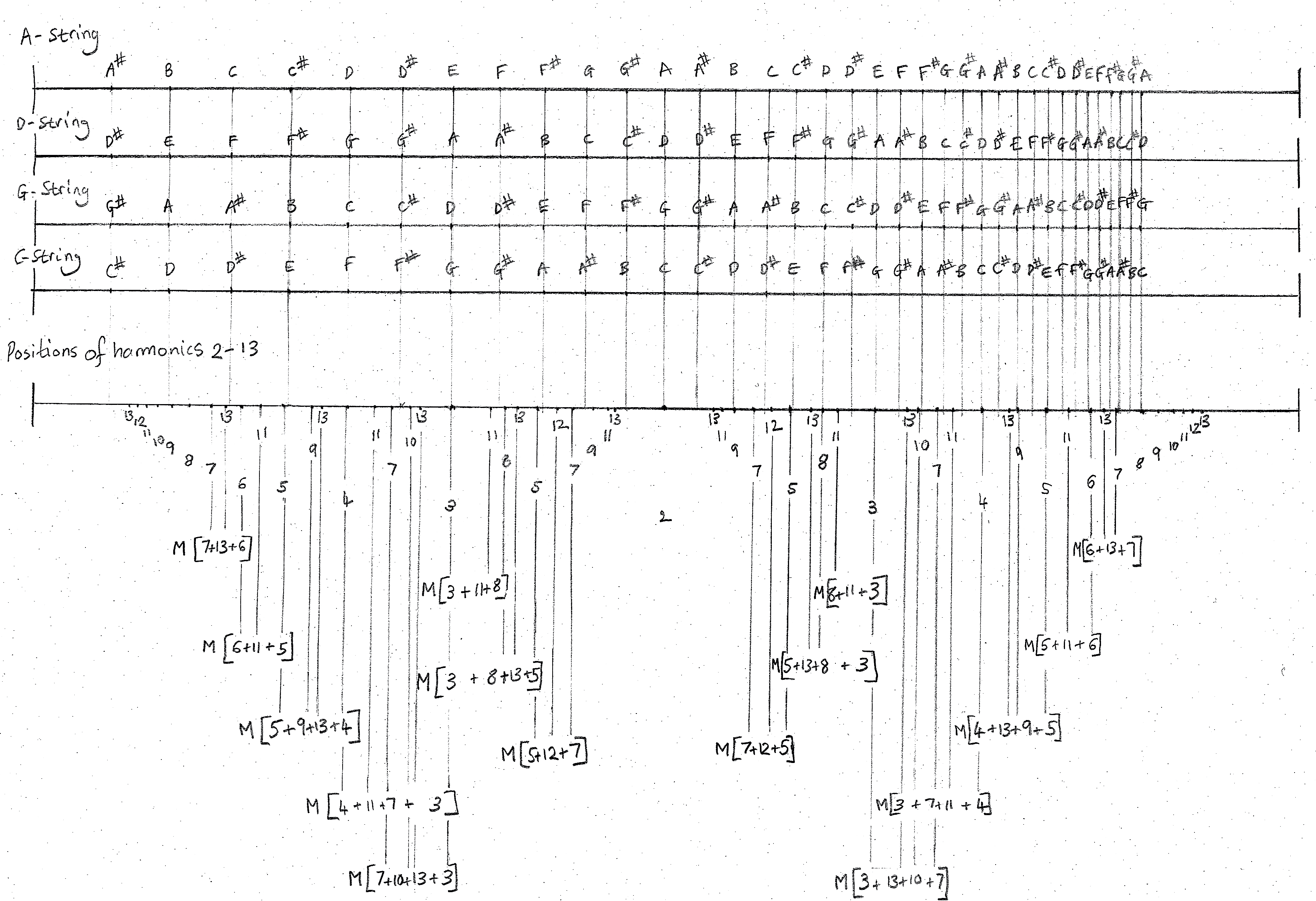

There followed in quick succession my own publication of 8 multiphonics on each cello string[38], charts for 18 multiphonics on the lower three guitar strings[39], and two multiphonics for violin and viola[40]. In 2014, Caspar Johannes Walter published fingering charts for piano and an algorithm to predict the pitch content of string multiphonics, providing an infinite list of combinations of harmonic components that could theoretically be generated on any stringed instrument[41]. Recognising in the woodwind model the apparently stabilizing nature of scientific input and links between instruments, I firstly defined a string multiphonic as: a single excitation by which two or more harmonics sound distinctly and simultaneously on one string. In other words, a multiphonic is a special case of harmonics such that several harmonics can be heard to sound in a chord at the same time. This can be seen in the original string sketch published on Cello Map, where nodal points for several harmonics are shown alongside their multiphonic combination, mapped against the semitonal scale plotted along each string’s length.

Chart 1: A sketch of the cello string showing semi-tonal

positions, the positions of the first 13 harmonics, and 8 multiphonics

that include these harmonics. Taken from www.cellomap.com

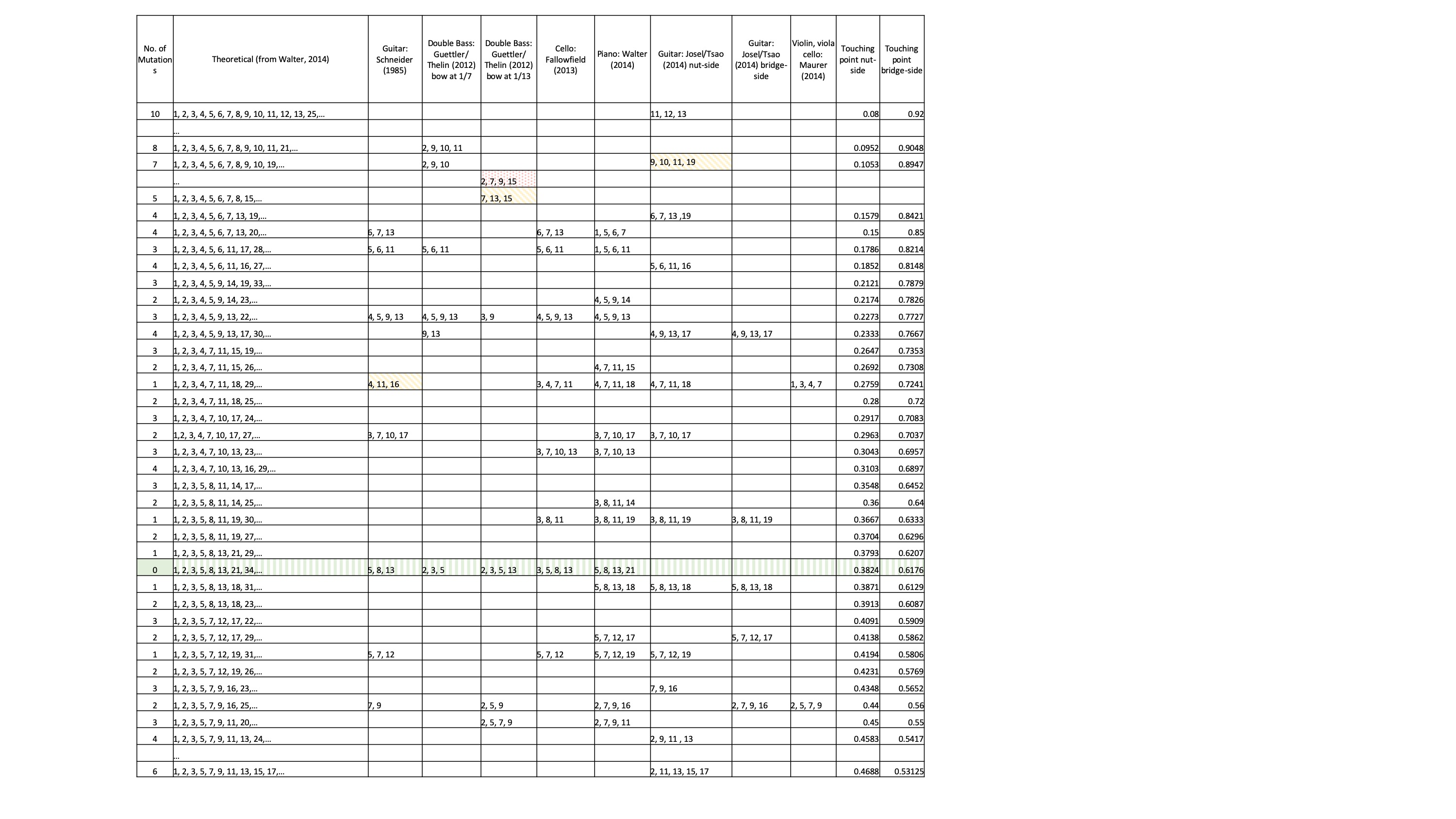

I then implemented Walter’s algorithm to generate a series of theoretical multiphonics with their upper bounds of pitch content fixed relatively high, and correlated these with the existing results for cello, guitar, double bass, and piano. This showed that existing results (achieved through empirical means) conform very well with Walter’s algorithm, and the results for various string instruments correlate very well with each other.

Chart 2: A table of fingering charts for string multiphonics showing

the theoretical results generated by Walter’s algorithm tabulated

alongside published results. The right-hand column shows touching

position as a proportion of string length. Yellow diagonal lines show

slight deviation from the algorithm. Red dots show large deviation

from the algorithm. Green horizontal lines show the ‘Fibonacci

multiphonic’, which is the route of the algorithm devised by Walter.

Reproduced with permission from Cambridge University Press.

I used this chart as a basis for expanding the list of 8 multiphonics that I had already published on Cello Map webpage (see Chart 1), in other words, to try to find multiphonics represented by the blank spaces in Chart 2. Theoretically these are all possible; the main questions, in terms of performance practice, are whether they are technically feasible and whether they are audible. The difference between two multiphonics that sit close to one another on the fingerboard is in the upper band of contributing harmonics: the lower harmonics are identical and, at a certain point, the upper harmonics split into two distinct branches. Technical feasibility is determined by the amount of control required in the bowing hand to decide whether the multiphonic is dominated by one branch or the other, and in the placement of the left hand, which, for branches that begin with very high harmonics, might lie a fraction of a semitone apart (the results described below summarize the work reported in detail in my article in Tempo [42]). To explore these parameters of feasibility, I made recordings with two cellist colleagues, rotating our three cellos (in an attempt to avoid ‘preferences’ according to player and instrument), trying to sustain particular multiphonics. I undertook spectral and frequency analysis of these multiphonics to determine which harmonic components contributed most strongly to the sound, and their intonation, and discussed with the cellists how controllable certain branches were. I also undertook a listening test with composition students at the Hochschule für Musik, Basel, asking them to describe the pitch content, relative loudness and intonation of the harmonic components of several multiphonics. The results of these analyses led me to a final list of 19 feasible multiphonics for each cello string.

In order to present these multiphonics in app form, I undertook a survey to determine what cellists and composers would require of such a tool. It quickly became clear that, in addition to multiphonics, practitioners were interested in a tool that organized harmonics. Although the theory behind string multiphonics is clear, and whilst I did not research them as part of this project, as the building blocks of multiphonics, harmonics could logically be integrated into the resource. Moreover, the ability to reach beyond a specialized group of interpreters and composers, and to have a broader appeal across the field of performance practice, motivated me to take this request seriously. I therefore incorporated the first 22 harmonics on each string into the resource. The availability of audio and video content, combined with clear musical notation, were important factors mentioned by practitioners. Thus, the app includes 249 audio recordings, 132 videos, and notations for every harmonic and multiphonic. There are also instructional videos regarding harmonic and multiphonic technique. The clarity gained by listening to the harmonic components of a multiphonic before the multiphonic itself was also reported as being helpful and, therefore, every multiphonics video begins in this way, as seen in the examples below.

Video 1: The Cello MApp video for II [3, 5, 8, 13], i.e., the multiphonic on the D string whose main components are harmonics 3, 5, 8, and 13. First I play the harmonics individually, and then the multiphonic.

Video 2: The Cello MApp video for III [3, 4, 7, 11], i.e., the multiphonic on the G string whose main components are harmonics 3, 4, 7, and 11. First I play the harmonics individually, and then the multiphonic.

Another aspect that was identified as important was the multiplicity of directions from which practitioners needed to access the information stored in the tool. Typical entry-point questions could be: What is the exact pitch of the 11th harmonic on the A string? Where do I put my finger, and on which string, to produce the pitch E6 quarter-tone-flat as a natural harmonic? Is / are there some multiphonics that includes the 7th and 11th harmonics on the G string, where do I play it/them? Is/are there some multiphonics that includes the notes A-sharp, D, and F, what does it / do they sound like and how can I notate it / them? In other words, it was necessary to create a multidimensional search function that enabled the user to access information from different starting points. I worked closely with software developer and composer Keitaro Takahashi to find a way to facilitate this my means of a filtering system that enables users to build branches based on the information required and to filter out irrelevant options. Below are screen recordings from Cello MApp showing the ‘answers’ to the questions listed above.

Video 3: In this screen recording, I apply the filtering system to find the pitch for the 11th harmonic on the A string, adjust the settings to show the pitch according to cent deviation, and choose a left-hand position from the 10 options.

Video 4: In this screen recording, I select the required pitch result, find out which string and which harmonic number it belongs to, and then chose three left-hand positions from the available 12 and compare the respective sound results.

Video 5: In this screen recording, I filter the list of multiphonics to include only those with the 7th and 11th harmonics on the G string. I compare the two results, choose one, and check the notation and video for more detail.

Video 6: In this screen recording, I filter the list of multiphonics to include only those with the pitches A-sharp, D and F (+/- a quarter tone). This generates one result. I check the notation and video for more detail.

The branch structure enables the user to compare several options: for example, the timbre of the various left-hand touching points for the 12th harmonic on the G string, or various multiphonics that include the notes B and G, as shown in the video examples below.

Video 7: In this screen recording, I apply the filtering system to find the pitch for the 12th harmonic on the G string. I select all of the four options for the left-hand finger positions and compare the sound.

Video 8: In this screen recording, I filter the list of multiphonics to include only those with the pitches B and G (+/- a quarter tone). This generates seven results. I select 4 of these, and compare the sound. I choose one and check the notation and video for more detail. Note, this screen recording was made on an iPad (the advantage of a larger screen in this case is clear).

Although I recorded exactly the same set of harmonics and multiphonics on each string, the sound quality varies from one string to another according to string length relative to width, and the psychoacoustic perception of high overtones. This can result in differences in sound quality between the four strings. For example, harmonics on the lower strings may sound a little thinner than those on the upper strings, and multiphonics on higher strings may sound denser, with less clearly decipherable harmonic components than on lower string. I decided that these differences were best presented in the form of the sound files, without further comment. All of the recordings were made in a controlled environment, and with microphones set at the same levels; thus, these differences are presented as accurately as possible. Moreover, the variation in technical difficulty is also audible in the recordings and, as I mention in the instructional videos, composers using the app can best determine these technical levels in collaboration with a performer. Harry Sparnaay set a precedent for this in his handbook for bass clarinet in which he deliberately leaves the recordings on the accompanying CD unedited to show the users which techniques speak instantly, and which are less reliable[43]. I consider this a reasonable and realistic way of dealing with ambitious technical material. Moreover, the differences in sound quality between the four cello strings are determinable through Cello MApp, as seen in the examples below.

Video 9: In this screen recording, I compare the sound of the 19th

harmonic on all four cello strings.

Video 10: In this screen recording, I compare the sound of multiphonic (6, 7, 13) on all four cello strings. This recording was made on an iPad.

Although I was able to present several key research findings within the app, there were others that could not be condensed in such a way. In order to show these, and to describe the workings behind the app creation, I prepared an academic paper. Having seen the strong correlation between the multiphonics on various stringed instruments, and noting the positive effect of cooperation between instruments in the case of woodwind multiphonics and in the literature more generally, I invited colleagues to describe the state-of-the-art in their practice, namely, harp[44], electric guitar[45], piano[46], and composition[47] [48], alongside my own contributions[49] [50]. These texts were published together in a Special Issue of Tempo. Each contribution shows the relevant technical issues for the instrument in question, and the various compositional interpretations that can be taken.

Some aspects of playing cello multiphonics that emerged as important during my research left open questions that were beyond the scope of the study at the time but are nonetheless of musical interest. I describe some of these below. The first concerns intonation. In contrast to the intonation of the open string, where the fundamental, open string pitch is most ‘in-tune’ and its overtones deviate from the harmonic series, becoming increasingly sharp as the harmonic series ascends due to string stiffness, the intonation of the components of multiphonics presents a different picture. Frequency analysis showed the intonation of the mid- and high-range overtones to be excellent, and that of the open string and second overtone to deviate strongly, fluctuating not only during a bow stroke but also within the decay of a pizzicato sound. Participants in the listening test that I undertook with students in Basel, however, perceived the multiphonics to be generally well in tune. It would, therefore, be interesting to know whether i) the ear corrects for these fluctuations, ii) the pitches, which are usually not dominant in terms of loudness, are perceived to be relatively unimportant in the sound, or iii) the fluctuation in intonation is perceived timbrally, rather than in terms of intonation, contributing to the slightly ‘muddy’ or ‘bell-like’ quality of a multiphonic.

Then, there is a question of right-hand contact point during multiphonic production. The contact points at which it is possible to produce multiphonics with the bow appear to be found in ‘pockets’ along the string; there are some areas where it is extremely difficult to produce multiphonic sound, and other areas where it is easier. The existence of these ‘pockets’ can be explained by the necessity to find an ‘acceptable’ contact point in the waveform of each contributing harmonic such that the respective harmonics can sound. However, in the spectral analysis, I was unable to characterize the difference in timbre between these pockets with a generalized ‘rule’. Nonetheless, the contact point clearly changes the musical character of the sound, as shown in the video below. Being able to characterize this change in more detail, both technically and musically, would be a valuable future goal.

Video 11: This video shows the ‘pockets’ of contact point on the

string where the multiphonic III (6, 7, 13) sounds. There is a clear

difference in sound quality as the contact point changes.

Of the remaining issues in performance practice terms, I perceive the

most important to be the use of cello multiphonics in an ensemble

context. The technique can be rather fragile, and there remains to be

developed a method of ‘orchestration’ so that the chord-like character

is not lost in a chamber music setting. I intend to explore this with my

string-player colleagues from the Special Issue publication in a

commissioning project next season, in which we will ask composers to

work with the results of our respective research to create new works

that use multiphonics on the cello, guitar, harp, and piano. I hope

that, by disseminating my work in the form both of an app and academic

publications, I will stimulate further work from instrumentalists and

composers, leading to new research results and new practices.

Bibliography

Bartolozzi, Bruno. New Sounds for Woodwind. Translated by Reginald Smith Brindle, 1st edn., (London: Oxford University Press, 1967) (2^nd^ edn printed in 1982).

Benade, Arthur, The Fundamentals of Musical Acoustics, 2nd edn., (New York: Dover, 1990). (1st edn. 1976. Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Bok, Henri, New Techniques for the Bass Clarinet (2nd edn.) (Rotterdam: Shoepair Music, 2011)

Brown, Howard Mayer, David Hiley, Christopher Page, Kenneth Kreitner, Peter Walls, Janet K. Page, D. Kern Holoman, Robert Winter, Robert Philip, and Benjamin Brinner. ‘Performing practice’, Grove Music Online. (2001) Oxford University Press. [accessed 9 November 2020] Visit ->

Ciszak, Thomas, and Seth F. Josel. ‘Of Neon Light: Multiphonic Aggregates on The Electric Guitar’. Tempo 74 (291). Cambridge University Press (2020): 25–49.

Clark, Terry, and Aaron Williamon. ‘Evaluation of a Mental Skills Training Program for Musicians’, Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. 23(2011):342-359

Clarke, Erik F., and Mark Doffman, eds., Distributed Creativity. Collaboration and Improvisation in Contemporary Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018)

Cook, Nicholas. Beyond the Score: Music as Performance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014)

Croft, John, ‘Composition is Not Research’, Tempo 69, no. 272 (2015): 6–11.

Doğantan-Dack, Mine, ed., Artistic Practice as Research in Music: Theory, Criticism, Practice (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015)

Dresser, Marc. ‘Double bass multiphonics’. The Strad, Vol. 120(1434) (2009): 72-75.

Einarsdóttir, Gunnhildur, ‘Multiphonics on the Harp: Initial Observations’, Tempo 74 (291). Cambridge University Press (2020): 71–75.

Fallowfield, Ellen, ‘Cello Multiphonics: Technical and Musical Parameters’, Tempo 74 (291). Cambridge University Press (2020): 51–69.

Fallowfield, Ellen, ‘Cello Map’ (2014). www.cellomap.com/ [Accessed on November 1, 2020]

Fallowfield, Ellen, ‘Rethinking Instrumental Technique’ in Rethinking the Musical Instrument ed. Mine Doğatan-Dack (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars, forthcoming)

Fallowfield, Ellen. 'Cello map: a handbook of Cello technique for performers and composers’ (doctoral thesis, University of Birmingham, 2010).

Fallowfield, Ellen ‘Cello Map App’ (2020) View on the AppStore [Accessed on December 17 2020]

Fox, Christopher and Ellen Fallowfield, ‘Editorial: The Art of the String Multiphonic’, Tempo 74 (291). Cambridge University Press (2020): 3–5.

Gallois, Pascal. The techniques of Bassoon Playing (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2010).

Guettler, Knut and Håkon Thelin, ‘Bowed-string multiphonics analyzed by use of impulse response and the Poisson summation formula’, Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, Vol. 131 (1) Pt.2 (2012): 766-772.

Jørgensen, Harald, ed. Teaching About Practicing (Oslo: Norwegian Academy of Music, 2015)

Josel, Seth F. and Ming Tsao, The Techniques of Guitar Playing (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2014)

Knox, Garth, Viola Spaces: Contemporary Viola Studies (Mainz: Schott, 2009)

Knox, Garth, Violin Spaces: Contemporary Violin Studies (Mainz: Schott 2017)

Maurer, Barbara. Saitenweise: Neue Klangphänomene auf Streichinstrumenten und ihre Notation (Wiesbaden: Breitkopf und Härtel, 2014).

Nicholson, Thomas, and Marc Sabat, ‘Farey Sequences Map Playable Nodes on a String’, Tempo 74 (291). Cambridge University Press (2020): 86–97.

Pace, Ian, ‘Composition and Performance Can Be, and Often Have Been, Research’ Tempo 70, no. 275 (2016): 60–70.

Rehfeldt, Philip, New Directions for Clarinet (2nd edn.) (Berkley: University of California Press 1994)

Rink, John, Helena Gaunt and Aaron Williamon, eds., Musicians in the Making. Pathways to Creative Performance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018)

Schmidt, Michael, Cappricio für Siegfried Palm (Regensburg: Con Brio, 2005)

Schneider, John, The Contemporary Guitar (1st edn.) (Berkley: University of California Press, 1985) (2^nd^ edn. 2015)

Sparnaay, Harry, The Bass Clarinet - A Personal History (Barcelona: Periferia Music, 2011)

Svoboda, Mike and Michel Roth, The Techniques of Trombone Playing (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2017)

Thelin, Håkon, ‘A New World of Sounds-Recent Advancements in Double Bass Techniques’. [Accessed on October 1, 2020] <http://haakonthelin.com/multiphonics/>

Veale, Peter and Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf. The Techniques of Oboe Playing (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1998)

Walden, Valerie. ‘Technique, style, and performing practice to c. 1900’ in The Cambridge Companion to the Cello, ed. By Robin Stowell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999) pp. 178-94.

Walter, Caspar Johannes, ‘Mehrklänge auf dem Klavier. Von Phänomen zur mikrotonalen Theorie und Praxis’, In Mikrotonalität-Praxis und Utopie, eds. Cordula Pätzold and Caspar Johannes Walter (Mainz: Schott, 2014) pp. 17-27.

Walter, Caspar Johannes. ‘Multiphonics on Vibrating Strings’, Tempo 74 (291). Cambridge University Press (2020): 7–23.

Weiss, Marcus and Giorgio Netti, The Techniques of Saxophone Playing (Kassel: Bärenreiter 2010)

Williamon, Aaron, ed., Musical Excellence (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004)

Yoshida, Sanae, ‘The Microtonal Piano and the Tuned-in Interpreter’, Tempo 74 (291). Cambridge University Press (2020): 77–84.

Appendix

Webpages and blogs for contemporary instrumental technique

Handbooks for contemporary instrumental technique (author, title, publisher, year of publication) arranged in chronological order

| Salzedo, Carlos. Modern Study of the Harp. Milwaukee: Schirmer. | 1921 |

| Bartolozzi, Bruno. New Sounds for Woodwind. Translated by Reginald Smith Brindle (1st edn.). London: Oxford University Press | 1967 |

| Smith Brindle, Reginald. Contemporary Percussion (1st edn.) London: Oxford University Press. | 1970 |

| Turetzky, Bertram. The Contemporary Contrabass (1st edn.). Berkley: University of California Press. | 1974 |

| Gümbel, Martin. Neue Spieltechniken in der Querflöten-Musik nach 1950. Kassel: Bärenreiter. | 1974 |

| Howell, Thomas. The Avant-Garde Flute. A Handbook for Composers and Flautists. Berkley: University of California Press. | 1974 |

| Dick, Robert. The Other Flute, a Performance Manual of Contemporary Techniques (1st edn.). New York: Multiple Breath Music Company. | 1975 |

| Rehfeldt, Philip. New Directions for Clarinet (1st edn.). Berkley: University of California Press. | 1977 |

| Dempster, Stuart. The Modern Trombone: a Definition of its Idioms. Berkley: University of California Press. | 1979 |

| Artaud, Pierre-Yves and Gérard Geay. Present Day Flutes. Paris: Jobert. | 1980 |

| Turetzky, Bertram. The Contemporary Contrabass (1st edn.). Berkley: University of California Press. | 1982 |

| Bartolozzi, Bruno. New Sounds for Woodwind. Translated by Reginald Smith Brindle (1st edn.). London: Oxford University Press. | 1982 |

| Kientzy, Daniel. Les sons multiples aux saxophones. Paris: Salabert. | 1982 |

| Hill, Douglass. Extended Techniques for the Horn (1st edn.). Miami, Florida: Warner Bros Publications. | 1983 |

| Inglefield, Ruth and Lou Anne Neill. Writing for the Pedal Harp: a Standardised manual for Composers and Performers. Berkley: University of California Press. | 1985 |

| Schneider, John. The Contemporary Guitar (1st edn.). Berkley: University of California Press. | 1985 |

| Riedelbauch, Heinz. Systematik moderner Fagott- und Bassontechnik. Celle: Moek. | 1988 |

| Bok, Henri. New Techniques for the Bass Clarinet (1st edn.). Paris: Salabert. | 1989 |

| Dick, Robert. The Other Flute, a Performance Manual of Contemporary Techniques (2nd edn.). New York: Multiple Breath Music Company. | 1989 |

| Dick, Robert. Circular Breathing for the Flutist. New York: Multiple Breath Music Company. | 1989 |

| Londeix, Jean-Marie. Hello! Mr Sax or Parameters of the Saxophone. Paris: Leduc. | 1989 |

| O’Kelly, Eve. The Recorder Today. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. | 1990 |

| Smith Brindle, Reginald. Contemporary Percussion (2nd edn.). London: Oxford University Press. | 1991 |

| Bach, Michael. Fingerboards and Overtones. Munich: Edition Spangenberg. | 1991 |

| Lehner-Wieternik, Angela. Neue Notationsformen Klangmöglichkeiten und Spieltechniken der Klassischen Gitarre. Wien: Doblinger. | 1991 |

| Rehfeldt, Philip. New Directions for Clarinet (2nd edn.). Berkley: University of California Press. | 1994 |

| Hill, Douglass. Extended Techniques for the Horn (2nd edn.). Van Nuys California: Warner Bros Publications. | 1996 |

| Veale, Peter and Mahnkopf, Claus-Steffen. The Techniques of Oboe Playing. Kassel: Bärenreiter. | 1998 |

| Strange, Patricia and Strange, Allen. The Contemporary Violin: Extended Performance Techniques. Berkley: University of California Press. | 2001 |

| Bok, Henri. New Techniques for the Bass Clarinet (2nd edn.). Rotterdam: Shoepair Music. | 2001 |

| Mabry, Sharon. Exploring Twentieth-Century Vocal Music: A Practical Guide to Innovations in Performance and Repertoire. New York: Oxford University Press. | 2002 |

| Levine, Carin and Mitropoulos-Bott, Christina. Translated by Laurie Schwartz. The Techniques of Flute Playing. Kassel: Bärenreiter. | 2002 |

| Krassnitzer, Gerhard. Multiphonics für Klarinette mit deutschem System und andere zeitgenössische Spieltechniken. Aachen: Edition Ebenos. | 2002 |

| Van Cleve, Libby. Oboe Unbound: Contemporary Techniques. Lanham Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. | 2004 |

| Edgerton, Michael Edward. The 21st-Century Voice: Contemporary and Traditional Extra-normal Voice. Lanham Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. | 2005 |

| Koizumi, Hiroshi. Technique for contemporary flute music for players and composers. Tokyo: Schott. | 2005 |

| Schick, Steven. The Percussionist’s Art: Same Bed, Different Dreams. Rochester: University of Rochester Press. | 2006 |

| Buchmann, Bettina. The Techniques of Accordion Playing. Kassel: Bärenreiter. | 2010 |

| Gallois, Pascal. The techniques of Bassoon Playing. Kassel: Bärenreiter. | 2010 |

| Weiss, Marcus and Netti, Giorgio. The Techniques of Saxophone Playing. Kassel: Bärenreiter. | 2010 |

| Sparnaay, Harry. The Bass Clarinet - A Personal History. Barcelona: Periferia Music. | 2011 |

| Arditti, Irvine and Platz, Robert. The Techniques of Violin Playing. Kassel: Bärenreiter. | 2013 |

| Isherwood, Nicholas. The Techniques of Singing. Kassel: Bärenreiter. | 2013 |

| Josel, Seth F. and Tsao, Ming. The Techniques of Guitar Playing. Kassel: Bärenreiter. | 2014 |

| Maurer, Barbara. Saitenweise: Neue Klangphänomene auf Streichinstrumenten und ihre Notation. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf und Härtel. | 2014 |

| Schneider, John. The Contemporary Guitar (2nd edn.). New York: Roman and Littlefield. | 2015 |

| Svoboda, Mike and Roth, Michel. The Techniques of Trombone Playing. Kassel: Bärenreiter. | 2017 |

| Shockley, Alan. The Contemporary Piano: A Performer and Composer's Guide to Techniques and Resources. New York: Roman and Littlefield. | 2018 |

| Dierstein, Christian, Roth, Michel, and Rouland, Jens. The Techniques of Percussion Playing. Kassel: Bärenreiter. | 2018 |

| Hübner, Paul and Burba, Malte. Modern Times for Brass: Experimental Playing Techniques for Brass Instruments. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf und Härtel. | 2019 |

| Adler-McKean, Jack. The Techniques of Tuba Playing. Kassel: Bärenreiter. | 2020 |

-

Nicholas Cook, Beyond the Score: Music as Performance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014) p.49. ↩︎

-

John Rink, Helena Gaunt and Aaron Williamon, eds., Musicians in the Making. Pathways to Creative Performance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018) ↩︎

-

Erik F. Clarke, and Mark Doffman, eds., Distributed Creativity. Collaboration and Improvisation in Contemporary Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018) ↩︎

-

Aaron Williamon, ed., Musical Excellence (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004) ↩︎

-

Terry Clark and Aaron Williamon, ‘Evaluation of a Mental Skills Training Program for Musicians’, Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. 23(2011): 342-359 ↩︎

-

Harald Jørgensen, ed., Teaching About Practicing (Oslo: Norwegian Academy of Music, 2015) ↩︎

-

Quantz, Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversiere zu spielen (1752); C.P.E. Bach, Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen, i (1753) Leopold Mozart Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule (1756) ↩︎

-

Walden, Valerie. ‘Technique, style, and performing practice to c. 1900’ in The Cambridge Companion to the Cello, ed. By Robin Stowell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999): 178-94. pp187–8. ↩︎

-

Schmidt, Michael, Cappricio für Siegfried Palm (Regensburg: Con Brio, 2005) p.89. ↩︎

-

Fallowfield, Ellen. 'Cello map: a handbook of Cello technique for performers and composers’ (doctoral thesis, University of Birmingham, 2010). ↩︎

-

Fallowfield, Ellen, ‘Rethinking Instrumental Technique’ in Rethinking the Musical Instrument ed. Mine Doğantan-Dack (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars, forthcoming) ↩︎

-

https://3dmusicinstruments.com ↩︎

-

https://www.hkb-interpretation.ch/projekte/contrabassclarinet-extended ↩︎

-

https://www.21stcenturyoboe.com/the-howarth-redgate-oboe/video-introduction-to-the-howarth-redgate-oboe ↩︎

-

www.cellomap.com ↩︎

-

Fallowfield, Rethinking Instrumental Technique ↩︎

-

Mike Svoboda and Michel Roth, The Techniques of Trombone Playing (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2017) ↩︎

-

Garth Knox, Viola Spaces: Contemporary Viola Studies (Mainz: Schott, 2009) and Garth Knox, Violin Spaces: Contemporary Violin Studies (Mainz: Schott 2017) ↩︎

-

Mine Doğantan-Dack, ed., Artistic Practice as Research in Music: Theory, Criticism, Practice (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015) ↩︎

-

John Croft, ‘Composition is Not Research’, Tempo 69, no. 272 (2015): 6–11. ↩︎

-

Ian Pace, ‘Composition and Performance Can Be, and Often Have Been, Research’, Tempo 70, no. 275 (2016): 60–70. ↩︎

-

Howard Mayer Brown et al., ‘Performing practice’, Grove Music Online. (2001) Oxford University Press. [accessed 9 November 2020] Visit -> ↩︎

-

Bruno Bartolozzi, New Sounds for Woodwind. Translated by Reginald Smith Brindle, 1st edn., (London: Oxford University Press, 1967) (2^nd^ edn printed in 1982). ↩︎

-

Ibid. p.6 ↩︎

-

Arthur Benade, The Fundamentals of Musical Acoustics, 2nd edn., (New York: Dover, 1990). (1st edn. 1976. Oxford: Oxford University Press) ↩︎

-

Marcus Weiss and Giorgio Netti, The Techniques of Saxophone Playing (Kassel: Bärenreiter 2010) ↩︎

-

Peter Veale and Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf, The Techniques of Oboe Playing (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1998) ↩︎

-

Pascal Gallois, The techniques of Bassoon Playing (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2010). ↩︎

-

Philip Rehfeldt, New Directions for Clarinet (2nd edn.), (Berkley: University of California Press 1994) ↩︎

-

Henri Bok, New Techniques for the Bass Clarinet (2nd edn.), (Rotterdam: Shoepair Music, 2011) ↩︎

-

Harry Sparnaay, The Bass Clarinet - A Personal History (Barcelona: Periferia Music, 2011) ↩︎

-

Håkon Thelin, ‘Historical Notes’ [Accessed November 1, 2020] Visit -> ↩︎

-

John Schneider, The Contemporary Guitar (1st edn.) (Berkley: University of California Press, 1985) (2^nd^ edn. 2015) ↩︎

-

Marc Dresser, ‘Double bass multiphonics’. The Strad, Vol. 120(1434) (2009): 72-75. ↩︎

-

Knut Guettler, and Håkon Thelin, ‘Bowed-string multiphonics analyzed by use of impulse response and the Poisson summation formula’, Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, Vol. 131 (1) Pt.2 (2012): 766-772. ↩︎

-

Ellen Fallowfield, ‘Multiphonics. Basics’ [Accessed on November 1, 2020] <https://cellomap.com/multiphonics-basics/> ↩︎

-

Seth F. Josel and Ming Tsao, The Techniques of Guitar Playing (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2014) ↩︎

-

Barbara Maurer, Saitenweise: Neue Klangphänomene auf Streichinstrumenten und ihre Notation (Wiesbaden: Breitkopf und Härtel, 2014). ↩︎

-

Caspar Johannes Walter, ‘Mehrklänge auf dem Klavier. Von Phänomen zur mikrotonalen Theorie und Praxis’, In Mikrotonalität-Praxis und Utopie, eds. Cordula Pätzold and Caspar Johannes Walter (Mainz: Schott, 2014) pp. 17-27. ↩︎

-

Ellen Fallowfield, ‘Cello Multiphonics: Technical and Musical Parameters’, Tempo 74 (291). Cambridge University Press (2020): 51–69. ↩︎

-

Sparnaay, The Bass Clarinet ↩︎

-

Gunnhildur Einarsdóttir, ‘Multiphonics on the Harp: Initial Observations’, Tempo 74 (291). Cambridge University Press (2020): 71–75. ↩︎

-

Thomas Ciszak and Seth F. Josel. ‘Of Neon Light: Multiphonic Aggregates on The Electric Guitar’. Tempo 74 (291). Cambridge University Press (2020): 25–49. ↩︎

-

Sanae Yoshida, ‘The Microtonal Piano and the Tuned-in Interpreter’, Tempo 74 (291). Cambridge University Press (2020): 77–84. ↩︎

-

Thomas Nicholson and Marc Sabat, ‘Farey Sequences Map Playable Nodes on a String’, Tempo 74 (291). Cambridge University Press (2020): 86–97. ↩︎

-

Caspar Johannes Walter. ‘Multiphonics on Vibrating Strings’, Tempo 74 (291). Cambridge University Press (2020): 7–23. ↩︎

-

Fallowfield, ‘Cello Multiphonics: Technical and Musical Parameters’ ↩︎

-

Christopher Fox and Ellen Fallowfield, ‘Editorial: The Art of the String Multiphonic’, Tempo 74 (291). Cambridge University Press (2020): 3–5. ↩︎