Noise as an Urban Problem

In the historical documents of our research the association between noise and progress is rapidly abandoned during Buenos Aires’ progressive transformation into a metropolis. Soon afterwards, this new sonic space starts being perceived as a root of problems for civic coexistence and inhabitants’ health. In a conference on Paris and Buenos Aires held in 1929, Le Corbusier asserts that noise is a symptom of urbanism, as the narrowness of streets and the vehicle flood produce a reverberation that turns intolerable for him in the “inhumane” city of streets “without hope” (Le Corbusier 1999: 224). The material conditions of downtown Buenos Aires work as acoustic amplifiers that no longer express progress in a modern imaginary. On the contrary, they threaten such progress, as the positive view of urban circulation and vitalism begins succumbing to the negative impact of noise on the social body.

Once the hum of urban movement has been established, some sonic practices begin to be signaled as problematic elements that should disappear, mainly those sounds that, because of their power and sudden appearance, stand out of the background to which the urban subject has gradually adapted. They are signals (Schafer 2004) that, like peaks in an oscillogram, impose themselves upon people’s attention. Certain sounds start being condemned and defined as noise by people writing in magazines. Simultaneously, the same term is used in ordinances and regulations[12] aimed at easing civic coexistence. This is the case for the use of free flow exhausts in motorcycles and cars. A recurring question in Automovilismo is whether their installation brings any benefit for the machine’s functioning, both in terms of efficiency and mechanics. Some state that the free flow exhaust placed near the engine allows for a total release of burnt gases, whereas with another method some residues stay in the system due to accumulation in the shock absorber (Delfino 1927). Another advantage mentioned is that paying attention to the sounds of a free flow exhaust in a four-cylindered engine allows for easy auditory diagnosis for correct functioning (anon. 1920). However, the general opinion is that free flow exhaust systems are being implemented by citizens without consideration for their environment, damaging the inner ears of inhabitants and intruding in their private lives:

Let citizens be annoyed just so that he [the man who uses a free flow exhaust] can have fun! He achieves his task in life: zooming around but going nowhere and spreading useless noises, as useless as the insipid ideas that germinate from the brain of an idle man. (Indarte 1928)

A remarkable aspect is that this debate actually takes place at a time when free flow exhaust systems had already been forbidden for many years by a number of ordinances. However, they keep being used, and that is why magazines’ authors highlight over and over the uselessness of the norms. The practices are continuously banned but without real consequences. This process reappears in the traffic issues regarding the misuse of horn and tram bells and in the persistent use of steel tires instead of rubber ones. These sounds do not belong within the sphere of what is necessary; therefore, they act against the modern city’s sonority. In 1933 Buenos Aires was host of the Congreso contra el ruido (Congress Against Noise) (Ronacín 1933), which adopted the Cartilla del silencio (Silence Cart):

In order to suppress useless noises, we must search – within the potential of good education – the virtue of making people understand that shouting, strident sounds, and intolerable noises, are attempts against the health of the child, the mother, the adult, the elderly, and the ills. (anon. 1933)

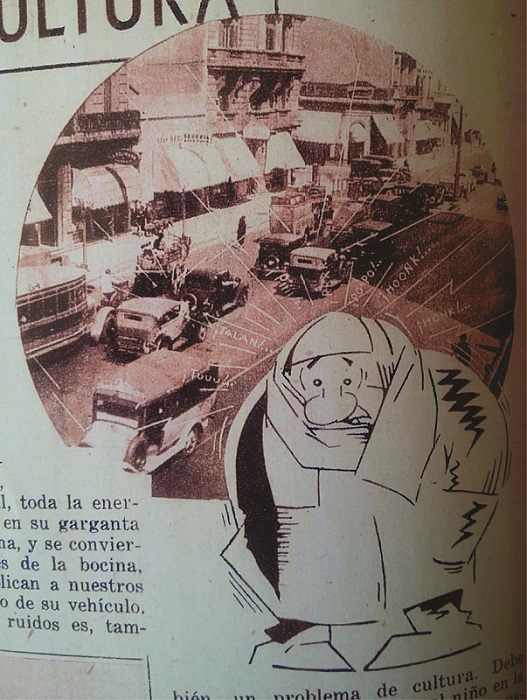

Useless noise, thus, was understood to affect people’s health as it bombards the nervous system, producing a state of stress, exhaustion, and sadness (Castillo 1934). One corollary was that noise began to be conceptualized as a cultural problem:

The inhabitant of a cultural center such as Buenos Aires, who brags about a good steering wheel, does not sound the horn: first, because he is a good driver; second, because he is a civilized individual for whom excessive noise is understood as a negative attribute of all culture. (anon. 1936)

Figure 5: Unexpected and sudden noises can trigger a medical condition known as neurasthenia, a state of stress, exhaustion, and sadness (anon. 1939a).

Thus, legal and moral rules develop over time with the aim of making people abandon the sonic practices that are considered excessive in an already saturated environment. However, the alteration of social habits is portrayed as an almost impossible task. The constant hustle and bustle becomes established as a negative aspect of the city, associated with certain people who have no awareness of the effects of their sonic practices. Speed and noise, symptoms of a growing city whose governing bodies lack the time or willpower to administrate them, are now considered as a source of social and individual unease. The modern imaginary that linked civilization to noise now turns to the demand to reduce it, aiming for a new ideal of nonintrusive noise. A city, by definition, will continue to be noisy, but it must be so only in the background, signaling urban movement.

In the private sphere, silence becomes an added value to consumer goods. In advertisements of typing machines, recording and reproduction devices, fans, car engines, et cetera, the absence or reduction of noise is mentioned as a quality. Alongside the growing tendency toward the acquisition of electrical appliances, houses, offices, and other workplaces aspire to reduce avoidable sounds to a minimum. These are spaces designated for rest and/or concentration, therefore requiring a certain “acoustic intimacy” (Dominguez Ruiz 2015: 2). As a result, bedrooms are located far from the street so as to avoid the intrusion of noises from public spaces.

Various sonic residues, both cultural and technological, must be removed from everyday life. European cities such as London become the role model for an efficient policy against annoying noises, but their methods prove to be unrepeatable in Buenos Aires due to the cultural habits of its inhabitants. Hence, noise becomes one of its critical polluting factors:

For many, noise meant progress, and in this way civilization was heard to keep improving. But, currently, noise has become one of the most serious problems, and authorities of the whole world are beginning to understand that noise is as damaging to health as germs, dust, and the smog of the big cities. (Podolsky 1939, emphasis added)

In these first decades of the 20th century, cities continue to be the spatial referents of noise. Nonetheless, the significance of noise has now radically changed within societal discourse. The civilization in which it was produced now recognizes it as an element to be fought against. Noise, air, and water pollution have become the focus of the latest urban hygiene policies, a sanitary model of the social body. These are all simultaneous processes. In the modern imaginary, new ways of controlling the practices not yet conforming to the new ideal of relative silence must be found.