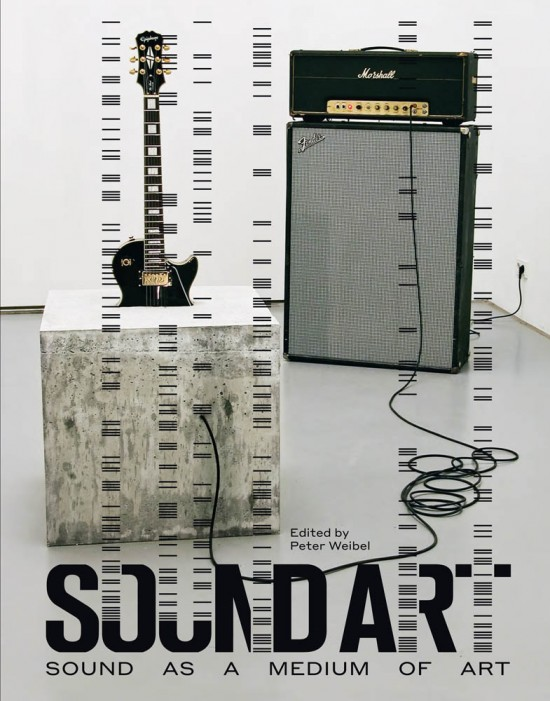

Sound Art: Sound as a Medium of Art - Peter Weibel (ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019

by Marcel Cobussen

Sound Art – Sound as a Medium of Art is a colossal book, weighing 3.5 kilos, and covering over 740 pages. The book is edited by Peter Weibel, director of the ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, Germany, and ZKM is also responsible for this publication, while MIT Press is the official distributor. ZKM and Weibel thus leave their mark on this book, which is perhaps first of all noticeable in the heart of the book: from page 162 to 458 it turns into a catalogue of the ZKM exhibition Sound Art – Klang als Medium der Kunst, which took place more than seven years ago, from March 2012 till January 2013. Around this catalogue, four sections are woven: Sound as a Medium of Art, Media Technology in Theory and Practice, Sound Art in Context, and Historical Cartography of Sound Art. These sections consist of 24 textual contributions from various sound scholars, well-known ones as well as newcomers. The texts are interspersed with plenty of images from the sound artworks under discussion. This makes the book both a rich reference work to be read and an impressive object to be looked at and into (only when your coffee table is stable and solid enough of course).

This book undeniably gives a nice overview of some 100 years of sound art, at least if one agrees with Weibel that one of the first sound artists was Luigi Russolo, who constructed his intonarumori (noise intonators) in 1913. Whereas the ZKM exhibition had a strong focus on especially German and other Northern European sound artists, the book compensates for this Eurocentrism mainly through its fifth section, also containing contributions on the development of sound art in “peripheral countries” such as Russia, Turkey, China, and Brazil. This brings me to two points of criticism: sound art in Africa seems nonexistent, at least it is neither represented nor mentioned even once in this volume. And although it may be quite remarkable that a rather substantial amount of contemporary (well, let’s say since the 1960s) sound artists are female – although a 50-50 ratio has still not been achieved – in the aforementioned countries the sound art scene consists predominantly of males. By the way, a similar observation can be made regarding the 24 contributors to this book: only five of them are female!

As with most edited volumes (including the ones I have [co-]edited myself), you can always question why certain contributions made it into the final publication. Also here, the level of information, erudition, and interesting thinking fluctuates from one chapter to the next; some are relatively uninteresting (to me), while others provided me with truly new insights. Fortunately for me, it is impracticable to review all contributions, so I allow myself to make a purely personal selection of the ones that attracted my attention the most.

In the first chapter of the first section, Weibel provides an elaborate overview of the history of sound art, starting with the acceptance of all sounds as potentially musical material, the consideration that any sound-producing object is potentially a music instrument, and the shift in emphasis from time to space in the works of several composers. People such as Luigi Russolo, Edgard Varèse, John Cage, Max Neuhaus, Bill Fontana, Alvin Lucier, and Maryanne Amacher paved the way for sound art or belong to the first generation of sound artists. (These names also reveal that it was an essentially male-dominated field at the time.) The rich collection of images accompanying this essay also makes clear that, while in sound art sound might perhaps be the most prominent parameter, it is certainly not the only one: visual and tactile elements have been profoundly important from the outset of this new art form; besides, architecture and (new) technology – one of the effects of the latter was that sometimes performers or composers could remain absent and the listener would become a participant – had a huge impact on its development.

Sound itself is to be understood as building material, as an architectural, sculptural, form-producing material – like stone, plaster, wood. (Bernhard Leitner)

Not too concerned with the chronological order of the book – I think each reader can pick and choose her own sequence; all essays can be read independently – I jump to Section 5, consisting of an (historical) overview of sound art practices in 11 countries. Being quite familiar with sound art in the UK, Germany, and the US, I was more interested in, for example, its history and current developments in China and how it would be presented in this volume by Dajuin Yao, one of the pioneers of the Chinese sound art scene. Yao’s essay begins rather provocatively by stating that, perhaps contrary to Western beliefs, China has a very long sound art tradition: treatises on sound go back as far as 10 BC, and the sixty bells excavated from the tomb of the Marquis of Zeng – meant to be buried underground forever as burial objects – were produced around 2,500 years ago and would make a compelling sound artwork today.

At the Temple of Heaven in Beijing there is a so-called Echo Wall from 1420 “to which one can whisper or talk and the sound can be heard by someone on the diametrically opposite side of the circular wall” (p. 645).

Quickly moving to contemporary China, Yao first mentions the lively and large phonographic scene: armed with their mobile phones, many Chinese make short audio clips of everyday, noisy, chaotic, urban life. (Yao delicately remarks that this observation is in opposition to Western ideas and ideals of people like R. Murray Schaefer; the Chinese show little interest in sounds of the natural environment or the animal world.) Very popular is the social media app PaPa, where people upload their own sound recordings. According to Yao, PaPa has thus realized what Jacques Attali envisioned in the late 1970s: giving up an artist-oriented concept of art in favor of a stage where everyone creates their own music (p. 652). Additionally, professional sound artists in China are highly interested in cellphones, the Internet, and social media, which results in works based on unpredictable noises or online chatroom conversations and other net broadcasts, for example (p. 651).

People are gaining an aural consciousness. These audio platforms are indeed triggering an auditory discovery of the sonic self. (Dajuin Yao)

As for me, one of the most interesting essays in this book can be found in Section 4 on sound art and context: Brandon LaBelle’s “Sonic Site-Specificities.” Why? Because besides paying attention to several sound artworks in which physical as well as social or cultural environments are somehow incorporated, used, made audible, constructed, contested or questioned, LaBelle has been able to connect this to more general reflections on the value of sound art. For example, he states that “a sonic site-specificity is one that moves beyond the surface appearance of things, to listen into the architectures, the social experiences, the ecologies, and the often quiet or non-human soundings found therein […] relating to the unknown that lives beyond our experiences or habitats” (p. 520). According to LaBelle sound art thus invites us to “rehear the familiar,” which may lead to a new auditory consciousness, a “situation of care and consideration, of attunement and concentration” (p. 521) in which a play between “material reality and other-worldly sonic experience” (p. 522) can take place. I find this a very convincing and beautifully articulated argument in favor of sound art, site-specific or not. It responds – implicitly – to the often-heard argument, very well expressed in Seth Kim-Cohen’s In the Blink of an Ear, that sound studies all too often fall back into a strategy of thinking about the “sounds in themselves.” In this essay (and of course also in many of his other publications), LaBelle presents an ethical-political “justification” and “surplus value” for sound art.

Sound art, in other words, explicitly tunes us not only to all that resides here and there, but sets the conditions for great solidarity. (Brandon LaBelle)

The final contribution I like to mention here is Alexandra Supper’s essay on sonification, that is, on the difficult but interesting and challenging relation of sound art and science. Sonification, as Supper explains, should “complement existing, usually visual, data analysis techniques” by transforming data into sound in order to make it interesting and relevant (p. 492). Of course the tricky word here is “transforming,” as this means that a certain intervention is taking place, an intervention which is always already also a violation. (In this respect, one should of course also acknowledge that no data gathering is objective but is also realized through transformations, reductions, and other arbitrary decisions.) Supper makes clear that some practices that might be subsumed under the denominator sonification actually only translate data into sound for musical purposes (an example she mentions is Alvin Lucier’s “Music for Solo Performer”). Other sonification practices are designed primarily to communicate sometimes simplified messages to lay audiences. Supper’s interest goes to a third variant of sonification strategies, one which opens “new possibilities for thinking about scientific phenomena” (p. 494). The added value lies in uncovering alternative ways of thinking about scientific phenomena. Interesting examples listed by Supper are, among others, Andrea Polli’s “Sonic Antarctica,” Natasha Barrett’s “Aftershock,” and John Luther Adams “The Place Where You Go to Listen.”

The blurring of boundaries between art and science is quite typical for sonification. (Alexandra Supper)

Sound Art – Sound as a Medium of Art is a book that you can visit many times, from different angels, and with various objectives. It contains a wealth of historical and site-specific material, challenging reflections, and background information and gives an unprecedented overview both in text and images. The book stimulates the appetite to try to listen not only to these works (which is not always possible anyway, as they no longer exist or are locked away in the artists’ storage places), but to any new sound artworks or simply to our sonic environment. Good news is that this huge and rich book is already available for less than 55 US dollars.