Berio's Duetti per due Violini – an introduction

Joseph Puglia

History and intention of composition

Luciano Berio's 34 Duetti per due Violini were written in the period from 1979-1983. The pieces

stem from a conversation the composer had one evening with violinist and teacher Leonardo

Pinzauti, in which Pinzauti lamented that "other than those [duets] of Bartók, there are not enough

violin duets today."12 Berio proceeded to write 34 duets in the following four years, and although

these duets are clearly in Berio's own style and idiom, they are much indebted to Bartók's own set of

44 violin duets.

Much like Erich Doflein's request for Bartók to write "real music" aimed for young students3,

Berio's duets are short musical masterpieces also intended "for school violin teaching"4. Each duet

focuses on one or two musical and technical challenges, and serves to introduce 20th century

musical concepts to students. Some duets (e.g. #1, #12, #24) challenge the students by introducing

different manners of sound production to the student such as sul ponticello, sul tasto, aspro, or

"pppp quasi senza suono". Other duets (#26, #33) involve complicated left hand pizzicato

techniques. Still others (#2, #4) present rhythmic challenges of mixed meters in various

combinations of counting (e.g., 3/8+3/8+2/8, or 4/16+3/16, or 4/16+4/16+3/16).

Since each duet is very short, violinistic techniques are used as a basis for the musical motives of

the piece, the structural development of a duet, or modes of expression in a duet. This means that

finding musical expression in these techniques is in fact what gives character to the whole piece. In

duet #26 for example, the second violin combines the open [A] and [D] strings, with a left hand

pizzicato [A] and a drone [D] in the right hand. This serves as the basis for the accompaniment and

evokes the basic sound world of the duet. These sounds can be thought of to imitate a rosined wheel

and vibrating bridge of a hurdy-gurdy, or perhaps, a tin drum and fiddle. Finding the right sound

for this will make or break a performance of this duet. In duet #4, extreme rhythmic complexities

(4/16+4/16+3/16 and 4/16+3/16 in the first two bars) are actually heard by the listener as an

imitation of a folk-like manner of rubato. This gives the audience a very different experience than

the performer – while the performer is doing his or her best to count a very precise notation, the

audience instead hears an expressive rubato in a very simple melody.

1 Berio, Luciano. Duetti per due violini (author's note)

2 Universal Edition work introduction to Berio's Duetti per due violini

3 Vikarius

4 Berio, Luciano. Duetti per due violini (1979-1983), Preface

Theater

Central to any study of the Duetti is Berio's idea of theater in music. He speaks of his theatrical

ideal as bringing together opposite ideas, and having these opposites combine to make a third idea7.

For Berio, the ideal theatrical element in music consists of bringing together these opposites in

order to create a scene which had not existed before. In an interview with Rosanna Dalmonte, he

speaks directly of this, saying that:

"it is that of taking two simple and banal behaviors, such as 'walking in the rain' and

'typing' and putting them together in such a way that they transform and produce by

morphonogenesis a third behavior, which we don't understand because we have not seen it

before and because it is no longer only the combination of two banal behaviors8."

It is therefore imperative to a successful performance of these works that each voice sounds

individually, in its own character. Each line should have its own individual integrity, with the

combination of two lines creating a third expression, audible to the audience. Duet #24 is perhaps a

perfect example of this – Berio asks the second violin to play an accompaniment line "sempre molto

al ponticello", whereas the first violin plays a Sicilian folk song melody ordinario, but con sordino.

The combined effect of sul ponticello in the second violin and con sordino in the first violin

suggests to the audience the sound of an old scratchy record playing softly in the distance.

Throughout the entire duet cycle Berio frequently asks for the two players to play in completely

different manners from each other. He asks for differences in tone color, dynamics, articulation,

and tempo. In duet #1, the first violin begins sul tasto while the second violin begins sul ponticello.

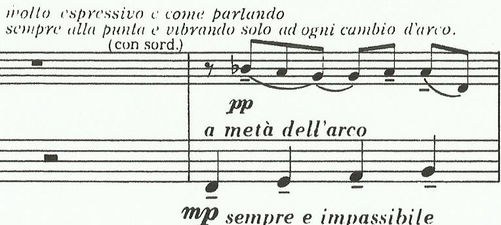

In duet #17, both violinists are given different dynamics for the majority of the piece - the second

violin is asked to play mp sempre e impassibile, while the first violin (playing a much more melodic

and ornamented line) is marked pp con sordino. Many duets call for a mute to be used by only one

player (e.g, #13, #17, #24). In duet #2, the second violin plays an accompaniment rhythm which

imitates a drum-like dance of [3/8+3/8+2/8], while the first violin plays a melody which phases

against that, sounding as a [2/8+2/8+3/8+3/8]. And in duets #22 and #27, the first and second violin

are given different metronome markings from each other. Even when writing in more traditional

manners in the Duetti, Berio still adheres to this principle of independence. In some cases, what

would naturally be considered to be the "accompaniment" line is instead marked by Berio to be

played much louder than the "melody".

This theatrical ideal is also one of the central ideas separating Berio's music from earlier classical

music which might be more familiar to young students. In music of Mozart, Schubert, or

Mendelsson, for example, prominent melodies are usually enhanced by accompaniment lines and

textures which exist to serve the melody. However in the Duetti, as in many other modern works, it is not always clear which line is melody and which is accompaniment. In duet #17, a D major scale

played by the second violin, although less melodically interesting and less expressively performed,

will by definition of the way it is written, be the more prominently heard voice. The independence,

individuality, and combination of voices is what gives expression to to the piece. This idea of

melodic and rhythmic independence is central to much 20th century music and can also be compared

to the loss of point perspective in 20th century painting. Whereas in earlier periods of art, the viewer

was asked to direct their focus towards one point on the canvas, with the loss of perspective the

viewer is instead invited to see the entire canvas as a field, to see any point as a possible central

focal point (as in cubism, for example), and can therefore find central points of expression and

meaning on any point of the canvas.

5 Berio, Luciano. Duetti per due violini (1979-1983)

6 Berio, Luciano. Duetti per due violini (1979-1983)

7 Berio, Luciano. Intervista sulla musica a cura di Rossana Dalmonte 158

8 Berio, Luciano. Intervista sulla musica a cura di Rossana Dalmonte 113

9 Berio, Luciano. Duetti per due violini (1979-1983)

Instructions for performance

Berio's original intention was to have his 34 duets be "volume 1" of a multi-volume

"kaleidoscope"10, with each set consisting of at least 20 duets, although he was not able to realize

this goal.11 He intended these pieces for study by young students and had specific ideas about their

performance, saying that

Some […] can be played by beginners, others […] by more advanced pupils, together with

their teachers […]. If the Duets are performed in front of an audience, it is preferable to

involve a large number of players of different age and proficiency. All the players (at least

24) will be seated on stage: Each pair will stand up only when it is its turn to play. There

should not be any pause between each duet. In a concert performance Duet 20

(EDOARDO) should be played last by all performers under a conductor.12

Duet #20 also contains seven brief solos in the first violin part, Berio asks that each of these solos is

played by a different performer.13

In my workshops and performances I have divided the difficulty of each duet part into easy,

intermediate, and difficult categories. In some cases both the 1st and the 2nd violin parts fall into the

same category (#28, for example, is "easy" for both players, whereas #33 is "difficult" for both). In

other duets one part is significantly more difficult than the other (#3 has a difficult 1st violin part and

an "intermediate" 2nd violin part, #17 has an "intermediate" 1st violin part and an "easy" 2nd violin

part). One can assume that the age of the performer should be related to the difficulty of the duet –

in other words, the "easy" duets should be played by young students on smaller violins, the

"intermediate" duets by more advanced students, and the "difficult" duets by teachers, professionals,

and the most advanced students. I have recorded and performed the duets in this manner and I have

found that there is indeed a musical logic to this approach.

However, Berio does not state the age or level a student needs to be in order to play specific duets.

This means that although many of the easiest duets do benefit in their expression from being

interpreted by young students playing on smaller violins, equally valid interpretations of these

"easy" duets can be given by older, more advanced players. One of the most interesting aspects of

these pieces is how different they can sound when played by different performers. In Duet #17, the

second violinist plays almost exclusively a one octave D major scale for the entire piece. It goes

without saying that this duet has an entirely different emotional effect if the second violinist is a

child playing on a small violin or a seasoned performer playing on a full-sized instrument. And the

pedagogical intentions of this duet remains regardless of age or level of performer – indeed, we

violinists continue to practice and search for improvements in our D major scales for our entire

lives!

Berio's compositional choices in these pieces and his instructions for their performance imply that

one of the central ideas behind a performance of the Duetti is a feeling of equality among all

players. Although some performers might be more experienced than others, each violinist

contributes a sound and interpretation which is unique in a performance of the entire duet cycle.

This variety and individuality of sound adds to the flow of dramatic tension in a complete

performance of the cycle. The sound created by a seven year old violinist playing on a 1/4 sized

violin is necessarily different from that of a professional with over 20 years of performing

experience playing on a full-sized instrument. Neither player is capable of imitating the other, and

any attempt to do so would sound contrived. The best that young and old players can do in these

works is to strive for the most convincing interpretation of which they are capable.

10 Berio, Luciano. Duetti per due violini (author's note)

11 Universal Edition work introduction to Berio's Duetti per due violini

12 Berio, Luciano. Duetti per due violini (1979-1983), Preface

13 Berio, Luciano. Duetti per due violini (1979-1983), Preface

Dedications

Each duet is named after a friend, colleague, or composer whom Berio admired. Of the dedications,

he states:

behind every duet there are personal reasons and situations: with BRUNO (Maderna), for

instance, there is the memory of “functional” music which we often composed together in

the fifties; MAJA (Pliseckaja) is the transformation of a Russian song, whereas ALDO

(Bennici) is a real Sicilian song; PIERRE (Boulez) was written for a farewell evening: it

develops from a small cell of his ...Explosante fixe...; GIORGIO FEDERICO (Ghedini) is in

memory of my years at the Conservatory in Milan. And so on... These Duetti are for me what

the vers de circonstance were for Mallarmé: that is, they are not necessarily based on deep

musical motivations, but rather connected by the fragile thread of daily occasions.14

Following, I have outlined some of my thoughts surrounding Berio's source materials for the

dedications to show how varied this "fragile thread of daily occasions" can be.

Duet #1 - BELA

An obvious place for the cycle to begin, since Berio almost certainly chose this dedication as

an homage to Bartók's 44 duets for two violins. Although I have found no direct quote of

Bartók's music in this duet, the opening rising and falling of a second (D E) in the second

violin is perhaps remeniscent of the rising second (E F) in Bartok's duet #10 (Ruthenian

song), Berio's use of the first violin's circling around the modes of [E] and [B] is remeniscent

of Bartók's same duet. And the bi-modality of Berio's duet is probably influenced by

Bartók's duet #11 (Cradle Song), a very important work in Bartók's set, since it is the first in

that set where both violins play in a different modality, and one of the few in which Bartók

asks the 1st and 2nd violin to play at different dynamic levels (mf and p, respectively).

Duet #6 - BRUNO

Berio says that this duet has "the memory of 'functional' music which we [Berio and Bruno

Maderna] often composed together in the fifties". Berio and Maderna often collaborated on

television and radio music in the 1950s in order to earn extra money, which by his own

account was always lacking at this point in his life. He speaks of this time in an interview

with Rossana Dalmonte in which he and Maderna were working together.

We started writing scores for whatever radio or television program, director, or

theater thought to have needed us. ...we collaborated on "functional" scores at an

astronomical speed. Bruno, already plump, seated at my Milanese table, occupied

himself with the strings and "fixed sounds" (which is what he called the guitar, piano,

celesta, and glockenspiel in the orchestra). I, on my feet at his back, occupied myself

with the wind instruments. We understood each other so well that it was enough to

give one glance at the other's pencil to instantly understand where he was going. We

were always late with our deadlines and I remember one astonished copyist

watching us finish a composition together in this way. He left with his mouth half

open, wide eyes, and blank stare: he resembled a caracature of Ghedini. What I

wanted to say is this: in these occasions of absolute musical cynicism, we always

found a way of searching for something, experimenting, and naturally, of learning

something.15

The functional music is not only represented in the traditional harmonies, phrasing, and

structure of this duet, but the memory of them writing at "astronomical speed" in which they

composed, the idea of them running back and forth to glance at the scores with which they

were busy, is reflected in the back and forth crescendi played by the two violins in the

opening of this duet.

Duet #10 – GIORGIO FEDERICO

In 1945 Berio enrolled at the conservatory in Milan, and three years later began studying

composition with Giorgio Federico Ghedini. Ghedini's style was very much in the neobaroque

tradition, and as a composition teacher he became one of the "major influences of

Berio's early career"16 This duet is said by Berio to be a memory of his conservatory days in

Milan. Ghedini's own neo-baroque influences are here reflected by the chorale-like structure

of this piece. The "baroque" inspiriation for the piece is perhaps even more accentuated by

the focus on the bass line which is marked to be played stronger than the melody line. One

can almost imagine Ghedini telling his students that the bass line is the basis and most

important line in all baroque music, and deserves a special attention.

Duet #17 - LEONARDO

The inspiration for this duet stems from Berio's conversation with Leonardo Pinzauti

lamenting the lack of good violin duets, other than those of Bartok1718. Pinzauti's work as a

violin teacher probably inspired Berio to make this one of the simplest duets for the second

violin (the student's part). Berio underlied this point by having the second violin part consist

almost entirely of a D major scale up and down from [D1] to [D2], five times. It was indeed

of this duet that Berio was speaking when he said:

Very often, as can be heard, one of the two parts is easier and focuses on specific

technical problems, on different expressive characters and even on violin stereotypes,

so that a young violinist can contribute, at times, even to a relatively complex

musical situation from a very simple angle – the playing of a D major scale, for

instance.19

Duet #24

The source material for this duet is Berio's favorite Sicilian song, "e si fussi pisci"20. Berio

himself made many arrangements of the song (including an arrangement for solo viola

which was given to Aldo Bennici, the dedicatee of this duet). Copies of the manuscript of

these arrangements are available at the website of the Centro Studi Luciano Berio online:

http://www.lucianoberio.org/node/1852

as well as:

http://www.lucianoberio.org/node/1854

In addition, a recording of Berio singing the folk song and accompanying himself at the

piano is also available on the Centro Studi website:

http://www.lucianoberio.org/node/1887

The text of the folk song is in a heavy Sicilian dialect:

E si fussi pisci

lu mari passassi

e si fussi aceddu

'nni tia vinissi

e vucca cu vucca

ti vurria vasari

e visu cu visu

parrari cu 'ttia.

This translates in English as:

If I were a fish

I would cross the sea

and if I were a bird

I would come to you

And mouth to mouth

I would like to kiss you

And face to face

I would like to talk to you.

Duet #28

Dedicated to Igor Stravinsky, the A minor tonality and main musical motive of this duet

(repetitions of the tones [D1], [E1]) are both derived from Stravinsky's Five Easy Pieces for

Piano Duet. They also share a strong resemblance to the "violin" motif from A Soldier's

Tale, which has a similar section also in A minor. The allusion to Stravinsky's Five Easy

Pieces is strengthened by the fact that this is one of the easiest duets in a technical sense, and

can therefore be played by some of the youngest students.

14 Berio, Luciano. Duetti per due violini (author's note)

15 Berio, Luciano. Intervista sulla musica a cura di Rossana Dalmonte 68-69

16 Osmond-Smith, David. Oxford Studies of Composers Berio 4

17 Berio, Luciano. Duetti per due violini (author's note)

18 Universal Edition work introduction to Berio's Duetti per due violini

19 Berio, Luciano. Duetti per due violini (author's note)

20 - from Centro Studi Luciano Berio: http://www.lucianoberio.org/node/1852

Pedagogical applications

Over the past few years I have led many masterclasses and workshops of these pieces with violinists

of all levels. This has given me the opportunity to see the effect these pieces have on students,

many of whom have had little to no prior opportunities to play 20th century music.

Whenever possible I have asked that even the youngest students already be far beyond the technical

level demanded by these pieces. This usually results in the student coming in to the first rehearsal

already having a firm command of the notes in the piece, and then being surprised that there is still

much work to be done. When this happens, students can use these pieces to push their own limits

as performers – to find sounds that are not necessarily beautiful but are still very expressive, to

extend their range of articulation, and to approach chamber music as an impromptu conversation

between equals, rather than an exercise in following a teacher.

Generally, students responded enthusiastically to the Duetti, even if they lacked prior experience

with 20th century music. The duets' firm link to the past, their historical, folk, and other influences

make them accessible to students. Because of this accessibility students are more able to absorb

strange techniques, complex meters, and dissonances more easily than they might with other

modern repertoire.

As a professional performing the Duetti with students, these workshops have also transformed my

own playing, performance skills, and musicianship. It has been my responsibility when performing

with children to find each student's individuality and add my voice to that, rather than to force them

into my own idea of what the piece should be. This is a subtle but important shift from one's

normal approach of striving towards a perfect and ideal interpretation in one's inner ear. When

playing with students or amateur violinists, our normal ideal of a perfect performance is not valid in

the same way. What is possible, however, is finding an individual voice and communicating that

voice to the audience. I have since applied this way of thinking to my other chamber music

performances, which has helped me enormously.

What I also discovered, which surprised me at first, is that the individual personalities of players are

most audible when players are at the highest and lowest levels. Both the most seasoned

professionals and the youngest students tend to play with recognizeable and individual sounds, and

have more variety of approaches than intermediate level violinists. With the oldest and most

experienced players the reasons for this are obvious: experienced players have had the most time to

find their own voice on the violin and develop their own musical personalities. The youngest

students, on the other hand, have had the least time to work beyond personal habits of playing and

holding the instrument that they quickly develop in the first years. Because of this, their own

personalities shine through all the more. A young violinist who has not yet mastered a truly legato

bow change will have his or her own very recognizeable and unique articulation. A student who is

still developing the basics of vibrato and who can only vibrate at one speed and one width will also

have a very specific and individual color present in their sound. The next step in these youngsters'

musical education will be to learn the tools that every violinist must have in his or her repertoire:

mastering not only the basics of sound production, but also developing a wide variety of colors,

articulations, and dynamics. It is only after students learn these tools that they can reach the final

goal: to decide at will which tool to use, and perhaps most importantly, when to break the "rules"

they have learned from their teachers.

Conclusion

Berio intended that the Duetti introduce concepts of 20th century music to violin students. However,

I have found that the Duetti also serve as a great introduction to 20th century music for

inexperienced concertgoers. The pieces are very accessible, and for many different reasons. Berio's

friend Lele D'amico once described him as a musical "omnivore"21, and his interest in all types of

music – jazz, folk, dodecaphonic, baroque, electronic, and more – is audible in these duets. The

short length of each piece assures that even audience members with the shortest attention spans can

listen to an entire work without losing their concentration. Since each duet uses a different

combination of 20th century compositional techniques, audiences are given many different examples

of what kinds of sounds are common in 20th century music. Because of these quick changes in

style, monotony is never an issue. Many of the Duetti still use tonal or modal harmonies (#10 is

triadic and written as a chorale in three voices, #17 drifts between g minor and D major , #24 and

#26 are in D major, #28 in a minor). Familiar harmonies therefore allow audiences to absorb new

concepts and sounds while still listening to chords they understand. And there are theatrical

elements of a live performance which add visual and auditory excitement for the audience member.

Since a different combination of violinists perform almost every duet, audience members are given

an opportunity to hear and compare each performer's individual qualities. Audiences therefore learn

not only about what kinds of variety exist in composition, but also about what kinds of variety exist

in interpretation. And since violinists of all ages and abilities are asked to collaborate as equal

partners on stage, audience members are asked to value each performer's individuality and efforts as

people and musicians, and not only on their technical skill as instrumentalists.

These ideas of equality and collaboration are perhaps best supported by a quote from Berio's

Remarks to the Kind Lady of Baltimore, a speech where he struggles to give an answer to a question

that had once been posed to him after a lecture: "Mr. Berio, how do you relate your work to life?"

He attempts many replies to this quetion, and by his own account, none of his answers fully capture

the relations behind his music and life. However, his ideas imply a spirit of discovery and humanity

which lie at the heart of these duets. In one of his many attempts at an answer, he states

I was only able to answer that I didn't know precisely...I said that in any case a complex

tissue of relations exists and that whatever we do – not necessarily music – is an attempt to

uncover a part of it and to become more aware of what we are and where we are.22

21 Berio, Luciano. Intervista sulla musica a cura di Rossana Dalmonte 110

22 Berio, Luciano. Remarks to the Kind Lady of Baltimore

Bibliography

Berio, Luciano. Duetti per due violini (1979-1983), Preface (UE 17757, Universal Edition, Wien,

1982)

Berio, Luciano. Duetti per due violini (author's note). Retrieved 20/12/2017 from

http://www.lucianoberio.org/node/1371?237685848=1

Berio, Luciano. Intervista sulla musica a cura di Rossana Dalmonte (Gius, Laterza & Figli, Bari

1981)

Berio, Luciano. Remarks to the Kind Lady of Baltimore. Retrieved 29/1/2018 from

http://www.lucianoberio.org/node/35905?1574735542=1

Centro Studi Luciano Berio. Luciano Berio, E si fussi pisci. Retrieved 29/1/2018 from

http://www.lucianoberio.org/node/1852

Osmond-Smith, David. Oxford Studies of Composers Berio (Oxford University Press, New York,

1991)

Universal Edition work introduction to Berio's Duetti per due violini retrieved 29/1/2018 from

https://www.universaledition.com/composers-and-works/luciano-berio-54/works/duetti-per-dueviolini-

2177.

Vikárius, László. Translated by Richard Robinson. CD liner notes to Bartók: Sonata for Solo Violin

- 44 Duos, Barnabas Kelemen & Katalin Kokas, BMC Records 2006