Interpretative choices in Brahms' op. 118

- by Håkon Austbø

Having reflected on structural questions in the Six Piano Pieces op.118 since I first learnt them in 1971 (no. 6 in 1968), I soon discovered some of the consequences that these reflections would have for my interpretation. The pieces are often considered rather inoffensive small album-leaves to be performed within the realm of Hausmusik. I wanted to challenge that view since I thought they were conceived as a larger unity with a broad range of expression, touching on profound, existential questions [1]. This might have to do with the fact that I started my quest with no. 6, the E flat minor Intermezzo. This piece, and in particular its haunting middle section, expresses a more profound sorrow and anxiety than any other piece of music I know (with the possible exception of Janáček’s In the Mist). It was, then, rather logical to seek a relationship of the other pieces to this extremely pessimistic conclusion.

So the first reflections were of a psychological nature, but soon I discovered more and more of the motivic relations shown in ex. 2. When I prepared a paper on the set for Joseph Bloch’s piano repertory class at the Juilliard School in 1971, much of this analysis was already in place, even though new insights were added with time, through frequent performances and, later, through teaching.

The first crucial choice was that of the opening Intermezzo. The basic question here is: Do we have a four-note theme or a presentation of two different motifs? For the reader of the above article, it will be clear that I adhere to the second view. But many performers will make an effort to establish the first reading, against the odds since the scoring is contrary to it; the E comes in another voice and a different register from the three preceding octaves of the theme. I was actually one of those performers, as can be heard from the first excerpt of my 1979 recording. Listening to that recording today, I must admit it sounds rather square, partly due to the effort of binding the two motifs together and making the accompanying voice of equal importance. The reader is invited to compare this to the opening as performed in 2013 (BrahmsStavanger at 00.09). Here I phrase the three-note motif a1 and attack the octave E (b motif) in a more articulated manner, while playing the accompanying voice in quavers more flexibly. The latter is, as always in Brahms, a melodic voice in its own right but still secondary to the presentation of the two motifs. See ex. 6, top line.

After the double bar, the same motifs are heard in contrary motion in the two voices (see the bottom line of ex. 6). Does the top C in bar 12 relate to the voice noted as top voice in the previous bar (stems up), but appearing inside the octaves of the other voice, or does it, on the contrary, come from this other voice? The last option is the more obvious, but may not be the intended one. On the other hand, the octave A in bar 12, played with the left hand, has a sforzato and could be the one related to the previous ‘top’ voice, where the actual motif a was heard, whereas the one in octaves is a chromaticised inversion. Four bars later the voicing is reversed.

It seems an impossible choice, and the solution might be that the two motifs are indeed to be considered separate. Again, a clear difference is to be heard between the two recordings. In the late recording (at 0’44), the chord is clearly articulated, the left hand slightly more accentuated, and the inner voice in bar 11 more audible. In the early one, I was still sticking to the standard choice: to bring out G-G#-A-C as the main melody. There had been some reflection going on here in the 34 years between the two performances and, to my mind, a definite improvement.

Comparable problems of voicing are abundant in all the pieces. The most striking ones are in no. 4, described in the above article as a double canon. The ’79 recording (at 2’32) shows that I was already aware of this. Compared to the 2013 recording (at 11’22) there is not so much difference, except for a slightly different rubato, but since the latter is recorded live in a concert hall, the sound is slightly less direct. The pedalling is essential for making heard the canon between the dotted crotchets (see Ex. 3a). In the middle part of the piece, this becomes crucial to the whole texture. Many pianists, of whom a couple are heard in the seminar, make the pedal last for two bars, instead of obeying the change every bar prescribed by Brahms (see ex. 3c).

The last part of the Intermezzo in F minor is a pianistic challenge, certainly in view of the canon that goes on until the end (see ex. 3d). It is important here to get the second voice to sound. From bar 99, the opening of the piece is reiterated but in a thicker setting with crossing of the hands. The dotted crotchets in both voices still have to be brought out, which requires strength in the fifth finger of the right hand crossing over. From bar 111 (repeated in bar 119), we get another setting of this canon, with both voices in the right hand. It is still the same canon of motif b, although for practical reasons not in dotted but in plain crotchets. Finally, the ending (ex. 3e) brings precipitated statements of the inverted a2 motif that has been liquidated in the four previous bars, and the setting requires an unorthodox fingering, indicated by Brahms. The four last chords are, of course, also in canon, with the C’s as main notes.

These examples should suffice to show that the understanding of the musical text and its structural characteristics will have an impact on the performance. Therefore the excerpts from my ’79 recording contain only nos. 1 and 4. But I will mention some other examples as well.

The polyphonic character of no. 2, the Intermezzo in A major, is obvious at a first glance. Ex. 7 shows some of its most characteristic examples of advanced contrapuntal techniques:

Imitation is used frequently, as in bar 7 (ex.7a), and more and more so as the piece evolves. In bar 30 (ex. 7b), the theme is repeated in the bass whereas the soprano’s descending line reflects motif a as heard in no. 1. In bar 34, the inverted theme appears with an immediate imitation in the second voice of the right hand. The theme of the middle part (motif c) is presented in canon of the first four notes (ex. 7c), and the passage in major that follows (più lento) is a complete canon in 4/4 metre, whose musical primacy over the notation in 3/4 should be made clear. The restatement of the same theme (Tempo I) is an inverted counterpoint of bar 49.

Awareness of these contrapuntal procedures is crucial to a satisfactory rendering of the piece and therefore to its expressive power. It goes without saying that this kind of writing by far exceeds the scope of a decorative miniature played in the family lounge.

The transition from no. 3 into no. 4 has been mentioned in the analysis. It is important that the last two bars of the Ballade be played without pedal and that the triad left sounding in the right hand is heard in connection with the first bar of the next Intermezzo: there, the triad is transposed a whole step down, a solitary incarnation of the descending line that I consider the Grundgestalt of the work.

The double recapitulation of the Romanze has also been mentioned. When two voices are of equal importance, the lower one needs special attention since the ear is accustomed to listening to a higher voice. Therefore, when the two voices change place in bar 9, the descending voice, appearing this time inside the octaves of the new top voice of the inverted counterpoint, must be brought out. Balancing out the two voices is the obvious challenge here.

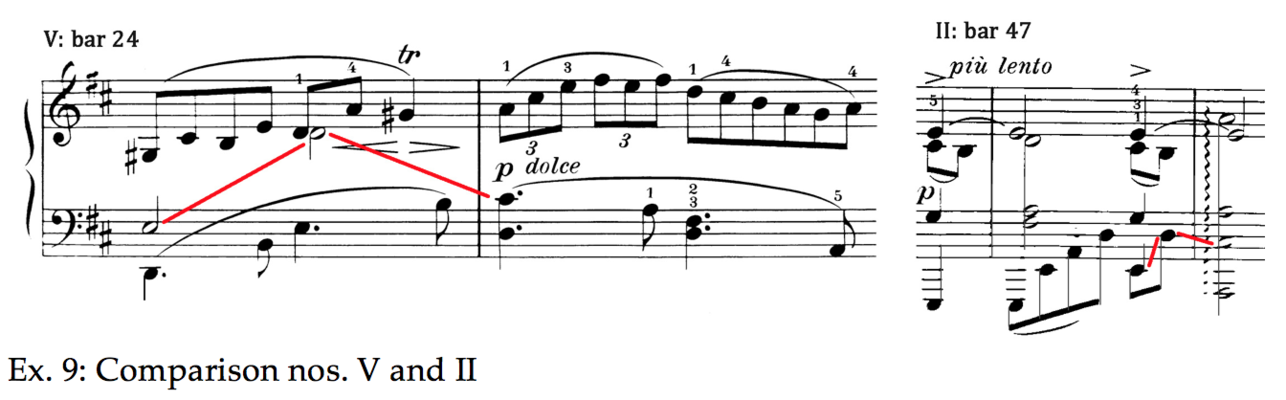

I already discussed the connection between the tenor in bar 24 of the same piece and the disturbingly dissonant C sharp arrival in the next bar, with the same figure in no. 2, here as a result of a retrograded mirror between alto and tenor:

Without such an understanding, the C sharp sounds decidedly strange and incomprehensible within the otherwise mild atmosphere. One is inclined to conceal it, but that would be to deny the musical facts. It is as though Brahms is playing a game with his performer: Guess what this is! Bringing out the voice at the place in question in no. 2 can possibly make the listener aware of the connection, although it takes a very attentive listener to recognise it when it comes back (at 15’47).

The last point to mention here concerns the theme of no. 6. It ends with the three descending notes of the beginning of the first piece, but in the minor. An awareness of this can’t fail to have an impact on the performance. Brahms puts a swell right at that spot:

The F in the beginning of the third bar then takes its full importance, and the whole theme falls into place, as do many things in this work when they are approached analytically. Some enigmas will persist, though. They might be no less than the enigmas of life and death, to which Brahms will return in his op. 121.

See also About Quality [back]

Related article: Brahms' 6 piano pieces, op. 118