Atmospheres

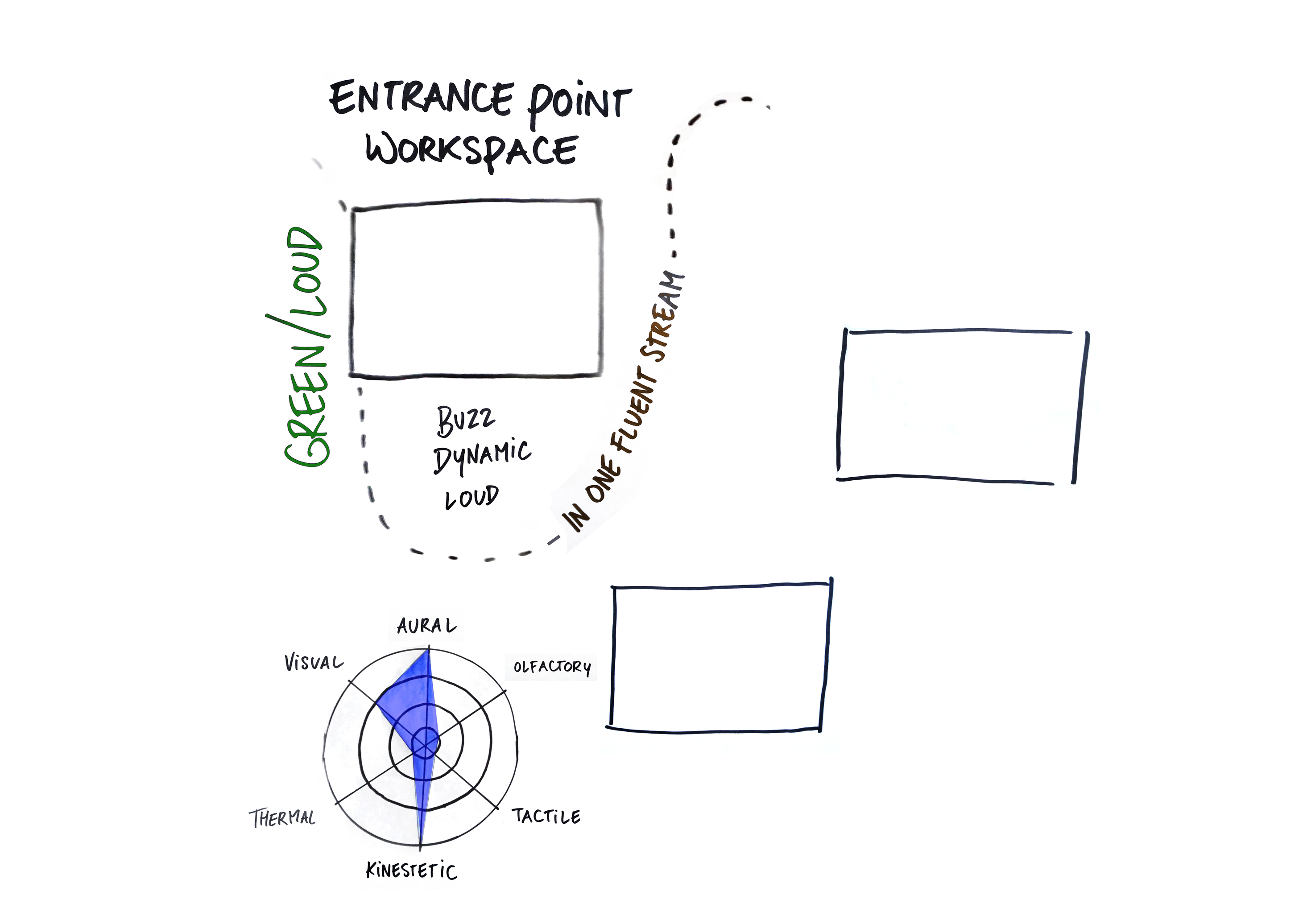

The concept that is at the heart of our exposition is atmosphere. This concept points towards the immediate felt perception of a particular space or environment. A room can feel too hot or cold, as much as it can appear intimidating or inspiring. Atmospheres emerge from neither inside nor outside, subject nor object, but radiate before and through environments – sometimes as pleasant, warm or wounding; other times as mundane and hardly noticeable, yet others as a temper or an attunement to a situation and its mood.

Crucially, atmospheres are always present and condition how things show up for us: they are ‘felt from inside, within, and not in analytical distance. They are, moreover, felt differently by different people’ (Pink, Mackley and Morosanu, 2015, p.353). We not only live through atmospheres but make them as well (ibid., p.354). What is at stake, here, is the dynamic intersection between experienced environmental surroundings and the beings inhabiting these spaces; together, they constantly form and are affected by atmospheres. Put differently, ‘atmospheres are always located in-between experiences and environments’ (Bille, Bjerregaard and Sorensen, 2015, p.32).

Our exposition allows us to challenge Mark Dorrian’s (2014, p.188) notion of atmospheric manipulations, which he identifies as the ‘ideological aspects of designed atmospheres’ that are ‘calculated to induce a feeling or mood.’ Such designed atmospheres are often the outcome of top-down decisions and policies, he states, to condition and control phenomena like consumer behavior and work culture. Instead of atmospheric manipulation, we suggest that the term atmospheric staging is much more applicable. In doing so, we built on Gerard Böhme’s (1993; 2017; see also Bille, Bjerregaard and Sorensen, 2015) inherently kinder, slightly performative, and generally more comprehensive conceptualisation. Our exposition examines and aims to approximate how the atmosphere in the recently renovated newsroom comes about in interactions with historical artefacts (statues, paintings, symbols, archaic machinery, non-functional details of the space’s original historical design) along with other purpose-built commodities that are integrated into its spatial configuration.

As outlined by Le Cam (2015, p.35), the intersection between space and journalistic work practices can be indicative of professional and hierarchical relationships, economic and editorial strategies, production processes, and working conditions. This inquiry into the organisation and ideological reasoning behind the physical workplace, in conjunction with a focus on how the space is perceived, lived and co-created, contributes to an understanding of the affordances and constraints that journalists experience when inhabiting the newsroom on an everyday basis. ‘Built spaces are produced in practices’ (Reh and Temel, 2014, p.168), which is also true for journalism. Stronger yet, as Deuze and Witschge (2020, p.62) suggest, journalism is in a process of permanent and continuous becoming: ‘It is a highly dynamic, exciting, precarious, fragmented, networked, diversified, and at times perilous profession in the process of constantly reinventing itself.’