Project description:

My first ideas for this project were ideas of the decommissioned airport as the Auditorium and Cinematic Space. Or, the Airport as An Image Maker.. I asked myself: How does the airport retain images? How can I think about the airport as a Projector? An Identifier? A fleeting and transient Image Maker (of x-rays, visitors badges, travelers snapshots). The airport both connects and projects stories. It is both the beginning and the end of an event.

The more I thought of a large scale response to my questions, the more I was drawn to something very small. This seemed to resonate with the transitoriness of airports. The transient gesture as a small gesture.

As I further examined my response to the site I was drawn to ideas around short durational time (jetlag and my 2 day visit from Brooklyn), the space as an 'archeological site' and my findings while digging through left-behind electronic trash (digital artifacts). Drawing from ideas around 2,9777 found small jpegs of airport visitors in the 90s (all less than 200k), of identity and identification, and the site as a cinematic apparatus I am creating 3-5 cine-sculptures made from parts that will all travel with me from Brooklyn.I draw from ideas around the airport as a cinematic apparatus: taking photos (eyescans, ID cards), non-recorded events (x-ray), global media culture (tv-screens), stories (visitors, workers), and training and how-to videos (repeated practicalities).

The ultimate project is a culmination of architectural archeology and experimental cinema.

for paul.

so i am leaving soon and feel both excited and questioning (in a good challenging way) as to what the project will be. it seems like its creating questions regarding my own art process and methods - so accustomed to collaborations and now working in a new way. all seemingly tying into the overall idea of TC. curious as to how the site visit - as short as it is - could be a time to somehow "produce" work or simply respond to the site and whatever space you have in mind for my piece - and see how this will dictate my direction. curious and excited to work more site specific than usual.

i feel there is an interesting limitation to time.

(personal email comunication)

“And the person or thing photographed is the target, the referent, a kind of little simulacrum, and eidolon emitted by the object which I should call the Spectrum of the Photograph, because the word retains, through its root, a relation to “spectacle” and adds to it that rather terrible thing which there is in every photograph: the return of the dead.“

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida

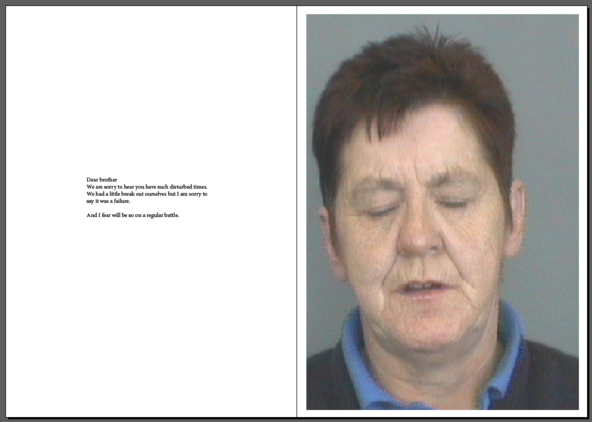

Dear brother.

We are sorry to hear you have such disturbed times. We had a little break out ourselves but I am sorry to say it was a failure and I fear will be so on a regular battle.

You say Roary of the Hill is shooting down odd ones? Well if you were here for a while you would not think much of that. They think little of shooting down a man here and they rarely make mention of it in the republic papers.

I wont discourage or encourage you if I told you the whole truth about the country. It is one a man can make money in fast, if god spars him health and look, but it’s a long a dangerous journey however.

(old scanned immigration letters, found at Cork Airport in the trash)

Perhaps they are all different small stories: The glove, found in multiples all over town like an amputated appendage, striking in its life-like form. The wounded animal, a piece of cloth, picked up from the street and re-photographed in my studio, only fully manifesting itself as an injured animal once through the printing machine, size accentuating form and story. The dream catcher – an abstract protective charm - a collage of found objects revealing itself by happenstance once on the wall in the exhibition space, appearing as a spiritual token to the caretaking of the land. The rust from old mattress springs found in an empty transitional lot just off the industrial road in town, swept off the floor in the studio, ready to be thrown out but instead re-shaped and formed by its own spring and turned into a small-scale studio installation, the real world once or twice removed. The ghost of Olof Palme and the mythical cement bunker nested in the middle of nature as from another planet. The soil and bits of metal from a burned car, re-shaped and re-introduced as a deconstructed image floating above the floor, a preserved small tree in a petrified form. A micro world of real grass from the actual landscape and cement chards from the newly constructed carcasses of modernity, a 1000-year-old field and the destruction of the man-made colliding in a gentle and miniscule installation-within-the-installation format. Dreams of a path as a passage through a landscape without an arrival and the act of building with history and land, a formation of barn structures all from scratch, related to me from the almost indecipherable pages of a century-old diary text. Of the still image becoming a film becoming a still image again and of folding and distilling time. *****

(A few) ideas collide. The excavation and investigation into image making and the photographic portrait, that of speed (cultural, travel) and this notion of being rooted and the relationship we have with our land, language and history. Text and a final work are connected but separate. The merger and combining of several archives creates a whole, a distilling of a few found components into much smaller gesture: the artist book. A book that drifts and flickers between photographic images as a medium. I am re-photographing, re-arranging, re-purposing as a way to experiment with contexts and the artist book. All found images, in a sense.

“The idea of “transformation” and “instability” is always tangible; films are transformed into texts and texts into films. Pauses, or intervals, are used in all the works, to express a sense of lost time in the interstices between the frames. This is critical for representing movement, but unseen – its “discontinuity” disappears into the continuous flow.”

Rosa Barba, A fictional Library, CAC, Vilnius 2014

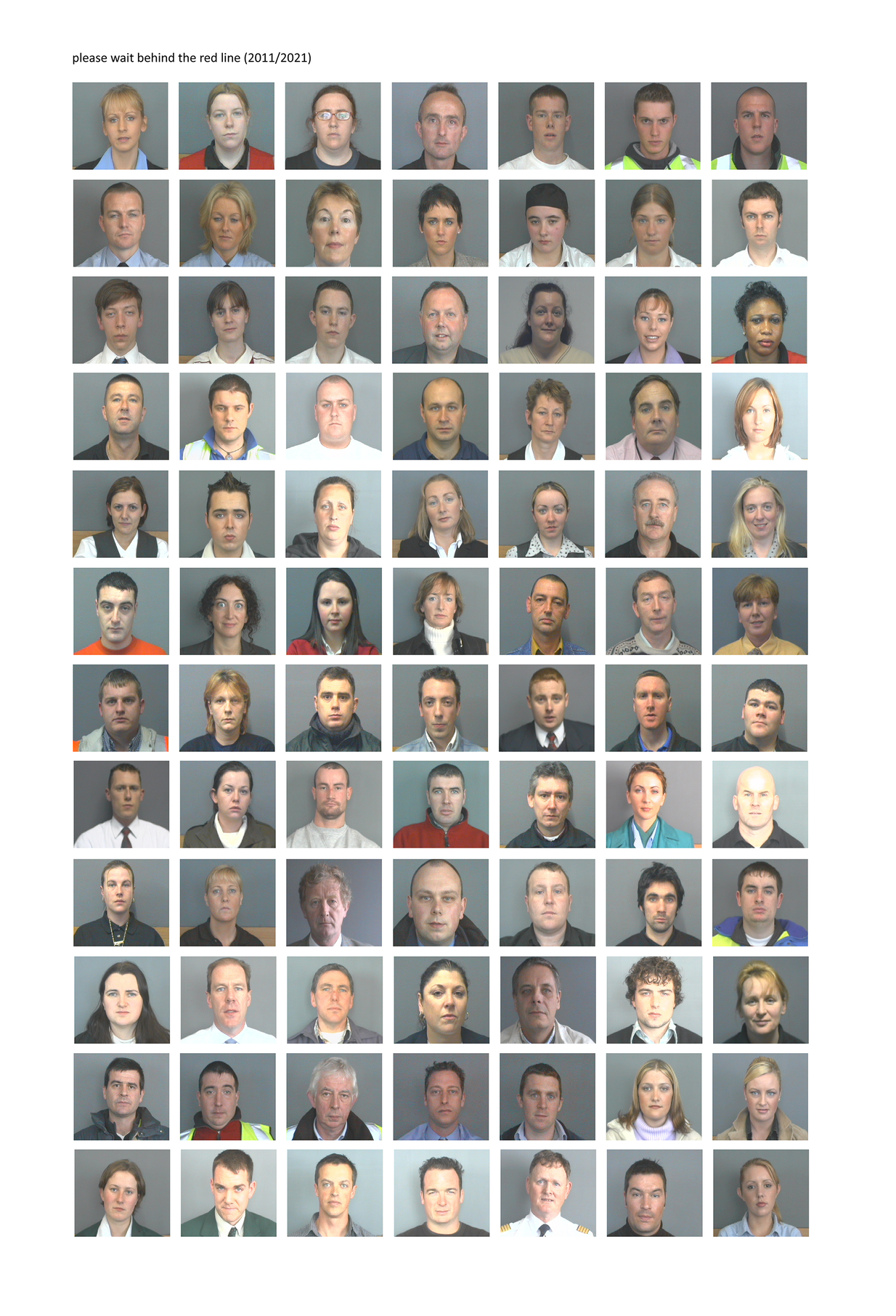

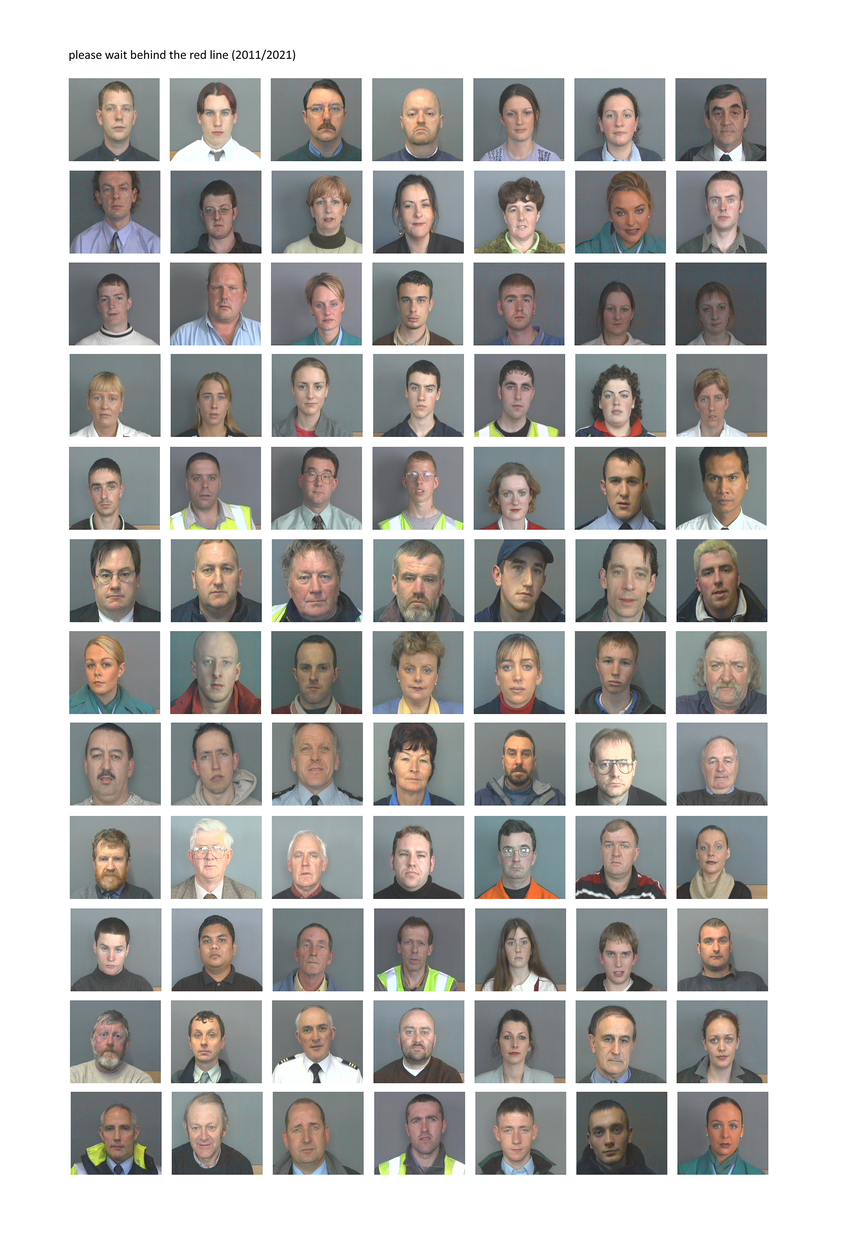

The exposition please wait behind the red line (2011/2021) is an attempt at taking a set of unearthed and found low resolution images and giving them new meaning and importance. And as an extension, they become an archive. The images were made in one specific time. I found them many years later, already removed from their original intent. By using them as a departure point for an art work in 2011 I connected them by happenstance back to their original usage. And by returning to them once again in 2021 they become a way for me to make new work out of existing work, explore the airport a place for stories, and to connect and reflect on aspects of photographic practices as well as my own practice which, in many ways, is situated in both the still and the moving image but where I have increasingly been searching for ways to experiment with and to find new strategies to expand on what the documentary can be, how to work with real-life material, and to offer new readings, constructions and narratives. Making new work out of previous work exploring different layers of time are of interest and create new openings for contextualizing.

So this further excavation and distilling of an unintentional archive is reworked it into an artist book, possibly in box form. From found homemade CD to a unique box as a small, gentle gesture, intervention and artistic response. Parts of the book is presented in the exposition. A PDF of a full first rough of the book will soon be accessible for download.

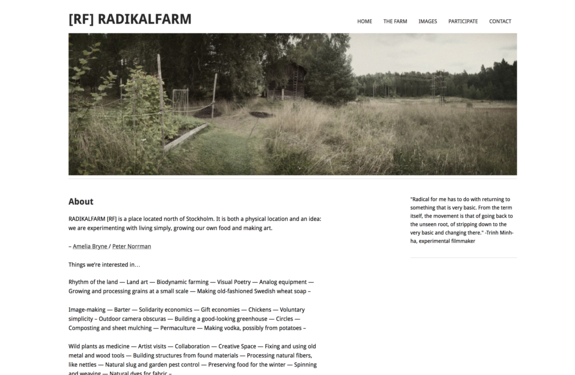

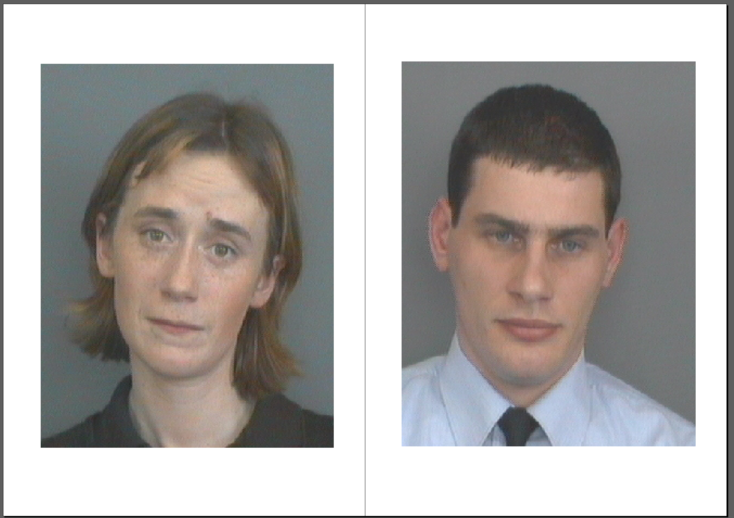

The images in this archive are all security and ID images created for the identification purposes of visitors to a now decommissioned former international airport in Cork, Ireland. They are pilots, stewardesses, construction workers, duty-free employees, family members. In addition I am interested in what happens when images are renegotiated from their initial purpose and to give multiple readings and contexts to a simple set of found images. In a more simple way, parts of the material can also be seen as photographic portraits, striking on their own, but also strong in a juxtaposed, reshaped and montaged context. They hover close to the history of photography steeped in the wish and trials of capturing the human face but go further as they touch upon both the history of forensic photography as well as unknowingly become a perspective into an early transition between the analog and the digital image. As please wait behind the red line (2011/2021) is centered around the 2977 images excavated from a trash pile in a decommissioned airport in 2011 the project further explores a timescale by returning to, and reworking and re-negotiating an earlier work of mine. In this exposition I return to ideas and research from my earlier piece in 2011, in an attempt to touch on ideas around security/safety/protection; the process of excavating the photographic image as well as ideas around “deferred time”*. I am also gazing at the material in the context of our current global situation where the Cork Identification Archive (CIA) seem to allude to both a post 9/11 world and a post COVID-19 world where travel, globalization and our sense of collective security is being questioned. Will the new normal be a more isolated world and what happens when we confront our notion of what it means to be rooted? By juxtaposing existing archives - the ID and security images (portraits) from the CIA material with images from my own archive(s) I am initiating the new work; a return to the portraits I have accumulated in my own photographic work as well as abstract images of found objects and landscapes created during life at radikalfarm (RF), a physical location and idea north of Stockholm (an experiment in living simply and an attempt at slowing down). It has been further abstracted and reworked in an attempt to add a layer of a contemporary intervention. And as yet another artistic strategy, one that would come after the text /work of this exposition, and deepen what is begun in the artistbook: to completely leave the documentary and claim that this archive is from the future. A future archeology of sorts. The potential to situate the material within a fictional future; a nameless airport after the big lockdown, intrigues me, as it is an artistic approach that would be somewhat new to me. A lot of my work seem to take on a slight dystopian or strange or otherworldly sensibility as is, so perhaps the leap is less big than I envision.

ideas of x-raying are floating around in my head. x-raying the ghost of that architecture. getting my hands on past footage created by the architecture/space (surveillance), flight patterns, migratory patterns, video mapping, sound recordings.

In 2011 I was invited to a group show in Cork, Ireland to respond to a decommissioned former international airport, no longer in use, but with a ghost-in-a-machine resonance still inescapably ingrained within the architecture. My 2 day site-visit gave me free limit to observe, scavenge, film and collect. I even spent the night within the structure, alone but thrilled to sleep on an 80s carpet somewhere between the micro historic shadows of the tax-free store and departure gates. The methodology of scavenging for archival material was not new to me. As both the keeper of my small family’s history or collecting 15 years of Brooklyn street junk as a means to make sense of my rapidly changing neighborhood, none of this practice materialized itself into my more serious artistic work. It was during a previous sitevisit, this one in Liverpool in 2008, that the archival cinema I was interested in merged with a more hands-on process, itself akin to a contemporary archeological methodology with a deep diving into dusty photographic archives and a clearer focus on research. None of this was in any sense reinventing the wheels but it was nevertheless an opening for me to start an inquiry into materiality based archives, histories of photo based analog and digital image making, questions around collective memory, and the public sphere as a means to - literally and conceptually - project image based stories.

When reading Hito Steyerls In Defense of the Poor Image I became interested once again in revisiting the images found in Cork and look at them more closely as images in themselves (and as less with the original departure point). The Cork Identification Archive were mainly produced between April 1997 and October 2002 with a few more in the subsequent years. The latter JPEGS differ only in the aspect of slightly higher resolution landing somewhere in the 130k area. They are interesting to me for this very reason: as poor images the extremely low resolution seem extremely outdated in our excessive HD +plus world. Or 4K, with the noted capital K (and not k), a connotation to image quality and luxury to further our problematic descent into a never ending fictitious pixel world. But they are not obsolete. The JPEG codec still readable within my computer system. And even in todays standard they would have a function as a small image for ID representation. So in essence they seem to represent a time in our digital image making history that is both a past (first generation low-res digital cameras) and a present (not obsolete). Steyerls text and my piece were made only years apart (2009/2011), a lifetime ago in context of digital life. But they create connection, if only for me. That connection is also the 10 year lifeline to our present time (2021) which ads further layers in context of a reading of the Cork Identification Archive. To think about some random low-res images found in heap of trash, under a staircase, in a decommissioned airport in a place I am disconnected to, makes a return to these images the more alluring to me. When Steyerl talks about the poor image as “an illicit fifth-generation bastard of an original image” and that is “mocks the promises of digital technology” I am suddenly made aware of the fact that this archive of found images are interesting and significant since they are the originals. They have not been “ passed on as a lure, a decoy, an index, or as a reminder of its former visual self” but certainly can be seen as “a lumpen proletarian in the class society of appearances, ranked and valued according to its resolution”(Steyerl). They are the promise of the future. The 59k file is not a “rag” of its former self but a true representation of the ones and zeros made during a short period at the end of last century when all the lure of the digital seemed acutely exciting and scintillating. It was during this time that I spent one year at the Interactive Telecommunications Program (ITP) in New York, immersed in the excitement and pull of the exploding world of new media, joining forces with an acclaimed-to-be cross-media performance collective where the clash and the connectivity of old and new media and the mediated pull of contemporary society was at the core of what the work explored. Cinema was being expanded once again, where the smaller digital mpeg files could forgo any inconvenient external hardware existence and start living solely on your powerbook. It was freeing, it was live and it was luring. Fully remembering this today seems a little futile with so many cycles of micro revolutions in digital production and new technologies. The fetishism of nostalgia in tech culture (cassette tapes, 4:3 ratios) plays out like as a stuttering reaction to a hyper reality that offers even more promises but with the inevitable fear of losing a sense of realness. But what is this perception of realness? I return to the Cork Identification Archive (CIA) with a more conceptual approach, trying to understand what they stand for beyond their initial purpose. The added layer of time displacement intrigues me. 2001/2011/2021. To both look at my own previous work as an archive that can be re-worked and re-conceptualized as well as going deeper into the concept of these found images as an archive in their own. If nothing else because I define them as that. “The poor image thus constructs anonymous global networks just as it creates a shared history. It builds alliances as it travels, provokes translation or mistranslation, and creates new publics and debates. By losing its visual substance it recovers some of its political punch and creates a new aura around it. This aura is no longer based on the permanence of the “original,” buton the transience of the copy” (Steyerl). Since their inception, these extreme low resolution photographs were only used twice (as far as I can understand): for their original purpose of creating a daily identification tagging of workers and visitors to an international airport active in the 1970s-90s - and as repurposed images as part of an art work in 2011. Their initial history and identity was altered by my intervention.

But with the original history lost, another history, and this impossible to have predicted, unfolded. In the exhibition space, unrelated to the original conception of the piece, a new translation of the past and the present revealed itself. The images, now contained and projected within my cine-sculptures, attracted through hearsay family and relatives of the people in the photographs. I found them hovering around the main sculpture, slowly following the sequence of projected faces, focused on the possibility of seeing a father or a friend or a sibling from a tangible past. A social space created itself. The images private yet again but only for the duration of the exhibition. The title RETAIN allures to this notion, the act of retaining some aspect of a ghost-in-the-machine. But to also look at found material as a way to translate history and space and concepts around image making into a new reality. “The poor image is no longer about the real thing – the originary original. Instead, it is about its own real conditions of existence: about swarm circulation, digital dispersion, fractured and flexible temporalities. It is about defiance and appropriation just as it is about conformism and exploitation"(Steyerl).

Cinema interested me enormously for its kinematic roots; all my work is dromological. After having treated metabolic speed, the role of the cavalry in history, the speed of the human body, the athletic body, I became interested in technological speed. It goes without saying that after relative speed (the railroad, aviation) there was inevitably absolute speed, the transition to the limit of electro-magnetic waves. In fact, cinema interested me as a stage, up to the point of the advent of electromagnetic speed. I was interested in cinema as cinematisme, that is the putting into movement of images. We are approaching the limit that is the speed of light.

(Paul Virilio, Wired Magazine)

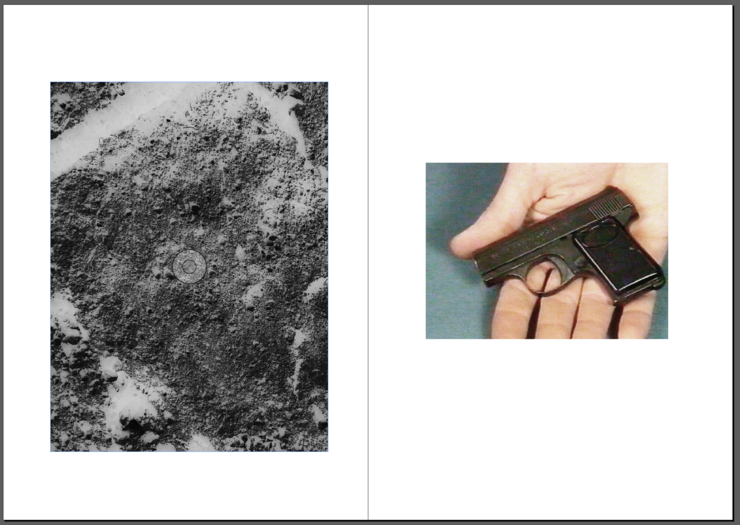

The piece RETAIN (2011), shown at the international group show Terminal Convention in Cork, came to be by immersing myself into a new sort of digging where I was interested in the airport as an archeological site, a once active space of fleeting and transient stories. As an artist I tend to be more reactive, needing a situation or existing fragment that I can respond to. While roaming the desolate airport areas and former restaurants and baggage belt zones, it felt like time had stopped sometime in the mid-80s and the airport was quickly abandoned due to some extraordinary event. I had set my eyes on a large, old discarded monitor system, outdated tech as a phantom information device, re-purposed for a contemporary image apparatus. The airport both connects and projects stories. It is both the beginning and the end of an event. While digging through left-behind electronic trash, I came upon several old CD’s containing, in all, 2,977 small jpegs of airport visitors in the 90s. They were in essence the left behind stories of identity and identification. These early digital artifact, most of them less than 150k in resolution, became the departure point for my piece, using them both as a social connector of layers of histories, locality and geography as well as the material for my inquiry in early low- res digital image making, old reconfigured technologies and architecture as a cinematic apparatus in itself.

"Resonances. Intersections. Broken structures. Intervals. Interstices.” The cinematic parts are cohesive nodes of what is expanded and contracted specifically and variably in spatial conditions, some with a precise, yet slipping, resonance, and also contrapuntally, rhythmically in relation."

Renee Green, Certain Obliqueness (2016)

The archive seem to exist in both a past and a present. Both an action of slowing down in front of the security camera and be part of supporting the systemic ways of the events of speed the airport. As ephemeral and transient images they maneuver the very early edge and promise of the digital revolutions beneficial speed for life and cultural improvement and image sharing. Today we all know the overload we experience. In comparison to the millions of other amateur photographs taken, these 2977 JPGS were not meant for broader consumption nor a spot in the family album but instead to be discarded, or to cease to have any importance after a mere 24 hrs. As a collection of images, in its most raw archival form, they are permanently connected to the airport. When doing research in 2011 I became interested in the airport as a transitional space. As place where stories collide. But also as architecture that can be translated into a cinematic structure. Today, it is a place in limbo, with global COVID creating an unknown as to how it will play out. Will we decide that travel is less important and that immobility does not necessarily mean isolation? We are at still a pause more than 1 year later. An interim. An in-between.(by now starting to break open again.) When Paul Virilio, decades ago, spoke about a world which is suffering from the “disease of speed” I become confronted with what these images tell me beyond being a sort of stand-in for the millions of despondent and unemployed and perished humans in the world right now. What will it mean for us if we continue to stay more rooted, a relationship that historically a population has nurtured with its land, its language, and its history? Will a post-covid world reduce the world even more in context of physical movement. Screen time is real-time. Real life is delayed time. We move forward living in a “deferred time” (Virilio). There was another folder on the same CD as the identification images, this one with family photographs from the irish Farrelly family, dating back to the late 19th century, as well as scanned old letters with incredible personal writings from the american frontier in the 1870s, the violence and the hardship. But what stood out for me were the constant offerings of cross-atlantic movement; sending for a wife or brother or returning to sell some land only to travel back to Salina, CA with a new sense of possibilities. Some stay. Some go. The fluidity of travel even back in those days of uprooting and endless goodbyes seemed so modern. Today, though, something will have to change. Arundhati Roy writes: “Nothing could be worse than a return to normality. Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.” So where my initial research around bodies in motion, jetlag and speed (travel, cinema) seemed connected to a global situation of yesterday, returning to the same material 10 years later - with life still immersed in an unknown - yields a different reading beyond the excavation and investigation into image making and the photographic portrait. Or perhaps it is less the mages themselves and more where they are situated. The airport. Can a sedentary and more idle lifestyle provoke the global changes so desperately needed, specially when it comes to ecology and the climate? Or are people (mainly in the western world) - 1 year into this global shift - mainly too used to living in a delayed time, short term behavior, and too eager to get back into the skies when they can? Travel is and will be different. The world is reduced. Navigating the crossing of borders will be different. So using the dystopian vision of an abandoned large airport seems like an interesting additional departure point for a further artistic investigation.

The collector is disturbed by the fact that things are scattered in the absence of context. He wants to unite what belongs. He wants to concentrate.

(Intro Walter Benjamin och Asj, Essä Page 284)

This exposition is an attempt to define an archive as well as intervening into this very archive. It examines and explores a simplified artistic process, a critical response perhaps to my own previously more complex work. But the site-visit as strategy in itself was closely linked to an observational roaming - around a place looking for what speaks to me as an artist and which become material for work. Here, I found digital trash. And the act of sleeping alone, on the dirty carpets of the former duty free store, made me awake to a strange and somewhat spooky by yet acute awareness of transitional space. I filmed these spaces, which later became a short film, Obvious Threat, which uses the idea of an abandoned airport as material. A film about searching, dislocation, and the elusiveness of identity, hoverin in some unknown time and seen through an unidentified observer (shown at Simultan Festival, Romania (2017) as part of Talking to Strangers section).

Perhaps in contrast, please wait behind the red line (2011/2021) functions on 2 levels. One is about distilling found components into much smaller gesture: the artist book as an object in itself. The other is setting the seeds for making a new work from this material that both considers an aspect of time and duration (2001/2011/2021) as one strategy in making this new work - which also becomes a way to re-envision and fictionalize the archive as a set images from the future. And by doing so, excluding its real-life documentary identity. By taking a found CD with thousands of extremely low res ID images from 1997-2004 as well other materials (Quicktimes, VHS tapes), all found in the same heap of garbage during my site-visit. This exposition, though, is an attempt to both write about process and create new work; a project which touches on ideas of the “poor” image, reflections on image production, the photographic portrait as well as security and identification imagery, and notions of cultural speed and that of being rooted/uprooted seen through the lens of our current covid times. The exposition was started in early 2020, right before the pandemic hit, but albeit time passing it has found it self with new relevance within a post-covid lockdown and lack of travel.

I have also been drawn to the idea of expanding what an archive can be. I am, in parallel to please wait behind the red line (2011/2021) initiating a project where the land become the archive. The environment-as-document. Something from the real world. Bits and codes to collect and re-think and re-form into a work. Like please wait behind the red line (2011/2021) it is a way to process both the mundane and the more magical aspects of a human landscape. I am interested to have elements of poetry and undecipherable codes, a sense that the archive I pull from is somewhere in the borderland of the real and the myth, a more dystopian universe perhaps, without precise temporal organization. I explore methods of abstraction and fragmentation. The strategy to try to see what is already in the world that we are not engaging with, or thinking about, or making use of, or paying attention to. To look for things I haven’t noticed before. I some ways it is a notion of expanded documentary that I explore. Or perhaps something that lies closer to documentary art but as I write this it strikes me as less interesting to start putting labels on a practice. I utilize the real world as material. Using document instead of documentary creates an opening for me to look beyond the associations to the documentary through filmmaking and photography traditions. I have broken with those traditions many years ago but still retain this one persistent and anchored foot in the real world. Etymologically speaking, a document is defined as something that serves to instruct. It may be a text, an image, an object either found or constructed that is used for purposes of identification, education, evidence or archival record. So, bits and stories from images found on an old CD become the document which, in turn, become the foundation for the artistic response, translated into an artist book and investigated through a non-linear presentation.

I need the real world to give me stories or ideas. The filmmaker Jem Cohen once spoke about not needing to make up new stories but to “point to the countless stories that are already in front of us”. I observe that reality is there as material, for me to stroke and re-think and see what else it tells me. Discarded objects transmute into something filled with "hope and fantasy."* New ways of perceiving space are explored. To circle around questions of image, inscription, history, and artifact. Part of my investigation in to making an artist book out the CIA images is to put myself in the role of an editor. Or as an imagemaker viewing someone else new work. I make decisions both as photographer (types of portraits I find interesting) and as an artist (combining several archives to crate a new whole). I take away images of people smiling. Or where there is a clear tendency for the identification portraits, in this new distilled and excavated form, to stand out as looking odd or somewhat deranged. Or simply dull and repetitive. But the historical connection to the mug shot and to the forensic photograph is there, present and fascinating as well as setting up a fine line in terms of how to navigate this sensitive historical notion. French photographer Alphonse Bertillon was the first to realize that photographs were futile for identification if they were not standardized by using the same lighting, scale and angles. But some people believe that Bertillon's methods were influenced by crude Darwinian ideas and that that many of the stereotype looks of criminals in movies, books and comics come from this system. As a way to further maneuver the potential connotations that the images have when extracted as single portraits I have approached the CIA images twofold. One is to create a poster like amalgam of a lesser edit of the original 2977 images but never less an intervention. Second, I intervene even more radically into the Archive to make the artist book where only a handful of images are used, therefore taking them further out of its original context. By combining and juxtaposing them with personal work (2 other archives of portraits and forensic-like abstracts), older family imagery pulled from the same CD, text bits, as well as VHS tapes of educational security films. These were visually translated and transferred from PAL VHS deck found along side the same heap of electronic trash, onto a NTSC camera on the spot with added layers of digital distortion and pixel confusion that is the byproduct of a “wrong” transmission transfer - so prevalent in pre-HD digital video contexts. The geographical war-of-formats in those days would often enhance the digital divide with strict format and pixel dimensions often putting a barrier on creativity. Here, I am using this “mistake” as a part of my process. Further, using the of aspect of close up faces and sometimes subtle, semi-expressive portraits in combination with juxtaposing abstract imagery, welcomed a further Kuleshov reading. New layers and readings are made possible from the interaction of images. Sheets in the artistbook (a box) are loose and single and I am interested in what Lina Selander calls “performative editing”, where in her case hands are filmed sorting through images. For this artist book, the self-structural montage is the performativity. The book can be seen as single sheets or multiples laid out on a table. It further experiments with non-linearity in a publishing form and explores how images can be situated between the photo and the moving image.

The title please wait behind the red line refers to both waiting that is forced upon us in security situations (travel, passing borders) as well as the body placement in a photographic portrait situation. It has also taken on a new meaning in our COVID-19 world as we navigate social distancing with an increasing amount of markers on floors indicating that we cant get to close to each other.

I have thought of myself as mainly a filmmaker but have increasingly, in the past few years, entered a stage in my practice where my approach is more interdisciplinary. I feel steeped in process, of re-thinking and of reformulations. My previous multiscreen installation were both experiments with a more spatial essay form and as a way to work with cinema in a deeper and more complex way. In a more formal and contextually way I have been “bothered by the fact that things are scattered” * Where the things are the pieces in a practice that are differentiated, not connected, separated rather than a mode that bridges methods and disciplines (film, photography, sound). In the 90’s I roamed the streets with my camera, fully immersed in the belief of the existential existence of a flanuer. The loneliness in the metropolitan environment (me and the camera ) was hard to handle though. I enjoyed the psychogeographic roaming but unsatisfied with the results. I gave it up. Or it gave up on me. I see now that part of the reason was that I was left with only the photographs. The snippets of something much more complex. Only part of the dance. The distilling of urban time into a single moment can easily be argued to be the core reason for such photograph. But I still I didn’t have the capacity back then to reclaim the observation into a larger more researched context. The images stayed as single photographs.

I come back to the act of combining when thinking about the artist book one (of many) modes of representing the archive. Similar to the act of combining disciplines in an installation form - materials, observations, walks, research, I am here exploring the merging of several archives to experiment with an abstraction strategy for associative narrative. My increasingly interdisciplinary practice has for many years revolved around the moving image in different installation contexts where a common denominator has been an exploration and experimentation of film language within installation work (cinematic space): multiscreen work, intervals, duration (film time), cinematic reverberations, site specificity, silence and a spatial, non-linear and abstracted contrapuntal montage strategies. In certain ways my work how time be further explored where it can be understood as a kind of accumulation, rather than a linear progression. How film can articulate space, both in an architectural sense as well as becoming environment in itself. Part of my interest has been in exploring how spatiotemporal dimension can contain different medias, components and narratives, which converge and interrelate with one another, opening it up to an alternative direction of what cinema can be. Meta-montage strategies. Similarly, the artist book can be seen a cinematic gesture. And even Research Catalogue itself, as a publishing platform, where multiple strategies of information presentation, layout structures and juxtapositions can be translated into a cinematic montage context. The editing intervention into the 2977 JPGS is not unlike any editing but I was ultimately interested in taking them out of context and give them a sense of uncertainty. Which mages become strong on their own? That go beyond speaking about a face and style of the time and says something else? Can a less than a minute photographic snapshots - with a single frame outcome - produce something that has another type of photographic value beyond the epehemeral? Which speaks about humanity and emotion? Gaze. And what are the narratives that start to appear once other images are introduced?

I experimented with intervening more in the images and digitally altering them further after the fact (B/W, effects to counter the lo-res look) but found that the visible lo-res quality is what gives them context and a sort-of beauty. In many ways they become a sort of essence of digital material. The power of a photographic speed of production embedded in their history and cusp between the analog and the digital. The exaggeration of the pixels fixed in the images and not conjured of after the fact as a simulation. The rawness, ultimately, create a beauty in themselves. A connection of the highly articulated pixels with the grain of analog film and its extension, the fiber print. It is a similar exhilaration I get from analog prints, different printed matters, video projection light. The sense of materiality and image production which I (still) love and am intrigued by.

At the end, a exposition as a layered reflection of both an artistic process as well a way to explore and deepen my thinking around an array of found images. How to situate them as both (anonymous) historic digital images and as continuous material for new readings. And new work.

Peter Norrman

Expanding the Archive:

An artist book as a cinematic gesture - or time as a strategy to revisit older work.

I find myself stripping my photographs of the Mexican mythological night into less and less information. I am supposed to be shooting more classic documentary work; people and portraits and scenery but fall in love with the almost nonexistent yellow street light, the barely lit corners of evenings and the nights. People who I meet and create deep connections with on a human level become fragments in my photographs, separated and only hinting at the real situation, an exploration of the minimalism of the night landscape where there is a presence of people but not necessarily seen. It’s a poetic void. My images become about what we don’t see, what’s outside of the frame, what just happened right before and after. The negative space. The moment(s) right before the moment. Or after. I am younger and shooting these human landscape poems from the heart. It’s the only work that still resonates with me from that period. It’s about fragility and space and abstractions and reacting to the subtle atmospheric light. A clue or a suggestion of something beyond the constrained photographic frame and time device. Now, much later, I can see that I was already shooting a variation of expanded photographic time, wanting a viewer to stay longer within the images, disconnecting myself from the notion of traditional documentary work. I was creating fine art docu-poetry in disguise. Hiding under the pretense of the great loud male photographers but really only wanting to make quiet work. Stripping away information with images that almost start to break apart, each piece needing one another other and asking to be sequenced to be read correctly.

I see now that it was a way of translating my wish for movement.

(text from Konstfack MFA theses)

Exhibitions Curator for Terminal Convention 2011 was Peter Gorschlüter (Deputy Director of MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt am Main).

Participating artists were: Rosa Barba, Juan Cruz, Ross Dalziel (Sound Network), Douglas Gordon, Diane Guyot, Michael Hannon, Martin Healy, Nevan Lahart, Shane Munro, Seamus Nolan, Peter Norrman, Jacqueline Passmore, Le Pavillon (Palais de Tokyo/Paris), Hannah Pierce, Frederic Pradeau, Becky Shaw, Imogen Stidworthy, Paul Sullivan, Padraig Timoney and Adrian Williams.

The exhibition proposition:

“Airports today are among the most controlled places in the world, and the most vulnerable too, not only in terms of security, but also, and more importantly, with regard to human relations, retail strategies and global economies. In 2006 the former Cork International Airport Terminal was decommissioned. A site that saw thousands of passengers passing through arrival and departure halls, duty free shops and customs controls every day until a few hours earlier, finally closed its doors for the last time.

Now, reopened for a few days after years of abandonment in which the site has preserved the traces of its past and has assumed a personal, almost humanlike identity, flickering technology and infrastructure, personal goods and permanently lost property, airport diaries and broken display cases are being reactivated to unfold new life through the interventions and works by over twenty international artists. Turning decay and absence into prospect and presence, the exhibition wakens the decommissioned terminal building to become, for a short moment in time, both an autonomous place and a place where autonomy is negotiated. Intangible to a great extent, the new commissions manifest themselves in the air, in sound, through light or in economic and interpersonal transactions. At first sight almost imperceptibly – a slight pressure in the air, flickering neon lights, LED screens continuously churning out undecipherable messages, conflicting announcements repeatedly played through the airport’s PA system, a 70mm film projector projecting through a smashed window onto the runway, a phone ringing all of a sudden at some abandoned counter, and a duty free shop offering almost every video work an artist has ever made, to name just a few of the multifaceted departure points – this singular exhibition aims to challenge our perception and imagination.”

Sarah Krassnoff was an American grandmother, who over a period of six months in 1970 crossed the Atlantic in 167 consecutive flights with her grandson to elude the pursuit of the child's father and psychiatrist. They traveled New York to Amsterdam, Amsterdam to New York, never once leaving the airport. After a non-stop chase that lasted nearly half a year, Krassnoff finally died of jet lag. In his book “The Third Window” Paul Virilio cites this event, and calls Sarah Krassnoff “a contemporary heroine who lived in deferred time.”

Velocity' is the key word of Paul Virilio's thinking, the post-modern treasure, and the modern society capital. Reality is no longer defined by time and space, but in a virtual world, in which technology allows the existence of the paradox of being everywhere at the same time while being nowhere at all. The loss of the site, city, and nation in favor of globalization implies also the loss of rights and of democracy, as these are contrary to the immediate and instantaneous nature of information. In Paul Virilio's view, Marshall McLuhan's global village is nothing but a 'World Ghetto'.

Or, the owner of the hair salon in my studio building, running after me, wondering why I am photographing what she is interpreting as her vehicle. Was there something with her car? I saw your leaning in and photographing under my car. There has been some oil spill before… Is that what…? I tell her no, I am an artist, I have no reason to photograph her imagined oil spill. I was only looking at puddles and reflections. I feel myself getting annoyed, angered. Projections run both ways and my own paranoia is present as well, thinking I could be a person to try to convey the complexities of this shift in locality. But the cracks and dissolves made me change directions. I continue to roam the streets for image-making or object-collecting despite my complicated relationship to this very photographic street dance I once gave up out of an existential feeling of not wanting to be the other. The quick observer. The one that takes and never gives back. The confrontation that creates suspicion.

"Nothing could be worse than a return to normality. Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world”.

(Arundhati Roy: The pandemic is a portal, Financial Times, 2020)

RADIKALFARM [RF] is a place located north of Stockholm. It is both a physical location and an idea: we are experimenting with living simply, growing our own food and making art.

"Radical for me has to do with returning to something that is very basic. From the term itself, the movement is that of going back to the unseen root, of stripping down to the very basic and changing there."

Trinh Minh-ha

At some point in 2013 I find myself in Washington DC, or more specifically at the National Archives headquarters to do research for a multimedia play I am designing the video for. The play itself is slightly pompous, with three dead dictators convening in an afterlife. I am at NARA to do visual research on Hitler. It’s emotionally heavy, taking in all the hours of this deranged man with a focus on his theatricality to project power. But after some time, I find myself getting numb, more attuned to the presence of being in this very specific archive, a powerful sensation of being in the middle of history. I go from archivist to ethnographer to artist and simply want to spend more time. The idea of not having any pre-conceived notion, no research idea, or concept strikes me as immensely alluring. To simply let the archive and my finds to steer me into a project or some hidden story to use as a seed. The 16mm reels, never digitized, still deep in the NARA vaults, become my dig. It’s old school, with text slips and long waits for the reels to appear. An old Steenbeck become my viewing world. A tiny text fragment with a possible Nazi link leads me to something fully different, a world of documentation that is vaulted and unknown, a state of suspension. To be a witness to a silent encounter and where the unknown cinema is there both as memory and a dialog of continuation. In my head, I propose an artistic residency at NARA, geared towards the experimental filmmaker but open in its form, and not like existing ones geared towards text research and outlined projects.

Two weeks.

From the multimedia theater work JET LAG in collaboration with The Builders Association and Diller, Scofidio + Renfro two true stories from the early 1970¹s intersect that feature characters severed from conventions of time and space. Sarah Krasnoff is the American grandmother who, in a period of six months, flew back and forth across the Atlantic between New York and Amsterdam 167 times with her young grandson to elude the pursuit of the boy¹s father and psychiatrist. During this non–stop high–speed chase, they never left the space of air travel. Krassnoff finally died of jet lag. Donald Crowhurst was a British eccentric who joined the round–the–world solo yacht race sponsored by the Sunday Times of London. Ill–prepared but driven by the guaranteed publicity of the event, Crowhurst loaded up film equipment provided by the BBC to record his journey and set sail. Realizing his inability to make the circumnavigation, Crowhurst broadcast false radio positions of daily progress and documented a successful voyage on film while drifting in circles on the open sea for six months.