3 - On choosing harmonization

There are many ways to harmonize a melody. Jazz musicians, when accompanying often have a melody with chord symbols written on the paper, which allows lots of freedom to pick certain rhythms, voicings, or alternate changes and pianists and guitarists usually know may ways to get from one chord to another.

This research does not focus on how voiceleading rules work for jazz harmony or which embellishing chords to use, like passing- leading, or alternating chords, for that has been extensively described in other books, like throughout Frans Elsen's Jazz Harmony at the piano books, that I highly recomend. What I would like to show in this research is that jazzcompositions often take unexpected turns, with interesting harmonic movements, and I would like show ways of finding these subtle colorfull chords when writing.

Turnarounds

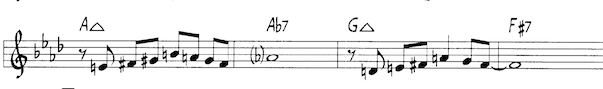

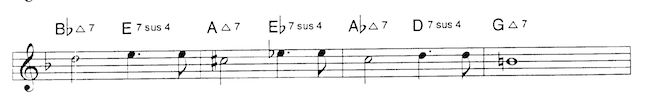

When the pianist and well known Dutch comedian Mike Boddé was doing his masters in jazz composition a few years ago here at the Royal Conservatory in Den Haag he got an assignment from his harmony teacher Eric Gieben to write down 60 different turnarounds.

Mike told me that was one of the things he really remembered as being useful. It actually turned out to be quite an eye opener for him. Here to the right you can see the paper with the variations he handed in. One could argue that these are not all really turnarounds, but they do - in his view - serve that purpose, and they convey quite diverse feelings, which is the whole point.

Really knowing a lot of possible ways to get from one place to another harmonically, makes a lot of sense. It’s probably like having a huge vocabulary so one can express oneself in exactly the right way. Think of the cliché of the 50 words for snow in eskimo languages.

Finding the most appropriate way to get the feeling you want for the music, means having different options, and knowing the effect certain harmonizations or chord movements will have. It’s is nice to develop a broad palette so to say, a vast field of possibilities to choose from, with every possibility having it’s own atmosphere, with it’s own associations.

In interesting jazz composition or improvisation there is often a subtle balance between what you expect or “felt coming” and what surprises you. Depending of course on what a composition is intended to arouse, you can either choose harmony to be either soothingly predictable or simple, to complex, dramatically dissonant and unexpected for example.

On the one hand, music that is too predictable all the time is often boring (like elevator music), but on the other hand music that is never what you expect, and constantly does something the listener can not relate to can put people off too. It’s in the balance between the expected and the unexpected, and all the nuances in-between, that can take the listener on an interesting journey. Like in good storytelling the listener is taken along, and hopefully encounters some surprising, uplifting or moving turns along the way.

In a composition class, my usual advice to students is if certain chord changes are intriguing to them, to find out exactly what the harmonic movement is. I urge them to play the chord changes in different keys, see if they can find other tunes in which the same chordal movement happens, find common tones between the chords, see how the scales that fit the changes relate. Also to find out what the essential tones are, and which notes in the chord are for coloring.

Examples

The following examples that I will now describe are a few typical progressons that have become commonplace, or cliché, and my point is that students should get to know them, recognize them, and will natually end up using more and more of them when writing their own music.

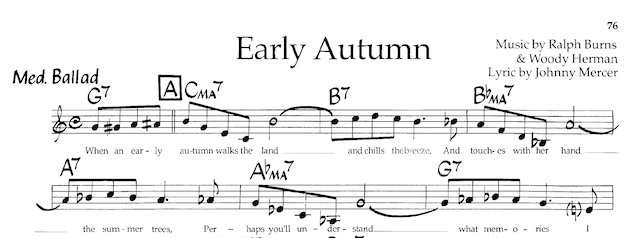

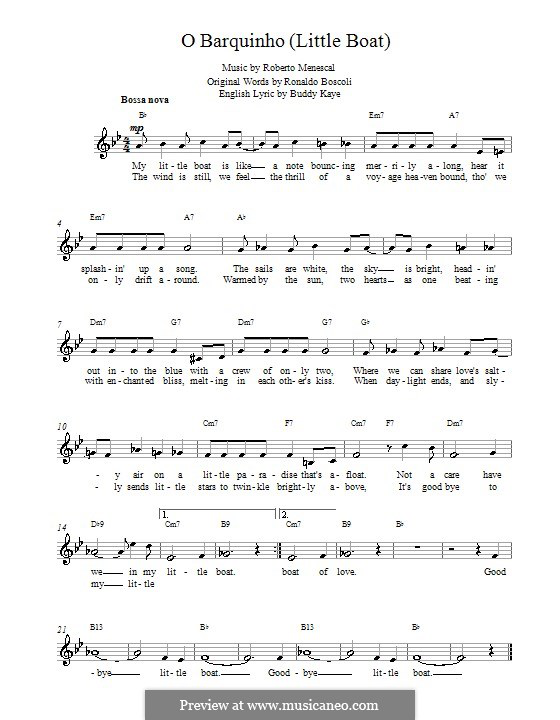

I often come across the fact that students are not aware that they might allready know a certain harmonic progression, but in a different context. Because it's in a different key, with a different melody they don't realise that the chordal motion is identical or very similar to many other tunes. It is very helpfull to compare songs in which the same chord progression lies under a totally different melody, or has a different function. For example take the first 4 bars of Early Autumn, going down in whole tone steps every two bars. It's very similar to the chord progression in "O Barquinho" (My Little Boat by Roberto Menescal), or similar to bars 5 through 8 of Benny Golson's Along came Betty, though one might not experience that as such. This chord motion happens in many other tunes, and by listening to them, and playing this progression in all 12 keys, it becomes one of the many sounds one becomes familiar with, and will eventually become one of the things one will have at hand when the situation calls for it. That's why it's a good idea to take a nice chord progression round the cycle of 4ths or sequence it in other ways through all keys, to really become familiar with it.

Another harmonic progression that is often used, major chords going down in half steps with secondary dominants (or II V) in between, is found in the bridge of "Daydream" by Billie Strayhorn, That same motion can be heard from the 9th bar of Sonny Rollins' "Airegin" or in the bridge or Kenny Wheelers "Everybody's song but my own" (at 1:49) More about this song in the next chapter. It's a chord sequence I advise students to experiment with.

I could name many other tunes in which this harmonic sequence occurs, but the point is that when you anayse the progression, and play around with it in all the keys, you will have it at your disposal when a situation comes when it might come in handy.

The effect of choosing certain harmonisations

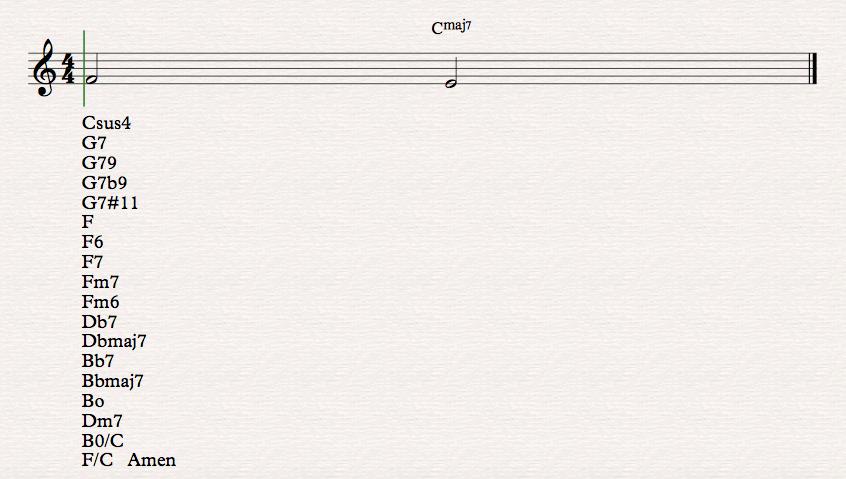

When harmonising a melody the degree of dissonance can determine the emotional inpact. For instance take a melody that resolves from a 4 to a 3 in the major scale. Many jazz compositions make use of this tension/release, like in "I will wait for you" (Michel Legrand) where the tension/release from the 4 to the 3 is used in allmost all uneven bars both on minor and on the major chords. This list of possible harmonic choices on the right is far from complete, the chords have different functions (plagal, tritone substitutes, parallel) and it does not even deal with inversions or voicings. The point I'm making is only that there is a lot to choose from, with varying degrees of dissonance. Some sound sweet, some blusey, some can make you feel you're in Spain... Try them out, compare them. The gratification of resolution depends on the harmonic path chosen. Sometimes you'll want the harmony to create a sense of forward motion, showing the way, and at other times you'll want it to drift along without implying the direction.

This example is leading to a tonic chord, but it's good to chart the many ways to reach all other kinds of chords. To start with the scale degrees, how can you get to a 2nd degree, 3rd, 4th etc. etc. And then the non scale degrees, the modal interchange chords, try ascending to chords or decsending, stepwise, chromatically, there are so many possibillities to get from one harmony to the next.

Excercises

As an excercise I let my students write down all the harmonic variations they can find for the first 4 bars of a blues, with examples from the repertoire, like for instance in Bluesette, Some other blues, Wave, or West coast blues. Then see if they can hustle them up, combine them in a differnt way and come up with something of their own. Some fit their melody, and some clash or feel awkward. What I often notice is that when I confront them with a clash or a awkward harmony many students often pretend it to be intentional, and they say they enjoy the effect. I find it important that students use harmony that they actually hear in their head, in stead of something that they rationally know should be correct.

Another example of a good excersise, similar to the "Daydream" chromatic sequence is taking the first four bars of Whisper not, and continuing the harmonic cycle through twelve keys.

Cm Cm7/Bb | AØ D7 | Gm Gm7/F | EØ A7 | Dm Dm7/C | BØ E7 | Am etc. etc.

One can embellish these harmonies in many ways as can be heard in this beautiful example of that sequence played by Clare Fischer.

"Move me" notes

A note that seems wrong at first, until it is moved to a more consonant note in the harmony, one that does make sense, Barry harris refers to these as "move me notes", notes that seem a mistake, and resolve a half or whole step to a logical chordnote. There are quite a few of them in this Clare Fisher recording.

In their paper "Fundamental Passacaglia: Harmonic Functions and the Modes of the Musical Tetractys" Karst de Jong and Thomas Noll wrote about this.

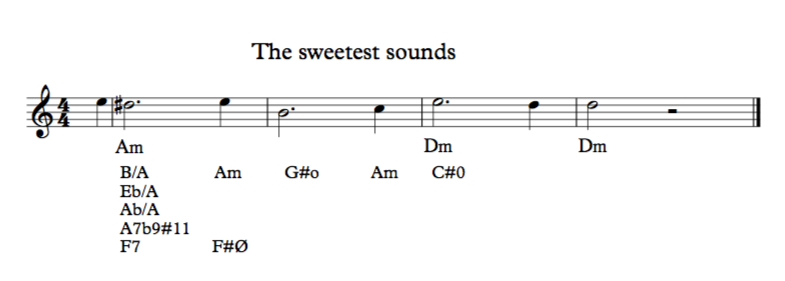

Another tune that starts out with a nice move me note is Richard Rodgers tune "The sweetest sounds"

The raised 4th, or flatted fith of the opening minor chord could be harmonized many ways, with widely varying degrees of dissonance as shown here on the right.

Harmonic cliché

Many harmonic turns have become commonplace or even cliché in certain style periods. The usage can evoke the feeling of the effect sorted by the chord movement. In terms of emotion for instance let's look at the harmonic deviation from a major key to a major chord up a major third, say from C via F#Ø B7 to E maj7 which happens in standards like "I love You", "The touch of your Lips", "I'm Old Fashioned" or like the bridge of "The song is You" when the section modulates to that key. In my experience the effect could be described as a light, pleasant feeling, as if the sun comes out from behind a cloud. It's allso interesting to compare these alternative progressions to reach that key, for instance Cmaj7 D Emaj7, or Cmaj7 F7 Emaj7.

Repetition, using common tones between chords

Another good exercise is to examine tunes in which a single pitch is repeated many times, with changing harmonies, like in the beginning of "One note samba", "Con Alma" or "Come rain or come shine". Just to see which chordnotes change, and which remain the same. It gives you a lot of information about harmony, voice leading and harmonic rhythm. It's often an eye opener for students that think a note is accompanied by a chord, where as it is often a whole string of chords behind one note. Common tones are often the notes that pivot chords use to go in another direction, though not necessarily.

It's good to know clichés that often show up in jazz tunes, and I will name a few common ones for when a note is repeated and one (or more) of the other inner voices change.

When the melody is the 3rd on a major chord, and the 5th is augmented like in the A section of Daydream that I mentioned before. Other tunes in which that exact thing happens are Richard Rodgers' "I'm a cock eyed optimist" , or "It Never entered my Mind"

Another cliché is to raise the 5th on a minor chord like in James Bond themes, or "Cry me a River". Often the raising of the 5th on a minor chord is used on weak bars, or weak beats of the bar. The effect if quite different when used on the strong beats of a bar (for example the 3rd bar of the bridge of "More than you know", or the 6th bar of the bridge of "The Gypsy") you hear a 3rd degree minor chord in which the melody is the raised 5th, that drops to the 5th, a typical "move me" note.

Main chords versus embellishing chords.

It's good to know the main chords of a tune, the ones that mark the harmonic structure, in contrast to the embellishing, approaching, passing or alternating chords that just as well could be left out without really changing the basic structure. These embellishing chords often harmonise the embellishing tones, usually a dissonant in the main chord, and mainly decorate the essence of the harmonic progression, but do not alter it.

Moving around with diatonic passing chords, like can be heard on the first 4 bars of "When Lights are low" creates movement, but the basic function is just a tonic chord for 4 bars.

The bluesy choices.

First of all we’ll determine what makes a certain harmony sound "bluesy". The blue notes in a scale being the flat 3, flat 5 and flat 7, one would expect the chords containing those to be bluesier too.

So instead of C maj 7 | Dm7 G7 | C you could replace the Dm7 by a D7b9 containing the Eb and the other blue note F#. Or by adding the flat thirteen and flat ten to the G7, so it also has two blue notes. Also in minor replacing a two chord (DØ in Cm) by a D7 or Ab7 gives a bluesy touch because of the F# (or Gb).

For instance the normal and common turnaround in Cm (Cm AØ | DØ G7) becomes bluesier by playing Cm A7b9 |D7b9 G7.

Or a turnaround in C major becomes bluesier by playing C Eb7 | Ab7 9 Db7 9 13.

When going to the IV chord the maj7 will sound sweeter, and the 7 chord bluesier.

When going to the flat VI chord the same applies. All thes movements and all of their voice leading have been thoroughly and exhaustively described by Frans Elsen is his harmony at the piano books. Here in all kinds of passing chords, approach chords, embellishing chords, alternating chords, leading chords and suspending chords are explained in depth.

Tritone substitution

I could include a whole chapter on tritone substitutions, a very very interesting harmonic (and melodic) subject in jazz, for which I have done considerable research that resulted in a special masterclass on the topic at at the Amsterdam conservatory that I did last year. The tritone sub often that replaces a V chord, a [V] chord or an augmented I chord, and can have quite a surpring effect. I wont go to deep into this topic here because so much has been written on this subject, for instance again in the books on harmony by Frans Elsen, that I recomend highly. It's a harmonic device that - if it doesn't clash with the melody which it often does - can be fantastic way to reharmonise a melody, or a dramatic way to make a outrageously dissonant melody sound like it is perfectly logical. If you look at G7, the dominant in the key of C, the two important notes that define the character of the chord are the third and the seventh, B and F. They are exactly the same notes that define the tritone sub Db7, but then F is the third, and B (or actually Cb) is the seventh. The pull towards resolution remains, the F descending to the third, the B ascending to the root, or to the seventh if the resolution is a 7 chord.

Leaving out "essential" notes

Herbie Hancock othen tells the story in interviews about working with Miles Davis, that Miles told him once to leave out the "butter notes" and that opened up a whole new world for him, playing voicings without the essential thirds or sevenths. So apart from which chords to choose, how to voice them, or which notes to leave out from them (or to double) makes for specific effects in the dramatic usage of chord voicings.

Pedals

An widely used technique is employing pedal points, or ostinatos in the bass with shifting harmonies on top. (in many styles of music) In jazz the fifth in the bass is most common (Moments Notice, This I dig of you), and also sometimes the tonic (On green dolphin street). David Berkman devoted a chapter on the subject, showing well known examples. I would like to add this nice example by Jobim "Chovendo na Roseira" (the pedal point starts at 00.49 seconds) with chromatically desending chords under a diatonic melody. Here is the sheet music

Describing in emotional terms

Music is often described in emotional terms, melody, rhythm, groove or the sound makes you feel things. Ways to get from one harmony to another can also be described in emotional terms, using words like gentle, harsh, friendly, dirty, smooth, sweet, bluesy or sunny. These ways to describe harmonic progressions can be very usefull, allthough these terms are of course very subjective. Even so I argue that it's good to not only know many ways to get from one place to another, but to be able to describe them and compare them.

Arriving at a certain place is hopefully a gratifying experience, and the journey to that place an interesting one if you feel or learn something on the way.