Figure 11: “Free way!” This advertisement highlights the value of horns with a penetrating sound. It is one of the many publications that offer horns with various intensities and tones. This shows a contradiction with the municipal norms establishing the sonic characteristics a horn must have, and its use as final resort (image from a “Bosch” advertisement 1936).

The public agenda thus focuses on the incorrect uses of this acoustic warning device. In 1939, an ordinance stipulates that between 1am and 7am, honking must be replaced by flashing headlights (anon. 1939b). Even though this provokes resistance from the A.C.A., which suggests restraining the use of horns to only when strictly necessary, the ordinance is effectively implemented and evokes a change of habits which nowadays goes largely unnoticed. In 1942, with ordinance 20820, the time frame is extended up to 10pm (anon. 1942). In 1943 a regulation which forbids the use of horns downtown and on avenues is announced (anon. 1943a). This regulation was doubtlessly aimed to make street activities less dominated by the arbitrary use of horns as well as to encourage speed reduction. However, the A.C.A. objects to Traffic Management, saying that, before banning horns, an education program for pedestrians must be implemented to prevent accidents (anon. 1943b). In the end, the regulation had no real effect (anon. 1944).

In this section, we have presented a series of legal efforts by the state in its fight against annoying noises. As we have shown, annoyance arises from the perceived uselessness of these sounds. Various norms and their implementation through police regulation aimed to remove specific practices rooted in the street habitus (Wright, Moreira and Soich 2007). In other words, socially learnt patterns are ascribed to a general lack of culture. As a result, official campaigns emerged as an encouragement to subvert the imaginary of what is possible – within the confluence of the sonic, the technological, and street life – in the search for bringing together a new moral code and a new model of the ideal citizen. Nonetheless, noise continued to be a cultural problem, and the legal system remained abstract, without practical application. Consequently, even though there are still pretensions to regulate each and every type of sound that affects the individual and social body, street noise has constituted itself increasingly as the main issue of conflict in civic coexistence.

Please, Sir, the Horn!

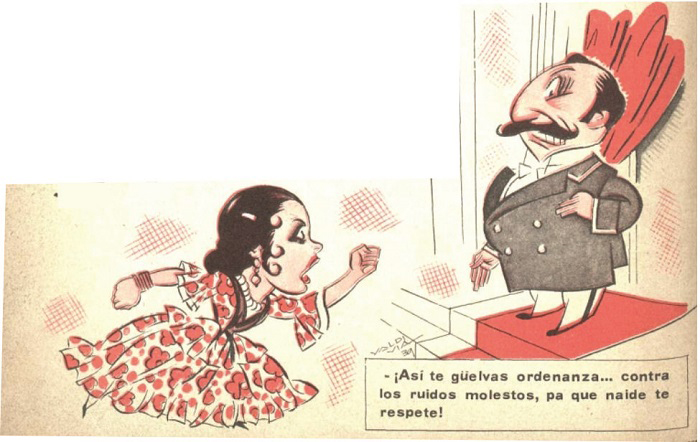

In 1939, Caras y Caretas published a cartoon that synthesizes the relationship between Buenos Aires’ citizens and state norms against noise. It is a kind of gypsy curse that transforms the addressee into an ordinance against annoying noises. With this curse, no one will respect him.

Figure 9: A Gypsy woman curses (colloquially) a man in a suit so that he turns into an ordinance against annoying noises who will no longer be respected. This cartoon addresses the relationship between citizens and ordinances against noise (image by Rosso 1939).

Through the years, different rules were released that aimed to regulate annoying noises in the public sphere. As we have demonstrated throughout this article, the parameter of annoyance, eminently subjective, is established according to social boundaries of tolerance. There are sounds that will not likely be listened to with pleasure, but they are assumed to be part of the typical sonic ambiance of a city, not corresponding to a specific activity or an identifiable subject; they are impersonal noises that are not attentively listened to, while at the same time forming a part of the testimonial background of modern sonority. The state will use legal norms and instruments to banish those practices that produce, directly or indirectly, sounds that threaten its civic ideal. These sounds, deemed intolerable, are associated with identifiable citizens whose habits, thus, must be modified through police sanctions and monetary punishments. A system of codes, ordinances, and regulations is built that encourages the removal of certain sounds from the public sphere, primarily traffic sounds. In our ethnographic analysis of this system, we account for the state’s attempts, not only to restrict urban sonority to what is deemed to be within a civilized framework, but also to influence the daily behavior of its citizens. What is interesting is to understand how implicit rules, socially learnt and interiorized, are configured in a practice which regulates the ways in which people behave outside, on the streets:

These rules are the grammar that allows for intelligible communication among actors so that traffic life can occur. Furthermore, these rules appear to be the performative actualization of traffic norms, which leads in practice to the generation of a parallel system of norms, native norms, by means of which we know what to do in each situation that leads us to process our traffic knowledge. (Wright, Moreira y Soich 2007: 10, emphasis in original)

The native norms generate a distance between the moral norms of a society – or, rather, the imaginary of what is possible and how things are done – and the state commands imposed through laws, reinforced by the presence of the police. However, we see here how these rules are not simply obeyed by passive individuals; rather, a history of relations is developed, expressed in a “semiotic rebelry” (Wright and Grimaldo 2018: 155), a contextual interpretation of the signs coming from the state and a constant negotiation regarding their possible meanings. There are some critical factors to consider here. On the one hand, an underlying social mistrust of state orders and, consequently, the expectation that regulations will not be obeyed. On the other hand, a general reluctance to devise an efficient way to control the evanescent and ubiquitous qualities of sonic phenomena. Clearly, the first attitudes facing the ordinance against noise promoted during Arturo Gramajo’s administration (1915-1916) are categorically negative.

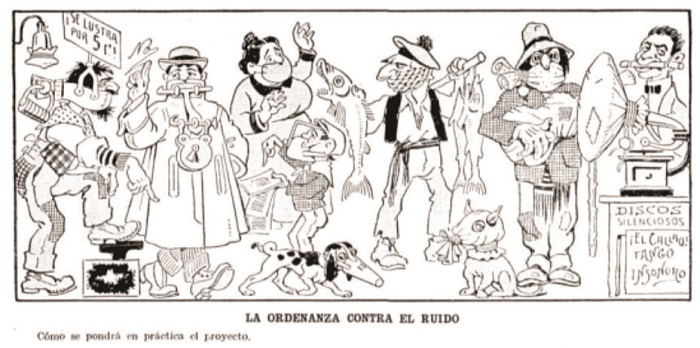

Figure 10: “How the project will be implemented.” This image makes fun of the attempt to control noise in Buenos Aires and represents the first negative reactions to the ordinances (image in Polimani 1915).

The image represents the arbitrariness as to which noises are or can be annoying. If there is a set of noises that can be equated with modernity, what to do with all those noises associated to the uncultured? It was noted that in European cities, norms had been efficiently implemented to regulate the sonority of the social body, while in Buenos Aires

we, despite existing projects and decrees, continue to live in a sonic hell. Loudspeakers, tram bells, car horns and sellers’ yelling electrify not only the day but also the night. (Castillo 1934)

It is a public urban scene in which vehicles and offers for objects, services, and cultural activities are abundant. Voice amplifiers and instruments calling people’s attention – all taking advantage of the new volume levels of audio reproduction systems – threaten the modern imaginary of a civilized city. Therefore, the state takes on the role of regulating the sonic order, establishing a fine line between what is allowed and what is not, a system of legal norms aimed at imposing a moral code. These events mark how, little by little, Buenos Aires comes to be thought of as a noisy and messy city, far from the modern imaginary. In 1934, ordinance 5388 is approved, which attempts to regulate the emission of annoying sounds, meaning those useless and unnecessary noises in the streets. However, this ordinance rapidly falls into disuse, remaining as a useful resource without any actuated effects. Six years after its approval, the norm reappears, mainly in regards to street sounds (anon. 1940). The ordinance established, among others, the prohibition of free flow exhausts and the legal conditions for horns: that they be of low volume and only produce one tone.

the 1930s, free flow exhausts lose their status as the most annoying noise, horns taking their place. Complaints focus on their unmeasured and unnecessary use, already penalized by ordinances and traffic laws. Nevertheless, certain horn uses, those which might reinforce traffic security, are tolerated. In 1923 the Automóvil Club Argentino publishes a pamphlet distributed from the police headquarters that notes the obligation to sound your horn when approaching a turn in the road (anon. 1923). When reaching a corner, the driver must slow down, press the horn once, briefly, and then progress. Horn usage had, in this description, two main functions: as a final warning of imminent danger, and as a warning before a crossroad. However, real usage far exceeded these functions, thus neutralizing the initial ones.

Instinctively, the driver presses the button placed on the upper part of the steering wheel, not caring about the effect the loud sound has on the one who hears it. And the listener has become indifferent to this noise. The sound has become meaningless. (Strong 1927, emphasis added)

Instead of functioning as a last resort, the horn dominates the urban soundscape with multiple possible meanings, including a way for drivers stuck in traffic to vent their emotions. Moreover, a relation between its sound and driving speed is established. Drivers, rather than slowing down in corners and sounding horns, invert the situation: already halfway through the intersection, they start sounding the horn and speeding up (Driver 1940; 1941). As a result, the horn gradually is perceived as the most annoying traffic noise. Its unrestrained use confuses people already confronted with multiple stimuli produced on the streets. Furthermore, unlike free flow exhaust systems, horns are obligatory for all vehicles. As a consumer item, horn advertisements are plentiful in the Automovilismo magazine. However, the qualities we have noted in these ads – horn intensity and multiple tones – reveal a contradiction with the legal attempts to regulate its use. The main punishments are then gradually directed towards the use of horns, following article 10 of the revitalized ordinance 5388.