Breaching Sonic Barriers? Sound Studies as a Transdiscipline

Vincent Meelberg, Marcel Cobussen, Sharon Stewart, Jan Nieuwenhuis

Introduction

How does snow sound? Crunching and crackling when it is thick and fresh; squelchy and splashy when it is sleet; tapping soft and muffled as heavy flakes fall on trees and bushes.

According to Bernie Krause snow creates a distinct acoustic environment, one that is as capricious in range as are the conditions under which snow occurs (Krause 2012, 47). Just as the acoustic characteristics of snow are heterogeneous and variable, so are its semantics and the psychoacoustic level on which its sounds can be described. When we woke up on the morning of December 7, 2012, we were not very happy with the view of an immaculately white urban landscape nor with its accompanying specific, dampened, snowy silence. On that date we, the editors of the Journal of Sonic Studies (JSS), were supposed to host some 25 Dutch sound experts in the center for contemporary art in Leiden, Scheltema, and snow would imply that some of them would not be able to make it to Leiden due to train cancellations.

The Expert Meeting

Why this Dutch expert meeting on sound? First of all, more and more literature and research shows that humankind has always experienced an auditory engagement with the world; however, as yet this has attracted (too) little attention. Secondly, to study sound is not something obvious in The Netherlands. Even though much research on sound and sonic culture is taking place, this research is rather fragmented and scattered around different university departments, independent research institutes, artistic studios, and policy bureaus. Besides, it most often takes place in the peripheries of already-established disciplines and institutions. In light of the above, finding sound experts both inside and outside of the academic world had already turned out to be a real quest. However, after a rather difficult start, the list of sound experts based in The Netherlands became longer and longer. Of course, and this is the third point, the editors of JSS, tried and tested in music, philosophy, and cultural studies, were well-informed about research activities regarding sound in those fields; however, and this explains the difficult start, insight about similar activities in, for example, the hard sciences and governmental organizations was lacking. And that was exactly one of the main aims of this expert meeting: to assemble a group of researchers and artists, a group of experts of various disciplines and backgrounds, to exchange ideas, knowledge, interests, and fascination about our auditory environment, to bring together different voices and perspectives related to sound, to create an opportunity to meet and exchange interests and knowledge. In other words, according to the JSS editors, sound studies can benefit greatly from many different approaches; sound studies should be truly inter-, multi- or trans-disciplinary.

Context

Our auditory environment (and with “our” we mean both humans and animals) can be studied through many different approaches, leading to many different theories that are operative in many different discourses and disciplines. The approach, theory, and discourse that we choose will, to a large extent, determine what we choose to perceive and how and why we listen. In other words, our ears do not seem to be neutral transmitters. Influenced by our scientific predeterminations, disciplinary or institutional boundaries, and personal interests, they let us hear what we want to be audible – a scholarly cocktail party phenomenon, that is, being able to focus one’s auditory attention on a particular stimulus while filtering out a range of others.

So, what happened when these experts, somehow representing all those different approaches, theories, and discourses met on December 7, 2012 in Scheltema, Leiden, despite the weather conditions? Did it lead to a Babel-like confusion? To mutual incomprehension and a lack of interest? Or to fruitful discussions, to shattering prejudices and ignorance, to new insights, motivations, and topics? Of course the editors were hoping that institutional, scholarly and theoretical boundaries could be transgressed, that new collaborations and networks could occur; they were hoping for a biologist who could teach a sound artist while learning from an architect, and for a sound designer who could teach a philosopher while learning from a cognitive scientist. And vice versa of course.

This multimedia report should give an impression of the encounters that took place, encounters between people from various disciplines, encounters between various research interests, encounters between various discourses and inputs.

First Observations

The expert meeting led to some interesting discussions that showed how notions, considered self-evident in one discipline, were questionable and problematic in other disciplines. Concepts such as memory, meaning, affect, and emotion appear to be ascribed different meanings within different disciplines. Of course, it was impossible to arrive at some kind of consensus about these issues during this one-day meeting, but the mere realization, and, to an extent, the acceptance that these concepts carry different meanings and values for researchers, artists, and policy makers, was in itself already very productive.

Convergence toward, or arrival at, some kind of interdisciplinary approach to sound did not occur. And perhaps one should not strive for that, either. The main aim of the meeting was not so much to bridge the gaps but to respect the differences, to notice them, to make them productive instead of simply ignoring scholars and discourses from non-familiar disciplines. What happened was that the study of sound was implicitly regarded as a transdiscipline: a field in which attempts were made to understand, and critique, each other’s discipline through the lens of an other discipline. Thus, instead of using concepts and methods from, say, physics to be used in philosophical research – which would be an interdisciplinary approach – philosophical issues were questioned from a scientific point of view, and vice versa. Through respectfully breaching disciplinary boundaries, a productive kind of misunderstanding emerged, one that might lead to new questions related to sonic phenomena.

“What is the meaning and significance of sound for living beings and their environment?” “Which position does sound take in your discipline or in your specific research? Is sound the object of your research? A methodological instrument? Is sound the outcome of your work or, conversely, the point of departure?” “What are the key concepts in your discipline or research?” “And what can someone from outside your discipline learn from your research?”

Those were some of the initial questions which directed the presentations of all participants. And these presentations revealed that all these different forms of sound studies might be seen (or heard) as addressing two, interrelated, themes: how sound is experienced and the relation between sound and space.

This will be apparent in the subjective – or rather: transdisciplinary – impression of the meeting below, in which we do not give a chronological overview of the day. Instead, we seek to show how the different presentations address these themes, viewed through our own disciplinary lenses: critical theory, continental philosophy, music.

Experiencing Sound

An awareness of sound starts with hearing or, in other words, aural perception, and perception involves physical, biological, psychological, and cultural phenomena. Thus, if one intends to study, either quantitatively or qualitatively, sonic experience, one needs to be aware of the multifacetedness of perception. Dik Hermes argued that the study of perception of reality amounts to finding relations between “three worlds” as he calls it: the abstract world of the laws of physics, the world as we can measure by physical equipment, and the world of perception. The first two worlds can be studied without human observers as participants, but studying the perceived world requires perceptual experiments with human observers. Hermes states that in the process of auditory perception, the perceptual attributes of the perceived events do not have a direct relation with the acoustic events as we measure them. The phenomenon of virtual pitch illustrates this.

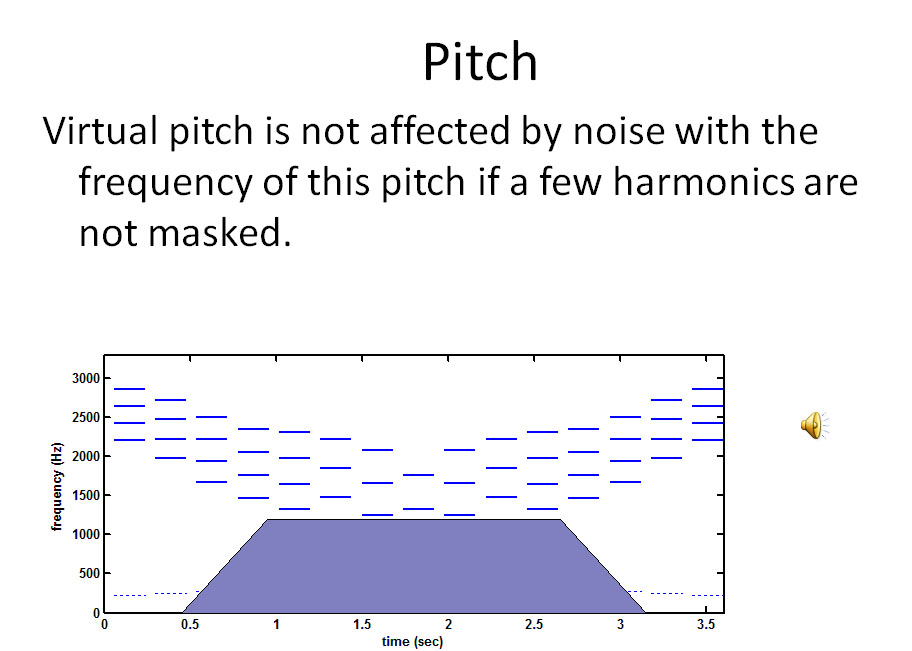

Demonstration of a melody, do re mi fa sol la si do si la sol fa mi re do, composed of virtual pitches. The melody is represented by the dashed lines, and, except for the middle note, consists of virtual pitches. So, this melody is neither physically present nor measurable. The physically present frequency components, represented by the continuous lines, are not heard as separate tones. (Adapted from Reinier Plomp, Hoe wij horen: over de toon die de muziek maakt. Breukelen, 1998.)

Certain combinations of measurable – in this case harmonic – frequency components can generate the perception of tones with pitches that are physically absent. Hence, they cannot be registered by measuring instruments, but are nevertheless perceived - that is constructed – by the listener’s hearing system as the pitches of these tones, while the frequencies of the physically present components are not perceived.

Hermes also addressed the notion of direct perception. According to ecological psychology, perception is direct, i.e., unmediated by inference or memory. Ecological psychology states that the recognition of a bird song, for instance, is achieved without engaging memory, through a process of “atunement”, just as a radio has no memory for a certain broadcasting frequency but is tuned to it and, after being switched on, immediately starts receiving.

This account of perception met with considerable resistance, especially from researchers in the humanities, bringing to forefront their premise that perception and recognition detached from memory is impossible. Perhaps the concept of “atunement” implies a certain kind of memory as well; however, during the discussion following Hermes’ presentation this did not become clear.

What was generally acknowledged, though, was that sound and mood are strongly related. Tjeerd Andringa explained how sounds influence our experience of environments. By defining emotion as action readiness, Andringa suggested that, because sounds are able to evoke emotions, they elicit expectations and strategies. Especially important is a feeling of safety. Without audible indications of safety, one must be on constant alert, which makes it difficult to concentrate on, for example, a book, because all sounds that stand out attract attention away from the book. In contrast, an abundance of sounds associated with a safe situation makes it easy to relax, play, or concentrate. Sounds that now stand out contribute to the overall atmosphere without attracting too much attention or disturbing activities.

Anne Bolders also discussed the relation between sound and emotion, from a converse point of view. She is interested in the influence of emotion on listening. Bolders claims that emotional states codetermine the way human subjects focus their hearing. According to her research, emotions influence the manner in which human subjects process sound. As an example she discussed how test participants who were brought in a happy or a sad mood interpreted ambiguous melodic lines as either rising or falling, depending on their emotional mental states.[1] This experiment demonstrated that sad participants judged the lines more often as falling than happy ones. While this might not be entirely self-evident (at least not to critical theorists), previous research showed that rising tone sequences are rated as more “happy” than falling sequences (Collier and Hubbard, 2001).[2] The challenges of getting a test participant in a happy or sad mental state and correctly measuring this state raised some questions with several researchers. Emotional associations and/or responses that rising and falling musical melodies might or might not elicit, are forms of musical meaning attribution, a phenomenon that was also addressed by Dirk Moelants. He argued that musical communication is impossible, in the sense that listeners cannot identify the musical intentions of the performer. Listeners do regard music as being expressive, but a performer can never be certain that the message s/he wants to communicate through her/his music will be understood by listeners.[3]

This has nothing to do with listeners suffering from some kind of hearing impairment. Rather, the ambiguity of music prevents any unambiguous transmission of messages through music. Moreover, as Jan de Laat explained, hearing impairment is an affliction that is far more common with (professional) musicians than with listeners who are not musicians themselves. Only because musicians are “better” listeners, are they able to remain capable of performing music or understanding speech in a noisy environment. In quantitative terms, their hearing might be worse than non-musicians, but in qualitative terms it might not be. This is corroborated by research done at Northwestern University, which showed that lifelong musical training appears to confer advantages in at least two important functions known to decline with age: memory and the ability to hear speech in noise. Consequently, despite the fact that musicians are exposed to high sound levels more than average listeners are, their ability to listen remains intact.

Sound and Space

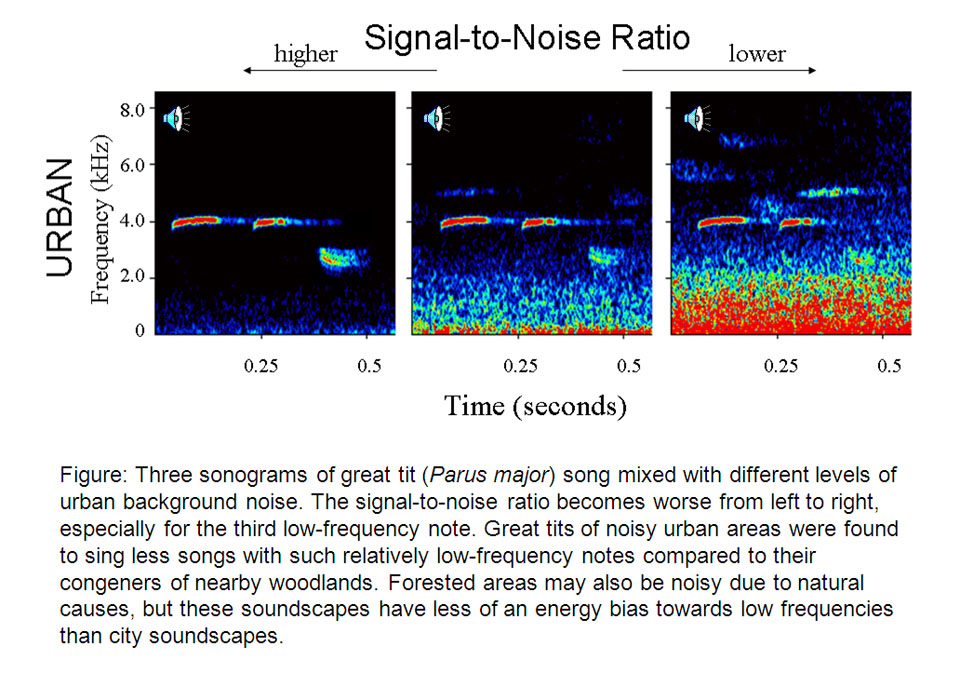

Of course, human beings are not the only form of life on this planet that attentively listens to its environment and engages in complex forms of acoustic communication. Hans Slabbekoorn explained that certain animals are capable of adapting their acoustic communication to their sonic environment. Urbanization, in particular, has had a profound effect on the way animals, which live in or near urban environments, communicate. Urban acoustic ecologies are characterized by sounds that mask a certain band of frequencies, thus drowning out sounds that certain animals make to communicate. Slabbekoorn showed that the songs of the same species of birds may differ, depending on whether they live near or in cities, or in rural areas.

“Urbanized” animals, such as these birds, seem to adapt their acoustic communication to the urban sonic environment they inhabit. These acoustic adjustments could take place at different time scales: immediately in response to fluctuations in noise level, during ontogeny within the life of an individual animal, across multiple generations through evolutionary adaptation, or a combination of these.[4]

This example shows how strong and important the relation is between sound and space. Space codetermines the kinds of sounds we can make, just as space may have its own characteristic set of sounds. Justin Bennett is a sound artist who attempts to grasp these sets of sounds. He does so not merely through recording them, but by using compositional techniques to reveal certain aspects of sonic environments that would otherwise remain hidden from or unattended by the human ear. He explained that he applies rhythmic and other temporal alterations in order to make these aspects audible – and sometimes visual as well, in the form of two-dimensional interpretations of sound analysis – to the human listener. Moreover, he considers field recording and manipulation as a trace of someone’s, namely the sound artist’s, active listening. Through the sound artist’s microphone and compositional strategies we can be witnesses of the kinds of active listening he or she performed while roaming the city.

And indeed, the city is full of expected and unexpected sounds, sounds that consciously and unconsciously influence the way we move and act. Jan Konings stressed the productivity of adding sounds to sonic environments. By implementing sonic signals, human behavior can be manipulated.[5]

This was corroborated by Kees Went, who explained that urban sound design is becoming more and more relevant for city planners. Went also discussed his work on computational models of acoustic ecologies, models through which sounds in public spaces can be simulated. This is useful not only for city planners, but for game designers as well. For this allows them to design incredibly lifelike sonic environments for their games.

Went furthermore asserted that the level of sounds is not as important, in terms of affect, as the meaning of sounds. Changing the sound of a certain event or space will, most probably, change their meaning too. Sonic meaning is created by the interplay of sound source and listener, and as long as listeners have positive associations related to a particular sound, its sound level is less relevant. This is an important principle that urban sound designers need to take into account. Paul de Vos also did not define noise and sound pollution in terms of volume. De Vos suggested that noise should be defined as unwanted sound, thus making its definition highly subjective. This makes it rather complicated to come up with legislation in order to regulate sound and noise. Therefore, De Vos asserted, it makes far more sense to regulate the quality of the sounds that surround us rather than the sound level. This regulation should be done by intensifying awareness, by making people more aware of the sonic environments in which they live.[6]

As Stella van Voorst van Beest’s documentary on the sounds of Holland – is there a typical Dutch soundscape? she asks - shows, however, tranquility is becoming more and more scarce.

Interestingly, it is through the filmed images of sound walls, crowded and deserted places, etc. that the scarcity of silence becomes apparent. Through the visual means she employs, we become aware of sonic phenomena (although in the documentary many interesting and thought-provoking sounds can be heard as well). Like De Vos, she stressed the active input of the inhabitants of a sonic environment: next to the noun “soundscape”, we can add the verb “sound-scaping”.

Van Voorst van Beest’s documentary shows that attempts to gain knowledge or insights into sound does not exclusively need to be achieved via acoustical means. Raviv Ganchrow, for his part, argued that epistemologies of sound are related to ontologies of space - a theme touched upon in his art and writings. He stressed the fact that listening is always relative and contextually biased. Furthermore, non-sonic aspects codetermine our listening. Listening subjects, he asserted, are constructed through shifting relations between self and environment, between sonic and non-sonic domains.[7]

Sound can also establish a relation between invisible spaces and the perceiving subject. Martin Verweij, working on medical acoustical imaging, explained how sonic reverberations – more precisely: ultrasonic echoes – can make invisible spaces visible. Pitches that are present in these echoes are visualized in order to create images of the motion of human organs. In other words, visual information is created out of sounds, enabling the perceiving subject to see what in fact is invisible: our internal bodily space. This is a space that we can hear from the outside: a beating heart, breathing lungs, bowel movements, but which remains invisible to the bare human eye. Sonic reverberation, however, eliminates the physical barriers and opens up this space for visual observation.

Conclusion

In 2003 Jonathan Sterne, Professor in the Department of Art History and Communication Studies at McGill University, Montreal, published The Audible Past. In this book Sterne claims that there is a tremendous amount of research being done on sound. However, this research is primarily taking place in the margins, for the most part not clustered or institutionally structured. What might be needed, Sterne suggests, is a platform where people can exchange ideas about sound, meet one another (virtually), discuss sound, and develop new ideas and theories. In 2011 the Journal of Sonic Studies was set up to provide scholars and artists with such a virtual platform. On December 7, 2012 the SONIC editors gave shape to Sterne’s suggestions by organizing this transdisciplinary expert meeting.

But what about the barriers between the disciplines discussed above? Were these breached as well? Do we want them to be breached? Should sonic studies be transformed into a new, unified discipline? Or is it better to preserve misunderstanding, misunderstanding that can, in turn, be transformed into productive new questions? Judging by the results of the expert meeting, we would opt for the latter and let sonic studies remain transdisciplinary, with disciplines reverbing disruptively within other disciplines, just as sound itself is capable of.

Epiloque: Listening

An expert meeting on sound and sound studies. Talking sounds. Talking in favor of, but also at the expense of. Talking sounds are also silencing sounds. Sounds that monopolize our attention, causing willful negation of other sounds also present during this meeting. Sounds from outside the building in which the meeting took place: snowy sounds … sounds of devices which made the registration of the meeting possible … human sounds: voices of course, but so many others too, such as hitting, rubbing, or compressing various surfaces … And what about the sonic architecture of the conference room? What about the sonic atmosphere of that particular space? Remarkably, many of the recordings have failed because the creaking floor appeared to be louder than the voices of the speakers. As if the potential sounds that somehow already inhabited the room were claiming their own space …

The last words are therefore reserved for the “sounds themselves”. Raviv Ganchrow and Justin Bennett not only talked about sounds but also made sounds talk to the participants. And of course their performances were not (only) meant to serve as a pleasant musical intermezzo. By using sounds which surround us daily, they enabled those present to listen to these daily sounds differently, possibly influencing ideas about sound design, sonic architecture, noise abatement, memory, communication, emotion, impairment, space, etc. Therefore, these sounds not only marked the end of the expert meeting but also announced the urgency to continue the exchange of ideas, theories, concepts, experiences, and affects among artists, policy makers, professionals, and scholars from various disciplines … TBC …

The expert meeting Auditory Culture has been supported financially by the Koninklijke Vereniging voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis (Royal Society for Dutch Music History), the Leids Universiteits Fonds (Leiden University Fund), and the Academie der Kunsten (Academy of Creative and Performing Arts).