Indicated by their Signatures:

Nerisa Guevara’s Elegy #8 – The Pacific Ocean

with a Postscript of Claude Boudeau’s Chaos.

By Yuan Mor’O Ocampo

When I was asked to write about what is my idea of ‘signature’, this is what I wrote: A signature could be a number, a symbol, an action, a sound, a feel – PATHOS, and ETHOS – the spirit of a culture, era, or community as manifested in its attitude and aspirations, a letter “X” – a legible depiction of someone who is illiterate, then a signature could be a thumb mark.

Nerisa Guevara’s signature in LAPSody’s 7th International Live Art and Performance Festival at the Theatre Academy (TEAK) of the University of the Arts Helsinki was a four-hour performance titled Elegy #8 – The Pacific Ocean. She was interested in the body’s relation to space as manifested here by the perceived largesse of this work, the eighth of a series, a repetition of the same theme: an elegy. Gilles Deleuze once said, and I quote: “To repeat is to behave in a certain manner, but in relation to something unique or singular which has no equivalent.” [1]

Nerisa Guevara uses a variety of media in her work, including virtual and mixed realities. There was an ambiance in Studio 2 also known as the White Box, the venue where the performance unfolded. In her projection of a four-hour image of the Pacific Ocean in Baler, Aurora Province, Nerisa displayed a place ripe with fond remembrances, longing and belonging, a simulacrum of someone and a semblance of something.

Simulacrum is a late 16th-century word derived from simulare, a Latin verb meaning to copy an image and to feign. In theatre, it was used to conjure reality on stage (there is a similarity between simulacrum and simulate).

Jean Baudrillard in his 1981 philosophical treatise Simulacra and Simulation[2], talks about the relationships between reality, signs and symbols, and society, focusing on the significations of culture and media in constructing the mechanism of the understanding of shared existence. Simulacra are representations of things that no longer have an original or had no original, while a simulation is the imitation of a real-world system over time.

In this durational piece, one could smell in the air her grief, could witness her re-tracing her solitude and navigating her sorrows. In Elegy #8, the Pacific Ocean, the Pacific Ocean may not be the real thing but it was an augmented reality to emphasize the absurdity or insubstantiality of reality. But what is the dramaturgy of the digital in relation to performance?

I took a four-day course[3] facilitated by Jokke Heikkilä, Otso Huopaniemi and Mikael Brygger that explores the complexity of Augmented Reality (AR) as both an interactive technology and as a model for or description of contemporary performance. In our hands-on exercises, we examined how this practical and conceptual tool shaped and informed the process of making performances and their reception, i.e. the experience of the spectator.

I joined the course, curious about augmented reality (AR), how it can be used in performance and how it can be performed. I wanted to know what kind of opportunity or opportunities and challenges it offers artistic research. How do we understand Live Art performances where digital technology is embedded to the point that we can no longer separate the overlapping and interfacing of the physical and the digital?

In this AR course, I encountered Vilém Flusser (1920–91), whose work notably elaborated his theory of communication. He theorized the epochal shift from what he termed "linear thinking", visual thinking embodied by digital culture. Flusser goes beyond Marshall McLuhan’s 1964 dictum that “the medium is the message” to assert that new media make new kinds of messages possible, since these new concepts and ideas that were generated open doors to possibilities (ideas) that can be formed.

“The emergence of augmented reality technologies then necessitates a consideration of the new theoretical and conceptual implications this technology enables. This is not to say that augmented reality must create new ways of thinking and making. It is possible (and not always a bad thing) to simply recreate existing conceptual and artistic paradigms using new technology.”[4]

This is a “Pandora’s box” that brings up new techniques for art creation and simultaneously provides the conditions for new conceptual domains in which art can be created and experienced. To fail to factor in the potential conceptual and artistic shifts AR can alternatively provide is to close our eyes to the opportunities possible and fathom the plethora of works made in this genre. In AR’s digital dualism, that dichotomy between the “real” and the “virtual”, I cannot categorically say that the digital has already embedded itself in the cultural landscape of the everyday life. I came from a third world country and not every household in our barrio (neighborhood) has a PC, although almost all the Barangay (village) Centers have television sets and, generally, everyone has a mobile phone.

In his book Digital Performance: A History of New Media in Theater, Dance, Performance Art, and Installation (2007), Steve Dixon described the tension created: “The artificiality or falsehood of the digital image has, therefore, limited appeal to many live artists on aesthetic, ideological and political grounds. […] The paradox that projected data bodies and alternate identities enacted in cyberspace can be viewed as being just as, or even more vital and authentic than their quotidian referents, is now a source of belief and wonder to some and a totally unpalatable conception to others”.[5]

Looking back to the avant-garde idea of unifying of art disciplines, we see that Richard Wagner was the pioneer of this idea. He invented the notion where music, theatre, poetry, design, lighting, visual art, and singing can be united and create multidisciplinary forms through theatre. He expressed this idea in 'The Artwork of the Future' (1849).

When physical and digital bodies coincide in performance, one is confronted with an old notion of the performing physical body with the newly digitized version of that body. The notion of a dichotomized view of the physical and digital must be sifted through and responded to in the moment of watching such a performance. A hyped augmented reality start-up is now using technology to create music and art pieces together with Marina Abramović. They premiered simultaneously to 50 people from the 19th to the 24th of February 2019 at Serpentine Galleries, London W2 3XA, “The Life”, which was conceived, written and performed by Marina Abramović, herself. When she premiered the piece (February 18, 2019) at the gallery, she was not there in person, or at least she's not performing live. In a video starring her 3D avatar, Abramović mentioned: "This is a really promising media".

But in Nerisa Guevara’s Elegy #8 – The Pacific Ocean, what happened was that Nerisa was still physically present in the space, performing. She just engulfed herself with augmented reality (AR) of a territorial map, a four-hour projection of the Pacific Ocean in Baler, Aurora Province. Here augmented reality (AR) did not serve as the backdrop for an elegy but became the stage for the simulacra of fond memories. Her audiences were mesmerized by the sound of the waves, calmed by the iterative simplicity of her movements and were empathizing with her displayed melancholia, conduct justified enough since it is that which cannot be replaced, a simulacrum of an endless longing for someone.

Beforehand, Jokke Heikkilä[6] told us that our four-day course on Augmented Reality (AR) is not sufficient to truly explore the complexity of the subject. For my part, I do not pretend that I am already knowledgeable, all the more an expert on the topic [DM1]. All I can say is that I have scratched the surface of the matter. It was Jokke, during our first meeting, who told us that as we examine this practical and conceptual tool, we can get overwhelmed and feel frustrated. I learned two things from him and I can quote him on that. The first was “it is not the app but the application”. The second was a word of encouragement that if ever in the four-day course of Augmented Reality (AR) I should get disheartened by the process, “it is alright, ei menny ihan niinku strömsössä”. I guess I will take these two quotes home and remember them by heart.

[1] Deleuze, Gilles. 1994. Difference and Repetition. Translated by Paul Patton. New York: Columbia University Press. 1.

[2] Baudrillard, Jean. 1981. Simulacra and Simulation. Translated by Sheila Faria Glasser. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

[3] T-VM213 - Augmented Reality: Medium or Conceptual Model? Lighting and Sound Design, Theatre Academy, Vässi (Lintulahdenkatu 3), University of the Arts Helsinki. Tuesday – Friday, February 12-15, 2019.

[4] Vincs, Kim et al. 2018. “Skin to Skin: Performing Augmented Reality”. Augmented Reality Art: From an Emerging Technology to a Novel Creative Medium. Edited by Vladimir Geroimenko. Cham: Springer. 161.

[5] Dixon, Steve. 2007. Digital Performance: A History of New Media in Theater, Dance, Performance Art, and Installation. Cambridge Massachusetts: The MIT Press. 24.

[6] Jokke Heikkilä is a Lecturer in Media and AV technology, Lighting and Sound Design, University of the Arts Helsinki.

[DM1] Daniel Merry, or an expert on the topic.

"Keep it stupid and simple." Juhani Tamminen.

But then, it has been superseded now with:

"People need simple phrases, bread, solidarity, laughter." Imre Kertész.

Words of wisdom from Juha Valkeapää.

P.S.

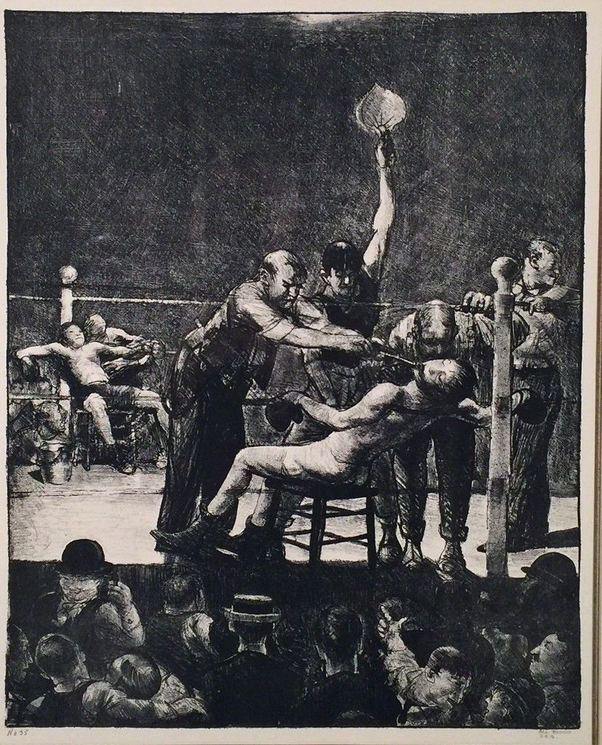

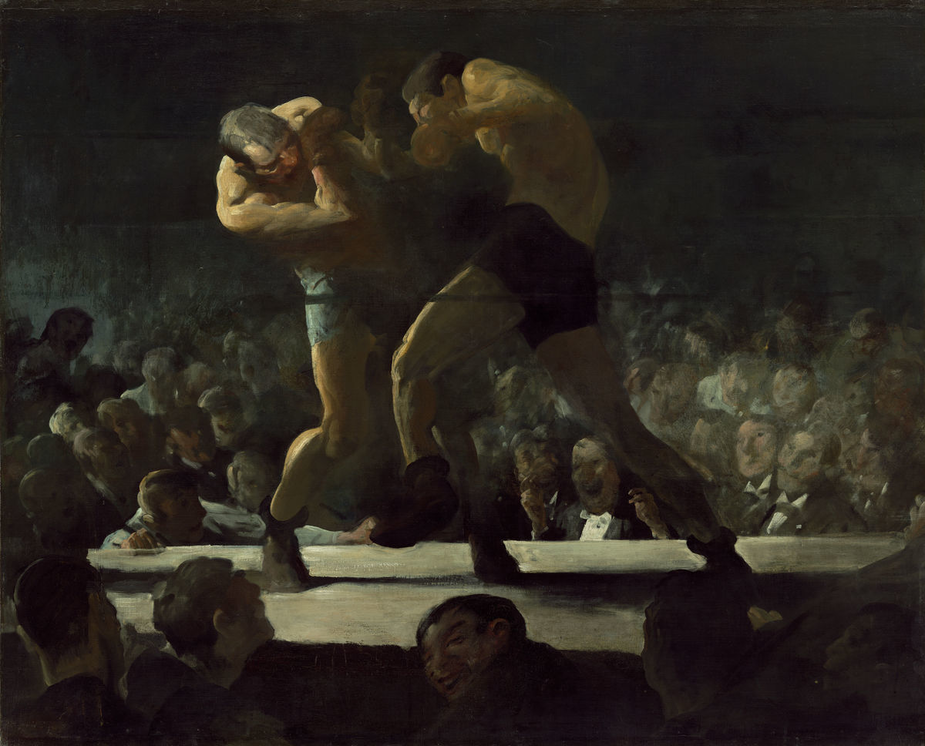

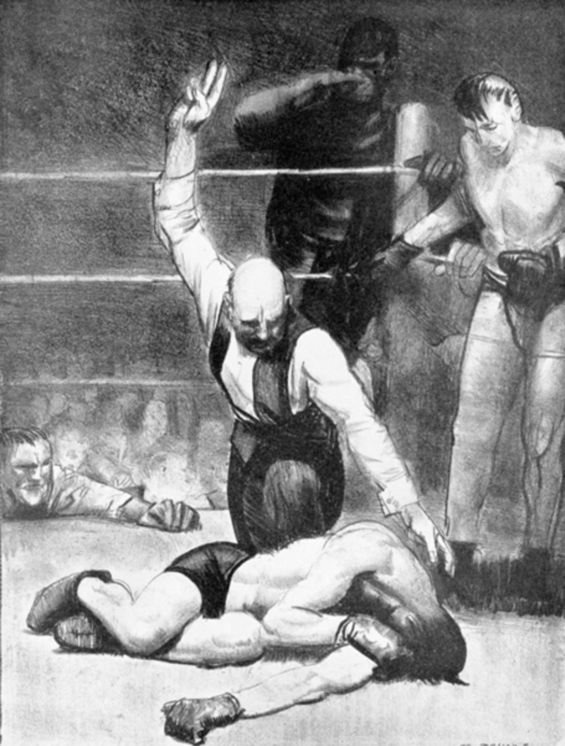

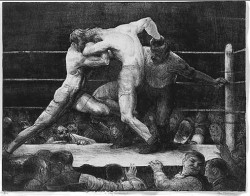

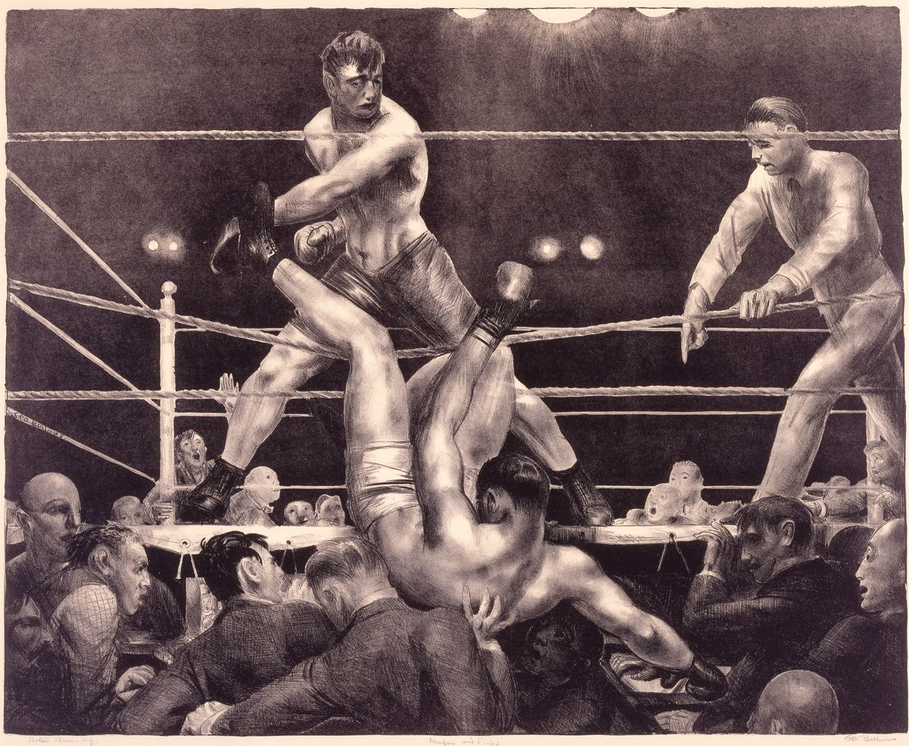

Claude Boudeau’s performance piece at LAPSody 2019 reminded me of George Bellows' works that depict boxing matches and tournaments. Bellows is an American painter and lithographer noted for his paintings of action scenes (boxing) and for his expressive portraits and seascapes. George Bellows became the leading printmaker of the Ashcan School. Dempsey and Firpo (1923–1924), was a signature lithograph by George Bellows that depicted a scene of boxing (that usually happen in dingy lit backrooms of bars in New York City), just after the turn of the 20th century.

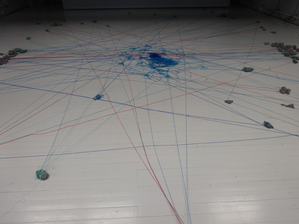

Claude’s "Chaos" evoked in me a wide range of images, from fun to gory to toxic masculinity. In my tête-à-tête with the artist who lives in Besançon, France, he told me that chaos (ˈkā-ˌäs) can also sound ‘KO’ as in knockout. The term KO is a signal that the fight is over, most especially in full-contact combat sports, such as boxing or Muay Thai, mixed martial arts, etc. The term is often associated with a sudden traumatic loss of consciousness caused by a powerful physical blow. From those repetitive strikes thrown at me by a friend, Nicolina, when we were sparring in a fighting-based video game at an amusement center somewhere in the city proper, those series of karate chops and flying kicks gave me a full KO. I was rendered incapable of continuing to play.

Toxic masculinity usually occurs largely in a vocalized language; however, it was the first impression I got from Boudeau’s opus: Chaos. What do we do when 'sensitive' issues or current issues get manifested or performed in the context of performance? What does it tell us? I reckon toxic masculinity was not the central concept of Claude Boudeau’s work, it was not even at its periphery. But, if it gets implied, I am happy that Boudeau pointed it out indirectly to us. Could he be urging us to do something about this topic and to be more conscious and aware that this is a real issue and not an augmented or virtual issue? Although during the performance I was concerned that his action-making could escalate into some kind of violent encounter, I saw that his deference to his ‘sparring partners’ was imminent.

What underlies the attraction to such violence? Why choose to depict such a subject? David Curcio in 2015 wrote an article about The Boxing Lithographs of George Bellows at The Boston Public Library:

“George Bellows said, “I don’t know anything about boxing, I am just painting two men trying to kill each other.” What underlies the attraction to such violence? […] A less pessimistic reading is of the sport as a theatre in its purest form, stripped of all artifice”. [1]

Bellows was a realist painter. His aim was to look at what was then frequently overlooked in society or by society or at least the society of that era where he lives, which was brutality: life below the radar, life below the poverty line, squalid living conditions in the backrooms of bars and alleyways, then paint and portray what he saw as honestly as possible. In his lifetime, George Bellows may have produced only a small number of boxing paintings that one can count on both hands, yet these ignominies, unscrupulousness, and depictions of ‘low-life’ became his hallmark, his distinguishing characteristic, his signature. However, he became famous not because of the spectacle these boxing paintings created or the sensation they caused but because of the artist’s gravitas in the handling of the subject.

I had this informal interview with the artist Claude Boudeau on the third day of the festival and I asked him why he titled his work Chaos? He said: “chaos (ˈkā-ˌäs) can also sound like ‘KO’”

“My two cents' worth opinion is that violence is never OK, be it actual, verbal, or implied. The audiences’ reactions during the LAPSody Festival were mixed feelings, but, unlike some of us, most were ‘captivated’ by the perpetuated actions that were going on in the blue-square-ring in the middle of Studio 2. The actions manifested by Claude engendered violence, a questionable behavior generally and it was not at all fascinating to me. Only when we introspect deeper on sensitive, difficult or not readily accepted subject matter to talk about objectively, can we begin to understand this social malaise. In this contemporary world where violence begets traits not conducive to a compassionate society that we are trying to achieve, there is no room for violence or aggression of any sort. Violence begets violence.”[2]

[1] Curcio, David. 2015. The Boxing Lithographs of George Bellows at The Boston Public Library. Boxing over Broadway. https://www.boxingoverbroadway.com/the-boxing-lithographs-of-george-bellows-at-the-boston-public-library/Accessed April 7, 2019.

[2] A concept that described Matthew 26:52 in the New International Version of the Bible.

Photo of George Wesley Bellows (1882 - 1925). The Boston Public Library

Slide #1 Between Rounds (1916). Edward T. Pollack Fine Arts

Slide #2 Both Members of This Club (1909). Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.

Slide #3 Club Night (1907). Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.

Slide #4 Counted Out (1921). The Boston Public Library

Slide #5 Preliminaries to the Bout (1916). The Boston Public Library

Slide #6 Stag at Shakey's (1909). The Boston Public Library

Slide #7 Dempsey and Firpo (1923-24). Photo by John R. Glembin. Courtesy of the Milwaukee Art Museum

Slide #8 Dempsey Through the Ropes (1923). The Boston Public Library