Chopin’s Third Ballade - an analytical approach

- by Håkon Austbø

The reasons for dedicating a seminar of The Reflective Musician to Chopin’s Third Ballade, in January 2014, were many: among Chopin’s works it is a particularly rewarding piece to investigate, due to its clear structure and subtle contrasts. It is a widely known piece and often performed, to the better or the worse. I was at the time preparing a recording of the Ballades and other works by Chopin, and my fellow member of our research group, Lasse Thoresen, was preparing a study on interpretations of the piece, notably the one by Rachmaninov. His account on this study will appear elsewhere on this exposition. (Thoresen LINK)

In his book on Chopin, Alan Walker discusses at length the question of the role of analysis for the performer. Here are two key statements from that discussion:

It is the player who makes music live; the more he knows about the way it hangs together, the more successful he will be in his task. [1]

A musical structure contains the answer to the problem of its own interpretation. A great interpretation is never ‘applied’ from without; it always emerges from within. [2]

We can easily take Walker’s statements as mottos for our investigation. That his findings concerning the Third Ballade are almost congruent with my own is a matter of fortunate coincidence, since I only became acquainted with them at a late stage of my own research. [3]

A video from the seminar can be found elsewhere in this exposition; this article will attempt to elaborate on some of the questions raised during the seminar. My own recording of the piece is also available here (-> right column), although it is not meant to offer a definitive response to the questions raised. In fact, after having done the recording, I have come to new insights, which form the beginning of the next turn in the spiral that may be taken as a symbol of our work: how does interpretation lead to new knowledge, new knowledge to fresh interpretation and so on ad infinitum? This is an endless on-going process that makes performing so fascinating, and an approach that differs fundamentally from the more dogmatic studies of performances of the past, however helpful those may be as starting points in their own right.

The Ballade, incarnation of a new style?

A new way of composing

There are indications that the first Ballade, which was published in 1836 but probably commenced some years before, marks a new procedure in Chopin’s composing. Olaf Eggestad touches on this in his essay on the Polonaise-Fantaisie LINK: are the ballads early manifestations of a late style, with the first one as a kind of precursor? What is certain is that, after having composed more or less in accepted idioms, for the first time, Chopin departs from conventional forms and creates totally new ones, dictated by the content. Jim Samson discusses the change of style that took place in the first half of the 1830’s, and concludes:

These stylistic transformations registered a fundamental change in Chopin’s whole approach to composition, a change which may be summarised crudely as an investment in the musical work rather than the musical performance. [4]

This change entailed a departure from certain musical forms intended to please a public, such as the concerto and the variations. The choice of the title Ballade was a novelty when it came to instrumental music and implied a narrative, if not exactly a literary, form. Much has been written about the connection with Polish Romantic poets like Adam Mickiewicz, but these connections are speculative. The narratives here are purely musical and embedded in forms that show a close relationship to sonata form (itself an ur-narrative about tension and resolution) but also display fundamental differences, both of content and style.

Schumann saw this and called the first Ballade “one of his wildest and most original compositions” [5], and, indeed, when we try to superimpose the work on a traditional sonata form scheme, it fails to comply. Instead of returning on the tonic, the second theme reiterates in the same E flat major as before, in an enormous prolongation including the statement of the same theme in A major, emerging in its turn after a developing restatement of the first theme [6]. Instead of a central development we get a waltz-like episode; indeed development occurs throughout the piece, and the coda sums up the process in a turmoil of dramatic statements that seem unrelated to the previous, but, on closer examination, prove to give answers to several unfinished processes witnessed before.

Form is reinvented each time

When, some years later, Chopin returns to the Ballade form, it takes a completely new guise. Known as being in the key of F Major, op. 38 ends in A minor, and the duality between these tonalities is really the ‘story’ of the piece. Schumann testified to have heard Chopin play an earlier version that concluded in F Major and called it the “Ballade in F major/A minor” [7]

. I would rather call it a piece in A minor with a lengthy introduction in F major. The fatal attraction between both tonalities can be described as one of the 6th degree into the dominant, as clearly expressed in the motif that initiates the Presto con fuoco: A-F-E. (See also Fig. 1. F and A are heard simultaneously.) As with the sonata form, the form here also depends on a tonal tension, but somehow in the opposite direction: what is presented as the contrasting tonality here becomes the magnet that pulls the tension into its own black hole. A minor ‘absorbs’ and thereby effaces F Major, rather than being resolved back into it.

The low 6th degree is also the main focus point of the fourth Ballade, although here the situation is far more complex. There is a double conflict here: in the first part, the tonality tends towards B flat (minor or Major) with a disturbing factor in its submediant G flat, whereas the core of the tonal progression happens in the conflict between D flat and C: respectively the submediant and dominant of F minor and already presented in the first theme in the form, a, that I call the generative motif of the piece.

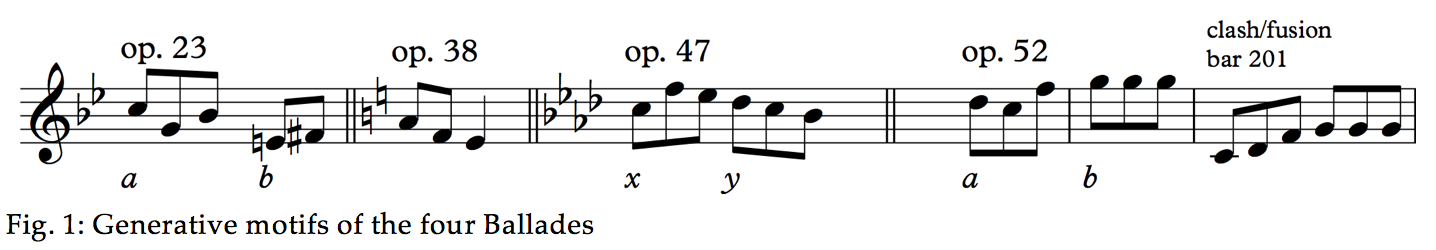

All the Ballades have in common that they lean strongly upon a single motif in which melodic and harmonic material originates. In Fig. 1, I show what I find to be these motifs.

There are secondary motifs as well, designated as b or y respectively. In no. 4, the two are confronted at the moment of maximum tension, as part of the structural cadence in bar 201. (The tonic comes in bar 211).

This is not the place to elaborate extensively on the three other Ballades, but it should suffice to show that there are driving forces shared by all of them, with very similar intervals generating the various materials, namely a fourth and a major or minor second. This Grundgestalt-procedure [8] is well-known in Brahms, but less so when it comes to Chopin, who certainly was subject to the Austro-German influence [9]. As to op. 47, the one we are discussing here, it is driven by the motif x, an arching shape passing at its apex through the sixth degree, also the secondary tonality of the piece (F minor).

Contrapunctal style

Before going into the detail of op. 47, one thing should be mentioned here: the increasingly important role of the counterpoint through the four Ballades. If, in nos 1 and 2, it is still modest, the two last ones show many instances of involved contrapuntal work. It is certain that Chopin at this stage took an increasing interest in Bach (see Eggestad LINK), and especially in the fourth Ballade at places like bars 121 and 135, the influence of the Baroque master is evident. It is interesting to note that both Mozart and Beethoven experienced, at a rather late stage of their creative developments, a similar predilection for counterpoint, combined with studies of Bach.

In the Third Ballade, the contrapuntal presentation of the material is apparent right from bar 1: the four strands of the first theme are heard in the soprano, the tenor, the bass and the soprano respectively.

The A flat Major Ballade: general

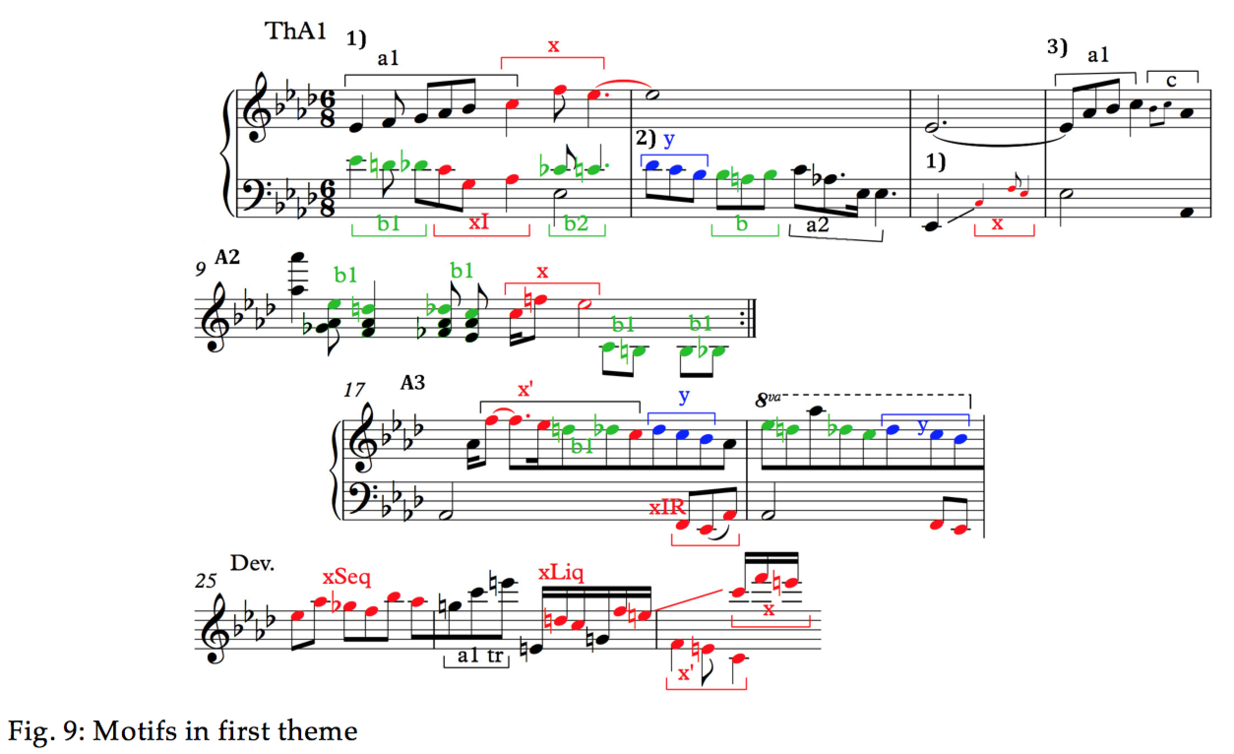

This first theme, shown in the top line of Fig. 2, contains all the essential material of the piece.

In this survey of the motivic developments, I have assigned three different colours to the three main motifs, in descending order of importance, red for the basic motif x, blue for the secondary motif y and green for the auxiliary chromatic material b. We also have the rising scale spanning a sixth that forms the beginning of the theme, called a, and another secondary motif c, derived from y. These are rendered in black.

I shall return to the details of this survey, but my purpose here is simply to establish the fact that the motif x is not only responsible for most of the melodic material of the piece, but also determines the disposition of tonalities. The second theme is first heard in F minor, coming out of an unstable C major, then returning to A flat via E flat, although in bar 103 it touches back on C major on the way. The second time, the theme starts in an unstable A flat major (bar 146) to land on C sharp minor (the enharmonic of D flat, the subdominant), then moving to B natural wanting to go to E, which it finally does in bar 226. Fig. 3 shows this sequential ordering of tonalities.

These progressions create a remarkable unity between melody and harmony which cannot be neglected, and which is confirmed by the bass in the two last bars of the piece: C-F-Eb-Ab, providing a strong conclusion.

Shadows

In the late 19th century, James Huneker described the third Ballade thus:

It is the schoolgirls' delight, who familiarly toy with its demon, seeing only favor and prettiness in its elegant measures. [10]

As a typical description from that period, it doesn’t leave room for the shadows that will dominate the last part of the piece. True, op. 47 is less “tragic” than the other three Ballades, and the darkness emerges only with the turn to C sharp minor in bar 157. The elegance and grace then gives way to something quite different, and the apotheosis of the first theme that crowns the following development, is only an apparent triumph. Alfred Cortot describes it as:

a hymn of distress, intoxicated by its own suffering.. An apotheosis, certainly, but one of suffering and of unappeased desire. [11]

This must be seen in the light of Cortot’s association of the piece with Mickiewicz’ poem L’Ondine, but also on pure musical reasons it seems logical, when one considers the frenzy of the coda.

The dark part somehow engulfs the greater part that precedes it, much like the F major part of the second Ballade is engulfed by the A minor section. The change occurs shortly after the golden section of the piece, which is at the beginning of bar 150 (241x0,618=149). It is improbable that Chopin calculated this; therefore we must assume that he consciously established the relationship of a long and a short section, unconsciously getting close to the golden section. (See Eggestad LINK and Bartok LINK)

Seen in such a way, the fact that even a piece that starts in such a lovely atmosphere ends in tragedy, is symptomatic of an image of Chopin that for a long time was blurred by convention. As Arthur Hedley puts it:

..his music, which contains alongside with softness and charm so much of passion and indeed ferocity, was not the product of the gentle inoffensive creature with whom legend has made the world familiar. There is also in Chopin a note of defiance, of insolence almost, towards the musical conventions of his time.. [12]

Editions

Much can be said about the editions of Chopin’s works through history. Certain is that the freedom taken by many of the editors in the decades following Chopin’s death, has done a lot of harm to the understanding of his texts, and only very recently we have got editions that respect his intentions. Even now, it’s difficult to obtain a reliable edition since Jan Ekier’s national edition (PWM), the most up-to-date one, has recently been available only in pocket score.

Jim Samson discusses this problem thoroughly [13], and concludes that even this edition has shortcomings, due to the multitude of sources that may be considered authentic. The performer should know about the differences between these, and a good edition should give this information without any subjective judgments. He does suspect Ekier of such judgments, but adds:

At the same time he recognises that to identify a single ‘final text’ in Chopin is not always possible, and his incorporation of variants is an explicit acknowledgement that one should rather speak of ‘final texts’. [14]

The proof of this is that even between Ekier’s own edition of the Ballades published by Universal, and the more recent Polish one, there are important differences, especially in the fourth.

For the Third Ballade, the variants don’t present dramatic differences. But earlier editions do. The phrasing of the first theme is one example, and another passage, starting at bar 99, is particularly interesting. Fig. 4 shows both passages in two different editions.

By playing a diminuendo in bar 102 as in the Peters edition, the arrival on C major in the next bar becomes feeble and its structural significance concealed. This kind of modification might be considered symptomatic of the attitude toward Chopin in the late 19th century (see also above, the citation of Hedley), considering him above all aristocratic and elegant, avoiding strong, straightforward statements like that here.

Another noteworthy variance is the rhythm in bar 99: by adding a quaver rest, the Peters edition (and most older editions) destroys the syncopation of the A flat octave. The PWM edition (example below) gives the unsyncopated reading as an ossia, and in further ossia’s the A flat is slurred from bar 99-100, and the C from bar 101-2, like in the Peters. Moreover, the German first edition doesn’t give p in bar 103, which could be a logical consequence of the crescendo that has in fact been going on since bar 95, and which joins nicely with the diminuendo in bars 114-115. All this is one example of the multitude of choices given to the performer who studies the sources.

When I was a student, the Peters edition was the reference, but the Paderewski edition was also available at the time, and Henle started to publish Chopin’s works. Their edition of the Ballades dates from 1976, but has in the meantime been outdated by Ekier and others. This makes it all the more indispensable to make the best recent editions available to students who study Chopin’s works (and they all do), and this is still far from being the case.

When it comes to the phrasing of the first theme (Fig. 4a), I shall return to this when discussing some of the historical recordings. But the correct phrasing, separating the C from F-Eb, doesn’t mean that these three notes don’t hang together motivically. Some scholars consider the F-Eb as being the central motif here [15], and this is plausible, but it does hide some of the connections that I find important in the piece.

Making the structure speak

Indeed: how can you make the structure alive in a performance? This is one of the primary questions of The reflective musician. There are many points in the score of the Third Ballade where choices can be made in this respect, in the detail as well as in relation to the larger picture. Knowing where the harmonically structural points occur is one of the core questions here, the thematic connections is another. I shall return to some of these points after discussing structural issues.

Structure

Sonata Form?

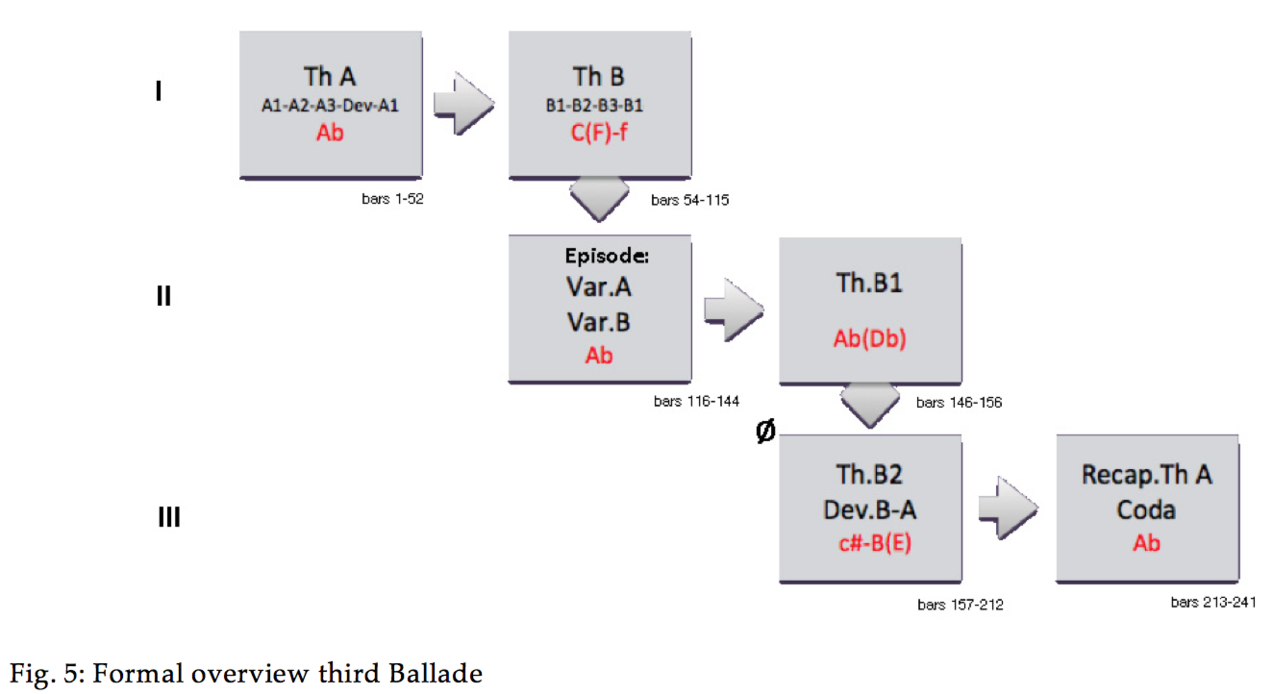

The form of the Third Ballade is certainly derived from the sonata form, but like the three others, it by no means obeys to the prototype of this form as established in the beginning of the 19th century. We have already touched upon the deviations in the first Ballade, and in many respects, the shape here corresponds to that one. But again, Chopin creates a new form emerging from the necessity of the content. The scheme is summarised in Fig. 5:

I have already discussed the sequential tonal scheme (see Fig. 3), except for the initial and final A flat major. In my diagram, the first row represents the exposition of both themes. The third strand of theme B might also be called a local development, similar to the short development inserted between the strands of theme A. The blocks in part II take the place of a development, but they have a quite different function, like the waltz section in the first Ballade. The episode is in a stable A flat major, and it presents new material that can be characterised as variants of both themes. The next block brings back the first strand of theme B in A flat, tending towards D flat, which forms, together with the block beneath it, a complete recapitulation of this theme. We have reached the dark part or the short section of the piece, where the dramatically transformed version of B2 leads directly into the development section that combines both themes and brings the ‘apotheosis’ of theme A and the coda, based on the middle episode.

There are other ways to describe the form of the piece. We can look at it as a lied form with the central episode as a contrasting section, followed by a mirrored recapitulation of both themes of the main section [16]. However, such a disposition wouldn’t account for the dramatic change of character with the turn to C# minor, which clearly announces a new section in the piece. This is precisely what makes the form so ambiguous and therefore so interesting in comparison with a prototypical sonata form. The fact that the middle part (at bar 116) has a tonal stability on the tonic that it shares with the beginning and end sections makes it neither the contrasting part of a lied form nor the development section of a sonata form. What function does it have, then? It introduces a pianistically brilliant character and joyful excitement through the use of semiquavers, after the longing, swaying rhythm of theme B. Tonally, it provides stability after this unstable theme that vacillates between C and F. It also prepares for the reintroduction of the same theme B departing from Ab major which in its turn becomes unstable and moves on to D flat, enharmonically C sharp, reflecting the movement from C to F before.

The factual recapitulation of theme B is therefore on the subdominant, like in some of the Schubert sonatas. However, it doesn’t seem right to let it start already in bar 144, since the reiterated B1 on A flat rather prolongs the section preceding it and joins with previously heard versions of the same theme. This is why I propose a division into three, where the last part represents the negative portion of the golden section (marked with Ø), even if this falls in the middle of theme B.

Cortot proposes the opposite: to let this statement of B1 carry the dark premonition of what is to come:

It would be good to foretell this modification of character already from the first bars, that should be played in a feeling of anxiety and worry, precursor of the dramatic development that soon takes it into its fever. [17]

This reflection shows that one’s reasoning concerning the formal function of a passage can alter the way it is played. I don’t agree with Cortot here, following the argument above, but I do see the point. If one does consider bar 144 to be the start of a development (as Samson and others do), this would be a way to show it. In my opinion, the change comes in bars 155/156, parallel to bars 63/64, where the apparent tonic suddenly becomes a dominant:

Emergent forms survey

I shall discuss some of the details of the form further on, but I would first like to consider an altogether different way of looking at the analysis. Research group member Lasse Thoresen has made a graph of the third Ballade based on aural analysis. It is shown in Fig. 7.

I will refer to this graph in the following discussion, together with the motivic survey, but the symbols here require some explanation, which is given in Fig. 8.

Through surveying the analysis of dynamic forms, the reader will be able to easily observe the form-building contrasts between stable time segments (squares) and unstable passages (triangles). The bold lines added indicate that one of these functions is emphasized.

The small angles in the lowest lines of the piece with letters represent Thoresen’s segmentation of the piece. The formal divides correspond more or less to my own, except for the episode, which is here named Y.

In addition, Fig. 7 displays symbols referring to an aural evaluation of harmonic luminosity, i.e. brighter vs. darker tonalities, the paradigmatic example of which would be the contrast between major (brighter) and minor (darker) which also represents a move of three fifths to the left in the circle of fifths. This paradigm is extended in different ways. So when an A flat is exposed with an E flat on top, a C Major with an E natural on top would then appear brighter since the E flat to E natural suggests the movement from minor to major, and represents a modulation 4 fifths towards right in the circle of fifths. The upper line of Fig. 7 displays this interpretation by means of circles and arrows: An arrow pointing to a white circle indicates a movement towards a much brighter tonality; an arrow towards a fully shaded circle a movement towards much darker tonalities, and half-filled circles suggest an intermediary position. The darkest tonality occurs in bar 157 (Fig. 7), where the piece modulates to the minor IV of A flat major (enharmonically notated as C#); here the major IV is turned into minor, and as a result the modulation represents 4 fifths to the left in the circle of fifths. Moreover, the low register of this section underpins the dark harmonic luminosity. Relative to this tonality the final A flat major (bar 213) represents a maximum luminosity (four steps to the right in the circle of fifths).

Moreover, Fig. 7 presents an aural analysis of the rhythmic flow and friction in the music represented by arrows: Arrows pointing to the left represent friction; arrows pointing to the left represent flow; the more lines on the arrow the stronger the characteristic.

Thoresen’s analytical approach has been discussed in depth in other publications. [18]

The graph also gives a good survey of the melodic and harmonic progressions without pretending to present a Schenkerian graph.

Common elements

As already seen in Fig. 2, both themes share the descending motion y. In addition, if we consider the statement of theme B in A flat (bar 146), the pitches correspond to those of motif x. These are shown at the far right in Fig. 2. In the original key, the strand B2 combines both x and y in the original pitches (bar 65). The second bar of A1 also contains the rhythmic seed for B1, the iambic swaying. As for the episode, the variant of A at bar 116 uses the pitches of x integrated in the passagework as well as the sixth that serves as appoggiatura. Enough to call it a variant of the first theme [19]. As for the variant of the B-theme, this is clarified in the graph where its parentage from B2 should be obvious.

Shape of first theme: developing variation

I have already mentioned the fact that development is omnipresent in the work rather than confined to one particular passage, and certainly not to the place where it would be expected. The first theme is an example of perpetual development. If we stick to the division in three stanzas that I propose in Fig. 5, the first one, that might be called the theme proper (A1), consists of four two-bar phrases, of which the first and third, identical but appearing in different voices, might be called questions, and the two remaining ones answers. The fourth phrase resolves on the tonic after a dominant pedal point that has been moved one octave down at bar 5, creating suspense through the four phrases and a strong sense of closure at the resolve. Fig. 9 shows a detail of the overall motivic survey, concerning the first theme.

The aural graph (Fig. 7) shows a flat line through all of this, which will indeed be the case when the whole stanza is played as one line. In some performances, however, one will hear it split up into four separate phrases, which in my eyes is contrary to the sustained dominant pedal.

The next strands are both repeated 4-bar phrases, where the first pair (A2) both start with two accented double octaves; the second probably less strong than the first, letting the phrase drop while they use a combination of motif x and the chromatic auxiliary motif b. They are rendered with a downward slope in the aural graph. A3 is rather similar when it comes to dynamic shape although less accentuated at the start. Motivically, it uses the characteristic descent from F to C of the modified x’, intercepted by b and continued with y, so that these strands together may be called a developing variation; a reordering of the elements of A1. Harmonically, it also borrows from motif x by using the variant F-Eb-Ab (see Fig. 3), which I qualify as an inverted retrograde and which will return at several instances through the piece.

Rhythmically, these strands gradually introduce the sicilienne rhythm that will play an important role later (Fig. 10).

Note the subtlety with which the note-values of this rhythm are treated: ending on a quaver in bar 13, the other times on a crotchet (bar 14), on a rest (bar 15, RH), or tied over (Bar 15/16, RH). The pedal also plays an important role, and should be respected. This is where the dancing element is born which is going to dominate great parts of the work. Note also the ornamented version of motif x in bars 14/15, the shape of which is nevertheless unmistakeably C-F-Eb.

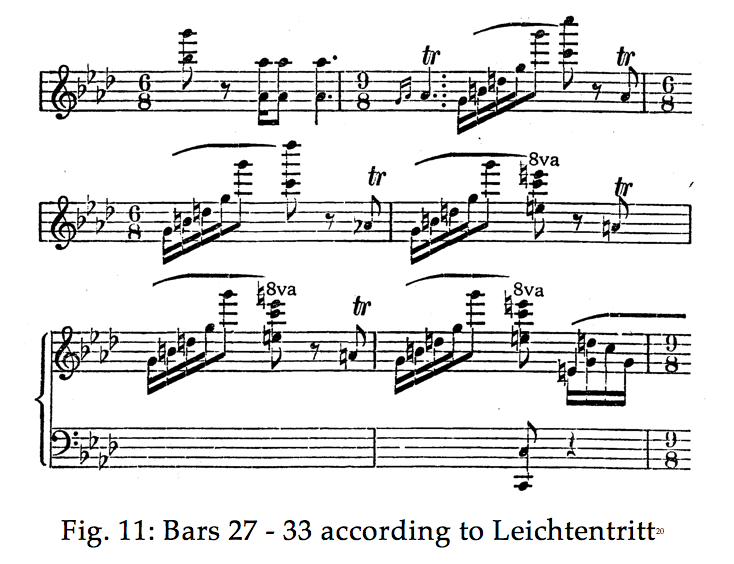

Then, at bar 25, there follows a development that will bring us to C Major, shown schematically in the last system of Fig. 9. It starts with the upbeat of bar 25 as a sequence where the G flat is the surprising element. There is a crescendo mark here, which means it should still be piano. The trills prolong the accent on this double octave into the next bar, and the same is repeated two bars later on the A flat. H. Leichtentritt proposes to move the barline at this point:

The top D on the second line must be a misprint. This is another example of the late 19th- early 20th century aesthetics, avoiding downbeats. In my opinion, the arrivals on C and E natural are structurally important, and should therefore stay downbeats. Through a liquidation process in bars 33-4, they lead to the F-E on the first beat of bar 35, which, with the preceding C, form a major version of motif x, anticipated in the left hand (see Fig. 9, last system). The aural graph shows a full luminosity here.

A short chromatic link leads us back to the repetition of A1 in bar 37. This reiteration is extended with a 4-bar sequential development of the third phrase (the second 1) that occurs in the bass and is then repeated in a higher register, bringing the final phrase (3) to the octave statement in the bass:

The concluding treble chord on top of the deep octave, characterised by Cortot ‘as a moonray on an idyll’ [21] gives a strong feeling of closure to the whole section of theme A, which, after an excursion to C major, calmly returns to Ab via the dominant. The bars of development shown in Fig. 12 are necessary to balance out the tension and to restore the calm in a masterly disposition of registers.

Second theme ambiguity C maj/F maj/min

In a way, this excursion to C major prepares the listener for what is to come. A iambic rhythm repeating a broken octave C is all that binds the two themes together, and theme B starts with a dominant 13th chord on C, reaches F major momentarily in the second bar and returns to C via its dominant in the last two bars of the period which is then repeated. An extra bar (62) is needed to stabilise the C major, before a new dominant seventh, reinforced by the 2nd degree, finally takes it into F minor. The parallel place at bar 255 is shown in Fig. 6.

Most analysts place this first stanza of theme B in F minor/major. Thoresen’s graph also underpins this. In the light of the above, I have difficulty in seeing this part of the theme as other than in C major, albeit unstable. The first half of the period indeed tends towards F major but then turns back, and the modulation to F minor takes place only in bars 63-64. I have two other reasons for this reading: In this same piece, the return of theme B1 in bar 146 doesn’t make sense when placed in D flat (C#) minor, since it clearly prolongs the stable A flat major in the middle section. Also, we have several other examples of Chopin playing with the ambiguity of a dominant-tonic relationship. A good one is to be found in the first theme of the Fourth Ballade. It starts off in F minor but ends in B flat minor. No one, however, has yet claimed this theme to be in B flat, and Chopin very discreetly puts it back in F before starting the second part at bar 23, although after the theme, he goes off to G flat in bar 38. In this piece, the instability does result in an F minor in bar 65, whereas the parallel place goes to C# minor.

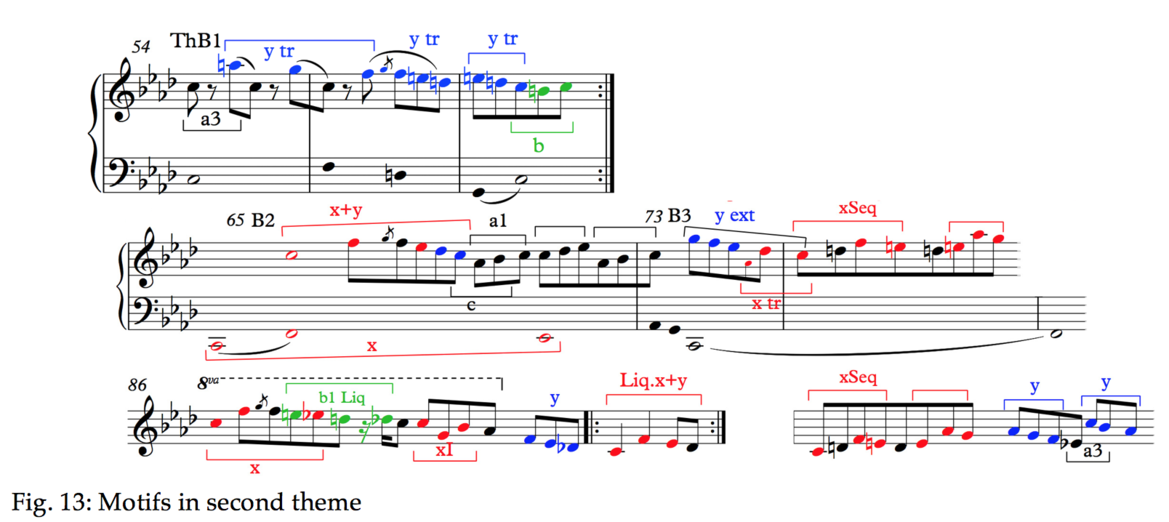

The rest of theme B will be more or less anchored in F minor, deviating momentarily to its third degree A flat, for which the bass makes use of the same formula that I referred to in bars 19-20 and that is part of the tonal sequence of Fig. 3. All this is shown in Fig. 13, another detail of the motivic survey. It also clearly shows the relation between B1 and B2 and the use of motif x, here in F minor with the same pitches as in the beginning.

What I call B3 here is a kind of development, extending the descent of B2 to start at G. Then the sequence of a formula based on x, on a dominant pedal point, intensifies the atmosphere and brings us to a reiteration of B2 in ff, the first one in the piece. This climax sets forth with a chromatisized descent in bar 86 that marks the beginning of another developmental passage starting in D flat. That will eventually bring back the pedal point sequence at bar 95 and the transition discussed above and shown in Fig. 4b. The aural graph shows the climax as a thick line, followed by one downward and three upward slopes, the last one leading into C major, again with maximum luminosity.

The last part of theme B will be a repetition of the first stanza emerging from the C major that is reached in bar 103. It stays, unresolved, on the C major. To summarise, we get the following scheme for theme B:

Is the theme then in C major or in F minor? I would say both.

Episode: elegance and passion

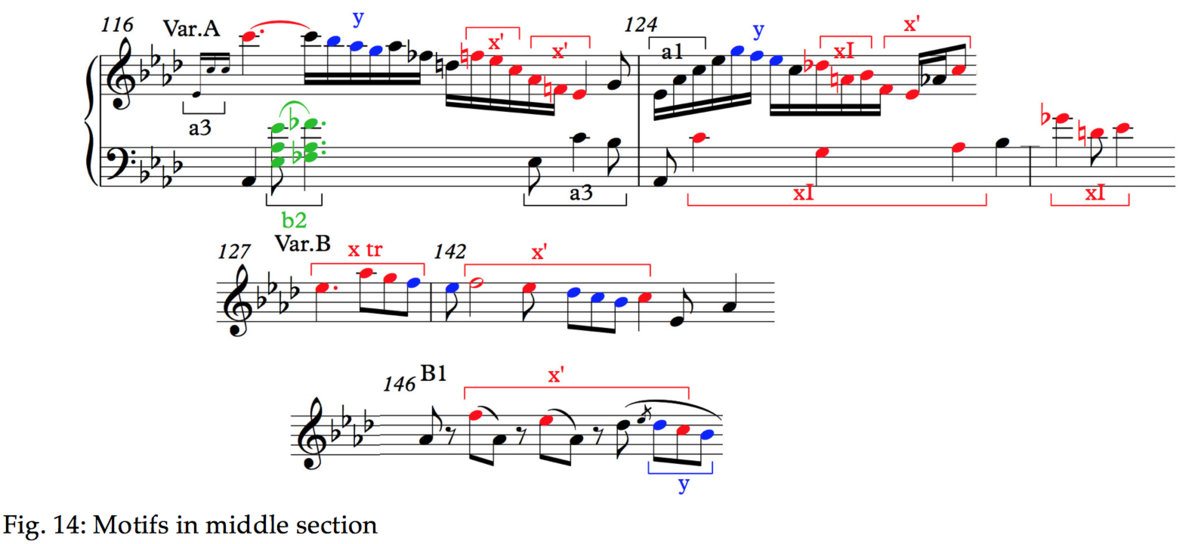

I have already discussed the role of this middle episode that suddenly emerges after the apparent appeasement on C major that concluded theme B. An expectation of a move to F minor having been created the first time heard, we are instead abducted to the main key. The music seems to take a new turning, but is still based on the material of the first theme, as I pointed out before. In Fig. 14 the reliance on the motif x in all the parts of this middle section is put into evidence.

The motif is used in various forms, permutated (x’), inverted (xI) or transposed (x tr). The first part of the episode is elegant, pianistically brilliant, with a typical waltz theme at bar 124, where the iambic rhythm is brought to the downbeat and the left hand offers motivic counterpoints. A counterpart of this passage is found in the first Ballade at bar 138. The second part is clearly derived from theme B and brings in a more passionate character, which is interrupted by the iambic broken octaves that announce the return of B1.

Darkness

As already discussed, the golden section falls in the middle of this return at bar 150, but the change comes in bars 155-56, leading into the C# minor section. A closer look at the figures accompanying the recapitulation of theme B2 reveals their dependence on the same motif x.

From bar 165 there is a prolonged upper pedal point on G sharp going on until bar 178, while B3 is heard in the left hand, that is providing bass, harmony and melody. B2 is then incorporated into this right hand pedal point at bar 173:

This is extremely effective piano writing, and the second ff in the piece, providing an impressive climax in the darkness. The first ff was at exactly the same point in the exposition, but with a quite different effect. Here, the turmoil of the semiquavers takes us into frantic desperation. In the left hand of bar 176 Ekier chooses a variant that I don’t adopt: the ossia is simpler.

After this, there follows a most energetic sequence going from C sharp in bar 179 in diatonic downward steps to B a ninth below. This formidable sequence, which comes at the place of the second B3, is shown in shortened form in Fig. 15, labelled ‘liquidation of the inverted motif x’. In Fig. 7, the bass progression is shown entirely. The B in bar 183 turns out to be a dominant since it becomes a long ornated pedal point supporting B1 then A1, both tending strongly towards E. The E had already been hinted at in bar 177 (see Fig. 16).

But here, the B is left unresolved and will find its resolution only in bar 226, as discussed before (see Fig. 3). Instead, the development of the strands of both themes goes on, transposed to C, D and finally to E flat, all felt as dominants. All this happens in a subdued, mysterious sotto voce. On B and C, the strands of each theme last 4 bars. The fragment of A1 is deprived of its x motif, since the top note doesn’t descend to the dominant until a bar later. On D, the sequence is shortened to twice 2 bars, and the first phrase of A1 is heard entirely, which enables us to recognise motif x again. This is repeated on E flat, the arrival point of this process, and prolonged by another 4 bars progressing chromatically into the recapitulation of theme A in bar 213.

Triumph after darkness?

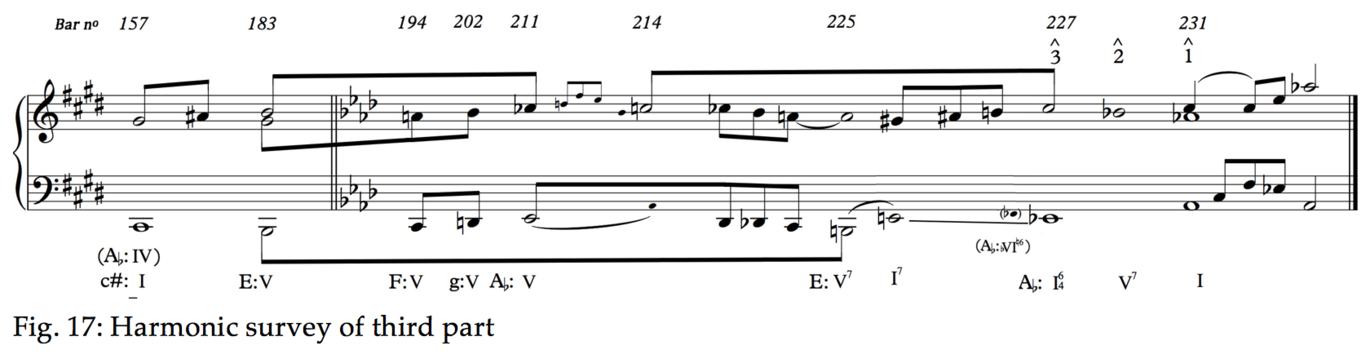

In the aural graph this progression is clearly visible. The luminosity changes from minimum to maximum, and the first theme is shed in this blinding light, whether or not it should be considered a triumph, see the above discussion (link) on this issue. As in its first appearance, the theme starts on the dominant but reaches the tonic already in the second bar, coinciding with motif x that now may shine fully. Whether the structural cadence is here or in bar 231, is another question that I already touched upon. To my feeling, the arrival on the 6/4 chord in bar 227 and the ensuing stretto and chromatic progression constitute the real cadence.

This can be visualised as follows:

This harmonic survey stretches from the C# minor at bar 157, enharmonically the subdominant of Ab, to the end of the piece. The structural cadence here comes after a cadence in E major resulting from the prolongation of the B from bar 183, enharmonically the lowered sixth degree resolving on the dominant. Placing the structural cadence on bar 214 would give the recapitulation of the first theme a psychologically different meaning, more like a triumphant arrival, whereas my view tends more towards a conception like Cortot’s, cited above, ‘intoxicated by its own suffering’. This would imply a slightly less massive ff at bar 214 (the ff is really in the previous bar), a reading supported by Chopin’s marking three bars later; a crescendo in the right hand (emphasising the arrival on C) together with a diminuendo in the left:

Note that my choice wouldn’t be based on literary references, as apparently is the case with Cortot’s, but on purely musical reasons. The variant in bar 216 is interesting, but I prefer the one given here as an ossia, which permits the accentuation of the C in the left hand, starting the subsequent diminuendo.

Frantic coda

What then follows, is a frantic restatement of the episode leading to a liquidation of its appoggiatura figure combined with the trill from bar 26, and a passage going from top to bottom of the keyboard, based entirely on motif x. The top F, the highest note of the piece, has been heard three times previously: first in bar 35 at the moment of great luminosity of C major; then in bar 131 topping the glittering passagework of the episode, and in bar 214 (repeated four bars later), where the theme is restated. The motif x follows us until the end of the piece: The bass in bars 239-40 states it a last time, providing an overwhelming conclusion:

The awareness of these relations gives a strong sense of unity to the piece, a sense of unavoidable logic, and at the same time one of unstoppable momentum. Confer with Fig. 15 and Fig. 17 above for the motivic and harmonic functions. In Fig. 7, the backwards arrow in the end could also point forward, but this will depend on the way it is performed.

Interpretative choices

Clarity vs. expression?

I have mentioned quite a few of the interpretative choices in the Third Ballade, and I am convinced that awareness of structural facts strongly influence these. A general choice would be that of tempo: it might vary somewhat between the sections, but must, in my view, keep the same basic pulse throughout, contrary to many of the historical interpretations. This may be a question of performance traditions, but I think it is more a question of individual choice. Horowitz does keep a unified tempo throughout, whereas Rachmaninov’s and Cortot’s performances have enormous deviations. True enough, Horowitz may belong to a different generation from the two others. But there are many “modern” pianists who indulge as well in exaggerated ritardandi or big tempo changes, for example in the passages with semi-quavers, such as bar 116 (episode) and bar 157 (C# minor). To take the episode in a more fluent tempo, and above all to observe enough freedom to value the importance of the ornaments, is acceptable, even desirable. But to play the C sharp minor passage almost twice as fast as the preceding one, is in my opinion a violation of the structure: this is merely a continuation of the second theme, and the change in colour is made clear by the texture and not by a new tempo. Moreover, the shape of the left hand follows the intervallic patterns of the main motifs (see Fig. 15) and needs a flexible legato in order to come out, not a mechanical prestissimo. Horowitz and Arrau respect this; many others don’t.

Clarity is not identical to mechanics: it should allow for expression, and the expression should not conceal the structure. This is, in my opinion, one of the foremost choices to make when performing Chopin. Indeed, the expression gains by clear intentions that underline the structure. A good example of this is the crescendo in bar 102-3. I haven’t heard a single performance that makes this crescendo (except my own, at 3’30). Is it because they haven’t consulted the right editions, or is it rather a leftover of outdated aesthetics? True, a diminuendo can sometimes have the effect of a crescendo, and Chopin did note a diminuendo and a crescendo simultaneously at several places in the Fourth Ballade [22]. In this case, however, a diminuendo in my opinion sounds mannered and blurs the harmonic progression.

Coherence first theme

A similar mannerism that has been part of a tradition is to make a subito piano in the second bar, after a crescendo to its first beat. This may sound charming and give this phrase an amiable, elegant character, and it does respect Chopin’s phrasing (see ex. 14a). But to my sense it also breaks the coherence of the theme, which resides on the prolonged dominant pedal point framing the four phrases that go from one voice to another. Both Cortot and Rachmaninov play the theme more or less like this. They both deliberately split the theme into four separate phrases, starting each one with a new impulse and dying away at the end. See Thoresen LINK for a detailed discussion of Rachmaninov’s performance.

Pedalling

There is another reason for not playing the F-Eb in the second bar too sweetly: it is a prefiguration of the iambic rhythm that dominates the second theme. The tempo should be similar enough to make it recognisable. Very few pianists whether ‘modern’ or ‘historic’, respect Chopin’s pedal markings in the second theme. They are not easy to realise but, when done well, they contribute to the innocent swaying of this first stanza:

The first bass of each bar is taken in the pedal, while it is lifted on the second one. This creates a gap that might scare some pianists; it is certainly more comfortable to envelop everything in the pedal, especially in the second and fourth bar, where you have to obtain a legato without using the pedal. Is it this challenge that prevents otherwise great performers to massively neglect such important indications by the composer? I doubt it. Again, it seems to be a question of aesthetics and tradition.

Darkness or brightness?

A vital choice to make is the one I have touched upon several times in the above. Is the Ballade basically a piece full of light and optimism, or does it end, like Cortot suggests, in tragedy? Many pianists play the development passage from bar 183 forte all the way, as if it were a joyous horse-ride rather than a mysteriously threatening pursuit. I think, in any case, that the return of the first theme at bar 213, and especially the arrival on the C of motif x, represents the end of a struggle, which is then confirmed by the cadence in bar 227-31. However, the introduction of chromatic harmony from bar 221 leading to the V-I in E major in bar 226, brings back the anxiousness of the previous development, and the coda, based on the episode, far from settles in triumphant solidity. The anxiety goes on until the end, bringing the piece to a relentless ending on our motif x, possibly pointing to another, unknown existence. This existential quest might be the real meaning of the Third Ballade.

References:

[1] Alan Walker: Chopin and Musical Structure, in Frédéric Chopin, Profiles of the Man and the Musician. Barrie and Rodcliff, London 1966, p. 227 [back]

[2] Ibid. p. 256 [back]

[3] Ibid., p.236 ff. [back]

[4] Jim Samson: Chopin: The four Ballades. Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 7 [back]

[5] Cited in G.C. Ashton Jonson: A handbook to Chopin’s works. William Reeves, London, p. 210 [back]

[6] Shown clearly in Heinrich Schenker’s graph, see Samson 1992, p. 48 [back]

[7] Cited in various sources, f.ex. Ashton Jonson, p. 210. Jim Samson pulls the existence of an earlier version in doubt, see Samson 1992, p. 53 [back]

[8] A term used by Schönberg. See also Does thinking enhance performance on this exposition. [back]

[9] Jim Samson refers to this: ”.. [forms] that meant a synthesis of the formal methods of popular concert music.. and the sonata-based designs and organic tonal structures of the Austro-German tradition. The First Scherzo and the First Ballade were the earliest fruits of that synthesis.” Samson 1992, p. 3. [back]

[10] James Huneker: Chopin: The Man and His Music, New York 1900. Dover edition 1966, p. 159 [back]

[11] ..un hymne de désespoir, enivré de sa propre souffrance.. Apothéose, certes - mais de la souffrance et du désir inapaisé. Alfred Cortot: Edition de travail, footnotes to bar 183 and 213. [back]

[12] Arthur Hedley: Chopin: The Man, in Frédéric Chopin, Profiles of the Man and the Musician, p. 4. [back]

[13] Samson 1992, p. 26 ff. [back]

[14] Ibid, p. 31 [back]

[15] H. Leichtentritt shows how it is used as a rhythmical/melodic motif in the following bars. Leichtentritt: Analyse von Chopins Klavierwerken II. Max Hesses Verlag, Berlin 1922, p. 21. Alan Walker, however, joins it with the fourth as I do, although he calls it y. Walker 1966, p. 236 [back]

[16] This alternative is brought forward by Jim Samson, referring to Anatoly Leikin and then dismissing it. Samson 1992, p. 61/62 [back]

[17] Il sera bon de laisser pressentir cette modification de caractère dès les premières mesures que l’on jouera dans un sentiment de trouble et d’inquiétude, précurseur du dramatique développement qui, peu après, l’emportera dans sa fièvre. Cortot, footnote to bar 144. [back]

[18] Lasse Thoresen: Emergent Musical Forms. Aural Explorations. Studies in Music from the University of Western Ontario, Volume 24. London, Ontario 2015. Web-page: www.lassethoresen.com. Thoresen, L. 1987. An Auditive Analysis of Schubert’s Piano Sonata Op. 42. Semiotica, 66(1–3): 211–37. [back]

[19] Alan Walker supports this viewpoint as well. Walker 1966, p. 238. [back]

[20] Leichtentritt 1920, p. 22 [back]

[21] comme un rayon de lune sur une idylle.. Cortot, footnote to bar 35. [back]

[22] At bar 11 and similar places. [back]

[back]

[back]

Fig 2 anchor - [back]

Fig 5 anchor - [back]

Fig 7 anchor - [back]