'Writing' as a choreographic element in Inside/Outside was drawn from the traditional plucking hand movement.

T: My teacher teach me how to perform [...] the movement, like expanded preparation, or some kinds of movement or gesture for, (what) we call communicative purpose, that we have to learn.

S: What does this communicate normally? That kind of gesture?

T: First of all, when you play music, your face should be like...

M: Fresh.

T: Yes, fresh, and should be (...) all the time smile.

M: not too much, but the smile (shows the smile...), the face looks like, very happy.

T: Happy face.

S: It should always be happy.

M: Yes (shows the correct expression...) fresh...yes, I don’t know how to explain...

S: Can you show? What does it look like?

(Both My and Thuy show the ”correct” kind of smile and a controlled happy face...)

S: When we looked at the performance with your group, we could also see this very slow preparation there...

M: It is....That was actually not the slow preparation, but after the sound when I finish something, I can (shows the movement...)

S: Yes, in the group?

M: In my group, yes.

S: aha, ok, in your group.

M: Yes, just down (shows the movement...)

S: So, is that more typical for you also to do them after?

M: Yes, just make the action more beautiful (shows the movement...)

S: Yes...

References

Clayton, M: (2007) Observing entrainment in music performance: Video-based observational analysis of Indian musicians' tanpura playing and beat marking, Musicae Scientiae 2007 11: 27

Davidson, J: (1993) Visual Perception of Performance Manner in the Movements of Solo Musicians, Psychology of Music 1993 21: 103

Davidson, J: (2007) Qualitative insights into the use of expressive body movement in solo piano performance: a case study approach, Psychology of Music 2007 35: 381

Foster, Susan Leigh: Choreographies of Gender (1998), Signs, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 1-33, University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Frisk, H., & Östersjö, S. (in press). Beyond Validity: claiming the legacy of the artist-researcher.

George, Kenneth M.: Music-Making, Ritual, and Gender in a Southeast Asian Hill Society (1993), Ethnomusicology, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 1-27, University of Illinois Press, Illinois

Godøy, R., 2006: Gestural-Sonorous Objects: embodied extensions of Schaeffer's conceptual apparatus. Organised sound, 11 (2), 149-157.

Halstead, J (2003) ‘The Night Mrs Baker Made History’: Conducting, Display and the Interruption of Masculinity in Women: a cultural review Vol. 16. No. 2.

Jensenius, A. F., 2007: Action - Sound: Developing Methods and Tools to Study Music-related Body Movement. (Oslo: University of Oslo).

Jensenius, A; Wanderley, M; Godoy R., and Leman, M(2010) Musical Gestures: Concepts and Methods in Research In Godøy and Leman (Eds) Musical Gestures. Sound Movement and Meaning (2010), Routledge, New York

Ellen Koskoff: (1987) Women and Music in Cross-Cultural Perspective, Chicago: University of Illinois Press

Langton, Rae 2009, Sexual Solipsism: Philosophical Essays on Pornography and Objectification, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leman, M: (2010) Music, Gesture and the Formation of Embodied Meaning. In Godøy and Leman (Eds) Musical Gestures. Sound Movement and Meaning (2010), Routledge, New York

Nguyen, K T: (2012) A Personal Sorrow: Cai Luong and the Politics of North and South Vietnam Asian Theatre Journal, vol. 29, no. 1 University of Hawaii Press, Hawaii.

Szymanski D, Moffitt L, Carr, E (2011): Sexual Objectification of Women: Advances to Theory and Research, sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI:10.1177/0011000010378402 http://tcp.sagepub.com

Trịnh Bách (2003): Nhã Nhạc Cung Đình Triều Nguyễn Việt Nam. Tạp chí Văn hoá xưa và nay, số 134 (tr.13-15) và số 135 (tr.24-26).

Williams, Sean: Constructing Gender in Sundanese Music (1998), Yearbook for Traditional Music, vol 30, pp 74-84, International Council for traditional music

Inside the choreography of gender

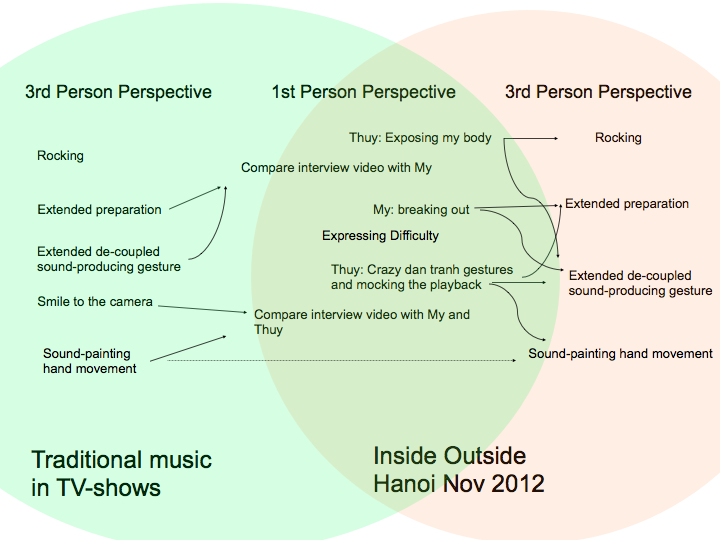

In the workshop in Malmö in August 2012 we created individual choreographies for each performer in collaboration with Marie Fahlin. Drawing on material from the analysis of gendered gesture in TV-shows, the project moved into a more subjective stage where Trà My and I, who are both part of this performance tradition that we address, could stage our individual experiences. The piece that was finished in a second series of sessions in October did not represent the expectations of any of the participating artists. What is most important for the analysis of this process and of the final choreography that we performed in Hanoi is how our understanding of the gesture is also culturally situated[1]. In order to analyze the process, it is not enough to look (and listen to) at the (musical) gesture we perform but we also need to find a way to discuss our subjective understandings of it. I will now turn to some examples of this 1st person perspective on the video documentation. But I will also attempt to identify connections between the 3rd person perspective analysis we made on the TV-shows and the final choreography. This will serve the double purposes of unpacking the conceptual layers of the piece and to provide an inside perspective on the creative process.

I now turn to an example of how the rather universal behaviour of “rocking” - normally a way to synchronize the music between performers - has been turned into a decorative element when female performers play Vietnamese traditional music. It comes out as a first example of the objectification of women’s bodies that has become characteristic of performances in TV-shows. [2] Please note also the shape of the plucking hand of the tỳ bà players. The hand movement of this sound-producing gesture became material in a section we will soon look at. In Inside/Outside, these movements were transformed into gesture that was part sound-painting and most of the time related more to writing than to plucking the strings of the tỳ bà.

The 'rocking' took several different shapes in the choreography, first as a series of shared movement sets performed in time with Dạ Cổ Hoài Lang - a traditional piece we were playing - but it also went into individual choreographies [3]. Hence, the rocking movements were sometimes decoupled from the expected sound production, and sometimes not. In my coding of the video I made the following annotation to describe my experience of performing a section of the piece where the rocking movement was further exaggerated into a communicative gesture that went beyond what you would find in a TV-show:

"I felt here like I turned my back to the camera even if the room doesn't really have a back and front... and when I performed these gestures I explicitly tried to expose my back to the camera through exaggerated sound-producing gestures and rocking."

In the clip that refers to this annotation we see three types of gesture material: exaggerated rocking gestures, rocking movements in time with the traditional piece that we played and some moments of the gesture built from the tỳ bà tremolo.

In the analysis of TV-shows we observed a lot of communicative gesture that expanded the sound-producing action. Bear in mind that these recordings are always play-back, so the gesture is sometimes also disintegrated with the sound for this reason. In this clip we can see how the soloist extends the sound producing gesture in the right hand and repeats it after the actual plucking. [4] Hence it is both extended and de-coupled from the actual soundproduction.

In one of the 'interview-sessions', Trà My and I discussed with Stefan Östersjö the way in which a student in the academy in Hanoi will be taught to express ease and look delightful and always keep a light smile while performing. Though we were very sleepy when the conversation started, I believe we did capture some of the entrained behaviours that are part and parcel of the current performance practice of traditional music in Vietnam of today. When asked to demonstrate the correct manner of smiling (to the camera or to the audience) we immediately produce a controlled but 'delightful' smile on our sleepy faces...

Trà My described quite similar intentions in her individual choreography and how, at some moments, she would think of the situation in the glass box as a metaphor for the traditional performer's context in contemporary society. This could then result in more aggressive movement types, like attempts at 'breaking out', which is how she would characterize the movement in the video below.

In both of these examples, the first person analysis pointed to some of the political significance that the gesture took on for the performers in the piece.

My attempts at approaching the musical gesture in the video from first and third person perspective has provided some insight into how meaning formation on the subjective level can be shaped in different contexts. Further, I also find that, for Trà My and myself, performing Inside/Outside became a vehicle for us to articulate a critical understanding of gendered gesture types in traditional music performance. I do not have any substantial material with which to evaluate audience reactions. However, from informal conversations, the piece appears to have spoken clearly to a Vietnamese audience while many Western viewers have been confused by the performance. I believe that this may have several reasons where one is that the formation of gender studies and feminist critic has a different history in Vietnam and in Western countries. For several reasons, outspoken critique in the manner of Western political theatre is not the typical mode of expression in Asia.

Perhaps the results of the 1st and 3rd person analyses that we have produced can also contribute to an understanding of the social function of the gesture in the music discussed. And also, taken together, the two analytical perspectives might give insights into the gendered gesture types in traditional music performance and how a resistance towards these societal norms can be expressed in artistic form. Musical gesture can indeed express, amplify or question gendered stereotypes in society. It is my hope that an artistic project like Inside/Outside can contribute to an increasing awareness of these issues in Vietnamese society.

In discussions of extended sound-producing and preparatory gestures, Trà My touched on the central aspect that in fact these actions tend to overlap. [5] She describes in the video how she would typically perform such a gesture in her traditional music group. She also expresses how the only function of these movements is decorative: 'to make the movement more beautiful'. While the general aim with musician's movements may be said to be directed towards an intended sounding result, there are numerous examples of how, in instrumental teaching in Vietnam, the visual impact of a particular gesture is at least as important as the sound.

When the audience enters into the installation space, the musicians in the glass boxes are frozen in playing positions, like objects in a museum. When the performers start playing, they would sometimes be playing for real and sometimes only be making playing gestures in the air. The sound from the instruments is diffused into a quadrophonic sound system and this displaces the sound and source. This disconnection between action and sound is further emphasized by the playing in the air. In a solo section towards the end of the piece, I expanded further on this approach in a manner that could be understood as ”mocking the playback” in the recordings for TV-shows:

Thủy: “I applied several typical gestures from đàn tranh playing to a further disconnection from the typical sound-generating action. In my mind I imagined this to be like going crazy over the situation in the glass box. [...] I first thought of this as just pretending to play, like in the opening. But then I felt that the critical stance was so much stronger here. I am not just "pretending to play" like in the play back recording for a TV-show but here I am mocking the whole situation with the disconnected hands and only one of them actually playing. The viewer's attention is drawn (I believe) to the hand that is not playing and, just as with TV-shows with traditional music, they are watching the wrong thing.”

Another visual behaviour that is specifically choreographed in TV-recordings is smiling into the camera. Since the recordings are done playback, the performers will be notified when they are in view and asked to look into the camera and smile. Sometimes this does not come out so well with the playing they are also trying to represent [6], as in this video with the same young tỳ bà players.

It was decided early on, in our working sessions with Marie Fahlin, that looking into the eyes of the audience or smiling would not be part of the choreography in Inside/Outside. In my individual analysis I described how I would take this reduction further into movement that would intentionally express difficulty in performance:

Thủy: “In this moment, I was intentionally trying to depict the difficulty facing a traditional performer, here by standing and turning around the instrument in ways that make it hard or impossible to even play. This in contrast to the otherwise typical expression of ease in traditional music performance.”

Discussion and summary

If I now return to the overview of the coding of gesture types in the 3rd person perspective and consider the subjective expressions of intention from Trà My and myself, one may conclude that the subjective meaning of a certain gesture can indeed be opposites, depending on the context and of course the intention of the individual performing it. [7] For instance, when I performed my individual choreography with the rocking material which was shaped from the idea of exposing my body, metaphorically speaking, to the camera, not only was my perception of performing this section totally different to performing similar movements on demand in a TV-show but also, the expression I intended was totally different. Similarly, even though we have seen that My would perform extended preparations and sound-producing gestures when she plays in TV-shows, when she talks about ”breaking out” of the box in relation to the exaggerated preparatory movements in the video, the contrast between the intended meaning in the two different contexts could not be bigger.

[3] The music in Inside/Outside is built with two core elements of cải lương, the two pieces Dạ Cổ Hoài Lang and Vọng Cổ. This music is deeply interlinked, where the later piece is in fact a development of the former. Dạ Cổ Hoài Lang was composed in 1918 by Cao Văn Lầu (1892–1976), also known as Sáu Lầu. In this process, Nguyễn (2012) notes how “Dạ Cổ Hoài Lang” “transformed from a two-beat version, to four-, eight-, sixteen-, thirty-two-, and sixty-four-beat versions, with the thirty-two-beat version being most commonly used today” (ibid, p 259).

[5] The fact that the various categories of sound related actions tend to blur in the course of performance is discussed further by Jensenius et al (2010). Jensenius, A; Wanderley, M; Godoy R., and Leman, M(2010) Musical Gestures: Concepts and Methods in Research In Godøy and Leman (Eds) Musical Gestures. Sound Movement and Meaning (2010), Routledge, New York

[2] At least we found that the waves of 'rocking' ty ba players in pink dresses in this video rather to be intentionally choreographed by the producer than having anything to do with communication between the players. Our impression was more like watching a group of sirens floating at sea.

[1] The process of making Inside/Outside surely emphasized how different the cultural understandings of gender issues are. Throughout the working period, Marie and Stefan were curiously trying to figure out what the core issues were and what would be the proper way to address them in artistic form in the Vietnamese context. The sessions in Malmö brought questions from the analysis into the making of the piece and with them, a sense of uncertainty of where the piece might be going. It must be admitted that this general uncertainty remained when we went into the final rehearsals and performances in Hanoi. Inside/Outside was a challenge to all of the participating artists.

[7] Obviously, the artistic method in Inside/Outside is very much built on the disconnection of action and sound which in itself creates a critical space between the layers of gesture.

[6] Trà My also refererred to a similar recording session when she was playing a sad lullaby, a piece in which, for her, the visual expression must be restrained and serious. However, the producer asked her to smile, with the rather unfortunate result that she instead made a very funny face when they started recording.