I walked nearly to Westbeth, the artist housing complex and formerly the site of the Cunningham Studio, to get to Joseph Lennon's tiny apartment in the West Village. I had met Joseph once before, during a reconstruction of Doubles led by original cast member Patricia Lent (who now serves the

Joseph talked to us after our performance of Doubles, though the specifics of what he said I’ve forgotten. But I learned that he had a dance career before and after his time with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. I learned that he and his husband Dennis O’Connor, another former MCDC member, now split their time between their house upstate and their apartment in the West Village. There was something in his quiet, poetic, but still joyful in Joseph’s presence that I was drawn to.

Some of the original cast came in to coach us individually, Joseph among them. He is now a big man, with a greying beard, and has a quiet presence despite his size. He somehow seemed familiar to me. Maybe his presence was big because his absence was pointed to in this reconstruction, this man who we talked so much about but whose likeness we never saw.

Merce Cunningham Trust as the Director of Licensing. Doubles is a dance that premiered in 1984 and simple concept for Cunningham. The title says it all, really. The piece becomes in some way a self-reflective quest about how to make a dance, and what containers hold a dance: the dancers, the choreographer, the steps themselves, or some concept of this particular dance? As usual, Merce gives no final answer, only proposes something to be experienced and watched. No double-meaning here.

In the reconstruction I did of Doubles in 2015, I learned a part originally danced by Robert Swinston, while my double in the other cast Ernesto Breton learned the "same" part danced originally danced by Rob Remley. Doubles doubled.

Back to Joseph Lennon's West Village apartment on the morning of January 7th, 2018: I walked up four or five flights of narrow stairs, squeezed through the tight hallway, and came to the tiny living room. He invited me into his kitchen. The place hadn't been renovated, and this wave of nostalgia for 1980s New York life hit me, again. Is it nostalgia if I wasn't ever there?

We sat down. He had printed out the quote I'd sent him when I asked by email to interview him: “The most essential thing in dance discipline is devotion, the steadfast and willing devotion to the labor that makes the classwork not a gymnastic hour and a half, or at the lowest level, a daily drudgery, but a devotion that allows the classroom discipline to be moments of dancing too.” This quote was the starting point for the many facets of my inquiry, and also my way in to talk to various alumni of MCDC.

Some flights of fantasy: Was I seeing some version of myself in the future? Or what I might have been like had I been born a few decades earlier? But really what I was asking myself was How could I cultivate the life that he had led and continues to lead?

All the other parts were doubled this way, including the Joseph Lennon/Alan Goode part(s). In this particular reconstruction, we looked at the 1984 rehearsal video as the basis for the material. When this video was filmed, Joseph had broken his foot, so his double Alan Goode danced in both casts. Joseph's version of his solo in Doubles is

lost, at least to the archive.

"After reading what you wrote I stood in my living room, closed my eyes and tried to imagine myself at Merce’s studio. It’s been more

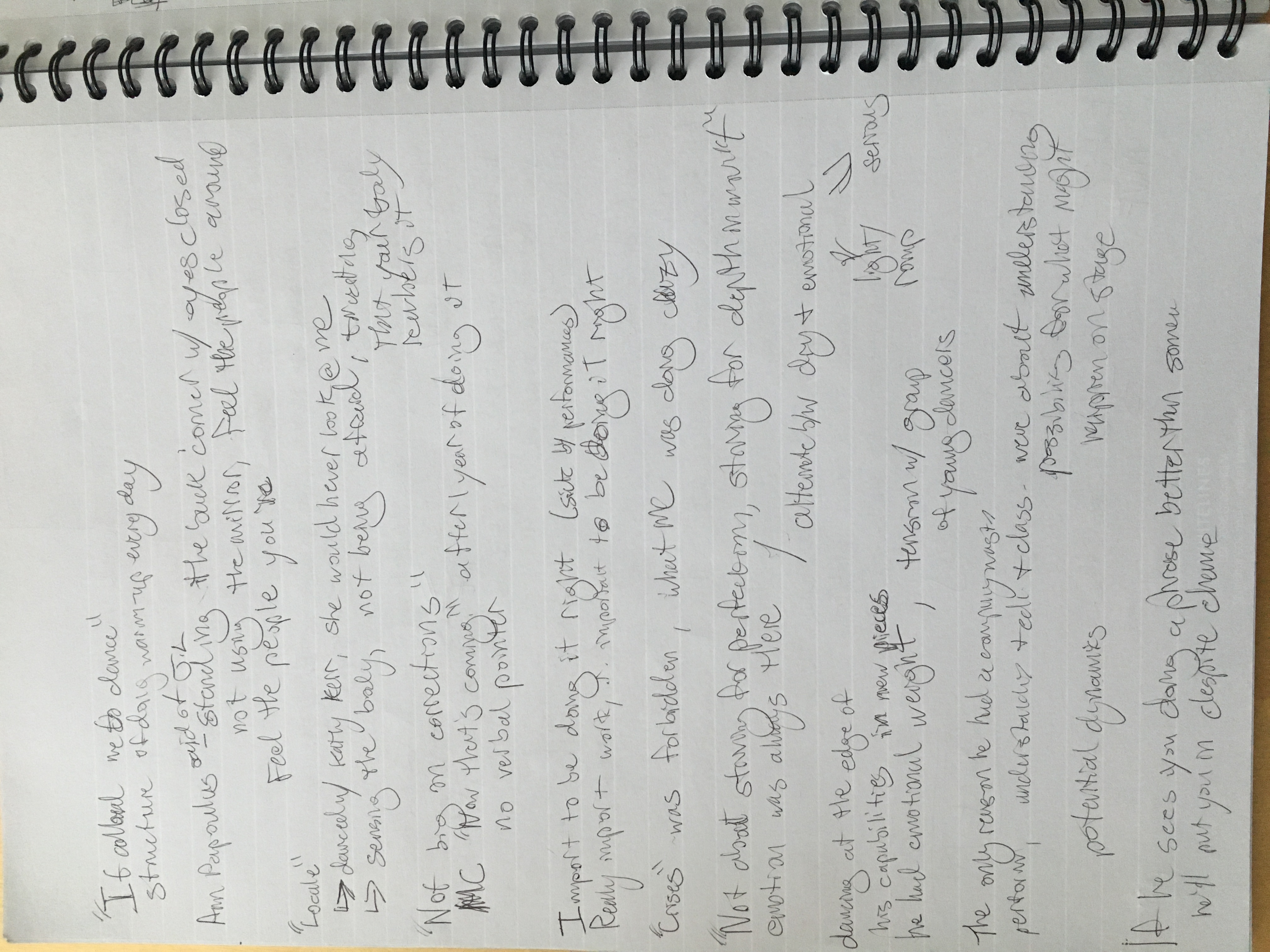

Joseph recalled that in class he would stand in the back corner with his eyes closed, without using the mirror, feeling the people around him. Closing my eyes while taking class has been a method

I’ve used in my own exploration of this technique. Months after this interview, I wrote to Joseph and sent him a draft of this essay. He wrote back detailed description:

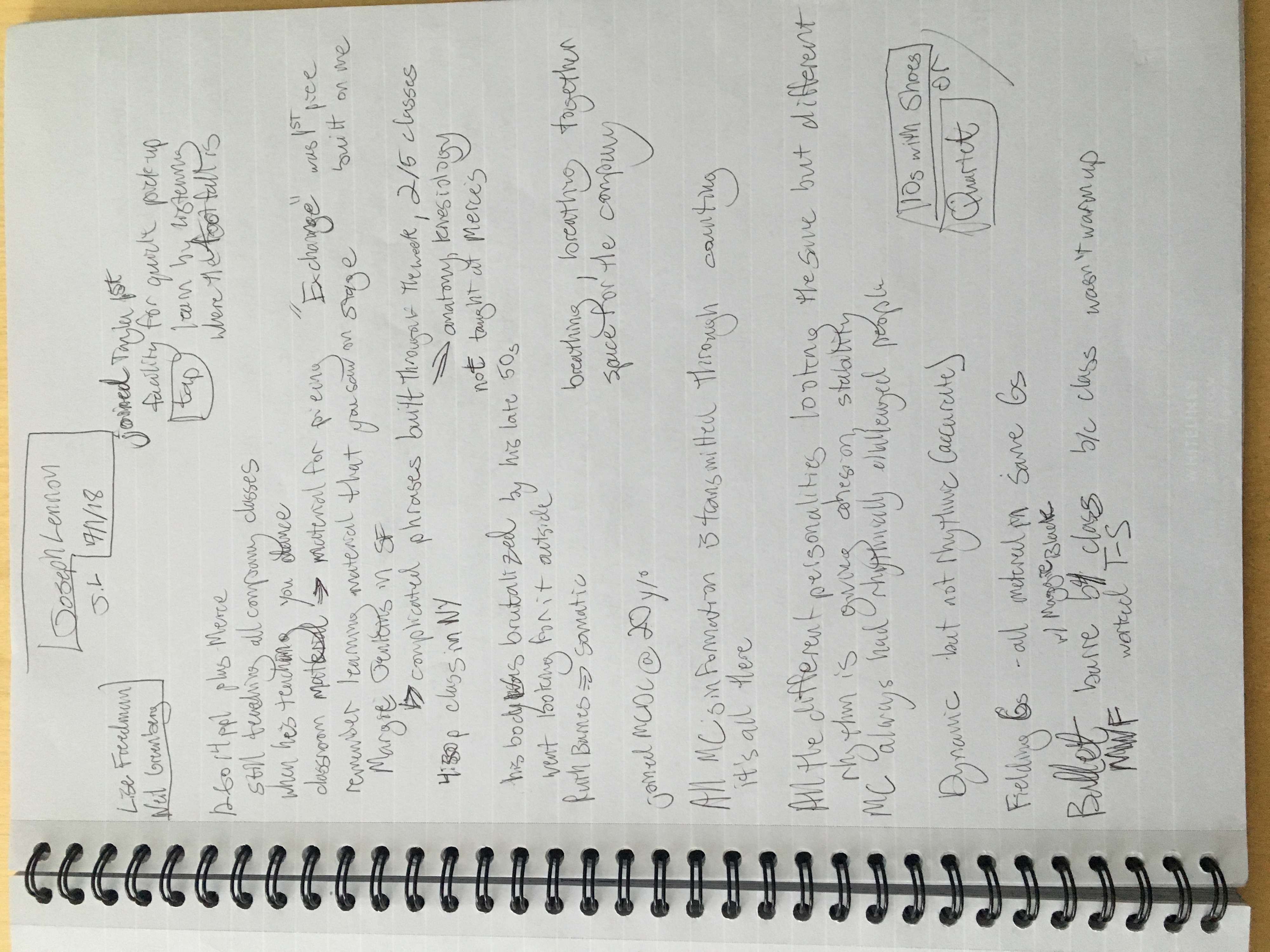

We went on to talk about the quote, and about his life in the Cunningham company. He joined when he was 20 years old, in 1978, after a brief stint dancing with Twyla Tharp. From our conversation, I gathered that dancing for Merce was a very serious pursuit for him: “It was very important work, and it was very important to be doing it right.” In 1978 Merce was still teaching daily company class when Joseph was in the company, and Merce was still performing in pieces. In Joseph’s estimation, the Cunningham company was merely the vehicle which allowed Merce to keep performing.

“How can I use this to get to a better spot?” was a statement of Joseph’s I wrote down. I’m not sure if he was talking about improving his position in the eyes of Merce or about how to use class to get deeper access to his body’s capabilities.

Class and choreography, the two seemed linked in his mind; Joseph saw that for Merce class was about understanding possibilities for what might happen onstage. And not just the steps, but who might perform those steps. “When he’s teaching, you dance.” There was the stereotyped jockeying for Merce’s favor and featured roles within the company. One of the goals

remembered the way I used to embrace the space. Not just sending the energy out but creating an immense circle that enveloped the energy of the room and the space beyond. It gave me a really strong vertical and shifted the weight over my whole foot."

Class, as he described it to me, seemed it was as much an anatomical and experiential practice as a performance preparation and political sphere. Some of the questions Joseph would ask himself, with his eyes closed during class were what he called diagnostics of the body: “What am I feeling today? Where am I?” as well as trying to sense those around him.

When Merce saw “you doing a phrase better than someone else, he’ll put you in" despite, whatever chance operations dictated.

Certainly the repetition in class, the predictability of the form, allowed him the security to experiment this way. If I had to venture, I’d say that Joseph’s unorthodox approach to class helped him stand out. He was certainly a star in Merce’s eye, for the sizable parts he gave to someone so young and new to the company. Merce also seemed to give lots of space by being withholding of direct criticism and compliment. “Now that’s coming,” Merce said to Joseph, the first feedback he’d given him in after years of dancing a part in Locale.

He made the choice to leave because he didn’t want to end up old and bitter there, replaced by a young, eager, curious man who caught Merce’s eye. His eventual replacement was Joseph’s now-husband, Dennis O’Connor. Dennis caught someone else’s eye as well. And the joy went both ways “Your parts are always the most fun to dance,” Dennis said of Joseph’s roles. “There’s something of me in them,” Joseph told me. I think this is true of anyone who danced for Merce, especially those who could pull Merce out of his chance operated plans for a choreography. “I made a mark on the company,” Joseph said, not bragging but delivering fact. From my brief time with him, his quiet confidence, and clarity of thought draws me in to listen and understand, and try to decipher that mark.

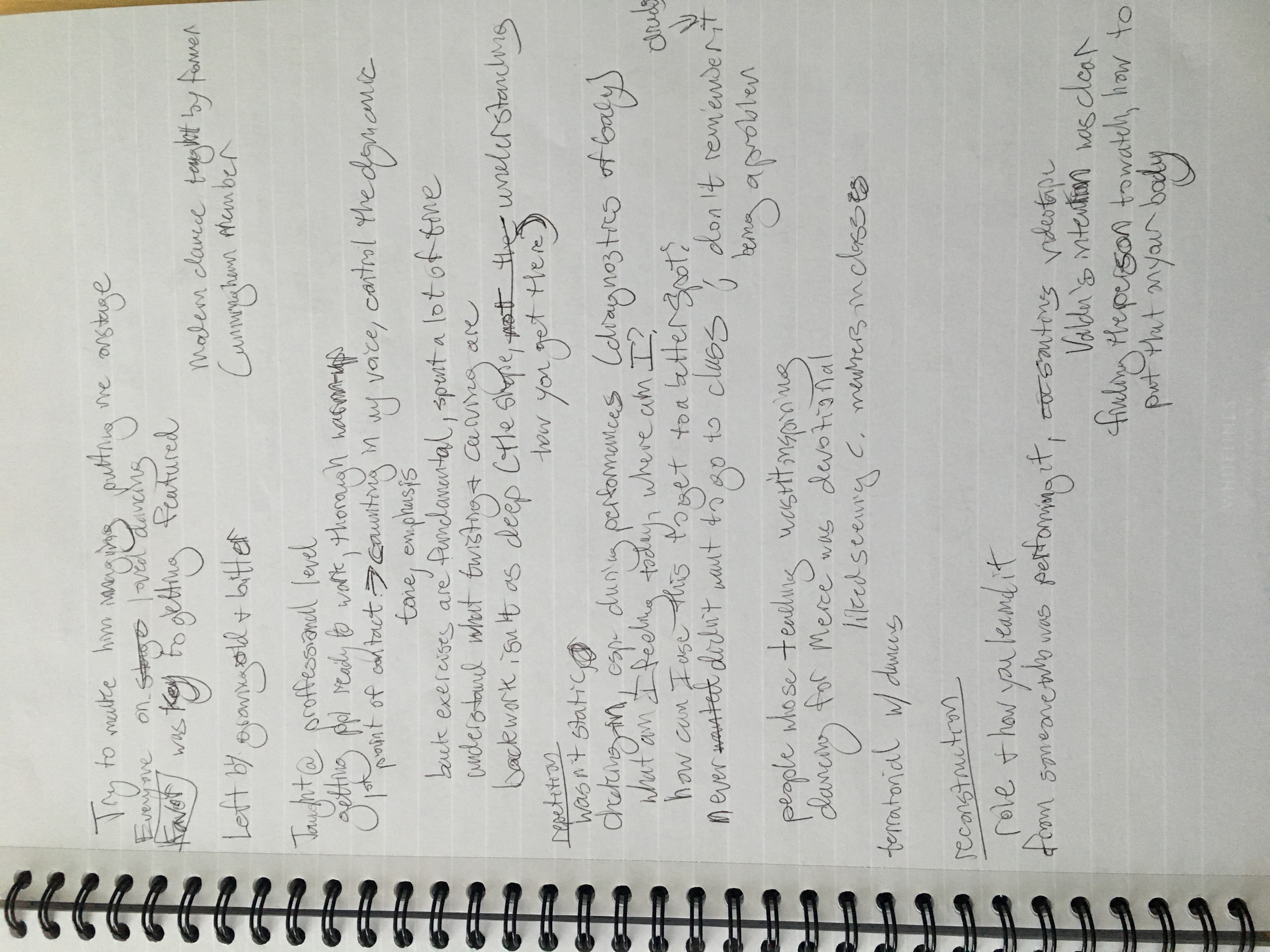

assigned. I remember watching videos of myself dancing in Robert Swinston’s part, and realizing that I’d seen my bobbing head in videos of his. I don’t remember actively trying to imitate his mannerisms (or bad habits) but his energy leapt from the screen to my body. Even in the 80s, with poor quality videotape, this kind of thing happened in learning a person’s steps, Joseph confirmed. He described the work of reconstruction

In replacing dancers in a piece, the company members I’ve worked with have always referred to ‘parts’ rather than ‘roles’ or ‘tracks’, but they do feel like roles

As our time together was winding down, Joseph offered me soup for lunch. I could have stayed and talked with him all afternoon, but I had

Our conversation moved towards reconstruction of dances, and how he saw his work as a dancer differ in originating a part or taking over someone’s part. Joseph confessed that there was often a ‘type’ who a new company member would replace, and learning that person’s part was touchy.