Monica van der Haagen-Wulff and Paschal Daantos Berry: “Diasporic-Transnational-Migrant-Bodies"

Monica and Paschal spoke about the difficulties of communicating via video conferencing, in particular how it meant both bodily presence and absence in space and time in the rehearsals and the final performance. How is it possible to perform the Other in absence and how do you perform the remnant of that dialogic exchange? How does displacement, in this case, as existing in a virtual space in real time rather than face-to-face in time and space, indicate and constitute transnational and diasporic experience? They also discussed how the politics of desire and commerce are co-opted and negotiated into a transnational culture of music, poetry, literature, and politics of the immigrant, the exiled, and the refugee. In terms of diasporic and transnational engagement, they asked what it means not to be able to perform what is in your body — due to multiple transcultural embodiments — when the nature of the gaze anchored in discourse relegates that which wishes to express itself, as self, to the hidden, secret, problematic, unwanted, and invisible? How do you renegotiate or repatriate that which has become inscribed in your body? Which bodies are authorised to carry what cultural knowledges? Who holds the power to decide? What gets erased when you can’t bear the tension and discomfort around historical guilt? In Monica’s case, does decolonising her body mean repatriating that which she is perceived to have stolen? Can movement, dance vocabulary, stories, memories, knowledge constructions, touch, relationship, love, and connections that make up ‘who I am’ (an identity) be removed? What happens to the Filipino diasporic artistic body when it doesn’t meet dominant heteronormative and racial expectations? Can the exclusionary violence of hegemonic borders, contained in binary opposites of one or the other, feminine/masculine, black/white, traditional/modern, authentic/fake, coloniser/colonised and so on be decentred and decolonised by a strategy of shape-shifting and acts of cultural and gender piracy, as demonstrated in the work of Filipino performance artist Caroline Garcia? Does Monica’s engagement in this project as a white woman from the Global North, with the embodied Asian cultural knowledges it contains, make Paschal’s Filipino-Australian embodied Asian and other knowledges invisible in our engagement?

Michael Lazar and Sari Khoury: “Bodies in Time and Space”

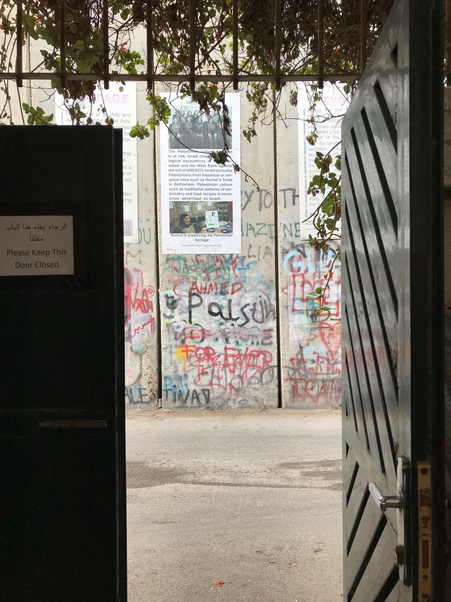

Michael and Sari reflected on how the freedom of movement of a body changes from one place to the next within a continent, country, or city; how hegemonic body structures vary from one area to the next; what parameters are responsible for these changes; and how the body reacts and deals with them. These ‘borders’ are often physical realities, but they are also often psychological — put in place by our minds as a type of defence mechanism. Coming from a ‘privileged’ sector of Israeli society, Michael was faced with the realisation of the extent of external and internal (embodied) borders that his Palestinian video partner Sari had to negotiate in his everyday existence. The knowledge gained from the conversation did something profound to Michael’s body and his own experience of time, place, and mobility within the privileged international Cologne rehearsal space. He illustrated this by showing the group two sets of pictures. The first was the view outside of his dorm window: the vast green forest of Remscheid, which spread out in endless nature. The second was that of what his video partner, Sari, saw when he looked out his window: three tall, imposing walls that surround his home which were meant to keep him and ‘his kind’ in. Sari mentioned that he was also privileged, holding the ‘right’ kind of identity card that let him skip the long lines at the border between Palestine and Israel to get to work. And yet he was often held up for hours for no particular reason, and thus, often late for important meetings. Once across the border, he was forever looking over his shoulder, anticipating the soldier that would demand to see his papers.

Here were two people with similar, yet vastly different backgrounds: both very well-educated professionals around the same age. Under different circumstances, as Sari pointed out, they might even have been friends and not ‘enemies’. Just by having served in the army (obligatory in Israel), Michael automatically belonged to the oppressor, regardless of his political views. And yet, Michael’s family was in the role of the oppressed only 70 years before, when they had been rounded up and murdered by Hitler’s Nazi regime.

Michael played on this theme of the wall and invisible borders, raising questions within the performance of who has the right to go where (and who decides) and what this does to the body.

Ciraj Rassool and Dierk Schmidt: “The Racialised Body and the Museum”

THE TASK for the interdisciplinary performance team, as they gathered near Cologne to work together for six days, was to come up with their own specific topic related to bodies and their location within hegemonic structures and to choose a suitable partner for video conversations with experience in the chosen discourse. Each participant was asked to decide, reflect, and write about bodily exclusion and the context (the discourse that excludes) that they would like to engage with. The aim was to facilitate a conversation on a level playing field with a video partner interested in holding the conversation and willing to be a collaborator and thus actively involved in shaping the outcome. We were searching for a structure that would enable an effective collaborative relationship not based on a researcher/subject model. By working across the boundaries of theory and practice within a transdisciplinary framework, we were attempting to decolonise the practitioner/expert relationship, instead basing the video conversations on relationships of integrity, mutual interest in a dialogically resonating engagement, and common ownership of the final performance outcome. This also meant negotiating modes of working together and establishing in advance how much visibility the partners would like in the experimental transfer. To what degree we could achieve this goal was part of what we were interested in exploring across a transnational digital divide.

Dr. Monica van der Haagen-Wulff (concept devisor, project co-ordinator, scholar/performer)

Dr. Fabian Chyle (concept devisor, scholar/performer)

Prof. Dr. Ciraj Rassool (scholar/performer)

Kelvin Kilonzo (actor/dancer/performer)

Dr. Michael Lazar (scientist/artist/performer)

Arahmaiani (activist/artist/performer)

Ciraj spoke about how his conversations with Dierk were built upon a friendship and several years of collaboration on colonial entangled histories and the cultural politics of museum collections of human remains in Germany and southern Africa. This was an engagement with histories of dispossession, theft, and scientisation, as well as the incorporation of the stolen bodies of twentieth-century persons into the museum collections and research mobilised by racial science. This history of colonial violence marked the museum in its very organisation and disciplinary nature, and sat alongside other histories of violence that the museum was implicated in. While the work of decolonisation was happening on many fronts, the activism around human remains repatriation sought to address a core aspect of the modern museum’s history. These matters couldn’t be addressed effectively only through collections management and provenance research. They needed a wider interrogation of the museum itself and its categories, and how perhaps the modern museum itself needed to be fundamentally rethought. As an activist and artist, Dierk Schmidt’s work was an interrogation of colonial history and the museum, with a focus on the Berlin Conference of 1884 and on the vitrine as a signifier of the museum as epistemology.

Fabian Chyle and Kris Larsen: “The Body and Institutional Violence”

Fabian and Kris’ research covered different aspects of institutional power and violence and their relation to the bodies present within those structures. The topics and questions they asked themselves and discussed during their video conversations were:

- The bodies of limitations: how do institutional structures construct bodily patterns? How do environmental conditions, such as being locked up, inhabiting small spaces, or living in an extremely physically penetrating world of bodily smells, influence the ‘bodily self’?

- Placing new experience and memories next to each other: how can the artistic and physical work of dance/movement therapy influence the inner balance of a body by creating new experiences?

- What are the different forms of otherness, such as being black, gay, mentally ill, the client, or the therapist?

- Equality of relationship (which is something that dance/movement therapy tries to construct in the work): how do we work as being part of a minority group with members of other minority groups? What happens to the relationship, considering the fact that we are part of the staff?

- How does the implicit or explicit promise of a cure create a power relationship and how is this embodied?

- Who do we meet when we meet the clients? Themselves? The institutional adaptation? The disease?

- How can we work with dance and movement within institutional restrictions? Especially as these are, in this context, subversive media, going against the rules and laws of an institution (interesting for a university performance-conference).

These topics surfaced while speaking about their common memories of working at St. Elizabeth Hospital (Washington D.C.) and being part of the institutional structures of the mental health system. Their conversations were based on forms of dialogue not necessarily open to physical and associative realms. In their conversations, they were therefore exploring other means of exchanging experience.

Arahmaiani and Gunnar Stange: “The Body as a Target”

A glimpse into the second video conversation, during which Fabian and Kris only used questions to communicate.

1. Am I my body?

2. Are you your body?

3. What is the body?

4. Is the body the outer edge of the internal spirit?

5. When we say embodiment, are we embodying the soul of who we are or the fact that we have hands?

6. Or the fact that these hands are mine?

7. I wonder if that object that we live in is only there so I know that this is me?

8. If someone slaps me on the face — which is slapping me on the body — it hurts! But what happened in the relationship hurts more?

9. If someone makes love to me, there is the bodily experience of it, but there is something about love that I feel ... that I wonder if this my body that I feel or is it my body that is feeling IT?

10. My body contains experience, but I am not the experience! Am I excluding my own body by that?

11. Can I overcome bodily experience?

12. If I shut up long enough will I be able to really shut up?

13. When I move ... to what do I really reach out physically?

14. Is there an inner part of my bodyself which is untouchable?

15. Can I think of the other when I think the other is a body?

16. Is my body the container of my suffering or is my body the suffering itself?

17. As my body grows old, does it exclude me from my history, my childhood, my adolescent?

18. Is my body, then, a premium excluder?

19. Who do I see when I look at you?

20. Who do I see when I look at your body?

21. What does my body do when I look at you?

22. What does my body could potentially mean to you?

23. Can my body relate to my dog?

24. How can it be that other bodies immediately cause shame in my body?

25. If I were to go blind, would I still be able to experience you?

26. What about dead bodies? Or the bodies of former generations?

27. -– and those which are incorporated in our bodies?

28. Is this incorporation a form of body inclusion?

29. Why is it that when I have an itch and I scratch, the itch moves all around?

30. Does my body need the social surrounding — the embeddedness in a collective .... or ... who needs it? .... who the fuck needs it?

31. Is my body here just to eat and shit?

32. Is it a transformer?

33. A transformation machine?

34. A metabolic energised transformation machine?

35. Why is it that we spend so much time wondering about our bodies?

36. Why is it that we spend so much time wondering about other bodies ... or ... the bodies of the other?

37. If I could not use my body would you still want me?

38. If you could not use your body would I still want you?

39. If you could not use your body would you still want me?

40. If your body falls apart do I feel bad for you?

41. Do I get caught up in fear of losing control of my body?

42. How do we know that our connection is not a one-way street?

43. Can I re-humanise my body?

44. Do I want to humanise my body when humanising is so fucked up?

45. As my body is determined to die, does this imply that death always plays a role between me and other bodies?

46. Does death being a destructive act in my body imply that destructive acts are always happening between me and others?

47. If my body wants to be held, does it mean that I hold on?

48. Do I lose the sensibility of touch when I am touched more often and often and often?

49. Do I lose the sense of uniqueness of bodies meeting when I meet a lot of bodies?

50. How many imprints of other bodies can my body take in in a lifetime?

51. Is my body a library for the many imprints of my life?

52. Do I hate your body because of your imprints?

53. Do I not understand your body because of your imprints?

54. Am I afraid of your body because your imprints bring up an imprint that I do not want to see?

55. How Do I ask you to love me for my imprints?

56. Is my physical behaviour based on my imprints, and can I become more than just my physical behaviour?

57. When I become more of my physical behaviour, do I have to let go of my sensations and feelings?

58. Is my inner body a reflection of the constant interplay between victims and perpetrators?

59. Is my inner body a reflection of an outside battlefield?

Kelvin Kilonzo and Lea Gulditte Hestelund: “Bodies in Transformation - Gender, Race and Civic Belonging”

In their video conversations, Arahmaiani and Gunnar discussed the many negative effects of labelling cultures as traditional (or not modern), as they are considered to be left behind and irrelevant to this day and age. Their usefulness for the global North, which by contrast marks itself as modern and enlightened, lies in their ability to become an exotic commodity within the tourism industry. Their main function is to provide the sensual experience of an imagined adventurous sojourn into a different world, or an extraordinary experience that can be commodified and sold. Those providing this service can be likened to ‘traditional artists’ crafting unique artefacts from another world. A living museum is constructed, to be enjoyed and consumed by those privileged mobile classes for a one-off holiday or even as a retirement destination. This kind of commodity spectacle can be seen taking place in cultural tourism locations such as Bali, a process that is mirrored in an art world dominated by the market economy, in which the artwork is commodified and sold as an expensive handicraft. This is an example of how large corporations operate and how individuals become their pawns.

Both Arahmaiani and Gunar believe that this way of thinking, along with the capitalist system that continues to develop and increase in complexity (today known as neoliberalism), is the root of the problem. Aramaiani and Gunar discussed how the body is viewed and treated in an inhumane way as a result of this kind of thinking, shaped by a system of neoliberal convictions, not to mention older notions within religions that regard bodies as the source of danger and violence. However, the basic assumption of each, although one speaks in the name of religion and the other according to an economic system, are basically the same. The body is an object in such a way that it becomes a target, either for economic gain or religious conviction and/or belief in God. In this devalued state, the body can be tortured or even destroyed completely.

Kelvin and his video partner Lea spoke about their individual experiences of embodiment and bodily transformations, how their bodies were read from the outside and mirrored back to them, and the impact this had on their lives. Lea, a sculptor who has worked on shaping and reconstructing various materials, has also reshaped her own female body through rigorous bodybuilding aspiring to the physical attributes of ancient Olympic statues. She spoke about how her role in society visibly changed through this process and how she was confronted with many critical questions and sexist insults. Kelvin spoke of his experience of being a member of several track and field clubs and a basketball team throughout his childhood and youth and that although he was comfortable with his physical appearance and performance as an athlete, the physical marker of not having body hair and being black, represented a visible difference to his teammates. His perceived otherness often led to inappropriate, discriminating comments and confrontations with opponents, teammates and coaches, irrespective of his performance on the field. Lea and Kelvin researched how bodies matter to society and how they are transformed. Kelvin spoke about the possibility of transformation initiated from the self as an impossibility and how he was always already read and judged from the outside. In his own words: ‘I can’t see myself from the outside, I never think about being black, but I get it mirrored from the outside every day’. In terms of being acknowledged as an actor and dancer in his working life, he often found that when he was successful in getting a role, he was told he got the role because of his being black. If he was unsuccessful, however, it was not because of racism but because he wasn’t talented enough. He also spoke of the difficulty of getting genuine acknowledgement for his skills and achievements as an actor and dancer.

They asked themselves some of the following questions:

What does society allow my body to look like? What are the consequences of not following societal expectations in terms of physical appearance? Which clothes are appropriate, safe or dangerous for which bodies? How do these societal, normative expectations impact on work, love-life, education, community, safety, and health? How are bodies transformed for material profit, privilege, wanting to be the same, wanting to be different? How are bodies transformed through natural aging processes, weight gain/loss, wrinkles, hair loss etc. and what does that do? What are some of the interventions, skin bleaching, plastic surgery, steroids, solarium browning, tattoos and piercings, and what does that say about our desires and societal aspirations?