Gediminas Karoblis1, Sigurd Johan Heide2, Marit Stranden1,2, Siri Mæland1,2, Egil Bakka1,2

1: Program for Dance Studies, Department of Music, NTNU 2: Norwegian Centre for Traditional Music and Dance

Advanced, artistic use of folkdance is a new field of Norwegian dance art, searching for a profile, which includes participatory elements. Performer - audience interaction is a potential which seems to be particularly applicable and near at hand for folkdance. An artistically viable break through would represent a crucial innovation for folk dance as dance art. The challenge is to find techniques that reduce the performer - audience split. They should enable all participants in an

artistic event to experience one's own and other's bodily movements

merged and shared. The project assumes that the conventional stage

is a hinder for a fuller artistic explication of folk dance. Therefore, as

a point of departure we claim that folk dancing should be felt, touched,

danced and experienced from close enough distance to use the

tactile, kinaesthetic senses in addition to vision. This approach

contrasts with the idea of a performance setting the audience at a

distance of 10-100 meters as in ordinary dance theatres where stage

and audience are explicitly and intentionally separated. Performer-audience interaction is in principle an attractive aim for an artistic production, but seems difficult to solve with sufficient artistic quality and sophistication – and in such a way as to manifest clear difference from usual forms of social dancing.

In a long historical perspective the mainstream western dance art grew out of participatory dancing. It gradually liberated itself from such roots and left behind restraining conventions, but probably also unused artistic potential. The clean-cut performer - public split, for example, silenced the artistic potential which could have been found in audience participation.

In Norway new branches of professional dance art built upon other kinds of trainings and basic techniques than what mainstream western dance art educations offer. During the last decade at least 20 new professional dance works based on folk dance were created. Professional ensembles including "Frikar", Kartellet, Villniss and a good number of professional theatre productions have used folk dance as basis or a substantial element. The number of professional, free-lance folk dancers, is increasing. There are also other artistic developments in the same direction in Norway, such as the Tabanka crew, a dance ensemble aiming to base its techniques and training on Afro-American and African dance heritage. An education for performing folk dancers is under establishment at NTNU, and for that purpose we feel a need to critically explore and discuss the technical basis for and the artistic profile of the new education (Mæland, 2014).

To respond to these changes in the field of professionalising folk

dance the staff at the Dance Studies Program at Norwegian University

of Science and Technology applied for a project with the title

"Performer-audience interaction: a potential for dance art".

A larger group was established to carry the project through.

The main aspects of the artistic research process and the results of

the project are presented in this article and have also been presented

in a range of conferences. The structure of the article corresponds to

the temporal and structural phases of the project.

The project had four phases:

1) An inquiry into existing practices of performer-audience interaction in dance art and related fields based on academic literature; support from colleagues internationally; web and YouTube searches. At this phase the project staff has also profited by pre-project explorations of the same topic. To sum up, two lines of exploration – theoretical and practical were developed in parallel. In this way they are also presented in the article.

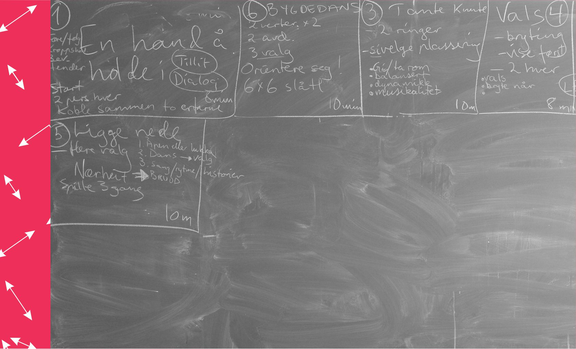

2) A brainstorming seminar was held with attendance of three invited experts from abroad. The external guests were choreographers and dancers specialised in using folk dance as their material, all also with academic background from the field. Members of the broader local academic environment of NTNU and the Norwegian Centre for Traditional Music and Dance were also invited. The aim was to analyse artistic validity and practical feasibility for performer-audience interaction within folkdance.

3) A testing of performer-audience interactivity in a small and a medium scaled artistic event, drawing upon the advanced folk dancers closely connected to Trondheim folk dance environment and its educations and projects.

4) A paper that encircles all temporal and structural parts and aspects of the project into one motion including the performance, the critical assessments and reflections from all participants as well as from audience members. The paper is illustrated with photos and video clips.

Through the twentieth century inspired by the idea of performative-interventional presentation, modernist artists in many ways explored potential of performance-audience interaction (Fischer-Lichte 2008). The interaction has been central in such art movements as Dadaism and, later, in 1960s, to artists of "happening" such as Alan Kaprow or George Mačiūnas (Fluxus) in New York. It is not by chance that Richard Schechner created the first performance studies program in New York University. Significant input to new expressions in dance choreography by Judson Church Dance Group should also be mentioned here. In many contries, starting from the United States, such approach has led to the rise of performance studies (Jackson 2004).

The interventionist aspect of art was intensively and broadly tested by performing artists and scholars. Aspects of the participatory were, however, not so much forefronted, not any necessary part in performance art, and dance was not necessarily at the core. In contrast, for example Augusto Boal's "Theatre of the Oppressed" was using therapeutic and artistic tools to address community and served a political cause to become a true inspiration. It is a technique where the audience becomes active, and it is a strong example of audience engagement. Boal's attempts to bring his theatre technique into Europe and USA have been criticised by claims that it is not transferable to communities without open and brutal oppression. As pure technique it may, however, give interesting perspectives (Schutzman 1990).

It is well known that the use of folk dance for conventional staging grew particularly popular after World War II, mainly following examples from Igor Moiseev Folk Dance Ensemble (Shay 2002; 2013). After trials to establish himself as modernist choreographer, Moiseev took so called „character dance“ in ballet as a point of departure for his choreographic innovation. He trained his dancers in classical ballet technique and staged dynamic and exalted choreographic suites based on folk dance motives and images. Thus folk dance in the Soviet Union and the Soviet bloc countries, apart from its usefulness in mass choreographies celebrating nation or fraternity of nations, became tied to balletic tradition and education. In these countries due to the condemnation of modernist dance and resulting ideological pressure young choreographers and dancers were forced to move into the field of folk dance. Some of them were looking for ways of choreographing that promotes the traditional folk dance. Until recent decades, however, folk dance, remained fundamentally separated from modernist explorations and aesthetics, in particular addressing small groups of audience. Due to the importance of participatory aspect in traditional form of folk dancing (Bakka 2007, Nahachewsky 1995), it is most likely that explorations of this approach will have a ground breaking effect for the work with folk dance as art. This may be true not only in Norway, but in other parts of the world where folk dance choreographers also seek for new forms of artistic expression.

An overwhelming material on performer-audience interaction was browsed during the early stages of the project. A review of such material, academic or artistic, in text, pictures or videos is beyond the scope of the project. It was used as a source of inspiration. Our search showed us that most thinkable techniques have already been tried in different genres of dramatic art. The innovative contribution of the project lies in the adaptation of ideas to a concrete purpose and material, and the project sees it equally important to look for inspiration from practices outside of what has already been dealt with in arts and academic studies of art. The point then is to look at mechanism and techniques applied even for totally other purposes or in other contexts than the theatre. What mechanisms are at work in such phenomena as flashmob or at pop concerts, or in the services of some Christian congregations? Interaction is clearly sought for and obtained when people are exposed to a flashmob, when congregations sing along, clap and dance. One may also look at very small scale systems where a performer meets one person at a time. Phenomena such as taxidancing and lapdancing are frequently practiced examples of such techniques, and the principle has also been used in performances.

Choreographer: Sigurd Johan Heide

Dancers: Inga Myhr, Sina Myhr, Vegar Vårdal, Marit Stranden, Asgeir Heimdal, Gro Marie Svidal, Agnar Olsen, Sigrun Dyvik Berstad, Dina Bruun Arnesen, Nina Sølsnes

The brainstroming seminar collected a big group of choreographers, dancers and

researchers of traditional dances from many places of the world. The participants

addressed the question of performer-audience interaction with openness and enthusiasm.

Music-dance relationship, the impact of live music on dance, the dialogic relationship between dancer and musician were among the main questions discussed. Sensuality of dance, intimacy and bodily intelligence were discussed as important aspects of dance in the early 21st century. These are aspects stressed by genres derived from western theatre dance, but also relevant on the folk dance scene. Researchers presented their thoughts from a roundtable held in Limerick (July 25, 2012) “How performer-spectator relationship affects private and public place distinction” (Bakka et al 2012). Choreographers shared their experience in dealing with challenges such as constructing clear rules, building trust, involving and educating audience, monitoring and overcoming scary or uncomfortable moments. Tools proposed were negotiating personal privacy for audience members, developing different levels of their engagement, managing their feeling of risks and letting them decide about participation or giving them options. The choosing of performance locations and of movement sequences were also among proposed tools, as well as ways of leading and guiding audience members individually.

The parameters of audience structure were also taken into account: is it a large, small or middle-size group, should they be treated as a group or rather as individuals, what sex and age are they? The same question obviously applies to performers: should they preferably be young professional dancers or the most suitable dancers for this particular project? It was also noted that performer-audience interaction requires quite specific social and empathic skills from the performers. The participants of the seminar noted that most folk dancers have already developed these skills, they would only need to adjust them for artistic purposes. One of the final remarks pointed to the importance of having a host in such an event.

The experiences from two pre-project interactive performances and a brain storming seminar were used to search for and select methods to be tested in experiments on performer audience interactions with traditional dance. The project did not plan a final performance, but the possibility to test the developed methods arose for the participants because of an international conference Dance ACTions, the joint conference of the Nordic Forum for Dance Research (NOFOD) and the Society of Dance History Scholars (SDHS) in Trondheim. The performance was titled “Together” and was given at 20:00-21:00 and 21:30-22:30, Monday 10th June, 2013 (Hotel Gildevangen dance hall).

The choreographer, dancers and musician researched practically for four days in February and one day before the performance in June. In addition Nils Boberg’s light design added an affective mood in the dance hall. Most of the dances/ ideas tried out were kept, but some suggestions were left behind for different reasons. Some ideas did not fit with the numerous conference members and needed adjustments. To prepare the dancers for all possible audience reactions, a big part of the exploring was by role-playing games. Some dancers got tasks to act like an intrusive person, a person who resist joining, a person who have another distinct way of dancing, a person more busy with chatting and looking at other couples etc. The dancers got some experience in how to be attentive to the reactions and tried different ways to deal with them. To practice dancing among the audience placed at the dance floor, chairs were placed to represent the volume of people. The separate pieces of dances were tried on voluntary dancers and non-dancers (students, researchers, folk dancers, old and young persons) after the first four days. This gave the dancers important experience in trying the techniques on new audience.

Here follows some theoretically grounded reflections on the underlying structure and perceptions in the Suite “Together”. Reflections are illustrated by video clips on the right side of the text.

An audience of 30 individuals are waiting in the foyer, next to the entrance door for the performance hall. At the announced starting time the choreographer addresses the audience and gives an introduction to what will happen during the performance. He explains the contract he want them to accept, the rules that will be followed. They can leave the performance at any time. They will be invited to participate in moving or dancing. Nothing will be demanding and, no particular skill is expected from them, and they can decline any invitation. The audience will not be addressed as a group throughout the performance, each member of the audience will be treated and addressed only individually.

Intro – “A Hand to Hold” and Tante Knute (Traditional Norwegian game)

– A choreographer must always ask him/herself how to start a dance

performance. Should performers appear from the backstage? Should they be

already in place? As the main idea of this performance is closeness between

performers and audience, the choreographer choses a tactile introduction.

Performers literally come to the audience, take them by hand and lead to the

space of performance. It is performed in a very gentle way. Each performer

invites two audience members at the time, takes one in each hand and leads

them calmly into the hall and on to the dance floor, placing them in groups starting them off in the game. In this way everybody is participating and no one is only watching. The audience recognizes thew game as a widespread folk dance motive. Nevertheless, the folk dance is framed in the consciousness of the audience anticipating the performance. Hence comes the feeling of the difference: it is not a folk dance party, but rather strictly framed artistic event. On one hand it promises the audience certain qualities of experience and on the other hand challenges participants by offering them to step out of the state of passive observation. This start also allows them to experience themselves as being a part of the whole performance – the action.

Halling – they kick close to my nose!

– The dancers in gentle wordless movements reorganise the audience into

smaller groups across the dance floor. They perform movements very close,

nearly touching audience members. The choreographic idea behind can be

connected to neuroscientific research which shows that tactile and visual

systems of human brain are not completely separate. Certain spaces very close

to the body are “represented by bimodal, visual-tactile neurons....The visual

receptive fields are usually adjacent to the tactile ones and extend outward

from the skin about 20 cm” (Graziano & Gross 1995, 1021). Therefore when

a dancer approaches an audience member within this range, then the member experiences a different feeling of the dance rather than just observing it from a longer distance. An audience member is not expected to dance, but find her/himself in a position between an actively involved dancer and a safely distanced passive observer.

Suldal springar – Try it in couples!

– Professional dancers perform Norwegian traditional old couple dance in a

simplified playful version with improvisations. Then gradually they pick up

members from audience and facilitate both learning and enjoying dance. The

step patterns are only a totally free mixture of simple running and skipping

which even untrained people grasp and master immediately. Still the patterns

are not simple in a way that make them monotonous and boring. Great

importance is given to softness of relationship between leading dancers and

following audience members. For a professional to lead means also in a certain

sense to follow, since those for whom this dance is totally new need more time and space in getting the ideas, patterns and in realising themselves. However, eventually even these roles can be switched and some of audience members might forget that cautious initial phase of adjustment and trial. Everybody can enjoy svikt and curves of Springar. Gender roles are downplayed, although one should admit that it may not always happen very easily. After trying the dance together with a performer, the audience members are paired and left on their own to continue playing and improvising together. A dance most of them did not know a few minutes ago is working out for them with a lot of fun. This allows the performers to invite new audience into trying the dance, and in the end almost the whole audience is activated into dancing. The overall aesthetic aim of the dance is perception of shared movement and trust.

The Waltz – Flight or Fight!

- This is perhaps the most interesting, exciting and funny part of the Suite.

The dancers first show audience the idea and later invite audience members

one by one to try out the choreographic idea themselves. The idea is the

following. The couples dance to the music of the waltz with a low point of

gravity. Suddenly the partners on the initiative from one of them change their

bodily interaction from the “flight” of a peaceful and circular waltz into a

tense, wrestling “fight” and resistance (the choreographer refers to the

traditional Norwegian wrestling). When the audience observes the dance

suddenly changing from flight to fight it evokes reactions of surprise and

amusement. And this is precisely because (1) wrestling is very much out of place in the stereotype of the waltz (2) the image of wrestling gives the dancers as well as the audiences associations to their experiences of bodily misunderstandings.It could be seen as a metaphore for the negotiations of power in social dancing as well as in life in general. The dance thematises fluent as opposed to resisting co-corporeality. Finally, audience members can try how it works themselves. The mood slightly changes between shared fun to kinesthetic work. An important consequence of this piece is the realisation of common and simple folk dance in such a way that the dance brings to the fore the most meaningful life issues and holds the sway of closeness and interaction between perfomers and audience at the same time. Also in this dance the audience are paired with each other after trying the dance with a performer for a short time.

“Lying on the floor”

– Audience is guided wordlessly to lie of the floor. The changed perspective

again thematises tactile and auditive experience particularly for those who

chose to closed their eyes. Like in the second dance of the Suite, dancers

haptically (Graziano & Gross 1995) feels so close as to give an almost tactile

experience of the air moved by their bodies. It could be quite scary if one has

the eyes closed and did not trust the dancer’s precision. Acoustic experience

also changes: the musician is moving among audience members and one can

hear the music approaching or moving away. Last, but not least, if one opens

one‘s eyes, one has an angle of visual observation completely different from

a usual one: the floor is not visible, shadow details on ceiling appear inviting to

explore them, other audience members „vanish“ from the horizon, dancers

appear incredibly big and non-proportional in presentation of the part of their bodies (i.e. big foot, small head – the reverse of how one sees one‘s own body). However, to experience these adumbrations one needs to change an attitude and focus from previous knowledge of how things are to given appearances. The dancers amplify the impression of being big by stretching out arms horizontally. It is important not to stamp on the floor (a traditional way of marking the rhythm in Norwegian traditional dance) since this sound is disturbingly loud for the audience. [When exploring the possibilities, the dancers were improvising more, but later in discussions it was claimed that the improvising should be kept within traditional dance frames. Another idea was that each dancer should communicate orally with a single audience member; to give a choice to close eyes/ watch, to be danced for personally, to get a short story of e.g. the best dance memory of the performer, sing a song for the single audience, etc. Although it was not selected for the performance, this was an interesting idea, and dancers felt good getting in touch with the audience member.]

"The volunteered body"

– Audience are again guided without words into small clusters, sitting on the

floor back to back. Dancers perform Norwegian traditional couple dances

(bygdedans). Each couple dances their own type of dance (usually not danced

at the same floor to the same music). Then a performer approaches an audience

member and ask how he or she would like a specific dance couple, that is

pointed out, to perform – faster or slower, higher or lower etc. There is a lot of

fun in seeing how the audience member manipulates the dancers. Looking into

the genesis of this experience, one could realise that this piece of performance

thematises „the volunteered body“ – experience of another‘s body as „organ

submitted to my will“ or my body submitted to someone else’s will. Additionally,

aesthetic qualities are thematised: what is style? What is „how“ of the dance?

Finale – the closure repeats Intro in reverse

- As the main idea of this performance was close interaction between the

performers and the audience, it could hardly be closed up as a climax picture.

Like in the start, in order to stress fragility of the interaction, the choreographer

choses a tactile closure. Performers literally take the audience members by hand

and lead them out from the space of performance, into the neighbouring room.

The impression of the performance caused many different emotions. Some were crying, some were trying to understand the choreographic goal, and others felt full of joy. The feedback was given immediately after the performance by anonymously filling in the questionnaire: "Was the information on beforehand enough to make it clear what you were going to experience? Which levels of interactivity did you notice? When did you experience the peak moment in the performance? Was it scary at some time during the performance, or could you relax and enjoy it? Please feel free to give further comments here on any aspect of “Together”."

There was also the plenary discussion bringing together the performers, the choreographer, the audience members and researchers/scholars. The discussions and reflections afterwards gave important feedback. “It was exciting to watch the dancers when sitting/ lying on the floor. It gave a new perspective.” “This should also be used for theatre plays.” “It was scary in the start, but the dancers seemed trustful and I forgot in the end that I had been scared from the start.” “It was good to watch the waltz with wrestling before we were invited.” “I enjoyed the relieved feeling I experienced as a contrast after the wrestling.” “I experienced a lot of laughter and playfulness. I understood that everything is allowed when I got positive feedback for trying to interact.” “The given choices of intensity of the dancers made me focus more on intensity during the rest of the performance”. It would be interesting to make a second questionnaire after some time when the impressions are sedimented/processed.

“Together” as a choreographic piece is taking the participatory elements of the audience further than the pre-project. There are more participatory elements, and the choreography dares to include the audience even more. The audience members felt as co-choreographers of their own experience. The audience is commenting on these aspects: “To lie down on the floor, to see another aspect” (peak moment), “When [I]lie down on floor, felt like a kind of meditation for me”, “Had the opportunity to see you from another point of view, was great for me”, “Another part interested me: when asked what we wanted the dancer to do – we were making the dance – no separation between the dancer and audience”, “You promised us so much, get dizzy, could actually dance, wonderful to look at”. But others wanted even more: “Wanted something more, to dance again” or “Felt like something missed before we left – expected something more to happen”. That the audience itself co-produces the performances, as we experienced in the pre-project was also commented: “Came to both performances given: first audience a lot more pulled back from what was happening; the second much more interacting, more fun, and clapping.”

According to Sigurd Johan Heide a safe framework is needed: the more the audience knows about the framework of the performance, the safer they feel, but it shouldn‘t be too safe. That would make it boring. He compares it with going fishing or attending a football match. The framework is there, but one does not know how it will work out. Balancing frameworks and potential is important in order to experience something spontaneous.

There were few comments from the audience about unsecureness. This could of course be linked to the fact that the audience consisted of dancers or dance scholars, but these were uncommon to the frame of Norwegian folk dance. Instead they commented upon that they felt welcoming with their own background: “Possible to come as a dancer, common man, youth of the city”, “Not universal, but for everybody”. They even linked the performance to their pre-experience far away from the traditions at play: “Reminded me of the Sufi dances, ritual dance” or “The part on the floor. Minnesota – family history; became a character in a play, the Israeli star in the ceiling; looked up at this frightening big soldiers, related to feeling trapped; then turned – everybody smiled and … angels, it helped. Maybe my over-reactive imagination”. Audience responses show that “Together” managed to balance the framework and openness. Nobody commented the light, the room, the dancers behaviour, the feeling of being exploited or being unsecure.

Conclusions

It appears to be important that the choreographer has the main idea, but the freedom of an audience is also of great value. The project was meant to focus on the artistic process and explorations, it did not aim to create a final product. However, it turned out that it has created a piece of dance-art. The choreographer acknowledges that many people participated in the creative process. The starting point – traditional Norwegian dance – from which the choreographer developed the basic ideas proved to work well in interactive framework.

References

Bakka, E. M., Siri; Karoblis, Gediminas; Stranden, Marit. (2012). How performer-spectator realtionship affects private and public place distinction. Paper presented at the The 27th Symposium for the Study Group on Ethnochoreology/ 50th Anniversary of the study group, Limerick.

Boal, Augusto. Get Political: Theatre of the Oppressed. London: Pluto Press.

Fischer-Lichte, Erika. 2008 [2004]. The Transformative Power of Performance. NY: Routledge.

Graziano MSA, Gross CG. 1994. The representation of extrapersonal space: A possible role for bimodal, visual-tactile neurons. In The Cognitive Neurosciences, M.S. Gazzaniga, Ed. (MIT Press, Cambridge): 1021 -1034.

Heide, Sigurd Johan (choreographer). 2011. Å være seg selv er bevegelse. Jeg oppstår i møte med andre mennesker. (To be myself is movement. I develop in the meeting with other humans). Dancers/students: Anna Liv Gjendem, Inga Myhr, Torill Steinjord and Mathilde Øverland. Musician: Torill Aasegg. Performer-audience interaction, 7/6, 29/10, 3/11 and 12/11- 2011. Archival film: Rff Dv-cam. Norwegian Center for Traditional Music and Dance.

Hoseth, Børge. Hardstad Tidnde, 11 August 2012. (English translation by Marit Stranden).

Jackson, Shannon. 2004. Professing Performance – Theatre in the Academy from Philology to Performativity. Cambridge University Press.

Kartellet. 2012. http://kartellet.org/about-kartellet-the-cartel/ , retrieved 23rd January 2013.

Mæland, Siri. 2014. Tradisjonsdans som universitetsstudium? Prøveordning med utøvarstudium i tradisjonsdans (2009-2012). In Fiskvik, Anne and Marit Stranden (Ed.), (Re)Searching the Field. Festschrift in Honour of Egil Bakka. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget. P. 91-106.

Nahachewsky, Andriy. 1995. Participatory and Presentational Dance as Ethnochoreological Categories. Dance Research Journal 27/1: 1–15.

Okstad, Kari Margrete og Egil Bakka m. fl.. 1993. Halling frå Dalsfjorden. Undervisningsvideo, teksthefte og lyttekassett (Halling from Dalsfjorden. Video, booklet and music cassette, 2 hours, 40 pp., 30 min.) (Model for teaching material on Norwegian Regional dances with the couple dance Halling from Dalsfjorden as an example.) Rff-sentret, Trondheim.

Schutzman, Mady. 1994. Activism, therapy, or nostalgia? Theatre of the Oppressed in NYC. The Drama Review 38: 77–83.

Shay, Anthony. 2002. Choreographic Politics: State Folk Dance Companies, Representation, and Power. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Shay, Anthony. 2013. The Spectacularization of Soviet/Russian Folk Dance: Igor Moiseyev and the Invented Tradition of Staged Folk Dance. The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Ethnicity (Forthcoming).

Leif Stinnerbom, dancer and musician of Swedish folkdance, ethnologist, choreographer, director and theatre producer, Sweden

The staff:

First row (from left) Siri Mæland (1,2), Marit Stranden (1,2), Anne Margrete Fiskvik (1)

Second row (from left) Gediminas Karoblis (1), Egil Bakka (1,2), Ivar Mogstad (2)

1: Program for Dance Studies, Department of Music, NTNU

2: Norwegian Centre for Traditional Music and Dance

Our work environment is the tight cooperation between two institutions: the Program for Dance Studies at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and

the Norwegian Centre

for Traditional Music

and Dance

The cooperating

institutions thus integrate

research, academic, artistic education

and safeguarding of

Intangible Cultural Heritage.

The present project has got the support from the Norwegian Artistic Research Programme

to combine all these factors

into a work of applied

research for artistic purposes.

The intention is to search for

techniques of performer - audience interaction in folk dance as artistic genre.

Our first attempt to explore performer-audience interaction was made with the 2nd year BA students of traditional dance performance (Heide 2011). During the semester, the students had thoroughly deepened their dance knowledge, exploring details, variations and improvisations in some dance traditions. Some dances such as the solo halling, the couple halling and the pols where explored in group, while other dance forms and traditions individually. Sigurd Johan Heide and the students explored how to take these dances into a choreography, and still keep the aesthetic values and techniques from these social dance forms.

The performance was happening in the audience area. The room was semi-dark; there was some electrical lighting, and some candle light. An opening section became one of the most challenging in the performance, although as a play based on traditional dancing it seemed a great idea. The students were dancing “Halling from Dalsfjorden” in a sophisticated way. They also performed it`s uncommon aesthetics and technique that belongs to this tradition (Okstad and Bakka 1993). The students were dancing close to the audience, improvising in a way which is common in the tradition. They were dancing in couples; in the free part, they were dancing solo and greeting the persons from the audience. For audience members it seemed as if they were each one targeted by a spotlight when greeted or adressed individually by the dancers. The audience was placed in a circle, everybody could watch everybody, but then the performers broke the circle and danced for, in front of and around almost each person. Some spectators blushed or moved backwards; they felt uncomfortable, while others responded by joining in and even dancing with the performers. Performance of the same piece later in a room with a pillar suddenly evoked a different interaction. This showed that sophistication in choreography will not work if one is not also being sophisticated in the way one builds trust. The atmosphere in the room should also be "choreographed" and the audience's feeling of safety and privacy negotiated. This first attempt showed that the audience’s experience of the tension between private and public is decisive for how performer-audience interaction works. The main challenge seems to be that few people are willing to play unknown games in public. In another presentation we developed a more thorough discussion how performer-spectator relationship affects private and public place distinction (Bakka et al 2012).

Soon after Sigurd Johan Heide choreographed a new performance called "Kartellet" (2012) where the audience participated and experienced a physical collaboration between five characteristic male dancers. In “Kartellet” Heide developed the same ideas on building trust, making rules, managing risks and letting an audience decide.