Choices and Doubt in Performing Arnold Schoenberg's "Drei Klavierstücke" Op. 11, no 2

- by Darla Crispin

This sub-project of The Reflective Musician explored the idea of ‘unfinished performance’ through considering the problem of doubt and its relationship to the making of choices. Doubt is something with which all performers live but it is usually disguised and refuted in performance; the performer is expected to deliver an interpretation with seamless conviction, whether or not every audience member finds it wholly convincing. But this is not to say that there might not be a legitimate mode of performance that not only embraces doubt but also lays it bare in performance. Indeed, challenging repertoire such as that of the Second Viennese School may be more ‘truthfully’ served by such an approach to performance. In what follows, aspects of Schoenberg’s Drei Klavierstücke Op. 11, Nr. 2, are considered with respect to these issues.

In some concert situations, the desire for more communicative and participatory decision-making may not appear relevant; certain repertoires favour a more straightforward approach and do not evoke any obvious trace of the spectre of doubt. However, this is not the case with compositions of the Second Viennese School. These works are problematic in their essential nature, and their resistance to straightforward interpretation prompts us to look more closely at the necessary performance dilemmas that may arise through a scrutiny of their many layers. This, in turn, raises issues of the role of study in performance preparation and that of curation in performance presentation. Instead of being a potential deterrent to performance, the problematic nature of these works can become an invitation to creative experimentation.

Of all the aspects that may become part of this process of creative experimentation, tempo is one of the more obvious. In the performance of works of the Western art canon, the choice of tempo is one of those elements where the decision-making authority of the performer may be foregrounded, unlike the parameters of pitch or duration in which, outside stylistically sanctioned techniques such as portamento or rubato, departures from the notated score are generally associated with error. The tempo determination for a performance usually has elements of elasticity, even where a metronomic indication is given at the heading of the score. Nonetheless, attitudes to tempo have a pattern, and generally lead to one of three choices, each with specific demands:

Compliance: Where specific tempo instructions are given by the composer, the general approach is to work towards developing a performance that complies with them. In cases of virtuoso repertoire having a rapid tempo indication, this act of compliance is part and parcel of the desired outcome of speed and velocity (in which mastery offers the paradoxical vision of freedom). Where no specific metronome markings are given, compliance takes on a different character, arising from clues in the score, the nature of the notation, generic implications, and other such elements. Overall, this approach of compliance may be associated with Werktreue, and the desire to realize the implications of the composer’s score in a ‘faithful’ way.

Negotiation: The advent of performance studies and, in particular, the close scrutiny of recordings that has resulted (through such bodies as the AHRC Research Centre for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music: CHARM, for example) makes the compliance model less than straightforward, and suggests that the information of the paper score alone may be insufficient in providing data for definitive tempo determinations. Research on recordings repeatedly demonstrates that even when a composer performs his/her own works, there is often divergence from the instructions of the score – the supposedly inviolable compositional instructions. This phenomenon is so prevalent that it considerably loosens the grip of written tempo indications. Related to this are the assertions of the historically-informed performance community, which demonstrate that our contemporary sense of what tempo should be may not be in keeping with past practices, even though tempo compliance (or compliance with the traditions of tempo choice) remains entrenched in the model of ‘faithful performance’ that is still held to be the desirable norm in the academy. Compliance becomes negotiation simply because the performer must choose, from among an array of possible textual and contextual injunctions, which are to be prioritised and how they should interact.

Resistance and disobedience: But there is another possibility for performers regarding tempo, and that is to deliberately depart from prescription in order to reveal some other aspect of a musical work than might generally be perceived (a case in point being Glenn Gould’s epically slow performance of Brahms’ D minor Piano Concerto with Leonard Bernstein conducting). These divergences are usually controversial, precisely because they draw attention back to the performer and away from the work - as if the two are separate, rather than unified within a collaborative system of artistic creation. But, is there a desirable aspect to such resistance - something beyond the highlighting of the performer as an autonomous being - that may, in fact, turn us back to the musical work, and to aspects of that work that lie undiscovered because of the compliance model? Do resistant readings have the potential to uncover aspects of the work that might otherwise remain hidden: what might be called the temporal layers within the work?

The notion of layers of time finds a metaphor in archaeological digs, where the artefacts of a living history may be found in the strata of the ground being excavated. In this metaphor, the deepest stratum is the genesis of the work, and its performance history is built up in layers above that, each performer participating in the creation of new layers. Focusing upon one element can open up an array of associated questions – vertically through the layers and horizontally in terms of other elements found in the same layer.

In the case of Op. 11, No. 2, the apparently simple question of tempo for this piece opens up a vista of ideas. Some of these are noted in the music theory literature, although, as Ethan Haimo points out, analytical work on Op. 11 No. 2 is less abundant than that for Op. 11 No. 1 (Haimo 2006, 316). But of particular interest are accounts of the work’s preparation for early performances, and of the process of re-working that is apparent, first of all, in the 1924 revision, and then most dramatically in the American edition of 1942. What is required is to read the analyses and historical accounts from a standpoint that considers the real-time consequences for performance and reception, and then to consider how this might prompt us to respond. As we shall see, it is actually the performer who becomes the agent of variable readings by virtue of the fact that she enacts the real-time performance that has the potential to uncover the element of tempo pliability.

In Op. 11, No 2, tempo choice arguably determines the piece’s aural identity, and to a particularly high degree. The entire opus belongs to the set of compositions that Schoenberg apparently conceived and wrote down in a white heat of creativity, with little evident sketching or alteration of the musical material once set down (the monodrama, Erwartung, is another example of a Schoenberg composition written in a short space of time). But the three pieces of Op. 11 were not composed all at once:

The manuscripts for Op. 11, like those for the George cycle, suggest that Schoenberg’s compositional method in the early atonal style relied primarily upon a fluid and momentary inspiration. There is little evidence of the extensive sketching that was so pronounced in his work on the Second String Quartet and Chamber Symphony. There are no independent sketches at all for the Three Piano Pieces, and the manuscripts leave the impression that Schoenberg composed the first full drafts quickly and with few interruptions. He dated the conclusion of the first piece 19 February 1909 and the beginning of the second 22 February 1909; the third was composed months later in Steinakirchen am Forst – its draft is dated 7 August 1909 at the end (Simms 2000, 60).

So, on the face of it, the autograph gives few clues that may not be found in the edited scores that come to us. But we may be led to reconsider, even when such a work is written down ‘whole and entire’. How this reflects a notion of the ‘unity of musical space’ (Schoenberg 1975, 223) may be regarded as integral to Schoenberg’s over-arching compositional project. Adorno claims that where this unity is most evident, there is a material vitality that other modes of composition (such as twelve-tone composition, with its particular process of pre-conceiving material) tend to lack:

The sudden transition from musical dynamics to statics – the dynamics of musical structure (not simply a change in the degree of intensity) which naturally continues to recognize crescendo and decrescendo – explains the uniquely determined systematic character which Schoenberg’s compositional technique assumed in its later phase, as a result of the twelve-tone technique. The tool of compositional dynamics – the procedure of variation – becomes absolute. In assuming this position variation frees itself from any dependence upon dynamics. The musical phenomenon no longer presents itself involved in its own self-development. The working out of the thematic materials is reduced to the level of a preliminary study to the composer (Adorno 1973, 60-61).

Of course, there is a magical, or myth-making, element to all of this, the fulfilment of an apparent desire to witness a holistically expressed ‘inspiration’, and the belief that this should involve the achievement of something extraordinary, without an obviously associated expenditure of effort, or disclosure of a system. We understand Schoenberg to operate in both worlds: the one of rapid, inspired creativity and the other of achievement through hesitancy, hard labour and systematic enquiry. The coincidence of the former with a particular historical moment and a particularly volatile, transforming musical language imbues these works of 1908-1916 with a particularly compelling quality, especially since, in their exemplary natures, they resist definitive analysis, definitive historical description and definitive performance.

At the centre of this array of volatile works of intense expressivity, the performer becomes an exposed agent of communication and thus a purveyor of possible transformation. To be placed in this kind of position is often far from comfortable; the consequences of resistance to the composer’s work are first borne by the performer at the moment of placing the work before an audience (although in accounts of composers, the performer’s stake in this situation is often bypassed, relegating the performer to the role of transmission vessel and downplaying their investment in the presentation of difficult art). Edward Steuermann’s account of performing Op. 11, No. 2 in Regensburg in 1913 shows the performer in this often thankless role; reconciling compliance with Schoenberg’s instructions concerning tempo with his own consciousness of potentially limited audience tolerances placed him in a genuinely vulnerable position:

When did you first play the Op. 11?

In 1911 or 1912, but I played the Op. 19 in public even before then… Later, I remember I played the Op. 11 in Regensburg in a horribly cold and bare “Turnhalle,” and I remember the faces of all those Bierphilister. To play the Op. 11 no. 2 as slowly as Schoenberg wanted for such an audience was quite something in those days! This was in 1913; then the war broke out, and we all went into the Army.

But immediately after the war Schoenberg started the “Society for Private Performances.”…. We had a hierarchy of supervision for performances in our “Verein”: there were three so-called “Vortragsmeister” whose task it was to coach the performers – Webern, Berg and myself, and later Erwin Stein. The highest authority over all of us was, of course, Schoenberg (Steuermann 1989, 174).

It is ironic indeed that the development of performances that were to demonstrate the potential and scope of new music were eventually to be evolved within a restricted society with a quasi-military sense of rank; it seems all too apposite here that Steuermann links this account with that of service in the army. Composers (led by Schoenberg) coached performers who, in turn, performed for audiences whose members were ‘screened’ and who agreed to follow a particular code of receptive etiquette. In a separate account, we learn more about the exchanges between Schoenberg and Steuermann concerning Op. 11, No. 2:

…When [Schoenberg] heard me play the Op. 11 for the first time, he made some slight changes in the first edition. He added some more marcato signs, indications “without pedal,” etc. I remember he wanted the second piece very slow, which was astonishing to me in view of the indication, “Mässige Achtel.” When I had to play these pieces the first time in Regensburg, he gave me this memorable advice: “Don’t be afraid that the audience might become nervous because of the slow tempo. If you believe in your tempo wholeheartedly, the piece will not seem long; if you are unsure of it, it will become boring.” But in the second edition the metronome mark indicates a faster tempo (Steuermann 1989, 182-183).

Steuermann’s ‘astonishment’ at Schoenberg’s tempo request and its contradiction of the written indication is important to note here, as is Schoenberg’s strong, and almost mystically inclined, encouragement to carry out the slow tempo instruction sustained only by inner belief. The ‘boredom’ that performers often fear in relation to slow tempi is actually not attributed by Schoenberg to the tempo itself, but to the inability of the performer to deliver it with conviction. In other words, any boredom of audiences with slow tempi is the responsibility of the performer.

Steuermann was not the only performer to be perplexed by the tempo problem in Op. 11, No. 2. It was clearly an issue for Ferruccio Busoni, whose deep interest in the piece would generate a rich exchange about the nature of composition, performance and transcription. Schoenberg writes to Busoni on 3 July, 1910:

…Your transcription [of Op. 11, no. 2] contains any number of ingenious details which prove how deeply you have penetrated this piece and how sensitively. Some things are wonderful, highly interesting and very precisely thought out. And I must admit:… had I not wished (and been able) to write this piece, then I would have wanted to write yours, your transcription. But I have written mine, and your arrangement has not convinced me that mine is not good. On the contrary, a good but by no means brilliant pianist has made it sound very well. Maybe you have been playing it at a tempo other than that intended. I prescribe: ‘moderate quavers’; yes, moderate quavers. But a moderate quaver is of course faster than a moderate crotchet; because it is, of course a quaver, and otherwise there would be no reason to write quavers. Perhaps this has misled you. Perhaps I should have written: moving quavers (circa MM ♪ = 80-90). That is moderate for quavers, because the value would thus become [dotted crotchet] = 26-30! (Beaumont 1987, 404).

But most performers, and indeed, most listeners, would agree that slow movements generally challenge audience attention more profoundly than fast ones. The slow tempo is a vulnerable tempo. In this case, what is of significance is that Schoenberg appears to regard that vulnerability as integral to what he wishes to say at the particular, historical moment. The components of that ‘saying’ seem to be a composite of his deliberate provocation of his audience and the highly expressive, angst-ridden aspects of the musical material that, as we shall see, become even more strikingly foregrounded in a slow tempo. However, in the case of Op. 11, No. 2, the compositional, performance and editorial histories reveal an even more complex picture:

Evidence compiled by Reinhold Brinkmann suggests that Schoenberg, after deciding to group the three short works into a single collection, wrote out a fair copy that is now lost, probably after being sent to Universal Edition as the Stichvorlage for the first edition, which appeared in October 1910. This was Schoenberg’s first publication by Universal Edition and also the first publication of any of his atonal music. By then the pieces had already been heard publicly, premiered by Marietta Werndorff in a concert of Vienna’s Verein für Kunst und Kultur on 14 January 1910, and Schoenberg had also sent out manuscript copies to other prominent pianists, including Béla Bartók and Ferruccio Busoni, hoping for additional performances.

In revised editions of 1924 and 1942, the composer continued to add refinements to the score, mainly concerning nuances for the performer. In letters to Busoni he emphasized that the works had to be played with pronounced rubato. “I never stay in time!” he wrote. “Never in tempo”. Tempo was indeed a crucial factor in creating the proper effect. Schoenberg urged Edward Steuermann to choose a very slow tempo for the second piece, and he mentioned to Busoni a metronomic rate of 80-90 to the eight note in this movement (Simms 2000, 61).

As noted above, the correspondence with Busoni appears to point up a radicalising agenda to do with the nature of 'modern' music, as both Schoenberg and Busoni were theorising about this at the time. Of more immediate relevance, particularly for performers, is the continuation of Simms’ account of the editorial history of Op. 11, and his observation concerning its 1942 edition:

For an American edition in 1942 he added metronome markings for each piece: the quarter note at 66 in No. 1, eight note at 120 in No. 2 (thus fully 50% faster than the tempo he had mentioned to Busoni), and eighth note at 132 in No. 3 (Simms 2000, 61).

So, Schoenberg’s Op. 11, No. 2 presents a case in which the choice concerning tempo, and the array of contradictory evidence that might underpin that choice, highlights the role of the performer as having both archaeological and curatorial aspects.

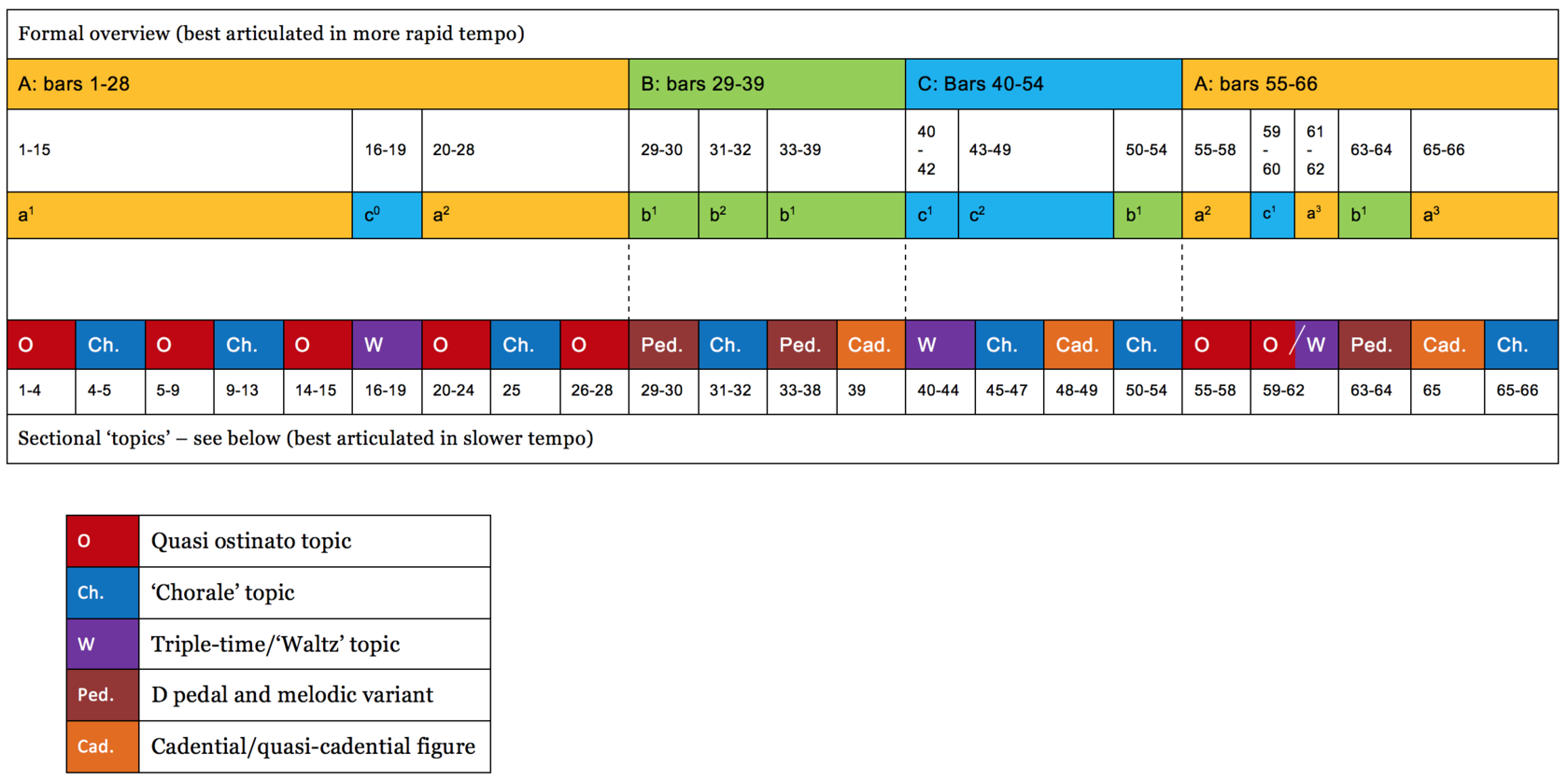

Schoenberg Drei Klavierstücke op.11, no 2: relationship of structural interpretation to tempo adopted

Initially, the slow tempo seems less effective in the quasi-ostinati, being extremely difficult to sustain in performance. Nonetheless, for the Arnold Schoenberg of 1909, this vulnerable moment in performance appears to have something essential about it. As noted above, Schoenberg was clearly conscious of the performance challenge, given his appeal for courage and belief as part of his dialogue with Steuermann; this also shows that Schoenberg regarded the slow tempo as a particular form of audience provocation. But, enmeshed with this desire to provoke, or indeed, concomitant with it, is the drive toward genuine communication; the slow tempo must ‘say’ something to its audience, at least to the audiences of pre-war Europe.

Schoenberg’s apparent change of heart regarding the tempo, as manifested in the 1942 edition, is attributable to a number of factors. Working with the structures of twelve-tone music may have altered his sense of the performative architecture of Op. 11, No.2. He may also have been affected by his new social situation – his American environment – in proposing the new tempo; or, he may have been reacting to past reception. Whatever the case, the tempo revision of 1942 does bring forward a different layer of the performative/aural architecture. Again, the ‘B’ section (Bars 16-19) points this up. The more rapid tempo instruction leads to an aural sense of cohesion; the beat of four within four bars (Quattro battute) melds the section together and the tempo make such structures clearer within the larger architecture.

In a sense, then, Op. 11, No 2 becomes several different pieces within the conceptual space of a single work, mediated by tempo selection. The apparently unified manner of its conception – the quick drafting of the autograph – does not contradict the possibility of manifold readings through using tempo variability as a tool for differentiating architectures in performance. Perhaps Schoenberg is highlighting this possibility in an almost theological sense. “They call him many who is but one”. His emphasis upon compositional unity and the notion that this unity is also inclusive of multitudes is an essential part of his creative approach.

Interestingly, though, it is in the realm of the performer that these aspects are brought to life, through the differentiated aural experiences brought forward in performances heard in real time. Once again, we are left not with solutions, but with a field of approaches requiring informed choices. The performer takes a more vitalized, responsible and communicative role through the negotiation of these performance problems.

Practising musicians are often faced with the issue of tempo divergences and how to make choices when confronted with apparently contradictory information. But the matter of tempo in this case gives rise to a series of more far-reaching possibilities. Musicians today generally work rather carefully to realize prescribed tempi, thanks to the normalization of performance through the widespread use of metronome markings and the reification of the parameter of tempo through its preservation in recordings. This compliance is so pronounced that, as noted above, surveys of tempo divergence in recordings of canonical repertoire are commonplace in both sophisticated scholarship and novice research projects. In the majority of the works of the canon, we have some notion of what we think the tempo should be, although the basis upon which we come to these decisions – such as mainstream performance traditions – may not be as strong as we might wish.

Nevertheless, departure from these norms creates attention. The rationale for such departures ranges from convictions concerning historical performance based upon score research and other research evidence (e.g. Roger Norrington), to a simple desire to experiment with tempo relationships across movements. That such phenomena have tended to be captured in recordings has pointed to the need for a systemic investigation; a set of such investigations was conducted through the AHRC Research Centre for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music (2004-2009), which argued, through five inter-related research projects, that understanding the multiplicity of musical presentation needed to go beyond apprehending its expression in the score in order to include the sound as heard through various media and in a variety of cultural contexts. Such approaches begin to break down fixed notions of the ‘work’, opening up ideas concerning contingency and social situation.

This more open approach to study generates an obvious question with reference to the subject of this chapter: what if divergent tempi truly reveal a single work to be, in fact, a multitude, in the style of a Russian doll? This is the tantalizing prospect that is put before us with Op. 11 No. 2, with Schoenberg’s own instructions to performers serving as the catalyst for such thinking. So, if two tempo choices have the potential to reveal multiplicity within a single work, to what extent might the differences reflect historical changes contemporary with the revised information? What is the world of Schoenberg 1942, as opposed to the world of Schoenberg 1909-1910? Or, does the fact of the change reveal a linkage, rather than a divergence? Can performances actually show these differences or divergences? More radically, can we, the performers of today, develop new ways of presenting the musical material that lay multiplicity bare, exposing the problems of choice, and somehow, either involving listeners in aspects of decision-making or presenting the array of options, without articulating a final choice?

The uncertain tempo of Op. 11 No 2 links into other aspects of how the work is heard and understood. Another question that is often posed with reference to Op. 11 as a body of work is whether its constituent pieces are tonal or not. As Ethan Haimo suggests, there are strong arguments for regarding the first and second pieces as ‘not a break with, but rather an expansion and transformation of, the past’ (Haimo 2006, 317) and thus to regard the musical language as being pulled between past and present. But why mightn’t we regard the bond as broken, and the tonal sounds as non-functional remembrances? In performance, this can be an effective communicative approach. It would also appear to have resonances with Schoenberg’s own concerns about the question of tonality. Obviously, he had an interest in associating his work with the radical, with progress, as we see in the account given by Simms:

But Schoenberg himself was emphatically opposed to theories that found an imperfect expression of key still at work in his music beginning with the George songs. To Busoni on 24 August 1909 he wrote: “My harmony allows no chords or melodies with tonal implications any more”. In a marginal note that he added to his copy of Nüll’s treatise he wrote: “This book could just as well have been written 25 years ago….Nothing could be more irrelevant than the contrived argument that the ostensibly ‘atonal’ is still ‘tonal’ (Simms 2000, 64).

Schoenberg’s preference in 1909 for a very slow tempo may have a link with his statement above that the music has ‘no chords or melodies with tonal implications’. The detailed hearing facilitated by the slow tempo tends to break down the apprehension of larger sound structures, which is another reason that the execution of such a tempo is difficult for the performer in terms of the communication of coherence. Related to this is the aural reification of musical materials; identities become unstable: the opening ostinato is no longer really an ostinato; a ‘key’ is a remembrance, not a function.

Consideration of the problems that might emerge in standard professional concert life if such alternatives were to be explored brings up the whole problem of how heavily regulated (in terms of performance) our ‘modernist’ repertoire has become. Can we not experiment, even if to do so is to break some customary boundary? ‘Good taste’ is no fair earnest of innovation. To risk the curated performance that provokes some kind of meaningful response is to be made vulnerable. It is, therefore, absolutely necessary.

But we can also go beyond curation – we can redesign. This means, however, to undertake an even more ambitious intervention. It also means transgression, vulnerability and doubt. However, it may be the very actions that emerge from this doubting that generate an art-making that can still speak to us. This response to doubt is not a retreat into fear; it is an advance into a field fertile in fresh questions, and new forms of response.

References:

References:

Adorno, Theodor W. 1973. Philosophy of Modern Music, tr. Anne Mitchell and Wesley Blomster. London: Seabury Press.

Beaumont, Antony, ed. and trans. 1987. Busoni: Selected Letters. (London: Faber and Faber Limited).

Haimo, Ethan. 2006. Schoenberg’s Transformation of Musical Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schoenberg, Arnold. 1975. Style and Idea: Selected Writings of Arnold Schoenberg, ed. Leonard Stein, tr. Leo Black. London and Boston: Faber & Faber.

Simms, Bryan. The Atonal Music of Arnold Schoenberg, 1908-1923. Oxford 2000.

Steuermann, Edward. 1989. The Not Quite Innocent Bystander. Edited by Clara Steuermann,

David Porter, and Gunther Schuller. Translations by Richard Cantwell and Charles Messner. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

The decision about tempo alters the aural architecture of the work, and thus the performance experience (including the receptive aural experience) bringing to the fore contrasting affects according to the choice selected. The instruction for the 1909 performance places the focus upon the groups of three quavers because of the extreme slowness of what Schoenberg requested here. 12/8 time is easily heard as 3/4 x 4, allowing the ghost of the waltz to inhabit a work that, in the context of the ‘long nineteenth century’ may be classed among the fin-de-siècle compositions of Schoenberg. Whether or not to point this up becomes a performance decision; the viability of the approach is most vividly apparent in the ‘b’ and ‘b1’ sections of the piece, where the quasi-ostinato gives way to material that, in the slow tempo, may, indeed, be heard as having waltz characteristics.