Project One examined the effects of external focus on trumpeters’ skill acquisition, and Project Two extended the investigation to the performance experience of the same seven participants. Using external focus in an artistic context was taken one step further in Project Three, where instead of only trumpeters (with timpani and basso continuo players), a mixed ensemble including string players, trumpeters and keyboard players prepared and performed together using the previously described Audtion Practice Tool (APT) as well as a performance preparation approach based on the concept of external focus.

The researcher (who acted also as coach for the project) and a guest coach – violinist Rachael Beesley – coached the ensemble using an approach based on external focus. The overarching concept for the project was that music is a language and not a technical exercise. The main components/characteristics of the coaching approach were: using APT, avoiding technical language (e.g. referring to tempo, rhythm, intonation, articulation, pointing out wrong notes), using metaphors, addressing what the music or phrase is "saying": i.e. focussing on expression and communication.

The project was called “Biber Immersion Project” as the intention was that the participants would be immersed on many levels in music-making. In addition to rehearsing the repertoire (sonatas by H.I.F. Biber), the project consisted of extra components designed to enhance the idea of external focus. Added elements that made Project Three different from the previous project were: movement sessions, improvisation sessions, and lectures that provided the participants with information on the topics of "music as a language" and baroque rhetoric and “affect”. A rationale for each of these elements follows.

Rationale for Each of the Added Elements

One major difference between this project and the previous two is that external focus was explained to the participants (in the opening lecture) in the context of playing baroque music in a rhetorical way. In order to help the participants feel at home in their body, movement sessions were included in the project. Each day a movement specialist led the participants for an hour of body awareness and movement exercises. The expectation was that this could help the participants to feel comfortable with using their body to express themselves through gesturing.

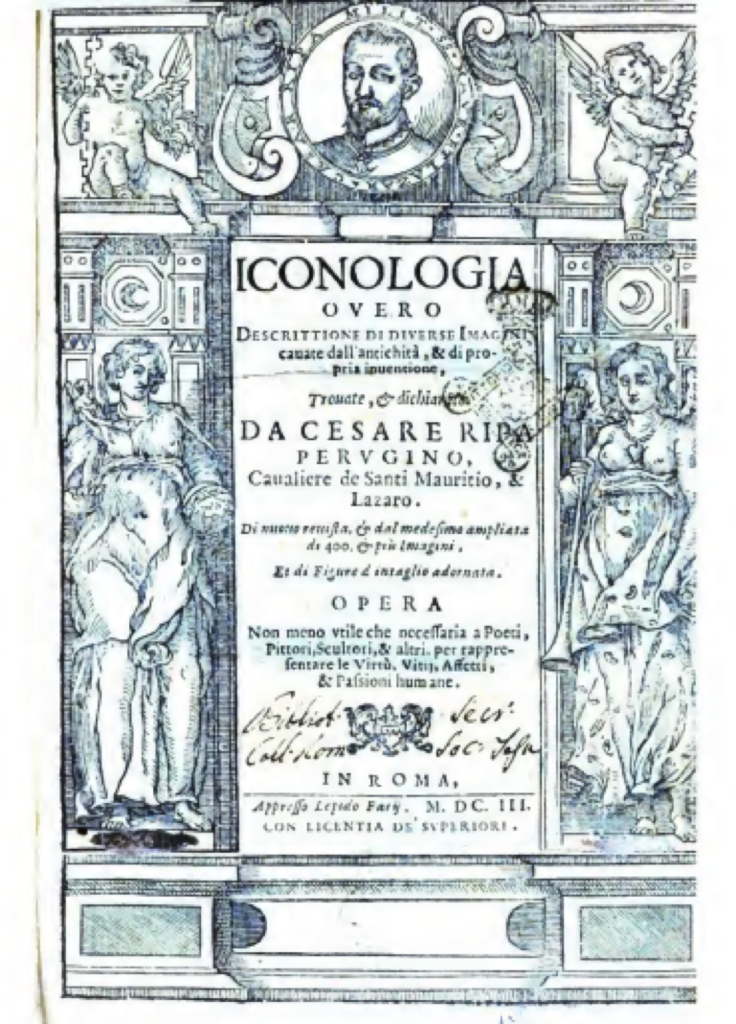

Improvisation sessions were introduced in order to help the participants feel freer in their ability to express themselves and explore the music. A lecture on rhetoric was presented in order to provide some insight into how to approach performing the repertoire (and baroque music in general) by focussing on emotions and "affect" (i.e. distal external focus). The lecturer used iconographical allegories from the Renaissance and Baroque eras to illustrate how “affect” and emotion were explained in a non-verbal way.

The research questions for Project Three were the same as to those for Project Two except that they referred to an ensemble of mixed instruments rather than only trumpeters. The additional research questions for Project Three were: [RQ 6] How did preparing a project using external focus affect the participants’ (mixed ensemble) learning and performance experience? [RQ 7] Can previously found effects of APT on trumpet players be replicated in a more diverse group of musicians? The hypothesis was that Project Three would result in higher than usual levels of engagement with the music and with the ensemble for the participants and that they would be inspired to use and develop an external focus approach in some way in their future practice.

The musicians were recruited by advertising at the Royal Conservatoire, The Hague (see Figure 7.1). They were asked to be available for the entire week, for an "Immersion Project" and to attend all sessions. The project began on Sunday 3rd April and ended with a concert on Thursday 7th April 2016, and included lectures, rehearsals, movement sessions and improvisation sessions.

Day one began with the lecture “Music as a Language” by the researcher and followed with (ensemble) rehearsals, a movement session and another rehearsal. Day two contained rehearsals and a movement session as well as a lecture on rhetoric and an improvisation session. Days three and four contained rehearsals, improvisation sessions and movement sessions. The final day consisted of a general rehearsal, a movement session and the concert (see Appendix V for the full schedule). After the concert, each participant was handed the questionnaire and asked to fill it out during the next days.

Method

Participants

The 17 participants (11 females, 6 males) were all students of the early music department of the Royal Conservatoire, The Hague, and consisted of five trumpeters (three of whom participated in projects one and two, one additional player as well as the researcher herself), five violin players (plus coach Rachael Beesley), four viola da gamba players, a violone player, a lute player, an organist and a harpsichord player.

Apparatus, Materials and Measures

Variables for Project Three

Project Three had a similar aim to Project Two – to find out how basing the preparation of an artistic project for musicians affected the participants. The dependent variables were the same as Project Two: motivation, confidence, ability to play accurately and musically, nervousness, enjoyment, engagement, and focus during performance (see Figure 4.1).

Questionnaire

A questionnaire was handed out after the concert and all participants were invited to fill it out and send it back to the researcher. The questionnaire (see Appendix R) consisted of questions about how they experienced the project and what they learned. The first three questions were open questions in order to see whether the participants responded to the elements of the project connected to external focus without being prompted. The participants were free to give honest impressions of their experience. The questions included: What was striking/touching/memorable about this project? What did I notice, and how was this project different from other KC projects? What did I learn & what will I take with me after the project? After the concert: How did I experience this concert and how did this experience differ from other chamber music concerts I have played in recently?

Question 4: Do you have suggestions that may help a project like this to work more effectively? Please write them here – was a check on the design of the project.

Recordings

Parts of the group rehearsals and the whole concert were video recorded by filmmaker Daniel Brüggen, using professional filming equipment (as in Project Two, these recordings were made for documentation purposes rather than answering the current research question).

APT

The Audiation Practice Tool (previously described in Chapter 4, and see Appendix H) was used in the rehearsals.

Repertoire

The program consisted of nine sonatas from Sonatae tam aris quam aulis servientes by Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber, and six duets by the same composer. Music by Biber was chosen because it is both attractive and challenging for all members of the ensemble. Biber’s writing for violin is often virtuosic and his trumpet parts are considered by many to be more musical and lyrical than most literature for baroque trumpet. See Appendix U for the complete program.

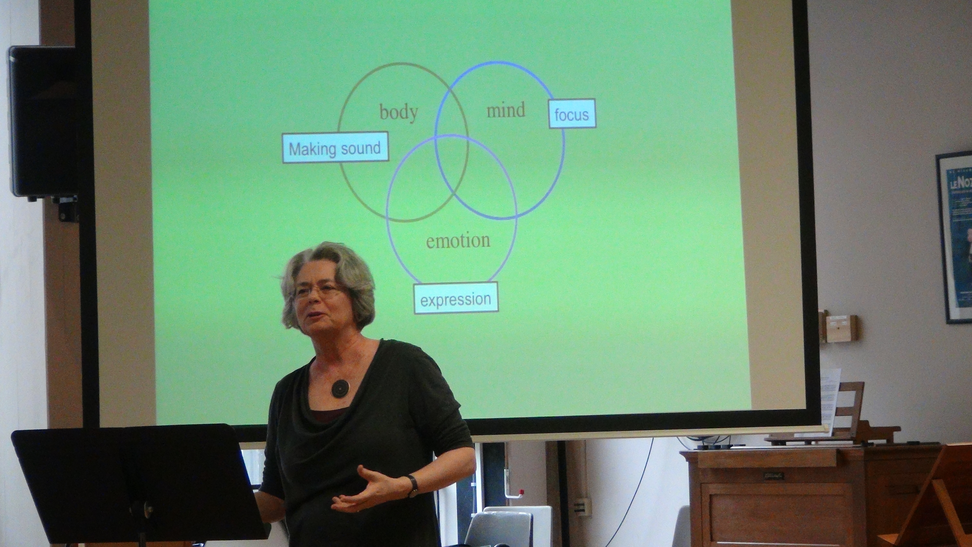

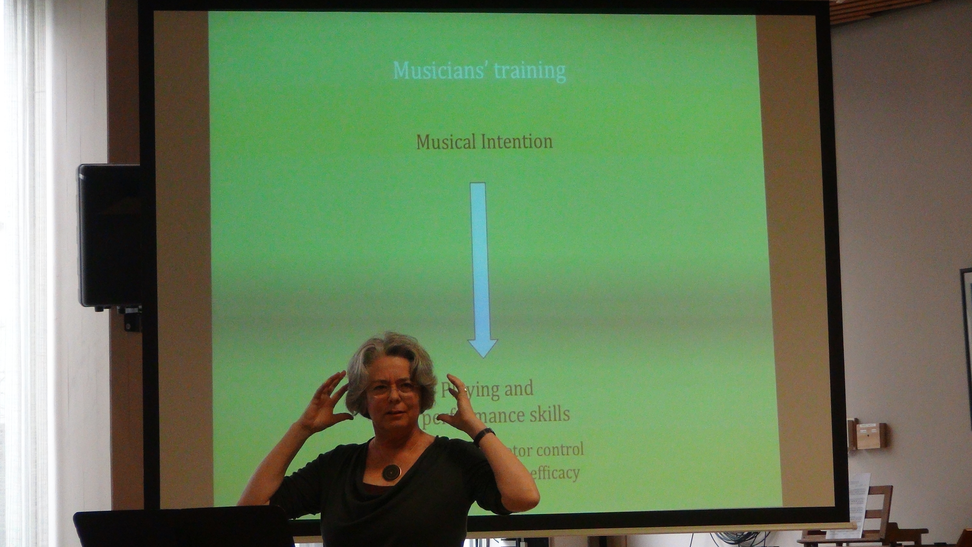

Lecture "Music as a Language"

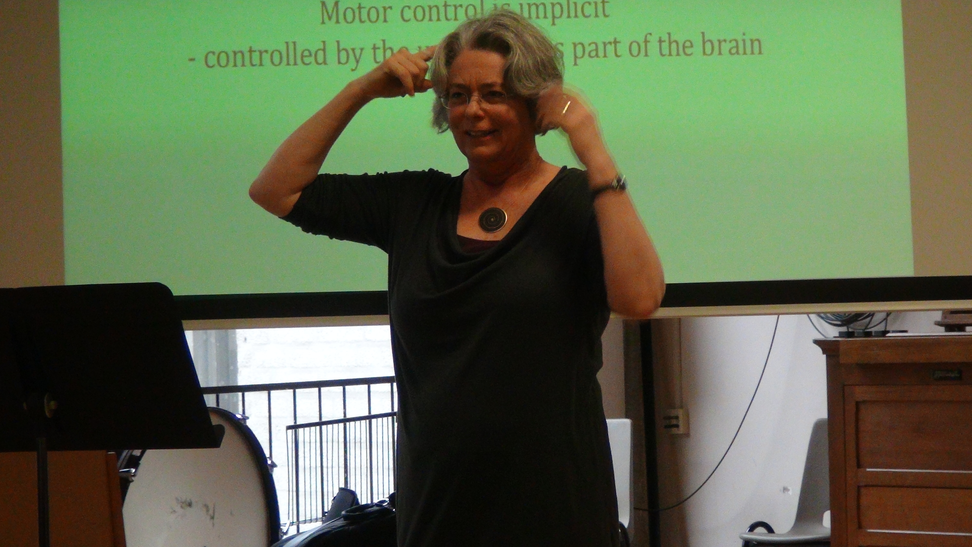

The researcher opened the project with a lecture that explained that rather than approaching music in a technical way, we as musicians could benefit from approaching it as a language. Focus and exploration of the repertoire could be on what the music is portraying – the emotions embedded within it; that music is a form of rhetoric and that the role of the musician is to move the listener. Participants were told that during the project we would avoid technical language and internal focus and rather find ways to learn, rehearse and perform by using external focus; that the emphasis would be on the what (the intended effect) rather than on the how (internal focus and technical and analytical thinking). The structure for the week was also explained at the end of the lecture.

Movement Sessions

The movement sessions included grounding, movement and bodywork exercises developed by the teacher Fajo Jansen.

Improvisation Sessions

Improvisation exercises were designed by harpsichord student Valentina Villaseñor, and involved both melodic and harmonic aspects of improvisation loosely connected with performance of baroque music.

Lecture on Rhetoric

A lecture about baroque rhetoric and the "affects" examined the conveying of affect in musical performance, and was illustrated using examples from iconographical collections of allegories, vices, virtues, passions and affects by Cesare Ripa.

Data Analysis

Data were gathered from the questionnaire, and the answers to the first three questions were analysed in the same way as the qualitative material from the other two projects – by using a global coding method and identifying the themes that emerged (for full transcripts of the answers, see Appendix S). Answers to question 4 (regarding suggestions for improving the project) were used as a check if there were any weaknesses in the design of the project.

|

THEMES |

Total participants

|

|

1. External focus |

|

|

Evidence of external focus/audiation/moving the listener |

6 |

|

More clarity/awareness of the musical goals & meaning |

4 |

|

2. Experience of/effect on the player |

|

|

Positive experience/enjoyment |

8 |

|

Holistic/body mind connection/in the moment/in flow |

6 |

|

More connection (music/ensemble/audience) |

6 |

|

3. Effective practice/rehearsal methods |

|

|

APT/gesture |

4 |

|

Movement |

5 |

|

Improvisation |

2 |

|

Information on ‘affects’ |

3 |

|

Better ensemble playing |

3 |

|

Coaching method |

6 |

|

4. Insights & change |

|

|

New understanding |

6 |

|

Ideas for new strategies/approaches |

4 |

|

Intention to use and develop the external focus approach in the future |

3 |

The themes that emerged from the post-project questionnaire were grouped into four categories:

1. All but one of the (eight) respondents mentioned experiencing some form of external focus, and for some, external focus was the main issue: e.g. “The difference with other concerts is that, for the first time, I was focussed on connecting with people, ensemble and audience, rather than creating something or thinking about technical things. I really felt music as a communication tool, as a language”.

2. The project was a positive experience for all who answered the questionnaire – the key word being “connection” – with the other musicians, with the music and with the audience. Many players reported a “flow experience” of total engagement during the concert.

3. Most of the respondents mentioned the effectiveness of the way the project was coached. Specific elements that struck the players as being important were the movement sessions and the use of APT (in particular gesture and singing).

4. The project inspired new understanding as well as ideas for how to approach practice and performance preparation.

The answers to question 4 (suggestions for improving the project) included that the project could be extended, and some comments about improving scheduling. Paradoxically, the participant who only came to the rehearsal sessions suggested to the coaches that the other sessions and practicing with APT need not be compulsory, whereas two of the participants who did all of the sessions, found it disturbing that not everyone was fully committed to the whole experience. The invitation to join the project stipulated that everyone had to attend every session, but this did not happen, because of busy schedules and some reluctance from one or two of the participants (see above comment). Approximately two thirds of the group attended the movement sessions, and one half attended the improvisation sessions. All participants were present for the rehearsals and for the two lectures.

Results

Eight of the 17 participants filled out the post-project questionnaire.

The results of the questionnaire are displayed in Table 7.1 (to view the questionnaire, see Appendix R, for full transcripts see Appendix S).

The video "Practicing Musical Intention" shows how the group practiced a segment of music using APT. The final rendition of the musical segment is from the concert – one day after the rehearsal shown at the beginning of the video (with no rehearsal in between the concert version acts as a "retention test").

Discussion

The third and final project of this study was an opportunity to expose all types of instrumentalists (string players, keyboard players, as well as brass players) to an approach to learning repertoire and performance using external focus.

Effects on Learning

Ten sonatas constituted a lot of repertoire to be prepared in this short time, and yet by the concert the musicians felt that they could focus on musicality and communication. Some noticed the absence of a technical approach but no one reported missing it. Most of the respondents indicated that they gained new knowledge or insights on learning, which they would take away with them.

Effects on Performance Experience

The project was designed to focus on musical intention during the rehearsals and also during the performance. Six of the eight respondents referred to a ‘flow’ state: e.g. “I felt very present in each moment in this concert, and it did also seem to go by very quickly”. Anecdotally, it appeared that the response from the audience was very enthusiastic, and the attendance and atmosphere at the post-concert drinks at a nearby bar confirmed that there was overwhelming enthusiasm from the players. Everyone was there (this is unusual for school projects) and even the players who had been most sceptical during the project stated that it was one of their best performances (observation by the violin coach after speaking to the players after the performance).

Limitations, Problems and Potential Biases for Project Three

All participants were asked to attend all of the sessions, as it was important that the project was an experience of immersion. Due to students’ busy schedules and/or reluctance to be out of their comfort zone, some did not attend every movement or improvisation session (one third was not present at the movement sessions on days two and three, and one half did not attend the improvisation sessions). The project would have benefitted from being outside of the participants’ daily life and schedule, to provide a more immersive quality.

Only around half of the participants (eight out of 17) filled out and handed in the questionnaire. This means that the feedback from participants is not complete. This is unfortunate, as a full response would have given a more balanced picture. Another limitation was the lack of a control condition.

Broader Relevance of the Findings

It was noteworthy that the participants had a positive response to the project, and also that they found it very different to what they normally experienced at the conservatoire. There were several positive aspects that stood out for participants, including the use of external focus, movement sessions and improvisation sessions. In addition, the fact that the two coaches played and performed together with the students and that there was no conductor seemed to enhance the experience – providing modelling (from the coaches) but also encouraging autonomy in the student musicians. The main aim of Projects Two and Three was to extend the inquiry into the effects of external focus – firstly to an ensemble concert preparation and performance setting, and secondly to a wider variety of instruments. The findings from Projects Two and Three should of course be extended to larger groups, but in their current form suggest that conservatoires could benefit from integrating external focus instruction and methods into group rehearsals, and also from creating holistic learning environments.

References for PART II: Chapters 4–7

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Duke, R., Cash, C. & Allen, S. (2011). Focus of attention affects performance of motor skills in music. Journal of Research in Music Education, 59(1), 44–55.

Dweck, C. (2000). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development (Essays in social psychology). Philadelphia: Psychology Press.

Dweck, C. (2008). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books.

Frick, U. (2011). An Introduction to qualitative research. London: Sage.

Gordon, E. (2001). Preparatory audiation, audiation, and music learning theory. Chicago, USA: GIA Publications.

Guss-West, C., & Wulf, G. (2016). Attentional focus in classical ballet: A survey of professional dancers. Journal of Dance Medicine and Science, 20, 23–29.

Keller, P. (2012). Mental imagery in music performance: underlying mechanisms and potential benefits. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. ISSN 0077-8923.

Pascua, L., Wulf, G., & Lewethwaite, R. (2015). Additive benefits of external focus and enhanced performance expectancy for motor learning. Journal of Sports Sciences, 33(1), 58–66.

Ripa, C. (1603). Overo Descrittione Di Diverse Imagini cauate dall’antichità, & di Propria inuentione. Rome.

Ritchie, L. & Williamon, A. (2010). Measuring distinct types of musical self-efficacy. Psychology of Music, 39(3), 328–344.

Schmidt, R., & Lee, T. (2012). Principles of practice for learning motor skills: Some implications for practice and instruction in music. In A. Mornell (Ed.), Art in Motion II (pp. 17–51). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Trusheim, W. (1991). Audiation and mental imagery: Implications for Artistic Performance. The Quarterly, 2(1–2), 138–147.

Wulf, G. (2013). Attentional focus and motor learning: a review of 15 years. International review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(1), 77–104.

Wulf, G., & Lewthwaite, R. (2016). Optimizing performance through intrinsic motivation and attention for learning: The OPTIMAL theory of motor learning. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review.